Abstract

Background

The use of self-gripping mesh during laparoscopic TEP inguinal hernia repairs may eliminate the need for any additional fixation, and thus reduce post-operative pain without the added concern for mesh migration. Long-term outcomes are not yet prospectively studied in a controlled fashion.

Methods

Under IRB approval, from January 2011–April 2013, 91 hernias were repaired laparoscopically with self-gripping mesh without additional fixation. Patients were followed for at least 1 year. Demographics and intraoperative data (defect location, size, and mesh deployment time) are recorded. VAS is used in the recovery room (RR) to score pain, and the Carolinas Comfort Scale ™ (CCS), a validated 0–5 pain/quality of life (QoL) score where a mean score of >1.0 means symptomatic pain, is employed at 2 weeks and at 1 year. Morbidities, narcotic usage, days to full activity and return to work, and CCS scores are reported.

Results

Sixty two patients, with 91 hernias repaired with self-gripping mesh, completed follow-up at a mean time period of 14.8 months. Seventeen hernias were direct defects (average size 3.0 cm). Mesh deployment time was 193.7 s. RR pain was 1.1/10 using a VAS. Total average oxycodone/acetaminophen (5 mg/325 mg) usage = 5.0 tablets, days to full activity was 1.6, and return to work was 4.2 days. Thirteen small asymptomatic seromas were palpated without any recurrences or groin tenderness, and all seromas resolved by the 6 month visit. Transient testis discomfort was reported in five patients. Urinary retention was 3.2 %. Mean CCS™ scores at the first visit for groin pain laying, bending, sitting, walking, and step-climbing were 0.2, 0.5, 0.4, 0.3, and 0.3, respectively. At the first post op visit, 4.8 % had symptomatic pain (CCS > 1). At 14.8 months, no patients reported symptomatic pain with CCS scores for all 62 patients averaging 0.02, (range 0–0.43). There are no recurrences thus far.

Conclusions

Self-gripping mesh can be safely used during laparoscopic TEP inguinal hernia repairs; our cohort had a rapid recovery, and at the 1-year follow-up visit, there were no recurrences and no patients reported any chronic pain as defined by a CCS™ > 1.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Inguinal hernia repairs are common procedures in general surgery, with roughly 800,000 performed annually in the United States [1]. In a paper published in 2003, it was stated that approximately 15 % of these repairs are performed laparoscopically, by either the total extraperitoneal (TEP) or transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) technique; this number has likely risen since that paper’s publication [1]. Irrespective of technique, the incidence of post-operative chronic groin pain after an inguinal hernia repair remains at an average of 5–10 %, translating into approximately 40,000–80,000 new cases of inguinodynia each year [2]. Minimizing post-operative acute and chronic groin pain without increasing recurrence rates have become paramount and can be accomplished by optimizing dissection techniques, eliminating nerve trauma, reducing recurrence rates, as well as by minimizing the use of mesh fixation devices when avoidable [3, 4].

Self-adhering or self-gripping mesh materials have been developed to potentially reduce the risk of the chronic pain that is associated with the use of suture or tack fixation [5, 6]. Rigorous studies have already shown that self-gripping mesh material (Progrip™, Covidien, New Haven, CT) is associated with less pain in the early recovery period when used during an open Lichtenstein repair [7]. Randomized prospective trials (RPT) show that the longer-term pain is not significantly different, and more importantly there are also no differences in recurrence rates after the mesh is used in open inguinal hernia repairs [8]. The use of self-gripping mesh during laparoscopic TAPP repairs has been reported; however, short and long-term outcomes have not yet been evaluated following the use of the same self-gripping mesh during laparoscopic TEP inguinal hernia repairs.

The primary purpose of our study was to prospectively follow patients’ immediate and 1-year pain and quality of life scores following a TEP repair with Progrip™ mesh without any additional mesh fixation. Secondary outcomes included establishing feasibility of inserting the mesh during a TEP repair, intraoperative morbidity rates, and 1-year recurrence rates. To evaluate pain and QoL, we employed the Carolinas Comfort Scale™ (CCS™), a validated post hernia quality of life and pain assessment tool [9].

