Abstract

Background

The World Society for Emergency Surgery determined that for appendicitis managed with appendectomy, there is a paucity of evidence evaluating costs with respect to disease severity. The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) disease severity grading system is valid and generalizable for appendicitis. We aimed to evaluate hospitalization costs incurred by patients with increasing disease severity as defined by the AAST. We hypothesized that increasing disease severity would be associated with greater cost.

Methods

Single-institution review of adults (≥ 18 years old) undergoing appendectomy for acute appendicitis during 2010–2016. Demographics, comorbidities, operative details, hospital stay, complications, and institutional cost data were collected. AAST grades were assigned by two independent reviewers based on operative findings. Total cost was ascertained from billing data and normalized to median grade I cost. Non-parametric linear regression was utilized to assess the association of several covariates and cost.

Results

Evaluated patients (n = 1187) had a median [interquartile range] age of 37 [26–55] and 45% (n = 542) were female. There were 747 (63%) patients with Grade I disease, 219 (19%) with Grade II, 126 (11%) with Grade III, 50 (4%) with Grade IV, and 45 (4%) with Grade V. The median normalized cost of hospitalization was 1 [0.9–1.2]. Increasing AAST grade was associated with increasing cost (ρ = 0.39; p < 0.0001). Length of stay exhibited the strongest association with cost (ρ = 0.5; p < 0.0001), followed by AAST grade (ρ = 0.39), Clavien–Dindo Index (ρ = 0.37; p < 0.0001), age-adjusted Charlson score (ρ = 0.31; p < 0.0001), and surgical wound classification (ρ = 0.3; p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

Increasing anatomic severity, as defined by AAST grade, is associated with increasing cost of hospitalization and clinical outcomes. The AAST grade compares favorably to other predictors of cost. Future analyses evaluating appendicitis reimbursement stand to benefit from utilization of the AAST grade.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Acute appendicitis is a common disease with an estimated incidence of 9.38 per 10,000 people per year in the United States (US) [1]. Management in the acute setting often requires appendectomy. National estimates of surgical disease burden indicate that appendicitis is voluminous and accounts for the majority of emergency general surgery (EGS) hospitalizations in the US [2, 3]. Additionally, appendectomy has been highlighted as a procedure with one of the most disproportionate clinical burdens in EGS [4]. Recent estimates suggest that EGS costs account for a significant proportion of healthcare cost in the US [5]. Moreover, the costs associated with EGS diseases vary widely throughout the country and have increased with time due to an aging population [3]. Among these EGS diseases, appendicitis ranked among the top seven most costly with annual nationwide costs estimated to be in the billions of US dollars [3]. Recently, the World Society for Emergency Surgery (WSES) defined guidelines for the rational management of appendicitis globally [6]. Therein, the WSES determined that a sufficient cost analysis based on patient disease severity and comorbidity does not exist.

Anatomic severity in appendicitis has historically been classified as either simple or complex. This binary approach to disease severity neglects the individual nuances and variation of disease across patient populations thereby limiting comparison of patient outcomes. In response, the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) established new clinical, imaging, operative, and pathologic criteria for the assessment of disease severity in appendicitis, as well as other EGS diseases [7,8,9]. This AAST EGS grade is a five-level Grade (I–V) that corresponds to increasing degrees of inflammation. Subsequent study demonstrated that important clinical outcomes, including duration of stay and morbidity, are associated with increasing anatomic severity of appendicitis as defined by the AAST EGS grade [10]. This work in an adult population, as well as a follow-up study in a pediatric population, reported substantial (Cohen’s κ = 0.79) to near perfect two-reviewer agreement when grades for appendicitis were assigned based on operative findings [10, 11].

EGS diseases vary significantly depending on patient factors, such as the involved injured organ(s)/tissue(s), presenting physiology, and extent of patient comorbidity. As a result, wide variation exists in the management of these diseases. In order to provide a granular and equitable comparison of outcomes, including cost analyses for appendicitis, utilization of a standardized disease severity classification system is necessary. The aim of this study was to perform a cost analysis in patients with acute appendicitis managed with appendectomy. We hypothesized that patients with increased anatomic severity, as defined by the AAST EGS grade, would demonstrate incremental increases in the cost of care from admission to dismissal.

Methods

This was a single-institution, retrospective review undertaken by the authors. Institutional review board approval was obtained prior to the start of the investigation.

