Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is considered safe and effective even as conversion procedure after primary bariatric operations. The correlation between gastric pouch volumes and patients weight loss remains unclear.

Methods

To assess a correlation between the gastric remnant size and the weight loss, we reviewed 49 consecutive barium swallow UGS performed at our institute from August 2012 through May 2014 in LSG patients with symptoms and/or unsatisfactory weight loss. The anteroposterior (AP), laterolateral (LL) and vertical (CC) diameters of the gastric pouch were measured to calculate the volume by the formula of the ellipsoid (AP × LL × CC × 0.5). Patients were divided in two groups: group 1 without gastric pouch (n = 36) and group 2 with gastric pouch (n = 13). Correlation between pouch volume and weight loss data was calculated with t Student’s and Fisher tests to compare the percent excess body mass index (BMI) and percent excess body mass loss (EBL) between two groups, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The mean percent EBL was 26.54 ± 11.02 and 27.12 ± 12.35 kg/m2 in groups with and without pouch, respectively. The mean volume of the pouch after LSG was 17.13 ± 21.56 mm3. Pouch volume, when present, was not significantly correlated to weight loss (P = 0.88 95 % CI, CL 19.88–33.20 group 2; CL 22.94–31.30 group 1).

Conclusions

No statistical correlation was found between the volume of the gastric pouch and weight loss (percent EBL) after LSG in symptomatic or with unsatisfactory weight loss patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The epidemic obesity is one of the most serious public health problems across different countries. The association of obesity with type II diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia and other comorbidities—the so called “metabolic syndrome”—is well established and significantly increases the cardiovascular risk.

The most important preventive measure aiming at curbing the effects of obesity involves lifestyle changes, including modifications in diet and physical activity [1, 2]. Current surgical approaches include restrictive, malabsorptive or combined restrictive/malabsorptive procedures [3]. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) was initially discovered as first-step surgery prior to a more complex procedure (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or biliopancreatic diversion-duodenal switch [4]) to reduce the overall operative risk in super-obese or high-risk patients [5–7]. Now it is considered a full primary bariatric procedure, safe and effective even as conversion procedure after failure or complications of other bariatric operations [8, 9]. Several different mechanisms have been postulated to lead to weight loss after LSG, such as the reduced expansibility and capacity of the sleeved stomach [10], the higher pressure induced by solid food intake [11], improved mitochondrial respiration [12] and insulin sensitivity [13, 14], and lower plasma levels of ghrelin [15], mainly produced in the fundic region by specialized gastric cells [16, 17]. In common clinical practice, the radiological follow-up was usually indicated only for patients with symptoms or unsatisfactory weight loss curve, but the correlation between gastric fundus at follow-up upper gastrointestinal series (UGS) and weight loss remains unclear [18]. Radiologists and surgeons need to become familiar with the postoperative radiological appearances of LSG. A multi-disciplinary approach to the management of these patients is essential in order to maximize their positive outcomes.

In this study, we evaluate the gastric pouch using UGI study because, according to some authors, we believe that weight loss should be better without a pouch [19–22]. Gastric cell in the fundic region produces ghrelin [15–17], and a gastric pouch may cause a lower satiety control resulting in reduced weight loss or weight regain.

Materials and methods

Our retrospective study involved a sample of 49 patients [45 females, four males, mean age = 49 years, (range 23–75)] who underwent LSG in the Centre of Excellence for Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery of Padua’s University Hospital from July 2005 to December 2013 and that were investigated with radiographic examination between August 2012 and May 2014 at the Institute of Radiology, Padua University.

During follow-up, UGS with barium swallow were requested for symptoms and/or unsatisfactory weight loss (<25 % EBL after 6 months) [20].

The mean interval from surgery to UGS was 1.96 ± 2.48 years.

Patients were asked to fasten for at least 4 h before barium swallow.

Patients’ data (height, weight before surgery, lowest weight reached, present weight, place and date of surgery) were retrieved/collected, and symptoms if present registered. Pre-surgical and current BMI were derived from these data.

All exams were performed with Siemens AXIOM Iconos R200 (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany), administering an oral suspension obtained with barium diluted in 100 ml of water (Prontobario H.D., 98.45 g of barium sulfate) (Bracco, Milan, Italy).