Methods

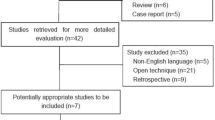

With Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, from January 2011–April 2013, 91 hernias were repaired laparoscopically in 62 patients by the TEP technique with self-gripping mesh and no additional fixation. To be included in this study, patients had to be willing to provide informed consent when the study was reviewed with them in the office. Exclusion criteria included poor working space visibility discovered intraoperatively and the usage of tacks to implicate the direct hernia sac. Informed consent was obtained in the office. A secure prospective database was created and maintained, and a retrospective analysis of this data was then performed for the purpose of this study. Preoperative data collection included patient demographics, hernia laterality and type, and whether the hernia was a recurrence or primary (Table 1). Information was also obtained as to comorbid conditions, smoking status, and previous surgeries (Table 2).

Intraoperative data included hernia location, size (cm), time (seconds) to deploy the mesh (from insertion to final position), intraoperative complications, total operative times, and immediate post-operative pain scores (0–10 VAS). All mesh placements were performed by a single surgeon (BPJ).

Post-operative data at the 1st follow-up visit included total narcotic usage (number of tablets), return to normal activity (days), return to work (days), morbidities, recurrence rates, and assessment of pain and quality of life utilizing the Carolinas Comfort Scale™ (CCS™) (Table 3). Return to normal activity was assessed by asking patients, at their first post-operative visit, when they could ambulate and get in and out of bed without issues. Similarly, patients were asked when they returned to their occupation if applicable, and this was used to determine time to return to work. Repeat CCS™ questionnaires were completed and presence of recurrence was also completed at the 1-year follow-up. To determine the CCS™ scores, average scores of all test measures for each patient were calculated. A mean CCS™ score > 1 was considered symptomatic, as defined by Belyansky et al. [4].

Prosthetic mesh

Parietex ProGrip™ mesh is a lightweight, self-gripping mesh composed of monofilament polyester and polylactic acid (PLA) microgrips indicated for inguinal hernia repair. It is an isoelastic large-pore knitted fabric with a density of 75 g/m2 at implantation and 38 g/m2 after microgrip absorption. The resorbable microgrips provide immediate adherence to surrounding muscle and adipose tissue during the initial days post hernia surgery, serving as an alternate method of fixation to traditional sutures, tacks, staples, or fibrin sealants, all mechanisms which can penetrate underlying tissue and potentially damage surrounding nerves.

Operative technique and self-gripping mesh placement

A standard three trocar technique is used, with the placement of a Hasson trocar at the infraumbilical location after a balloon spacemaker is used to help create the extraperitoneal space, followed by placement of an additional two 5-mm trocars in the midline between the umbilicus and pubic bone. A 10-mm 45° angled scope is used. Dissection is begun in the midline to identify Cooper’s ligament and the pubic symphysis. Dissection is then carried out laterally to the level of the anterior superior iliac spine to expose the hernia sac, transversalis fascia, cord structures, and epigastric vessels. Once the peritoneal sac is identified and the hernia reduced, inspection is done to look for hernias at all potential sites (direct, indirect, and femoral). Our routine practice is to look for a contralateral hernia, and repair these if discovered intraoperatively.

Each hernia defect is measured (in cm) and the diameter recorded in the spreadsheet. After hemostasis is confirmed, a 15 × 15 cm Parietex Progrip™ self-gripping mesh is trimmed to a 15 × 11 cm2 rectangle and then the corners are rounded (Fig. 1). To insert the mesh, the material is folded loosely in thirds, and inserted through the Hasson trocar and into the extraperitoneal working space with deployment and manipulation of the mesh within the myopectineal orifice to cover all potential hernia sites. For the patients in this study, the medial edge of the mesh was aligned with the midline, and the mesh was unfolded in a medial to lateral direction. After this study, the author now prefers to fold and unfold the mesh in a “top down” configuration as opposed to medial to lateral. No additional tacks, staples, sutures, or fibrin sealant is used. In each case, attention is focused to assure there was adequate peritoneum reduction below the inferior edge of the mesh, such that the inferior edge of the mesh lay flat against the retroperitoneum. Once the CO2 has been evacuated and trocars removed, the fascia and incisions are closed.

