Abstract

Background

The increased incidence of anemia in patients with hiatal hernias (HH) and resolution of anemia after HH repair (HHR) have been clearly demonstrated. However, the implications of preoperative anemia on postoperative outcomes have not been well described. In this study, we aimed to identify the incidence of preoperative anemia in patients undergoing primary HHR at our institution and sought to determine whether preoperative anemia had an impact on postoperative outcomes.

Methods

Using our IRB-approved institutional HH database, we retrospectively identified patients undergoing primary HHR between January 2011 and April 2017 at our institution. We identified patients with anemia, defined as serum hemoglobin levels less than 13 mg/dL in men and 12 mg/dL in women, measured within two weeks prior to surgery, and compared this group to a cohort of patients with normal preoperative hemoglobin. Perioperative outcomes analyzed included estimated blood loss (EBL), operative time, perioperative blood transfusions, failed postoperative extubation, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, postoperative complications, length of stay (LOS), and 30-day readmission. Outcomes were compared by univariable and multivariable analyses, with significance set at p < 0.05.

Results

We identified 263 patients undergoing HHR. The median age was 66 years and most patients were female (78%, n = 206). Seventy patients (27%) were anemic. In unadjusted analyses, anemia was significantly associated with failed postoperative extubation (7 vs. 2%, p = 0.03), ICU admission (13 vs. 5%, p = 0.03), postoperative blood transfusions (9 vs. 0%, p < 0.01), and postoperative complications (41 vs. 18%, p < 0.01). On adjusted multivariable analysis, anemia was associated with 2.6-fold greater odds of postoperative complications (OR 2.57; 95% CI 1.36–4.86; p < 0.01).

Conclusions

In this study, anemia had a prevalence of 27% in patients undergoing primary HHR. Anemic patients had 2.6-fold greater odds of developing postoperative complications. Anemia is common in patients undergoing primary HHR and warrants consideration for treatment prior to elective repair.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Hiatal hernias (HH) are being diagnosed with increasing frequency and have an estimated prevalence of 0.8–2.9% in patients undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) [1]. The indications for surgical repair have changed in recent years, with surgery now reserved for symptomatic hernias [2]. Although most patients with HH are asymptomatic, patients referred for repair generally present with symptoms related to reflux, gastrointestinal obstruction, or gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) [3, 4]. GIB in the setting of HH can be acute or chronic, is often occult, and can lead to significant iron-deficiency anemia [5,6,7]. In patients with HH, GIB has been attributed to the presence of Cameron lesions (CL), which are linear erosions or ulcerations resulting from friction of opposing mucosal surfaces at the level of the diaphragm in the setting of HH [8]. Today, a significant number of patients are referred for hiatal hernia repair (HHR) specifically as treatment of their anemia [2].

Since the identification of CL, resolution of anemia after HHR has been demonstrated in numerous studies [3, 9,10,11,12], particularly in large hernias [10, 13]. However, despite a reported incidence of preoperative anemia ranging from 15% to as high as 45% in patients with HH [3, 9, 10, 12, 14], the implications of anemia on surgical outcomes following HHR have not been evaluated in the literature. In this study, we aimed to determine the incidence of preoperative anemia in all patients undergoing primary HHR at our institution and to determine whether preoperative anemia was associated with poorer perioperative outcomes.

Materials and methods

Patient selection and preoperative workup

Utilizing our IRB-approved institutional hiatal hernia database, we retrospectively identified all patients undergoing HHR at our institution between January 2011 and April 2017. Preoperative evaluation included a full history and physical examination, as well as a chest X-ray, EGD, esophageal manometry, 24-h PH study, and routine bloodwork including a complete blood count (CBC).