Patient cohort

Patients were identified from a previously collected retrospective database of adults (≥ 18 years of age) that underwent appendectomy for acute appendicitis from January 2010 to July 2016. This cohort did not include patients that did not receive a post-procedure diagnosis of acute appendicitis, underwent interval appendectomy and non-operative management, were pregnant, or demonstrated malignant disease (appendiceal tumor).

Patient characteristics, procedure, and clinical outcomes

From the aforementioned database, data on baseline demographics, preexisting comorbidities, presenting physiology, leukocyte count (109 cells/L), duration of prehospital symptoms (abdominal pain, fever, and emesis), appendectomy procedure type (laparotomy, McBurney’s incision, laparoscopy, laparoscopy converted to laparotomy), and surgical wound classification as defined by CDC guidelines were utilized [12]. An age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index was calculated using assigned diagnostic ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM coding [13,14,15]. Clinical outcomes retrieved from the database included surgical complications classified using the Clavien–Dindo classification system and duration of hospital stay [16].

AAST EGS grade assignment

The AAST EGS grade is a five-level Grade (I–V) that can be generated from clinical, imaging, operative, and pathologic criteria. It is used to describe disease severity for several EGS conditions. In appendicitis for example, Grade I represents acute inflammatory appendicitis, Grade II suppurative inflammatory appendicitis, Grade III perforated appendicitis, Grade IV perforated appendicitis with formation of abscess, and Grade V perforated appendicitis with feculent peritonitis. Previously, two reviewers utilized operative report findings to assign an AAST EGS grade for appendicitis to each patient in the database, as has been done in earlier retrospective work [7, 10, 17, 18]. Only operative report findings were utilized as not all patients underwent preoperative imaging (cross-sectional or ultrasonography) and procedure specimens are not routinely sent for pathological evaluation at our institution. There was substantial agreement between the two reviewers (Cohen’s κ = 0.72). Grading disagreements were adjudicated by a third reviewer and the final assigned AAST EGS grade was utilized for all outcome analyses in the present study.

Cost of hospitalization

The primary outcome was the total cost of a patient’s hospitalization calculated as the sum of all direct and indirect costs incurred as a result of each resource utilized from admission to discharge. We elected to use the total cost of care, as opposed to the total charged or billed for care, since cost is considered a more accurate measure of expenses incurred. The total hospital cost incurred by each patient was divided by the median cost of AAST Grade I disease to produce a “normalized” cost that complies with institutional policies that restrict the reporting of cost. The association of cost with predictors such as Clavien–Dindo Index, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and length of hospital stay was evaluated secondarily.

Statistical analyses

Patients were stratified by AAST disease severity grade. All normally distributed continuous variables were described using means with standard deviation (SD). Continuous variables with gross skewness were reported using a median with interquartile range (IQR). Nominal variables were formatted as frequencies with actual variable count (n). Study of the relationship between AAST EGS grade and covariates was accomplished using the Cochran Armitage test for trend and linear regression. The relationship between cost and predictors was evaluated using linear regression or one-way analysis of variance where appropriate. When the assumptions of linear regression were not met, Spearman’s Rho and Theil–Sen estimator of fit were used. Similarly, a Kruskal–Wallis test was utilized when the assumptions of one-way analysis of variance were unmet. Individual pair analyses were performed using two-sample hypothesis testing and alpha was adjusted for multiple comparisons using a Bonferroni correction. All data analyses were performed using JMP Pro 13 (SAS Institute Inc.) with alpha set at 0.05. Figures were generated using GraphPad Prism 7 (©2017 GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Results

Patient characteristics, procedure, and clinical outcomes

There were 1187 patients that underwent appendectomy for acute appendicitis from January 2010 to July 2016. The distribution of AAST anatomic severity grades consisted of Grade I (n = 747, 63%), Grade II (n = 219, 19%), Grade III (n = 126, 11%), Grade IV (n = 50, 4%), and Grade V (n = 45, 4%). Baseline patient characteristics, procedural parameters, and clinical outcomes are stratified by AAST anatomic severity grade in Table 1.