Results

From January 2011–April 2013, a total of 91 hernias were repaired in 62 patients by a laparoscopic TEP with placement of self-gripping mesh without any additional tack fixation. There were no conversions. Ten patients who were intended to receive Progrip mesh bilaterally were excluded due to poor working space visibility on one side; insertion of Progrip was never attempted on that side for these patients, and they were not included in the study. One patient was excluded because a tack was used to implicate the direct hernia sac, and we did not want the presence of a tack even though it was not used for mesh fixation.

The procedures included 29 bilateral hernia repairs and 33 unilateral repairs. The intraoperative findings included 17 direct (mean defect size 3.0 cm) defects, 61 indirect defects, 6 Pantaloon (both indirect and direct) defects, and 2 femoral defects.

Patient demographics are displayed in Table 1. The study population was 88.7 % male, with an average age of 43.8 (range 17–74) and average BMI 25.8 (range 18.0–39.7). Comorbid data are displayed in Table 2. Five patients (8.1 %) were current smokers, and 19 patients (30.6 %) had at least one co-morbidity, the most common being hypertension (seven patients).

The operative time averaged 66 min (incision to final dressing), with a mean mesh deployment time of 193.7s. (Figure 2). All mesh was inserted without incident, and we only encountered one intraoperative morbidity which included a patient who became bradycardic during the balloon spacemaker inflation portion of the procedure. The bradycardia was responsive to atropine and desufflation, and the case was completed without further incident.

In the recovery room, immediate post-operative pain was low with a mean VAS score of 1.1. Two patients (3.2 %) experienced urinary retention requiring a temporary foley catheter. The mean time to the initial post-operative follow-up visit was 2.5 weeks, and the average number of narcotic tablets required during that time was 5.0. Mean time to return to full activities and to return to work was 1.6 and 4.2 days, respectively. On a thorough initial post-operative exam, even if not noticed by the patient, 13 seromas (13.2 % of hernias) were appreciated. Each was asymptomatic and spontaneously resolved prior to 6-month and 1-year assessment. Five patients (9.1 % of males) reported temporary testis discomfort, all of which resolved prior to the 6-month follow-up visit.

Regarding pain and quality of life, 3 of the 62 patients (4.8 %) at the initial post-operative visit had mean CCS scores > 1. No patients at the 1-year follow-up reported a mean CCS™ score > 1. At the first post op visit, the mean CCS™ score was 0.25 (range 0–1.35), while at the 1-year visit the average CCS score was 0.02 (range 0–0.43) (Fig. 3). At the one-year visit, there were no recurrences, no chronic pains reported, and no long-term seromas for any of the patients in this cohort.

Discussion

Chronic groin pain, or inguinodynia, after a laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair remains a potential complication of both TEP and TAPP procedures. The ability for surgeons to minimize the incidence of chronic pain has potential implications for thousands of patients who undergo laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs each year. Causes of acute and chronic pain after hernia surgery can be related to a number of factors including dissection technique, seromas and hematomas, vas deferens trauma, fixation devices, mesh material, incomplete dissections, and hernia recurrences. The multifactorial etiology of post-operative hernia pain adds complexity and expense to the work-up and management of inguinodynia, and so efforts must continue to focus on optimizing products and surgeon’s ability to prevent avoidable post-operative pain and recurrences.