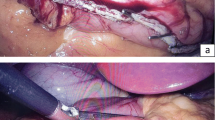

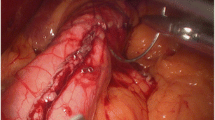

Images have been registered at a frequency of two frames per second, with patient in orthostatic position. A first plain anteroposterior radiogram of the upper abdomen was obtained (Fig. 1). Then, the patient in the upfront position was instructed to swallow a small amount of contrast medium, registering the passage of barium from the middle–distal third of the esophagus through the stomach (Fig. 2). A second series of images was obtained from the lateral view with the same characteristics (Fig. 3). When needed, further projections were added to better evaluate pouches in association with provocative maneuvers to stimulate gastroesophageal reflux, even in supine position. Gastric pouch was defined as “a gastric fundus remnant or a saccular dilatation of the cranial gastric portion.” It appears like a re-dilatation of the gastric tubule, and it can also be appreciated as an air-fluid level in the left upper abdominal quadrant in plain frontal radiography (Fig. 1). The passage of barium through the pylorus into the duodenum was also recorded.

Same patient as in Fig. 1, standing in orthostatic, frontal position; after the first sip of contrast medium, an ellipsoid-shaped plus image appears in the first trait of the sleeved stomach, protruding toward the right side. The air-fluid level is still visible

Each study was assessed by two expert gastrointestinal tract Radiologists. When a pouch was identified, it was measured along its three major axes (anteroposterior AP, cranio–caudal CC, and laterolateral LL diameters), and the volume was calculated with the ellipsoid formula (AP × CC × LL × 0.5). Patients were divided into two groups: group 1, without a detectable pouch (n = 36), and group 2 with a detectable gastric pouch (n = 13).

Statistical analysis was performed in collaboration with the Biostatistic and Epidemiology Department of Padua University. t Student’s test was calculated to compare percent EBL between group 1 and group 2, and also to evaluate any correlations between weight loss and pouch volume.

Results

Twenty-six patients had a history of previous abdominal surgery: 13/49 laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB) before LSG, 9/49 cholecystectomy, 2/49 abdominoplasty and 4/49 other major abdominal surgery.

Twenty-seven patients experienced one or more of these symptoms: dysphagia (2/49), dyspepsia (8/49), reflux and heartburn (18/49), vague stomachache (4/49), nausea and/or vomit (6/49). The remaining 22 patients were asymptomatic, except from unsatisfactory weight loss or weight regain.

A gastric pouch was found in 13 out of 49 patients (Group 2), while the 36 remaining patients had no such evidence (Group 1). The mean volume of the pouch was 17.13 ± 21.56 mm3.

In group 2 (13 pts), mean pre-surgical BMI was 42.75 ± 7.40 kg/m2, mean postsurgical BMI = 25.50 ± 6.82 kg/m2 and percent EBL 26.54 ± 11.02. In group 1 (36 pts), they were: mean pre-surgical BMI = 53.25 ± 7.60 kg/m2, mean postsurgical BMI = 35.65 ± 6.24 kg/m2 and percent EBL = 27.12 ± 12.35 (Table 1).

At statistical analysis, there was no significant difference in terms of percent EBL between the two groups (P = 0.88 95 % CI, CL 19.88–33.20 group 2; CL 22.94–31.30 group 1)(Fig. 4).

Discussion

LSG is a restrictive surgical approach, valuable for the treatment of morbid obesity (BMI > 35 kg/m2). The most relevant early surgical complications are leaks, bleeding and stenosis [23], while the most controversial long-term issues are related with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) [24] and dilation of the gastric tubule. The major aim of this operation is the reduction in the gastric capacity, the final shape resulting in one of these three patterns according to Werquin’s classification: real tubular, partial fundus persistence variant and partial antrum persistence variant [25, 26]. The first one is the most desirable in order to obtain the best results in weight loss. The fundic persistance may be either a surgical strategy aimed to preserve anti-reflux mechanism or reflect technical difficulties in dissection and resection of gastric fundus. The large amount of perivisceral fat in severely obese patients and a large posterior portion of proximal stomach (posterior “cascade”) can greatly impair complete resection of the gastric fundus [27]. The third pattern may also depend on surgeon’s will to preserve more antrum or may be caused by a misplacement of the bougie during staplers application.

According to some authors, even a small amount of gastric fundus may have a protective role against GERD, as its complete resection could damage the sling fibers at His angle [28], causing a hypotonic LES. On the contrary, Toro et al. [29] demonstrated a major recurrence of GERD symptoms in patients with upper pouch.

As far as gastric emptying, Melissas et al. [30] reported an accelerated stomach voiding after sleeve gastrectomy, due to altered contractility of proximal stomach and to the absence of compliance of the remnant. This faster transit seems to increase glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP1) secretion from the ileal cells, reducing peristalsis and promoting satiety. Moreover, accelerated emptying is related with better weight loss but also with GERD and dumping symptoms [31].