Cost of hospitalization

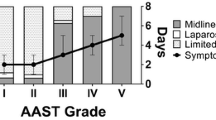

The median [IQR] normalized cost of hospitalization was 1 [0.9–1.1] for Grade I, 1 [0.9–1.2] for Grade II, 1.4 [1.1–2] for Grade III, 1.6 [1.2–2.2] for Grade IV, and 2.2 [1.4–3.4] for Grade V. The cost of hospitalization differed significantly between AAST EGS grades for appendicitis (p < 0.0001; Fig. 1). Between Grades I and II, the difference in cost was not significant (adjusted p = 0.8). The costs of Grade III disease were significantly higher than those of Grades I and II (adjusted p < 0.0001), but similar to those of Grade IV (adjusted p = 0.7). Grade V disease costs were significantly higher than those of Grades III and IV (adjusted p < 0.0001, p = 0.04). Normalized cost was estimated to have increased, on average, by 0.12 per increase in AAST EGS grade (Spearman’s ρ = 0.39; p < 0.0001; Fig. 1). Patients with Grade I disease, the most numerous grade with the lowest variation in cost, incurred 49% of the total normalized cost for the cohort, Grade II 18%, Grade III 15%, Grade IV 7%, and Grade V 11%.

Linear regression of normalized cost and covariates. Non-parametric, linear regression of normalized cost by AAST anatomic severity grade (ρ = 0.39), age-adjusted Charlson Index (ρ = 0.31), Clavien–Dindo Index (ρ = 0.37), and length of hospital stay (ρ = 0.5). The shaded region surrounding each fitted line represents the 95% confidence interval

Cost was associated with age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index (estimated 0.04 increase per index score increase; Spearman’s ρ = 0.31; p < 0.0001), complication severity as defined by Clavien and Dindo (estimated 0.15 increase per grade increase; Spearman’s ρ = 0.37; p < 0.0001), length of hospital stay (estimated 0.13 increase per additional day of stay; Spearman’s ρ = 0.5; p < 0.0001), and operative duration (estimated 0.003 increase per additional minute of operative time; Spearman’s ρ = 0.28; p < 0.0001). Additionally, there was an association between cost and wound classification (estimated 0.11 increase per class increase; Spearman’s ρ = 0.3; p < 0.0001). Cost was not associated with operative approach (p = 0.3). Length of stay exhibited the strongest association with cost, followed by the AAST EGS grade, Clavien–Dindo index, and age-adjusted Charlson score (Fig. 1).

Discussion

EGS disease hospitalizations have the greatest cost burden of all emergency hospitalizations in the United States each year. This financial strain on the healthcare system and society is only expected to increase as the US population ages [5]. Appendicitis is a common EGS disease with a broad range of clinical presentations and disease severity [1]. Severe disease can necessitate extensive stay in intensive care settings and lead to death [10, 19]. In this study, we utilized the AAST EGS disease severity grading system to enable an equitable comparison of outcomes in appendicitis. We demonstrated that for increasing AAST EGS grade, there was an association with increasing cost. We also determined that, compared with other potential covariates, the AAST EGS grade was a strong candidate to predict patient cost. This has several implications for future reimbursement analysis considering appendicitis and, potentially, other common EGS diseases when disease severity is stratified using the AAST EGS grade.

First, our data highlight that increasing AAST EGS grade is associated with increasing cost of care for appendicitis. Moreover, the strength of this association was comparable to that of other predictors of cost such as length of stay, complications defined by Clavien–Dindo Index, and age-adjusted Charlson Index. This finding confirms that patients with greater severity of disease incur greater costs than those with less severe disease—likely due to greater rates of complications, re-interventions, and increased duration of stay. Pair-wise analysis demonstrated significant differences in cost between AAST Grades II and III as well as Grades IV and V. These findings may suggest that patients with extension of their disease beyond the appendix (perforation) and involvement of the entire abdomen (diffuse peritonitis) are more likely to necessitate higher levels of care. Although patients with Grade IV and V disease comprised 8% (n = 95) of the cohort, they disproportionately accounted for 17% of the total cost. This supports reports that estimates of increasing healthcare costs in the US are, at least in part, due to patients with the most severe disease [3].

Operative duration exhibited a weak relationship with cost while operative approach had no association. Furthermore, the choice of operative approach did not differ significantly between severity grades in this study. The lack of association between procedure and cost suggests that a wider spectrum of appendicitis might be managed with less invasive techniques [20]. In addition to the ability to perform less invasive procedures for increasingly more severe disease, the role of laparoscopy has been demonstrated to reduce a variety of patient, disease, and procedure-specific costs. Future analyses evaluating common EGS disease conditions should consider improving cohort stratification using AAST EGS grading in order to appraise cost in a more granular manner and extrapolate findings to other populations.

