Abstract

Background

Nearly 20% of patients who undergo hiatal hernia (HH) repair and anti-reflux surgery (ARS) report recurrent HH at long-term follow-up and may be candidates for redo surgery. Current literature on redo-ARS has limitations due to small sample sizes or single center experiences. This type of redo surgery is challenging due to rare but severe complications. Furthermore, the optimal technique for redo-ARS remains debatable. The purpose of the current multicenter study was to review the outcomes of redo-fundoplication and to identify the best ARS repair technique for recurrent HH and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Methods

Data on 975 consecutive patients undergoing hiatal hernia and GERD repair were retrospectively collected in five European high-volume centers. Patient data included demographics, BMI, techniques of the first and redo surgeries (mesh/type of ARS), perioperative morbidity, perioperative complications, duration of hospitalization, time to recurrence, and follow-up. We analyzed the independent risk factors associated with recurrent symptoms and complications during the last ARS. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism® and R software®.

Results

Seventy-three (7.49%) patients underwent redo-ARS during the last decade; 71 (98%) of the surgeries were performed using a minimally invasive approach. Forty-two (57.5%) had conversion from Nissen to Toupet. In 17 (23.3%) patients, the initial Nissen fundoplication was conserved. The initial Toupet fundoplication was conserved in 9 (12.3%) patients, and 5 (6.9%) had conversion of Toupet to Nissen. Out of the 73 patients, 10 (13%) underwent more than one redo-ARS. At 8.5 (1–107) months of follow-up, patients who underwent reoperation with Toupet ARS were less symptomatic during the postoperative period compared to those who underwent Nissen fundoplication (p = 0.005, OR 0.038). Patients undergoing mesh repair during the redo-fundoplication (21%) were less symptomatic during the postoperative period (p = 0.020, OR 0.010). The overall rate of complications (Clavien-Dindo classification) after redo surgery was 11%. Multivariate analysis showed that the open approach (p = 0.036, OR 1.721), drain placement (p = 0.0388, OR 9.308), recurrence of dysphagia (p = 0.049, OR 8.411), and patient age (p = 0.0619, OR 1.111) were independent risk factors for complications during the last ARS.

Conclusions

Failure of ARS rarely occurs in the hands of experienced surgeons. Redo-ARS is feasible using a minimally invasive approach. According to our study, in terms of recurrence of symptoms, Toupet fundoplication is a superior ARS technique compared to Nissen for redo-fundoplication. Therefore, Toupet fundoplication should be considered in redo interventions for patients who initially underwent ARS with Nissen fundoplication. Furthermore, mesh repair in reoperations has a positive impact on reducing the recurrence of symptoms postoperatively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Fundoplication is one of the most effective treatments for hiatal hernia and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The revolution of minimally invasive surgery and the initial report of laparoscopic fundoplication in 1990 by Dallemagne have led to an increase in the number of fundoplications performed [1,2,3]. Studies have shown that the functional outcomes of laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery (ARS) are nearly equal to those of the open approach with significantly lower rates of postoperative morbidity and shorter hospital stay [4,5,6,7]. However, the ARS, performed by an open approach or laparoscopically, can fail and thus require repeat surgery for persistent or recurrent symptoms [8,9,10,11]. The failure rate of open or laparoscopic approaches ranges from 3 to 30% [7, 10]. This variability may be explained by differences in the definition of failure from center to center. It is clear that, as the surgeon progresses through his/her learning curve, the number of cases of redo-fundoplication decreases [12]. In fact, most laparoscopic fundoplication failures occur at the beginning of the surgeon’s career [13].

The management of cases of reoperation is more complex and most patients are dissatisfied. Operating on these patients is challenging and complex with a high rate of morbidity up to 50% [14]. Reoperation can lead to life-threatening complications such as intraoperative esophageal perforation due to the altered anatomy. Although the effectiveness of mesh in preventing recurrence is reported in the literature, there is no consensus regarding the role of mesh repair in treating recurrent cases [15]. Furthermore, there are limited data in the literature concerning the best fundoplication technique (360°, 270° or 180°) for redo surgery to prevent new onset or recurrence of GERD [16].

This large multicenter study on redo-fundoplication aimed, first, to report specific intra- and postoperative complications and the short-term efficacy and, second, to analyze quality of life according to each type of ARS.