Hernia repair

All hiatal hernia repairs were performed by one of the four surgeons (MP, KC, ER, and FP) and surgical approach was defined as minimally invasive surgery (MIS) if performed laparoscopically or with robotic assistance. Hernia size was defined according to the intraoperative measurement of the antero-posterior diameter of the diaphragmatic defect as small if less than 3 cm, moderate if 3.0–4.9 cm, large if 5 cm or greater with less than 50% gastric herniation, and giant if 5 cm or greater with over 50% gastric herniation. With respect to operative technique, all patients underwent general anesthesia and all repairs were started in minimally invasive fashion, with conversion to an open procedure performed as deemed necessary at the time of repair. The surgical procedure always included excision of the hernia sac, reduction of the hernia with at least 3 cm of distal esophagus into the abdomen, crural closure with interrupted non-absorbable suture, and partial or total fundoplication. Most patients also had synthetic absorbable mesh reinforcement at the time of cruroplasty as deemed necessary by the operating surgeon.

Data collection

When available, preoperative EGD records were reviewed for completeness and identification of Cameron lesions, which were defined as either linear erosions or ulcers present at or near the level of the diaphragmatic hiatus. Baseline characteristics collected during chart review included age, sex, Body Mass Index (BMI), Charlson Comorbidity Indices (CCI) [15, 16], hernia type, hernia size, surgical approach, and urgency of repair (emergent vs. elective).

Study design and evaluated outcomes

We identified all patients with preoperative anemia, defined according to the World Health Organization (WHO) as serum hemoglobin (Hgb) levels less than 13 mg/dL in men and less than 12 mg/dL in women [17], measured within 2 weeks prior to surgery. We excluded patients who did not have preoperative bloodwork available for determination of anemia status and patients with recurrent hiatal hernias. Perioperative outcomes were then compared between anemic and non-anemic patients, focusing on estimated blood loss (EBL), operative times, need for blood transfusion, failure to extubate postoperatively, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, postoperative complications, length of stay (LOS), and 30-day readmission. Postoperative complications were graded in severity using the modified Clavien–Dindo (CD) Scale [18].

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics and unadjusted associations between groups were performed using χ2 tests for categorical variables and exact χ2 tests for variables with an incidence of 5 or less. Student’s t tests were used to compare normally distributed numerical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were utilized for non-normally distributed numerical variables. Multiple regression or logistic regression analyses were used to estimate the associations of preoperative anemia with postoperative outcomes adjusted for potential confounding variables, including CCI, urgency of repair (elective vs. emergent), and presence of CL on EGD. All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and all statistical hypothesis tests were evaluated at the 0.05 significance level.

Results

Demographic and preoperative characteristics

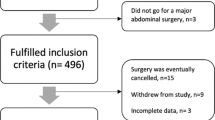

Two hundred and seventy-six patients underwent hiatal hernia repair during the study period. Thirteen patients were excluded (6 for reoperation and 7 for missing lab work), leaving 263 patients to be included in this study. Of these, 70 patients (27%) were found to be anemic and 193 patients (73%) did not demonstrate anemia on preoperative bloodwork. The median age of the entire study population was 66 years, with 143 patients (54%) being 65 years of age or older. Of these elderly patients, 42 (29%) were anemic. Two hundred and six patients were female (78%), of whom 26% were anemic; 57 patients were male (22%), of whom 30% were anemic. Of the 184 women aged 50 years or older, 27% were anemic as compared to only 18% of the 22 women aged 49 years or younger (data not shown).

The average BMI was 30 kg/m2 (± 6), and the average CCI was 3.1 (± 1.9) for the entire study population. A total of 67 patients (30%) demonstrated CL on EGD. Thirty patients (11%) had Type I HH, 7 (3%) had Type II HH, 206 (78%) had Type III HH, and 20 (8%) had Type IV HH. With respect to hernia size, 21 patients (8%) had small hernias, 48 (18%) had moderate, 157 (60%) had large, and 37 (14%) had giant HH. Twenty-one patients (8%) underwent emergent repair and 11 patients (4%) underwent conversion to open repair, with the remaining 252 patients (96%) undergoing minimally invasive repair.