Re-dilatation of the proximal segment of the stomach after sleeve gastrectomy represents one of the most frequent long-term complications reported in literature, requiring surgical revision in about 4.5 % of patients [32]. Hints of a gastric pouch can also be appreciated as an air-fluid level in the left upper abdominal quadrant in plain frontal radiography (Fig. 1). Whenever evident, a barium swallow UGS, with both frontal and lateral projections to calculate the three diameters of the pouch and consequently its volume (Figs. 2, 3), is needed. Some studies reported that this might cause a reduced weight loss or weight regain [3]. Our results, along with some others, did not confirm these findings [24, 33], showing that the presence of a fundic pouch did not significantly affect weight loss, and, if present, pouch volume was not correlated with BMI reduction. From our data, the pouch did not seem to act as a functional reservoir.

The eventual presence of a “gender effect” is not so evident in our series, as the low rate of male patients does not allow to draw any definitive consideration. The small amount of patients with pouch and the fact that our population is not that homogeneous represent the main limitation to the study.

Another important limitation of this retrospective study is the inclusion of patients who had previous surgery before LSG, mainly LAGB. It is well known that some pouch outlasts band removal, even when LSG is staged 3–6 months after band removal. This reflects a not-real-total reversibility of the device and can introduce some significant bias as far as LSG results.

Conclusions

Our results seem to show that the evidence of a proximal pouch after LSG has no significant impact on weight loss and does not “per se” mandate revisional surgery, especially if they do not complain any symptoms. Further studies and larger and more homogeneous series are required to validate our conclusions.

References

Jarosz M, Rychlik E, Respondek W (2007) Counteraction against obesity—is it possible? Adv Med Sci 52:232–239

OECD (2010) Obesity and the economics of prevention: fit not fat. OECD Publishing, Paris

Pomerri F, Foletto M, Allegro G, Bernante P, Prevedello L, Muzzio PC (2011) Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy—radiological assessment of fundus size and sleeve voiding. Obes Surg 21(7):858–863

Mognol P, Chosidow D, Marmuse JP (2005) Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as an initial bariatric operation for high-risk patients: initial results in 10 patients. Obes Surg 15:1030–1033

Prosch H, Tscherney R, Kriwanek S, Tscholakoff D (2008) Radiographical imaging of the normal anatomy and complications after gastric banding. Br J Radiol 81(969):753–757

Scheirey CD, Scholz FJ, Shah PC, Brams DM, Wong BB, Pedrosa M (2006) Radiology of the laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedure: conceptualization and precise interpretation of results. Radiographics 26(5):1355–1371

Blachar A, Federle MP (2002) Gastrointestinal complications of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery in patients who are morbidly obese: findings on radiography and CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 179:1437–1442

Jacobs M, Bisland W, Gomez E, Plasencia G, Mederos R, Celaya C, Fogel R (2010) Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a retrospective review of 1- and 2-year results. Surg Endosc. doi:10.1007/s00464-009-0619-8

Barnard Stuart A, Rahman Habib, Foliaki Antonio (2012) The postoperative radiological features of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 56(4):425–431

Weiner RA, Weiner S, Pomhoff I, Jacobi C, Makarewicz W, Weigand G (2007) Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy—influence of sleeve size and resected gastric volume. Obes Surg 17:1297–1305

Kueper MA, Kramer KM, Kirschniak A, Königsrainer A, Pointner R, Granderath FA (2008) Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: standardized technique of a potential standalone bariatric procedure in morbidly obese patients. World J Surg 32:1462–1465

Nijhawan S, Richards W, O’Hea MF, Audia JP, Alvarez DF (2013) Bariatric surgery rapidly improves mitochondrial respiration in morbidly obese patients. Surg Endosc. doi:10.1007/s00464-013-3125-y

Roslin MS, Dudiy Y, Brownlee A, Weiskopf J, Shah P (2014) Response to glucose tolerance testing and solid high carbohydrate challenge: comparison between Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, vertical sleeve gastrectomy, and duodenal switch. Surg Endosc. doi:10.1007/s00464-013-3176-0

Grong E, Arbo IB, Thu OK, Kuhry E, Kulseng B, Mårvik R (2015) The effect of duodenojejunostomy and sleeve gastrectomy on type 2 diabetes mellitus and gastrin secretion in Goto-Kakizaki rats. Surg Endosc. doi:10.1007/s00464-014-3732-2

Basso N, Capoccia D, Rizzello M, Abbatini F, Mariani P, Maglio C, Coccia F, Borgonuovo G, De Luca ML, Asprino R, Alessandri G, Casella G, Leonetti F (2011) First-phase insulin secretion, insulin sensitivity, ghrelin, GLP-1, and PYY changes 72 h after sleeve gastrectomy in obese diabetic patients: the gastric hypothesis. Surg Endosc. doi:10.1007/s00464-011-1755-5