Materials and methods

Data source and study population

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Montpellier approved this study protocol (#17-0124) and waived the requirement for informed consent. We retrospectively reviewed the database of re-operative open and laparoscopic ARS cases performed in five high-volume centers (two at the University Hospital of Montpellier, one at the University Hospital of Nimes, one at the Beau Soleil Polyclinic and one at the Luxembourg Hospital). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each institution. All operations were performed by expert senior surgeons who have performed more than 50 ARS procedures.

Out of 975 patients undergoing surgery for hiatal hernia, GERD or both in the five centers between January 2007 and January 2017, seventy-three (7.49%) patients underwent redo-fundoplication.

Patient data included demographics, BMI, techniques of the first and reoperation surgeries (mesh/type of fundoplication), perioperative morbidity, operative complications, duration of hospitalization, interval to recurrence and follow-up.

Definitions of recurrence and failure

The reasons for redo surgery after a failed fundoplication are as follows: persistent GERD, recurrent GERD, new disabling symptoms such as severe dysphagia, and frequent vomiting.

Currently, there is a lack of a common definition of fundoplication failure. In our own clinical practice, the usual definition of failure requiring reoperation is recurrent or persistent gastroesophageal reflux symptoms developing from an anatomical complication or new disabling symptoms such as dysphagia or frequent vomiting. Preoperative work-up before redo surgery includes endoscopy and barium swallow or a CT scan to assess all possible anatomical complications such as recurrence of hiatal hernia, wrap migration, stenosis, etc [7].

Inclusion criteria

All patients undergoing operation or reoperation for recurrent hiatal hernia and/or GERD from January 2007 to January 2017 in the above five centers were included in the study. All patients underwent the same operative techniques and experiences and postoperative protocols.

Exclusion criteria

-

Pediatric patients less than 16 years old

-

Patients with severe mental disabilities

-

Patients with missing data at follow-up and/or missing operative notes

The primary endpoint for our study was to identify the best redo-ARS procedure in terms of morbidity and efficacy in treating recurrent symptoms (univariate/multivariate analysis of the factors associated with recurrent symptoms after the last ARS).

The secondary endpoints were as follows:

-

A.

to study the factors associated with risks of complications and to define the parameters associated with the worst and the best outcomes of the last ARS (univariate/multivariate analysis)

-

B.

to determine whether the minimally invasive versus the open approach is superior for redo surgery

-

C.

to determine whether mesh repair versus direct suture is the superior method to treat the hiatal defect

The surgical technique for redo-fundoplication

The operation begins with adhesiolysis, the extent of which depends on the type of the previous procedure and access. Adhesiolysis is followed by thorough dissection of the hiatal crura and stepwise mobilization of the herniated fundic wrap. The distal part of the esophagus is then mobilized superiorly into the thorax and the hernia sac is reduced and resected. As a basic principle, the previous fundoplication is taken down in every patient, and if the hiatus is more than 5 cm, our protocol is to perform a mesh repair. After complete restoration to the initial anatomic structure, the procedure continues with the hiatal closure. First, the hiatal crura are approximated with simple interrupted 2–0 non-absorbable sutures. The simple sutured cruroplasty is placed as close as possible with the esophagus lying loosely between the crura with no narrowing. Mesh reinforcement is considered when simple cruroplasty with non-absorbable suture is impossible due to a large hiatal defect or the defect is too fibrotic to be re-approximated due to excessive tension.

The prosthetic reinforcement is then placed on the diaphragm and the approximated crura; it is fixed circumferentially with non-absorbable suture. Fixation is performed with great care to avoid tack injury.

The next step is to perform the redo-fundoplication with Nissen fundoplication (360° wrap) or Toupet fundoplication (270° wrap) in cases of dysphagia, fixing the stomach wrap to the crura and the esophagus by a non-absorbable 2–0 suture.

A drain is inserted only in cases of esophageal or stomach injury.

The same procedures are performed in laparoscopic/robotic or open techniques.