Demographic and preoperative characteristics for each group are summarized in Table 1. Patients were similar with respect to age, gender, BMI, hernia types and sizes, and surgical approach. However, anemic patients had a significantly higher mean CCI of 3.7 (± 2.3) as compared to only 2.9 (± 1.7) in non-anemic patients (p < 0.01). In the anemic group, 43% of patients had evidence of CL compared to only 25% of non-anemic patients (p < 0.01). The anemic group also had a significantly higher incidence of emergent repair, with 10 patients (14%) undergoing emergent surgery compared to 11 patients (6%) in the non-anemic group (p = 0.02).

Perioperative outcomes

Comparisons of perioperative outcomes according to anemia status for all 263 patients are summarized in Table 2. Median EBL for all 263 patients was 20 ml and median operative time was 240 min, with neither outcome differing significantly between groups. Only two patients required intraoperative blood transfusions, and both were anemic preoperatively. Five anemic patients (7%) failed to extubate successfully and remained intubated postoperatively compared to only three patients (2%) in the non-anemic group (p = 0.03). Similarly, nine anemic patients (13%) required ICU admission during their hospitalization compared to ten non-anemic patients (5%) requiring ICU admission (p = 0.03). Six total patients required postoperative blood transfusions, and all six were anemic at baseline (p < 0.01). Sixty-four total patients (24%) developed complications postoperatively, with 41% of anemic patients (n = 29) developing one or more complication compared to only 18% (n = 35) in the non-anemic group (p < 0.01). When graded on the modified CD scale, the majority of all complications (84%) were either grade I or II, and there was no significant difference in the severity of complications according to anemia status, as demonstrated in Table 2 (p = 0.50). Of note, there was no mortality in either group. Although patients in the anemia group had a longer median LOS of 3 days, as compared to only 2 days in the non-anemic group, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.08). Finally, both groups had the same 30-day readmission rate of 9%.

In multivariable logistic regression analysis, anemia was associated with significantly higher odds of developing any complication (OR 2.57; 95% CI 1.36–4.86; p < 0.01). The presence of preoperative anemia was not associated with any significant difference in operative time, EBL, LOS, or 30-day readmission rate, as shown in Table 3. Due to the limited number of outcomes, we were unable to assess the association of anemia with failure to extubate postoperatively, ICU admission, or perioperative blood transfusion by multivariable analysis.

Anemia severity and overall complications

Of the 70 anemic patients in this study, 9% had preoperative Hgb levels of 7.0–9.0 mg/dL, 10% had Hgb levels of 9.1–10.0 mg/dL, 21% had Hgb levels of 10.1–11.0, 44% had Hgb levels of 11.1–12.0, and 16% had Hgb levels of 12.1–13.0 (Table 4). There was no significant difference in the incidence of overall complications according to Hgb level (p = 0.57).

Discussion

The majority of patients with hiatal hernias are asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic from their disease. However, when symptomatic, most patients present with varying degrees of reflux, obstruction, or gastrointestinal bleeding depending on the type of hernia present. Type I hernias account for about 90–95% of all hiatal hernias and generally present with symptoms of reflux. Hernia types II, III, and IV account for the remaining 5–10% of all hiatal hernias and are collectively referred to as paraesophageal hernias (PEH) [19]. These hernias generally present with symptoms related to gastric and other intra-abdominal organ migration into the chest, including obstruction, postprandial fullness, chest pain, and shortness of breath [2]. Although less common, GIB is another relatively frequent presentation in patients referred for HHR. GIB can present as acute, chronic, or occult bleeding [5], and has long been the suspected cause of iron-deficiency anemia in patients with HH [6, 20].