Patient comorbidity at presentation, as measured by age-adjusted Charlson score, was also associated with cost of care. This is an intuitive finding since we expect patients with additional comorbidities to utilize more care resources and require longer hospital stays, incurring greater costs. Surgical wound classification was another predictor of morbidity associated with cost. Wound class is a well-established risk factor for the development of surgical site infections and has been previously associated with the disease severity of surgically managed appendicitis [21, 22]. In our study, increasing anatomic severity, defined by the AAST EGS grade, was also associated with wound class. However, the AAST EGS grade had a stronger relationship with the cost of hospitalization than wound type.

Historically, retrospective study of appendicitis has yielded important findings that have later upended established clinical paradigms. The widely utilized Alvarado scoring system for the diagnosis of appendicitis is one such example [23]. In the present study, retrospectively assigned AAST EGS grades using operative findings enabled granular appraisal of the relationship between disease severity and outcomes, such as cost. We submit that the ability to retrospectively evaluate disease severity using the AAST EGS grade makes it a promising disease benchmarking tool. Moreover, we see potential for application of the grade to existing quality reporting and clinical resource application practices. Study of appendicitis using large national datasets such as the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, have reported rates of comorbidity and mortality similar to those in this cohort [24, 25]. Thus, we believe that the retrospective application of the AAST EGS grade may generalize well to such secondary data sources. Prospective application of this score in clinical practice may provide additional benefit, but further study is needed to determine appropriate application and how it might be used to decrease costs. One potential avenue for cost reduction may be through improved early identification of patients with high severity appendicitis, prompting earlier intervention where attempted medical management with a subsequent delayed, more difficult intervention would otherwise occur.

We consider several important and inherent limitations to this study. Foremost is the retrospective nature of the work, specifically the assignment of AAST EGS grades based on operative documentation. This may have resulted in failure to account for the true severity of disease since preoperative severity was not uniformly assessed for this cohort. It is also important to consider that the study findings are limited by the single-institution design, which may not translate well to other institutions of varying size, focus, and location. This is increasingly true given that the setting of the study is a tertiary center that overwhelmingly cares for patients with high comorbidity and acute physiologic impairment. Additionally, the study excluded patients that underwent non-operative management. This may have biased the analyses of cost since Grade IV appendicitis is often initially managed with percutaneous drain placement at our institution. Further study is necessary to better understand the role of grading anatomic severity in the overall cost of care for appendicitis and we are addressing this in a prospective manner currently. Finally, this study did not explore additional confounders and the interaction between the reported and unreported predictors of cost. Caution should be exercised when making assertions regarding the univariate effects and relationships of the studied predictors with cost.

Conclusions

Increasing anatomic severity, as defined by AAST anatomic severity grade, is associated with increasing cost of hospitalization in acute appendicitis managed surgically. The AAST EGS grade compares favorably with other predictors of cost including length of stay, the Clavien–Dindo Index, and the Charlson comorbidity index. Higher severity disease incurs disproportionate costs. Stratification of disease severity using the AAST EGS grade is trivial and has potential to improve reimbursement practices.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available in accordance with institutional policy on the reporting of billing data. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of Mayo Clinic.

Abbreviations

- AAST:

-

American Association for the Surgery of Trauma

- EGS:

-

Emergency general surgery

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- US:

-

United States

- WSES:

-

World Society for Emergency Surgery

References

Buckius MT, McGrath B, Monk J, Grim R, Bell T, Ahuja V (2012) Changing epidemiology of acute appendicitis in the United States: study period 1993-2008. J Surg Res 175:185–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2011.07.017

Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, Crockett SD, McGowan CE, Bulsiewicz WJ et al (2012) Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology 143:1179–1187.e3. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.002

Ogola GO, Shafi S (2016) Cost of specific emergency general surgery diseases and factors associated with high-cost patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 80:265–271. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000000911

Scott JW, Olufajo OA, Brat GA, Rose JA, Zogg CK, Haider AH et al (2016) Use of national burden to define operative emergency general surgery. JAMA Surg 2115:e160480. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2016.0480

Ogola GO, Gale SC, Haider A, Shafi S (2015) The financial burden of emergency general surgery: national estimates 2010 to 2060. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 79:444–448. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000000787

Di Saverio S, Birindelli A, Kelly MD, Catena F, Weber DG, Sartelli M et al (2016) WSES Jerusalem guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis. World J Emerg Surg 11:34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-016-0090-5