Postoperative management

In our practice, if intraoperative gastric or esophageal injury is undoubtedly ruled out, the patient begins a liquid diet during the first 24 h after surgery and then advances to solids. In case of complicated redo-fundoplication with gastric injury, the patient remains NPO (null by mouth) with a nasogastric tube for 24 h. Thereafter, we perform a CT scan with oral contrast or a barium swallow according to the surgeon’s preference to detect possible complications such as esophageal or gastric perforation or stenosis. The patient starts with a liquid diet and advances to small frequent meals as tolerated. If the patient is clinically well, he/she is discharged on day 4 or 5 with pain control and protons pumps inhibitors for one month.

Follow-up

According to our protocol, the initial follow-up visit occurs one month after the surgery. All patients with persistent or worsening symptoms after the primary intervention or the redo-fundoplication undergo further investigations such as a CT scan and gastroscopy. If failure of the primary redo-fundoplication is documented and the patient is symptomatic, the patient is planned for redo-fundoplication.

Patients with recurrent or worsening symptoms after the primary intervention or redo-fundoplication underwent more than one follow-up visit.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted by the Department of the Statistical Analysis Unit of the University of Montpellier using GraphPad Prism® and R software®. Descriptive data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables and proportions were compared using the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test. Logistic regression modeling was performed to identify significant variables to predict failure. The univariate analysis was performed using a logistic regression model where the predicted variables were the outcomes of the surgery in terms of persistence of symptoms (symptomatic versus asymptomatic) and the presence of complications. An OR > 1 represents a major risk of complication (complications versus no complications). The variables which were found to have a p value < 0.15 on univariate analysis were further analyzed using a multivariate logistic model (Table 1).

Results

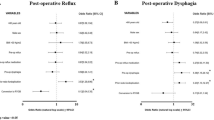

Significant variables influencing the persistence of symptoms after redo-ARS according to the univariate analysis (Table 2) were patient BMI, complications following the first fundoplication, type of redo-fundoplication, presence of a drain after redo-ARS, and the mean LOS after redo-ARS.

In multivariate analysis, the variables were type of redo-fundoplication, presence of a drain after redo-ARS, mean LOS after redo-ARS, and the use of mesh reinforcement.

Demographic data

Out of 975 patients undergoing surgery for hiatal hernia and GERD in the last 10 years, 73 (7.49%) underwent reoperation. Tables 2 and 3 show the general characteristics of the patients. Mean follow-up duration was 8.5 (1–107) months.

ARS technique

Forty-two (57.5%) cases were converted from Nissen to Toupet, 17 (23.3%) conserved the initial Nissen fundoplication, 9 (12.3%) conserved the initial Toupet fundoplication, and 5 (6.9%) were converted from Toupet to Nissen.

According to our findings, the best surgical treatment for redo-ARS was the Toupet fundoplication. Patients undergoing the Toupet procedure were less symptomatic at follow-up compared to those undergoing Nissen (p = 0.050, OR 0.314 univariate analysis; p = 0.005, OR 0.038 multivariate analysis) (Tables 2, 3).

Laparoscopic or open approach

Seventy-one (98%) cases were performed laparoscopically and only two cases were performed by the open approach. There was no significant difference between the laparoscopic and open approaches in terms of persistence of symptoms after redo-fundoplication (p value 0.251). However, the open approach was associated with perioperative complications including esophageal or gastric perforation and longer hospital stay (18–20 days vs 4–6 days with the minimally invasive approach, p = 0.020, OR 1.460 univariate analysis; p = 0.036, OR 1.721 multivariate analysis) (Tables 2, 3).

The role of mesh

Mesh repair during the first operation was not associated with an increased risk of symptoms at the time of the redo-ARS (p = 0.625). However, we found that using mesh for the redo-fundoplication (21%) was associated with a lower risk of having symptoms (p = 0.180, OR 0.33 univariate analysis; p = 0.020, OR 0.010 multivariate analysis) and improved quality of life during the postoperative follow-up period compared to direct suture alone.

Postoperative complications

The variables found to affect risk of postoperative complications in uni- and multivariate analyses were patient age and BMI, presence of postoperative dysphagia, and drain placement.

There were no perioperative deaths in our study. The complications were categorized based on the Clavien-Dindo Classification (Table 4). Eight patients (11%) had perioperative complications. Four patients experienced gastric perforation during the dissection of the old fundoplication. The gastric injury was recognized in all four cases and repaired intraoperatively with suturing. One patient experienced esophageal perforation which was unrecognized perioperatively and complicated by an esophageal leak postoperatively. The patient was managed conservatively by drain placement, and subsequent CT scan with contrast showed complete resolution of the leak. One patient had splenic injury treated conservatively. Two patients had respiratory complications including pneumothorax and pleural effusion. The presence of complications of redo-fundoplication was significantly associated with persistence of symptoms (p value 0.02) at follow-up. (Tables 5, 6).