The likely culprit lesion responsible for blood loss in patient with HH is referred to as the Cameron lesion. CL is a collective term used to refer to both erosions and more severe ulcerations detected endoscopically within the stomach at or near the level of the diaphragmatic hiatus in patients with HH. Cameron lesions are classically thought to result from mechanical trauma due to friction of opposing gastric surfaces at the level of the diaphragmatic hiatus with respiration [8, 12]. However, mucosal ischemia due to extrinsic pressure from the diaphragm and acid-related mucosal injury have also been implicated [5, 21,22,23,24]. Resolution of CL and anemia after HHR have been well established [3, 9,10,11,12], but the implications of preoperative anemia on perioperative outcomes of HHR have not been characterized in the literature. In this study, we aimed to first evaluate the incidence of preoperative anemia in patients undergoing primary HHR at our institution. Secondly, we sought to determine whether preoperative anemia was associated with poorer perioperative outcomes in patients undergoing HHR.

Incidence of anemia in patients undergoing HHR

In our study population, 27% of patients were anemic preoperatively. This number is consistent with previously reported incidences of 15–45% anemia in patients undergoing HHR [3, 9, 10, 12, 14]. While many studies have focused on the association of anemia with PEH (Types II–IV), this study demonstrates that preoperative anemia is also a common finding in patients with Type I hernias, with 11% of anemic patients having Type I hernias in this study. Similarly, although commonly associated with larger hernias [21, 22, 25], this study demonstrates that preoperative anemia is prevalent across all hernia sizes, as 26% of anemic patients had either small or moderate-size hernias.

Incidence of Cameron lesions in patients undergoing HHR

The incidence of Cameron lesions in patients with HH has been estimated in recent studies to range from 10 to 32% [10, 26]. Our findings of 30% incidence of CL in patients undergoing HHR appear consistent with prior reports. In our study, patients with anemia had over 1.5 times the incidence of CL (41%) on EGD as patients who were not anemic preoperatively (25%). These findings are consistent with Cameron and Higgins’s reported CL incidences of 41 and 24% in patients with and without evidence of anemia, respectively [8], and support the long-established association between Cameron lesions and anemia in patients with HH.

The fact that only 41% of anemic patients had demonstrable CL on preoperative EGD warrants further discussion. Potential explanations for these findings include the notion that these lesions are often missed on initial endoscopy, especially if endoscopists are not actively searching for them [26, 27]. Additionally, Cameron lesions have been thought to heal and recur over time [3, 8] and to develop in variable locations as the mechanical forces applied to the gastric mucosa can shift over time with changes in gastric and hernia positions [22]. This resulting fluidity in the presence and location of CL makes them a significant diagnostic challenge.

Anemia and postoperative outcomes

With respect to the implications of anemia on perioperative outcomes of patients undergoing HHR, we demonstrated that by univariable analysis, patients with preoperative anemia had significantly increased rates of failed postoperative extubation, postoperative ICU admissions, postoperative blood transfusions, and overall complications following HHR. However, at baseline, anemic patients in our study had a significantly higher comorbidity burden and were more likely to have presented for emergent repair, both factors associated with poorer postoperative outcomes [19, 28,29,30]. Interestingly, despite a significantly increased rate of overall complications in anemic patients, there was no significant difference in the severity of these complications or in the rate of 30-day readmission between groups. Although anemic patients appeared to have a longer median LOS by 1 day, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p < 0.08) on univariable analysis.