Along these lines, there is a strong need for an implantable mesh product that can be used during laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs that have immediate adhesive properties to reduce the risk of early mesh migration and recurrence, while simultaneously eliminating the post-operative pain potentially caused by excessive use of sutures and tacks. Especially during a laparoscopic repair where fixation devices cannot be placed below the level of the ileopubic tract, there will remain a risk of mesh migration without fixation in some patients [10]. Both absorbable and permanent fixation tacks have been blamed for acute and chronic pain syndromes, and excessive use of tacks has been shown to increase the risk of chronic pain [4]. As an alternative, the use of fibrin glue (or sealant) has gained popularity as a method of mesh fixation, but has been criticized for its added expense. Interestingly, in some studies, fibrin sealant (FS) has actually been shown to be more cost effective than the use of tacks, although its cost is still more than using no additional fixation method at all [11]. In a randomized prospective trial, Melissa et al. showed that the use of mechanical staples is more expensive than fibrin sealant with a mean cost of 347 versus 167 dollars, respectively [12]. To date, however, the use of FS during laparoscopic TEP and TAPP has not yet penetrated well.

Progrip™ mesh (Covidien, New Haven, CT, USA), originally invented by an open inguinal hernia surgeon from France named Dr. Philippe Chastan, is a novel hernia mesh product that is immediately self-gripping, without needing to add fixation devices or glues. It has the advantage of being made of monofilament polypropylene woven with an absorbable polylactic acid (PLA) microfiber that act as microgrips. The mesh has a pore size of 1.1–1.7 mm, with a weight of 82 g/m2 before PLA resorption and a weight of 41 g/m2 after PLA resorption. The grips provide immediate and strong fixation to the muscles and adipose soft tissues, while the mesh is much less immediately adherent to periosteum, peritoneum, ligaments, and fascia.

There is already vast experience with the mesh. Hollinsky et al. showed that at 5 days post-operatively, the self-gripping mesh had superior adherence strength than unfixed mesh and mesh fixed with fibrin glue, and had equivalent adherent strength as mesh fixed with a stapler device [13]. To follow, Kapischke showed there was a 29 % reduction in pain medication requirements when no sutures and Progrip™ were used during an open Lichtenstein repair compared to a traditional open Lichtenstein repair with sutures [14]. Several studies evaluating the self-gripping mesh in open and laparoscopic TAPP repairs have shown the benefit of minimal post hernia recurrences and minimal chronic pain [15, 16]. A large randomized prospective trial has confirmed the early benefits of this mesh without additional suture fixation during an open Lichtenstein repair [7]. In our practice, we mainly perform a laparoscopic TEP hernia repair, and because of these promising results, we elected to begin using Progrip™ for our cases. At the time, no study to date had evaluated the quality of life with the CCS™ scores following a laparoscopic TEP with this self-gripping mesh.

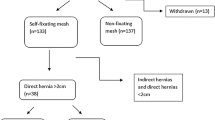

When we first transitioned in February 2010 from using a heavyweight polypropylene with tacks to a lightweight polyester with absorbable microgrips without tacks during a laparoscopic TEP inguinal hernia repair, we initially studied our patient’s pain complaints using a VAS score sheet in the recovery room and at the first 2-week post-operative visit. We had three different groups of patients as our transition progressed (Fig. 4): those done with a heavyweight small pore polypropylene and permanent tacks, those done with Progrip™ and tacks, and then those done with Progrip™ without any tacks. These early results over the transition period, as demonstrated in Fig. 4, showed possible less perceived pain when no tacks were used. For this reason, we decided to perform this more formal prospective study to evaluate feasibility, pain, and quality of life.

Our current prospective study has shown that patients who were 2-week post-TEP repair with self-gripping mesh had CCS™ scores averaging 0.25, with 4.8 % of patients having CCS™ > 1. For comparison, a large volume review of the International Hernia Mesh Registry showed that at 1-month follow-up after TEP for unilateral primary hernias, 8.9 % of patients had a CCS™ score > 1, and that number rose to 16.9 % if the patients had a bilateral repair [4]. These CCS™ values suggest that the patients in our study have done favorably. Our patients experienced an average pain score (on 1–10 scale) of 1.1 post-operatively, and had an average requirement of five percocet tablets, with an average return to full activity and return to work in 1.6 and 4.2 days, respectively. For comparison, a paper by Khoury including 150 inguinal hernia patients repaired with TEP reported an average of four tablets of acetaminophen + codeine, post-operative pain score average of three, and average time to return to work of 8 days for these patients [17]. Our rapid recovery in this cohort is likely due to a number of factors including patient selection, surgeon experience, and technique.