In the univariate analysis of the factors associated with complications (Table 5) or the presence of symptoms after redo-fundoplication, we found that patients with a drain during the postoperative period were more likely to be symptomatic (p = 0.0037, OR 12.750). In addition, there was a significant relationship between BMI and persistence of symptoms after redo-ARS (p = 0.14, OR 0.822). In fact, patients with low BMI (< 25) were more prone to symptoms after redo-fundoplication.

Furthermore, regarding the primary intervention, univariate analysis showed that recurrence of symptoms after the initial intervention was slightly significant and was related to the persistence of GERD symptoms such as heartburn and regurgitation after the redo-ARS (p = 0.0637, OR 4.260) (Table 5).

Multivariate analysis (Table 6) showed that recurrence of dysphagia (p value 0.0637), drain placement during the redo-fundoplication (p = 0.038, OR 9.308), and age of the patient (p = 0.0619, OR 1.11) were associated with an increased risk of complications during the last ARS.

Risk of more than one redo-fundoplication

Out of 73 patients, 10 patients (13%) underwent more than one redo-ARS. There was a trend toward a significant association between mesh repair at the primary intervention and the risk of reoperation (p = 0.11). In addition, delay between the primary intervention and the first redo-fundoplication was a risk factor for a second redo-ARS (p = 0.12). A shorter delay between the primary intervention and the first redo-ARS was a risk factor for a second redo-ARS (p = 0.12, OR 0.82).

Discussion

At follow-up, minimally invasive partial Toupet redo-ARS was superior to Nissen fundoplication in terms of the rate of recurrent symptoms.

Arpad et al. recommend Roux-en-Y construction in cases of a large recurrent hernia and short esophagus [16] but does not mention superiority of one technique over the another.

In our practice in France, we mainly perform Toupet fundoplication, as it is associated with a lower incidence of dysphagia [17, 18]. In our study, during reoperation, 42 (57.5%) out of 73 patients had conversion from Nissen to Toupet fundoplication. Twenty-six (35.6%) conserved the initial fundoplication and only 5 patients (6.9%) had conversion from Toupet to Nissen.

In our cohort, 98% of the ARS was completed laparoscopically without the need for open conversion. We found that there is no significant difference between the laparoscopic and open approaches in terms of persistence of symptoms in the postoperative period; however, our findings are limited by the small number of open cases.

More cases of open redo-ARS must be evaluated to understand the difference between the two approaches. According to the literature, laparoscopic redo-ARS is considered safe and effective in treating recurrent HH and GERD, but there is no evidence of its superiority in terms of risk of recurrence [19,20,21]. Banki et al. found that there is an 8.5% recurrence rate after open laparoscopic redo-fundoplication [21].

Concerning the mesh repair, in the present study, mesh repair at reoperation led to fewer symptoms after redo-ARS than fundoplication without mesh repair. Mesh reinforcement should be used more frequently, and serious complications reported with mesh (migration and perforation) during redo surgery may outweigh its potential benefits. To our knowledge, there have been no studies analyzing the role of mesh in redo-ARS. A multicenter randomized trial showed a reduction in recurrence of hiatal hernia after primary laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair at 6 months with the use of biologic prosthetic mesh (9%) compared to primary closure (24%) [22]. In addition, a study by Lidor et al. showed that laparoscopic repair of a paraesophageal hernia resulted in excellent long-term quality of life. Based on the above findings and our study results, we recommend the use of mesh in redo-fundoplication.

In our study, we surprisingly found that patients with low BMI are at greater risk for persistent symptoms after redo-ARS. In fact, in the literature, we found the opposite results. Perez et al. reported that 31.3% of obese patients had symptom recurrence after the primary fundoplication, and this was significantly higher than that of the non-obese population [23]. Akimoto et al. also described a higher failure rate of fundoplication in obese patients with disrupted fundoplication being the most common pattern [24].