On multivariable analysis accounting for baseline differences between groups including CCI, urgency of repair (elective vs. emergent), and presence of CL on EGD, we found that anemic patients still had 2.6 times greater odds of developing any complication following HHR (p < 0.01). Anemia was not significantly associated with EBL, operative time, LOS, or 30-day readmission. Unfortunately, there were insufficient incidences of failed postoperative extubation, ICU admission, and need for blood transfusion to conduct adjusted analyses on these outcomes, and the implications of anemia on these specific outcomes require further investigation in larger studies.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify anemia as a risk factor for complications specifically in patients undergoing HHR. Anemia in and of itself is associated with increased postoperative complications and mortality across disciplines [31,32,33,34,35,36]. However, we felt that anemia specifically in patients with HH was deserving of particular attention given the remarkably high prevalence in this patient population. Again, we found an incidence of anemia of 27% in our study. Given an estimated prevalence of 5% anemia in the general population [37], we estimated the prevalence of anemia in patients undergoing HHR to be over five times greater than that of the average population. Because HH is a disease most prevalent in the elderly, one may attribute some of the increased anemia observed to the effects of aging. However, in this study, we found a prevalence of anemia of 29% in elderly patients (65 years or over), which is still three times greater than the estimated prevalence of 10% anemia in this age group in the general population [38]. Similarly, anemia is also prevalent in pre-menopausal women due gynecologic-related etiologies. Given the significantly greater proportion of women in this study, we felt that a gender-specific breakdown was also deserving of mention. We found the prevalence of anemia in women aged 0–49 years to be 18%, which is 1.5 times greater than the 12% estimated by the CDC in this age group [39]. We found that 27% of women aged 50 years or older were anemic in this study, which is three times the 9% prevalence estimated by the CDC [39]. Therefore, we estimate that even when accounting for age and gender, anemia is two to five times more common in patients with HH than in the general population.

Preoperative anemia as a predictor for complications

Again, many risk factors for complications and mortality following HHR have been previously described. Given these known predictors, models such as the one devised by Ballian et al. to predict major morbidity and mortality following repair can be quite useful to the clinician in deciding whether or not to operate on a symptomatic patient [30]. Given the significantly increased prevalence of anemia in patients with HH and its apparent impact on postoperative outcomes, perhaps preoperative anemia should be added as a risk factor to such models.

Given our findings, we believe that consideration for treatment of anemia is likely warranted in the elective setting, with the mode of treatment obviously depending on the degree of anemia observed. In this study, we were unable to detect any significant difference in the incidence of complications in relation to severity of anemia, likely due to the relatively small number of anemic patients included. Certainly, the potential risks associated with blood transfusion should be considered when deciding to treat preoperative anemia. Given that most anemic patients in this study had Hgb levels between 11.1 and 13.0 mg/dL (60%), we believe our results should alert caregivers to explore medical means of optimizing Hgb levels for values that are normally considered acceptable for operative procedures, but appear to result in a higher incidence of complications.

Study limitations

We acknowledge that this study has a number of limitations, the first being its retrospective nature. We believe we were able to partly compensate for this limitation by including a multivariable analysis for perioperative outcomes. Additionally, factors such as the need for perioperative blood transfusion or identification of CL on EGD are subject to some variability on the part of each clinician, reducing the uniformity in our study.

Although this constitutes a relatively large series of HH, we were unable to complete a multivariable analysis of some of the less common postoperative events that appeared to differ between groups based on univariable analysis. Additionally, the lack of follow-up in many patients prevented the analysis of more long-term outcomes including resolution of anemia, quality of life, and recurrence rates, all of which are very much clinically relevant and require further investigation.

Lastly, the definition of anemia varies tremendously in related literature, and although we chose to utilize WHO definitions of anemia for the classification of our study groups, many other definitions have been used, making comparison of our findings to similar studies difficult. Furthermore, the lack of iron-studies available for review prevented the diagnosis of iron-deficiency anemia, limiting our ability to attribute patient anemia specifically to gastrointestinal bleeding and iron-deficiency anemia. It is certainly possible and indeed likely that some of our patients were anemic due to other reasons including the presence of comorbidities. However, we were able to account for differences in comorbidity status between groups on multivariable analysis.

Conclusion

In this study, anemia had a prevalence of 27% in patients undergoing primary HHR. Anemic patients had a 2.6-fold increase in odds of developing complications postoperatively. We therefore conclude that heightened awareness for the presence and the implications of preoperative anemia in patients undergoing HHR is necessary. Furthermore, consideration for treatment of anemia prior to elective repair is likely warranted. Larger prospective studies are needed to validate our findings and to investigate the implications of anemia on rarer and more long-term postoperative outcomes.