We did notice a moderate rate of seroma and testis discomfort, but all of these patients had resolution of their symptoms by their 1-year follow-up, and we attributed these findings in part to our dissection technique. Of note, the sermoa rate of 13.2 % observed in this cohort is less than previously reported results for laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs; a RPT comparing outcomes of TEP and TAPP repairs found 32.5 % seroma incidence in TEP repairs and 16.2 % in TAPP repairs at 7 days post op [18]. None of the 62 patients in our cohort had a CCS™ > 1 at 1 year, suggesting that the mesh is safe to use without chronic issues.

The self-gripping mesh we used can adhere to itself if rolled too tightly, and thus the mesh has been criticized for being difficult to handle. While this characteristic is true when attempting to insert the mesh in a small or inadequate space, we found that if the preperitoneal space is adequately made, the insertion and unfolding of the mesh is more straightforward once past the learning curve of how to handle the mesh. In fact, ten patients whom we had planned to enroll in this study had small working spaces and we elected to not use the self-gripping mesh for these patients.

It is important to also fold the mesh in thirds, and not simply roll it up. Blending a folding (not rolling) method with a large working space permits easier handling. A surgeon can decide if unfolding the mesh top down or from medial to lateral is beneficial in their own hands. During this study, we unrolled medial to lateral. We have since changed to unrolling it top down, and find this method to be the simplest.

We performed an additional analysis of our mesh deployment time during our laparoscopic TEP repairs. For the 91 hernia repairs, our average time from insertion of mesh to complete deployment and placement was 193.7 s. As shown in Fig. 2, there is a learning curve of approximately ten cases to see a significant decrease in mesh insertion time. In this study, we inserted all mesh by unrolling in a medial to lateral direction. We now unroll the mesh from the top down, and find this to add additional speed to the deployment time.

Critiques of our study include that it is a single-arm cohort, with lack of a control group to directly compare CCS™ scores of non-self-gripping mesh to self-gripping mesh. However, given that many studies have published data on the outcomes of laparoscopic TEP inguinal hernia repairs with non-self-gripping mesh, there is still a solid foundation of data for evaluating differences between the two types of mesh, even if it is not a direct and controlled comparison. That being said, our CCS scores and recurrence rates compare favorably to previous published results [4].

Despite the limitations of this study, we have successfully shown that Progrip™ mesh can be inserted without complications during a laparoscopic TEP inguinal hernia repair. Patients in this cohort have a rapid recovery with very low CCS™ scores both at the first follow-up visit and again at the 1-year point. Seroma and transient testicular discomfort were the two most frequent post op findings in this cohort, but both of these resolved spontaneously and in our opinion are likely consequent to having a TEP repair, and not directly related to the mesh product. None of the patients in this cohort have had a recurrence, including those who presented with direct defects with an average diameter of 3.0 cm.

Conclusions

The insertion of self-gripping mesh without the use of any additional fixation during a laparoscopic TEP inguinal hernia repair is feasible and safe and is associated with very low pain scores in the immediate post-operative period as well as for at least 1 year afterward. Our cohort had a rapid recovery, quick return to work, and low CCS™ scores. At the 1-year follow-up visit, there were no recurrences and no patients reported any chronic pain as defined by a CCS™ > 1.