Furthermore, in our study, we found that postoperative dysphagia is associated with postoperative complications. The causes of postoperative dysphagia include stenosis associated with a tight fundoplication, hiatal hernia recurrence, and presence of mesh. This finding is consistent with the findings by Byrne et al., in which three-quarters of patients who underwent redo surgery required reoperation [25]. In addition, drain placement at redo-ARS was a risk factor for postoperative complications. Intraoperative complications such as gastric or esophageal perforation usually involve placing a drain.

The present study shows that patients with a drain in the postoperative period tend to be symptomatic during the follow-up period. The presence of a postoperative drain, above all, translates to laborious surgery or intraoperative complications. The drain itself is not predictive of postoperative symptoms.

The main limitation of our study is the retrospective nature and the absence of a quality of life assessment. In addition, some of the patients were lost to follow up after the reoperation. The number of recurrent cases may also be underestimated as some of the follow-up data do not include endoscopic or radiological studies.

In conclusion, redo-ARS remains a challenging operation in terms of the recurrence of symptoms and risks of complications despite the advantages of minimally invasive surgery.

Based on data from long-term follow-up, the conversion to partial 270° Toupet in redo-ARS is superior to Nissen in terms of recurrence of symptoms.

Abbreviations

- HH:

-

Hiatal hernia

- GERD:

-

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- ARS:

-

Anti-reflux surgery

- RF:

-

Redo-fundoplication

References

Hunter JG, Trus TL, Branum GD, Waring JP, Wood WC (1996) A physiologic approach to laparoscopic fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Surg 223(6):673–685

Peters JH, DeMeester TR, Crookes P, Oberg S, de Vos Shoop M, Hagen JA, Bremmer CG (1998) The treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease with laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: prospective evaluation of 100 patients with “typical” symptoms. Ann Surg 228(1):40–50

Viljakka M, Luostarinen M, Isolauri J (1997) Incidence of antireflux surgery in Finland 1988–1993. Influence of proton-pump inhibitors and laparoscopic technique. Scand J Gastroenterol 32(5):415–418

Frantzides CT, Carlson MA (1997) Laparoscopic redo Nissen fundoplication. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 7(4):235–239

Hinder RA, Perdikis G, Klinger PJ, DeVault KR (1997) The surgical option for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Med 103(5A):144S–148S

Laine S, Rantala A, Gullichsen R, Ovaska J (1997) Laparoscopic vs conventional Nissen fundoplication. A prospective randomized study. Surg Endosc 11(5):441–444

Dallemagne B, Weerts JM, Jehaes C, Markiewicz S (1996) Causes of failures of laparoscopic antireflux operations. Surg Endosc 10(3):305–310

Dallemagne B, Weerts JM, Jehaes C, Markiewicz S, Lombard R (1996) Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: preliminary report. Surg Laparosc Enodosc 1991:1:138–143

Watson DI, de Beaux AC (2001) Complications of laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Surg Endosc 15(4):344–352

Soper NJ, Dunnegan D (1999) Anatomic fundoplication failure after laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Ann Surg 229(5):669–676

Hinder RA, Klingler PJ, Perdikis G, Smith SL (1997) Management of the failed antireflux operation. Surg Clin North Am 77(5):1083–1098

Watson DI, Baigrie RJ, Jamieson GG (1996) A learning curve for laparoscopic fundoplication. Definable, avoidable, or a waste of time? Ann Surg 224(2):198–203

Hunter JG, Smith CD, Branum GD, Waring JP, Trus TL, Comwell M, Galloway K (1999) Laparoscopic fundoplication failures: patterns of failure and response to fundoplication revision. Ann Surg 230(4):595–604 discussion 604.

Floch NR, Hinder RA, Klingler PJ, Branton SA, Seelig MH, Bammer T, Filipi CJ (1999) Is laparoscopic reoperation for failed antireflux surgery feasible? Arch Surg 134(7):733–737

Granderath FA, Granderath UM, Pointner R (2008) Laparoscopic revisional fundoplication with circular hiatal mesh prosthesis: the long-term results. World J Surg 32(6):999–1007

Juhasz A, Sundaram A, Hoshino M, Lee TH, Mittal SK (2012) Outcomes of surgical management of symptomatic large recurrent hiatus hernia. Surg Endosc 26(6):1501–1508