References

Johnson DA, Ruffin WK (1996) Hiatal hernia. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 6:641–666

Lebenthal A, Waterford SD, Fisichella PM (2015) Treatment and controversies in paraesophageal hernia repair. Front Surg 2:13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2015.00013

Haurani C, Carlin AM, Hammoud ZT, Velanovich V (2012) Prevalence and resolution of anemia with paraesophageal hernia repair. J Gastrointest Surg 16:1817–1820. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-012-1967-6

Hocking BV, Alp MH, Grant AK (1976) Gastric ulceration within hiatus hernia. Med J Aust 2:207–208

Gupta P, Suryadevara M, Das A, Falterman J (2015) Cameron ulcer causing severe anemia in a patient with diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Case Rep 16:733–736. https://doi.org/10.12659/AJCR.894145

Bock AV, Dulin JW, Brooke PA (1933) Diaphragmatic hernia and secondary anemia; ten cases. N Engl J Med 209:615–625. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM193309282091301

Holt JM, Mayet FG, Warner GT, Callender ST, Gunning AJ (1968) Iron absorption and blood loss in patients with hiatus hernia. Br Med J 3:22–25

Cameron AJ, Higgins JA (1986) Linear gastric erosion: a lesion associated with large diaphragmatic hernia and chronic blood loss anemia. Gastroenterology 91:338–342

Trastek VF, Allen MS, Deschamps C, Pairolero PC, Thompson A (1996) Diaphragmatic hernia and associated anemia: response to surgical treatment. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 112:1340–1344. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5223(96)70149-6 (discussion 1344)

Carrott PW, Markar SR, Hong J, Kuppusamy MK, Koehler RP, Low DE (2013) Iron-deficiency anemia is a common presenting issue with giant paraesophageal hernia and resolves following repair. J Gastrointest Surg 17:858–862. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-013-2184-7

Skipworth RJE, Staerkle RF, Leibman S, Smith GS (2014) Transfusion-dependent anaemia: an overlooked complication of paraoesophageal hernias. Int Sch Res Notices 2014:479240. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/479240

Windsor CW, Collis JL (1967) Anaemia and hiatus hernia: experience in 450 patients. Thorax 22:73–78

Cameron AJ (1976) Incidence of iron deficiency anemia in patients with large diaphragmatic hernia: a controlled study. Mayo Clin Proc 51:767–769

Carrott PW, Hong J, Kuppusamy M, Koehler RP, Low DE (2012) Clinical ramifications of giant paraesophageal hernias are underappreciated: making the case for routine surgical repair. Ann Thorac Surg 94:421–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.04.058 (discussion 426)

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J (1994) Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 47:1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5

World Health Organization (2011) Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity: VMNIS

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien P-A (2004) Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 240:205–213

Sihvo EI, Salo JA, Räsänen JV, Rantanen TK (2009) Fatal complications of adult paraesophageal hernia: a population-based study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 137:419–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.05.042

Segal HL (1931) Secondary anemia associated with diaphragmatic hernia. NY State J Med 31:692

Weston AP (1996) Hiatal hernia with cameron ulcers and erosions. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 6:671–679

Gray DM, Kushnir V, Kalra G, Rosenstock A, Alsakka MA, Patel A, Sayuk G, Gyawali CP (2015) Cameron lesions in patients with hiatal hernias: prevalence, presentation, and treatment outcome. Dis Esophagus 28:448–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/dote.12223

Moskovitz M, Fadden R, Min T, Jansma D, Gavaler J (1992) Large hiatal hernias, anemia, and linear gastric erosion: studies of etiology and medical therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 87:622–626

Panzuto F, Di Giulio E, Capurso G, Baccini F, D’Ambra G, Delle Fave G, Annibale B (2004) Large hiatal hernia in patients with iron deficiency anaemia: a prospective study on prevalence and treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 19:663–670. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01894.x