References

Rotkow IM (2003) Demographic and socioeconomic aspects of hernia repair in the United States in 2003. Surg Clin N Am 83(5):1045–1051 v–vi

Simons MP (2009) European hernia society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia 13:343–403

Taylor C et al (2008) Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair without mesh fixation, early results of a large randomised clinical trial. Surg Endosc 22(3):757–762

Belyansky I, Tsirline VB, Klima DA, Walters AL, Lincourt AE, Heniford TB (2011) Prospective, comparative study of postoperative quality of life in TEP, TAPP, and modified Lichtenstein repairs. Ann Surg 254(5):709–715

Kosai N, Sutton PA, Evans J, Varghese J (2011) Laparoscopic preperitoneal mesh repair using a novel self-adhesive mesh. J Minimal Access Surg 7(3):192–194

Kingsnorth A, Nienhuijs S, Schüle S, Appel P, Ziprin P, Eklund A, Smeds S (2010) Preliminary results of a comparative randomized study: benefit of self-gripping Parietex Progrip™ mesh. Hernia 14:0–001

Kingsnorth A (2012) Randomized controlled multicenter international clinical trial of self-gripping Parietex Progrip polyester mesh versus lightweight polypropylene mesh in open inguinal hernia repair: interim results at 3 months. Hernia 16(3):287–294

Chastan P (2009) Tension-free open hernia repair using an innovative self-gripping semi-resorbable mesh. Hernia 13(2):137–142

Heniford T, Walters AL, Lincourt AE, Novitsky YW, Hope WW, Kercher KW (2008) Comparison of generic versus specific quality-of-life scales for mesh hernia repairs. J Am Coll Surg 206(4):638–644

Lowham AS, Filipi CJ, Fitzgibbons RJ Jr, Stoppa R, Wantz GE, Felix EL, Crafton WB (1997) Mechanisms of hernia recurrence after preperitoneal mesh repair. Traditional and laparoscopic. Ann Surg 225(4):422

Ng WT, Auyeung K (2008) An inexpensive and effective technique for hernioplasty mesh anchorage. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutaneous Tech 18(2):228–229

Melissa CS, Bun TA, Wing CK, Chung TY, Wai NE, Tat LH (2013) Randomized double-blinded prospective trial of fibrin sealant spray versus mechanical stapling in laparoscopic total extraperitoneal hernioplasty. Ann Surg 259(3):432–437

Hollinsky C et al (2009) Comparison of a new self-gripping mesh with other fixation methods for laparoscopic hernia repair in a rat model. JACS 208(6):1–1107

Kapischke M, Schulze H, Caliebe A (2010) Self-fixating mesh for the Lichtenstein procedure—a prestudy. Langenbecks Arch Surg 395(4):317–322

Fumagalli RU, Puccetti F, Elmore U, Massaron S, Rosati R (2013) Self-gripping mesh versus staple fixation in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: a prospective comparison. Surg Endosc 5:1798–1802

Birk D, Hess S, Garcia-Pardo C (2013) Low recurrence rate and low chronic pain associated with inguinal hernia repair by laparoscopic placement of Parietex ProGrip™ mesh: clinical outcomes of 220 hernias with mean follow-up at 23 months. Hernia 17(3):313–320

Khoury N (1998) A randomized prospective controlled trial of laparoscopic extraperitoneal hernia repair and mesh-plug hernioplasty: a study of 315 cases. J Laparosc Adv Surg Tech 8(6):367–372

Kumar Bansal V et al (2013) A prospective, randomized comparison of long-term outcomes: chronic groin pain and quality of life following totally extraperitoneal (TEP) and transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) laparoscopic inguinal hernia dfrepair. Surg Endosc 27:2373–2382

Disclosures

Dr. Brian Jacob provides consulting services for Covidien (New Haven, CT). Bresnahan Erin, Bates Andrew, Wu Andrew, Reiner Mark and Jacob Brian have financial interests to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bresnahan, E., Bates, A., Wu, A. et al. The use of self-gripping (Progrip™) mesh during laparoscopic total extraperitoneal (TEP) inguinal hernia repair: a prospective feasibility and long-term outcomes study. Surg Endosc 29, 2690–2696 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3991-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3991-y