Qin M, Ding G, Yang H (2013) A clinical comparison of laparoscopic Nissen and Toupet fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 23(7):601–604. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2012.0485

Strate U, Emmermann A, Fibbe C, Layer P, Zornig C (2008) Laparoscopic fundoplication: Nissen versus Toupet two-year outcome of a prospective randomized study of 200 patients regarding preoperative esophageal motility. Surg Endosc 22(1):21–30

Nageswaran H, Haque A, Zia M, Hassn A (2017) Laparoscopic redo anti-reflux surgery: case-series of different presentations, varied management and their outcomes. Int J Surg 46:(47–52)

Awad ZT, Anderson PI, Sato K, Roth TA, Gerhardt J, Filipi CJ (2001) Laparoscopic reoperative antireflux surgery. Surg Endosc 15(12):1401–1407

Banki F, Kaushik C, Roife D, Chawla M, Casimir R, Miller CC (2016) Laparoscopic reoperative antireflux surgery: a safe procedure with high patient satisfaction and low morbidity. Am J Surg 212(6):1115–1120

Frantzides CT, Madan AK, Carlson MA, Stavropoulos GP (2002) A prospective, randomized trial of laparoscopic polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) patch repair vs simple cruroplasty for large hiatal hernia. Arch Surg 137(6):649–652

Perez AR, Moncure AC, Rattner DW (2001) Obesity adversely affects the outcome of antireflux operations. Surg Endosc 15(9):986–989

Akimoto S, Nandipati KC, Kapoor H, Yamamoto SR, Pallati PK, Mittal SK (2015) Association of Body Mass Index (BMI) with patterns of fundoplication failure: insights gained. J Gastrointest Surg 19(11):1943–1948. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-015-2907-z

Byrne JP, Smithers BM, Nathanson LK, Martin I, Ong HS, Gotley DC (2005) Symptomatic and functional outcome after laparoscopic reoperation for failed antireflux surgery. Br J Surg 92(8):996–1001

Watson DI, Jamieson GG, Game PA, Williams RS, Devitt PG (1999) Laparoscopic reoperation following failed antireflux surgery. Br J Surg 86(1):98–101

Serafini FM, Bloomston M, Zervos E, Muench J, Albrink MH, Murr M, Rosemurgy AS (2001) Laparoscopic revision of failed antireflux operations. J Surg Res 95(1):13–18

Granderath FA, Kamolz T, Schweiger UM, Pointner R (2003) Failed antireflux surgery: quality of life and surgical outcome afterlaparoscopic refundoplication. Int J Colorectal Dis 18(3):248–253

Papasavas PK, Yeaney WW, Landreneau RJ, Hayetian FD, Gagné DJ, Caushaj PF, Macherey R, Bartley S, Maley RH Jr, Keenan RJ (2004) Reoperative laparoscopic fundoplication for the treatment of failed fundoplication. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 128(4):509–516

Oelschlager BK, Lal DR, Jensen E, Cahill M, Quiroga E, Pellegrini CA (2006) Medium- and long-term outcome of laparoscopicredo fundoplication. Surg Endosc 20(12):1817–1823

Khajanchee YS, O’Rourke R, Cassera MA, Gatta P, Hansen PD, Swanström LL (2007) Laparoscopic reintervention for failed antireflux surgery: subjective and objective outcomes in 176 consecutivepatients. Arch Surg 142(8):785–901 discussion 791.

Safranek PM, Gifford CJ, Booth MI, Dehn TC (2007) Results of laparoscopic reoperation for failed antireflux surgery: does the indication for redo surgery affect the outcome? Dis Esophagus 20(4):341–345

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the participant centers. Dr. Al Hashmi and Dr. F. Panaro certify that each had a “first author” role equally.

Funding

The study sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

The authors Al-Warith Al Hashmi, Guillaume Pineton de Chambrun, Regis Souche,Martin Bertrand, Vito De Blasi, Eric Jacques, Santiago Azagra, Jean Michel Fabre, Frédéric Borie, Michel Prudhomme, Nicolas Nagot, Francis Navarro, and Fabrizio Panaro have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Al Hashmi, AW., Pineton de Chambrun, G., Souche, R. et al. A retrospective multicenter analysis on redo-laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery: conservative or conversion fundoplication?. Surg Endosc 33, 243–251 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6304-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6304-z