D’Hondt M, Vanneste S, Pottel H, Devriendt D, Van Rooy F, Vansteenkiste F (2011) Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as a single-stage procedure for the treatment of morbid obesity and the resulting quality of life, resolution of comorbidities, food tolerance, and 6-year weight loss. Surg Endosc. doi:10.1007/s00464-011-1572-x

Abdemur A, Slone J, Berho M, Gianos M, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ (2014) Morphology, localization, and patterns of ghrelin-producing cells in stomachs of a morbidly obese population. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 24(2):122–126

Shah S, Shah V, Ahmed AR, Blunt DM (2011) Imaging in bariatric surgery: service set-up, post-operative anatomy and complications. Br J Radiol 84(998):101–111

Cesana G, Uccelli M, Ciccarese F, Carrieri D, Castello G, Olmi S (2014) Laparoscopic re-sleeve gastrectomy as a treatment of weight regain after sleeve gastrectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg. doi:10.4240/wjgs.v6.i6.101

Iannelli A, Schnecj AS, Noel P, Ben Amor I, Krawczykowski D, Gugenheim J (2011) Re-sleeve gastrectomy for failed laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a feasibility study. Obes Surg. doi:10.1007/s11695-010-0290-0

Weiner RA, Weiner S, Pomhoff I, Jacobi C, Makarewicz W, Weigand G (2007) Laparoscopic sleevegastrectomy—influence of sleeve size and resected gastric volume. Obes Surg 17:1297–1305

Reinhold RB (1982) Critical analysis of long term weight loss following gastric bypass. Surg Gynecol Obstet 155(3):385–394

Levine MS, Carucci LR (2014) Imaging of bariatric surgery: normal anatomy and postoperative complications. Radiology 270(2):327–341

Pagé MP, Kastenmeier A, Goldblatt M, Frelich M, Bosler M, Wallace J, Gould J (2014) Medically refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease in the obese: what is the best surgical approach? Surg Endosc. doi:10.1007/s00464-013-3343-3

Lazoura O, Zacharoulis D, Triantafyllidis G, Fanariotis M, Sioka E, Papamargaritis D, Tzovaras G (2011) Symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy are related to the final shape of the sleeve as depicted by radiology. Obes Surg 21:295–299

Triantafyllidis G, Lazoura O, Sioka E, Tzovaras G, Antoniou A, Vassiou K, Zacharoulis D (2011) Anatomy and complications following laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: radiological evaluation and imaging pitfalls. Obes Surg 21(4):473–478

Vidal P, Ramón JM, Busto M, Domínguez-Vega G, Goday A, Pera M, Grande L (2014) Residual gastric volume estimated with a new radiological volumetric model: relationship with weight loss after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg 24:359–363

Kleidi E, Theodorou D, Albanopoulos K, Menenakos E, Karvelis MA, Papailiou J, Stamou K, Zografos G, Katsaragakis S, Leandros E (2013) The effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy on the antireflux mechanism: can it be minimized? Surg Endosc. doi:10.1007/s00464-013-3083-4

Toro JP, Lin E, Patel AD, Davis SS Jr, Sanni A, Urrego HD (2014) Association of radiographic morphology with early gastroesophageal reflux disease and satiety control after sleeve gastrectomy. J Am Coll Surg 219(3):430–438

Melissas J, Koukouraki S, Askoxylakis J, Stathaki M, Daskalakis M, Perisinakis K, Karkavitsas N (2007) Sleeve gastrectomy: a restrictive procedure? Obes Surg 17(1):57–62

Gianos M, Abdemus A, Rosenthal RJ (2011) Understanding the mechanisms of action of sleeve gastrectomy on obesity. In: Third annual international consensus summit on sleeve gastrectomy

Gumbs AA, Gagner M, Dakin G, Pomp A (2007) Sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity. Obes Surg 17(7):962–969

Braghetto I, Cortes C, Herquiñigo D, Csendes P, Rojas A, Mushle M, Korn O, Valladares H, Csendes A, Maria Burgos A, Papapietro K (2009) Evaluation of the radiological gastric capacity and evolution of the BMI 2–3 years after sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg 19(9):1262–1269

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Giulio Barbiero, Giovanna Romanucci, Valeria Ortu, Monica Zuliani, Diego Miotto, Fabio Pomerri, Alice Albanese, Daunia Verdi, Luca Prevedello and Mirto Foletto declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barbiero, G., Romanucci, G., Ortu, V. et al. Relationship between gastric pouch and weight loss after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Endosc 30, 1559–1563 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4377-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4377-5