Shafi S, Aboutanos M, Brown CV-R, Ciesla D, Cohen MJ, Crandall ML et al (2014) Measuring anatomic severity of disease in emergency general surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 76:884–887. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e3182aafdba

Crandall ML, Agarwal S, Muskat P, Ross S, Savage S, Schuster K et al (2014) Application of a uniform anatomic grading system to measure disease severity in eight emergency general surgical illnesses. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 77:705–708. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000000444

Tominaga GT, Staudenmayer KL, Shafi S, Schuster KM, Savage SA, Ross S et al (2016) The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Grading Scale for 16 emergency general surgery conditions. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 81:1. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000001127

Hernandez MC, Aho JM, Habermann EB, Choudhry AJ, Morris DS, Zielinski MD (2017) Increased anatomic severity predicts outcomes: validation of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma’s Emergency General Surgery score in appendicitis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 82:73–79. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000001274

Hernandez MC, Polites SF, Aho JM, Haddad NN, Kong VY, Saleem H et al (2018) Measuring anatomic severity in pediatric appendicitis: validation of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Appendicitis Severity Grade. J Pediatr 192:229–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.09.017

Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR (1999) Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 20:250-78-80. https://doi.org/10.1086/501620

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA (1992) Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 45:613–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi J-C et al (2005) Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 43:1130–1139

Clavien P, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD et al (2009) The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications. Ann Surg 250:187–196. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b13ca2

Savage SA, Klekar CS, Priest EL, Crandall ML, Rodriguez BC, Shafi S et al (2015) Validating a new grading scale for emergency general surgery diseases. J Surg Res 196:264–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2015.03.036

Baghdadi YMK, Morris DS, Choudhry AJ, Thiels CA, Khasawneh MA, Polites SF et al (2016) Validation of the anatomic severity score developed by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma in small bowel obstruction. J Surg Res 204:428–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2016.04.076

Hernandez MC, Kong VY, Aho JM, Bruce JL, Polites SF, Laing GL et al (2017) Increased anatomic severity in appendicitis is associated with outcomes in a South African population. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 83:175–181. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000001422

Di Saverio S, Mandrioli M, Sibilio A, Smerieri N, Lombardi R, Catena F et al (2014) A cost-effective technique for laparoscopic appendectomy: outcomes and costs of a case-control prospective single-operator study of 112 unselected consecutive cases of complicated acute appendicitis. J Am Coll Surg 218:e51–e65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.003

Putnam LR, Levy SM, Holzmann-Pazgal G, Lally KP, Lillian SK, Tsao K (2015) Surgical wound classification for pediatric appendicitis remains poorly documented despite targeted interventions. J Pediatr Surg 50:915–918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.03.008

Wang-Chan A, Gingert C, Angst E, Hetzer FH (2017) Clinical relevance and effect of surgical wound classification in appendicitis: retrospective evaluation of wound classification discrepancies between surgeons, Swissnoso-trained infection control nurse, and histology as well as surgical site infection rates by wound class. J Surg Res 215:132–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2017.03.034

Alvarado A. A practical score for the early diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15:557–564

Page AJ, Pollock JD, Perez S, Davis SS, Lin E, Sweeney JF (2010) Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy: an analysis of outcomes in 17,199 patients using ACS/NSQIP. J Gastrointest Surg 14:1955–1962

Senekjian L, Nirula R (2013) Tailoring the operative approach for appendicitis to the patient: a prediction model from national surgical quality improvement program data. J Am Coll Surg 216:34–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.08.035

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EJF designed the study, collected data, performed the analyses, and wrote the manuscript. MCH participated in the design of the study, collection and analysis of the data, and was a major contributor to the writing of the manuscript. JMA contributed to the design of the study and the writing of the manuscript. MDZ oversaw the design of the study, data collection, and writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Eric J. Finnesgard, Matthew C. Hernandez, Johnathon M. Aho, and Martin D. Zielinski declare that they have no competing interests and financial ties to disclose.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Institutional review board approval was obtained and the requirement for individual consent was waived prior to the start of the investigation.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Finnesgard, E.J., Hernandez, M.C., Aho, J.M. et al. The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Emergency General Surgery Anatomic Severity Scoring System as a predictor of cost in appendicitis. Surg Endosc 32, 4798–4804 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6230-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6230-0