Abstract

Background

Trocar-associated visceral injuries are rare but potentially fatal complications of laparoscopic access. More commonly, abdominal wall bleeding occurs, which usually requires hemostatic measures and prolongs operative time. Blunt-tipped trocars have been postulated to carry a lower risk of abdominal wall bleeding and intra-abdominal injuries. The aim of the present systematic review and meta-analysis was to comparatively evaluate the relative risks of abdominal wall bleeding, visceral injuries, and overall complications with the use of bladed and blunt-tipped laparoscopic trocars.

Methods

The databases of Medline, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Randomized Trials were searched to identify randomized studies that compared trocar-associated complications with the use of blunt and bladed trocars. Primary outcome measure was the relative risk of abdominal wall trocar site bleeding, and secondary outcome measures included visceral injuries and overall complications. Outcome data were pooled and combined overall effect sizes were calculated using the fixed- or random-effects model.

Results

Eight eligible randomized trials were identified; they included 720 patients with a median Jadad score of 4. The incidence of abdominal wall bleeding for the blunt and the bladed trocar group was 3 and 9 %, respectively [odds ratio (OR) 0.42, 95 % confidence interval (CI) 0.21–0.88]. Trocar-associated morbidity rate, excluding bleeding events of the abdominal wall, was documented at 0.2 and 0.7 % of the blunt and the bladed trocar arm, respectively (OR 0.43, 95 % CI 0.06–2.97). The overall trocar-associated morbidity rate was 3 % in the blunt trocar group and 10 % in the bladed trocar group (OR 0.38, 95 % CI 0.19–0.77).

Conclusions

Reliable data support a lower relative risk of trocar site bleeding and overall complications with blunt laparoscopic cannulas than bladed trocars. Transition to blunt trocars for secondary cannulation of the abdominal wall is thus strongly recommended. Larger patient populations are required to estimate the relative risk of visceral injuries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Establishment of pneumoperitoneum and cannulation of the abdominal cavity are the first steps of diagnostic and operative laparoscopy. Although rare, trocar-associated injuries result in significant morbidity and may be fatal in case of laceration of major abdominal vessels or bowel lesions [1, 2]. More frequently, vascular injuries of the abdominal wall occur [3], which prolong operative time and often require hemostatic measures such as cauterization and transabdominal suturing [4, 5]. The epigastric artery and its branches are perhaps the most frequently injured vessels during trocar insertion. Failure to identify the vascular injury during or after completion of surgery may result in significant blood loss and hypovolemic shock [6].

Although surgical technique in some part may account for adverse trocar-associated events, the type of trocar used has been postulated to influence the incidence of vascular and visceral injuries [2]. There are currently two types of disposable trocars available on the market based on the design of the cannula tip. Cutting or bladed trocars represent the first generation of laparoscopic ports and may have one or two crossed sharp blades or a sharp cone-shaped crown. This configuration facilitates cutting of the abdominal wall layers and entrance into the peritoneal cavity without significant force, provided the skin incision is much larger than the diameter of the cannula [7]. The second generation of trocars was designed with a blunt tip in order to allow gentle penetration of the abdominal wall, with the potential advantage of lower risk of vascular wall and visceral injuries [8], and early reports have linked the use of blunt-tipped trocars with a reduction of postoperative pain [9]. Indeed, the blunt configuration of the tip of the port allows dissection rather than division of muscle fibers of the abdominal wall musculature, thereby potentially sparing neural damage.

In view of the low but substantial risk of trocar-related complications and the high volume of laparoscopic procedures performed around the world, choosing the type of trocar with the highest safety index should be based on high-quality clinical evidence. The present systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials was conducted to comparatively evaluate the relative risks of abdominal wall bleeding, visceral injuries, and overall complications with the use of bladed and blunt-tipped laparoscopic trocars.

Methods

Eligibility criteria and outcome measures

A protocol determining the inclusion criteria and methods of analysis was designed in advance. Randomized controlled trials that compared the clinical use of blunt and bladed trocars were considered for inclusion. Reports were considered eligible if they included trocar-associated complications as a primary or secondary outcome measure in the setting of gynecologic, urologic, or general laparoscopic surgery. Experimental studies performed on animals were excluded from the present analysis. No date or language restrictions were applied, and articles published in a language other than English were translated.

The primary outcome measure of this meta-analysis was the relative risk of abdominal wall bleeding following blunt or bladed trocar insertion, and secondary outcome measures were the risk of visceral or vascular abdominal injuries and overall trocar-associated morbidity.