Nguyen N, Tam W, Kimber R, Roberts-Thomson IC (2002) Gastrointestinal: Cameron’s erosions. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 17:343

Maganty K, Smith RL (2008) Cameron lesions: unusual cause of gastrointestinal bleeding and anemia. Digestion 77:214–217. https://doi.org/10.1159/000144281

Chun CL, Conti CA, Triadafilopoulos G (2011) Cameron ulcers: you will find only what you seek. Dig Dis Sci 56:3450–3452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-011-1803-y

Polomsky M, Hu R, Sepesi B, O’Connor M, Qui X, Raymond DP, Litle VR, Jones CE, Watson TJ, Peters JH (2010) A population-based analysis of emergent vs. elective hospital admissions for an intrathoracic stomach. Surg Endosc 24:1250–1255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-009-0755-1

Stylopoulos N, Gazelle GS, Rattner DW (2002) Paraesophageal hernias: operation or observation? Ann Surg 236:492–500. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.SLA.0000029000.06861.17 (discussion 500)

Ballian N, Luketich JD, Levy RM, Awais O, Winger D, Weksler B, Landreneau RJ, Nason KS (2013) A clinical prediction rule for perioperative mortality and major morbidity after laparoscopic giant paraesophageal hernia repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 145:721–729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.12.026

Wu W-C, Schifftner TL, Henderson WG, Eaton CB, Poses RM, Uttley G, Sharma SC, Vezeridis M, Khuri SF, Friedmann PD (2007) Preoperative hematocrit levels and postoperative outcomes in older patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA 297:2481–2488. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.22.2481

Gupta PK, Sundaram A, Mactaggart JN, Johanning JM, Gupta H, Fang X, Forse RA, Balters M, Longo GM, Sugimoto JT, Lynch TG, Pipinos II (2013) Preoperative anemia is an independent predictor of postoperative mortality and adverse cardiac events in elderly patients undergoing elective vascular operations. Ann Surg 258:1096–1102. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e318288e957

Muñoz M, Gómez-Ramírez S, Campos A, Ruiz J, Liumbruno GM (2015) Pre-operative anaemia: prevalence, consequences and approaches to management. Blood Transfus 13:370–379. https://doi.org/10.2450/2015.0014-15

Partridge J, Harari D, Gossage J, Dhesi J (2013) Anaemia in the older surgical patient: a review of prevalence, causes, implications and management. J R Soc Med 106:269–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076813479580

Musallam KM, Tamim HM, Richards T, Spahn DR, Rosendaal FR, Habbal A, Khreiss M, Dahdaleh FS, Khavandi K, Sfeir PM, Soweid A, Hoballah JJ, Taher AT, Jamali FR (2011) Preoperative anaemia and postoperative outcomes in non-cardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 378:1396–1407. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61381-0

Bodewes TCF, Pothof AB, Darling JD, Deery SE, Jones DW, Soden PA, Moll FL, Schermerhorn ML (2017) Preoperative anemia associated with adverse outcomes after infrainguinal bypass surgery in patients with chronic limb-threatening ischemia. J Vasc Surg 66:1775–1785.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2017.05.103

Beutler E, Waalen J (2006) The definition of anemia: what is the lower limit of normal of the blood hemoglobin concentration? Blood 107:1747–1750. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2005-07-3046

Patel KV (2008) Epidemiology of anemia in older adults. Semin Hematol 45:210–217. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminhematol.2008.06.006

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2002) Iron deficiency–United States, 1999–2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 51:897–899

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Drs. Chevrollier, Brown, Keith, Pucci, Chojnacki, Rosato, and Palazzo, as well as Ms. Szewczyk, have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chevrollier, G.S., Brown, A.M., Keith, S.W. et al. Preoperative anemia: a common finding that predicts worse outcomes in patients undergoing primary hiatal hernia repair. Surg Endosc 33, 535–542 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6328-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6328-4