Sources, literature search, and eligibility assessment

The electronic databases of the National Library of Medicine (Medline, provider Ovid, from 1966 to August 2012), Excerpta Medica (EMBASE, provider Elsevier, from 1980 to August 2012), and the Cochrane Central Register of Randomized Trials were searched for relevant articles. The Medical Subject Headings “laparoscopy” and “trocar”, combined with the terms “cutting” or “bladed” or “dilating” or “blunt” or “expanding” or “radial”, were used. The titles and abstracts of extracted records were scrutinized; articles that were considered to fulfill the eligibility criteria were retrieved for full-text review. In a second-level search, the reference lists of included articles were checked to find potentially eligible studies. Reports of congresses or scientific meetings included in peer-reviewed journals and indexed in the above databases were also scrutinized. The literature search and the eligibility assessment were performed by two independent authors (SAA and GAA). Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus. The last search was run on August 1, 2012. A manual update search of the Medline database using the additional terms “access” or “complication” or “injury” was undertaken upon completion of the study, the last search having been run on January 1, 2013.

Extraction of data

Data of interest were extracted from the text, tables, and figures and were indexed in an ad hoc developed electronic file. One study author extracted the study data and a second author checked their accuracy. The following data were collected from each study: year of publication, country of origin, period of treatment, number of participating centers, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, type of surgery, and primary and secondary outcome measures. Demographic characteristics of the study populations were collected: number of patients randomized, number of patients included in the analysis, number of patients allocated in the blunt trocar group, number of patients allocated in the bladed trocar group, male-to-female ratio, mean age, and mean body mass index (BMI). To assess the methodological quality, the following questions were addressed for each trial: whether the study was randomized, whether the randomization method was reported, whether the method of randomization was correct, whether the study was double-blinded, whether the blinding method was appropriate, and whether there were dropouts or withdrawals from the trial. The following outcome data were collected from each study arm of individual trials: trocar site bleeding at the time of surgery, trocar-associated complications other than bleeding, and type of complication. Risk of study bias was assessed by two study authors in an nonblinded manner.

Quality assessment and methods of analysis

Assessment of methodological quality was performed using the Jadad score [10]. This scoring system takes into account the randomization process, the blind assessment of investigated treatments, and reporting of withdrawals or dropouts. The minimum score of 1 indicates poor methodological quality and the maximum score of 5 suggests excellent methodological quality.

Study-specific estimates were combined using random-effects or fixed-effects models as appropriate. Pooled odds ratios (OR) with 95 % confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to measure the effect of each type of procedure on categorical variables. Heterogeneity among the trials was assessed using I 2 statistics. Publication bias was assessed using Egger’s regression intercept. Statistical analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta Analysis ver. 2.0 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ). Statistical expertise was provided by one of the study authors (GAA). The present meta-analysis conformed to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement standards, a methodological protocol with items regarded essential for transparent reporting [11].

Results

Search results and study selection

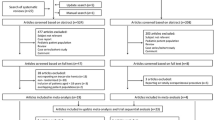

Our search of the databases identified 262 results and 189 unique records, after electronically generated and manual exclusion of duplicate records. Some 181 articles were discarded as review articles (n = 11), letters, comments, editorials, or technical notes (n = 5), nonrandomized studies (n = 18), animal studies (n = 6), and articles of irrelevant subject matter (n = 141). Eight randomized controlled trials were identified [12–19]. After full text review, one article was excluded because outcome data were insufficiently provided, more specifically, patient allocation was unclear [12]. The second-level manual search of the reference lists identified another eligible study [20]. Finally, a total of eight randomized trials entered the meta-analytical model (Fig. 1) [13–20]. The updated search upon completion of the study identified a total of 112 additional records but no additional eligible randomized trials were identified.

Study characteristics

The study population consisted of 720 patients (Table 1). The blunt trocar group enrolled 289 patients and the bladed trocar group enrolled 303 patients, and two studies with a total of 128 patients were self-controlled [15, 16], i.e., a cutting and a blunt trocar were randomly inserted symmetrically on each side of the abdominal wall. Year of publication ranged between 2000 and 2007. Five studies were single-center trials [13–16, 18], two studies enrolled patients from two institutions [19, 20], and one was a multi-institutional study [17]. Inclusion criteria greatly depended on the surgical discipline, and adult patients were commonly considered for inclusion. A significant variation in exclusion criteria was recorded: three studies did not consider patients with acute inflammatory abdominal pathology with the objective of evaluating postoperative pain [17–19]. Six trials were of satisfactory to excellent methodological quality (Jadad score 3–5) [13–17, 19], and two studies reached a Jadad score of 2 [18, 20] because they failed to report the method of randomization or blinding method, although one of the two studies was reportedly double-blinded (Table 2) [20].

A summary of the characteristics of the study populations is presented in Table 3. Mean or median age and BMI were inconsistently reported across studies, and male-to-female ratio depended on the surgical discipline involved in the trial (gynecologic or general surgery). The study population of each trial ranged between 30 and 244 patients. The majority of studies considered postoperative pain the primary outcome measure and trocar-related complications the secondary outcome measure. All studies reported on data that address the primary and secondary outcome measures of the present analysis. Table 4

Synthesis of results and outcome

Abdominal wall bleeding Significant injury of the abdominal wall vasculature was reported for 13 of 417 patients (3 %) of the blunt trocar group and for 38 of 431 patients (9 %) of the bladed trocar group (OR 0.42, 95 % CI 0.21–0.88, P = 0.020; Fig. 2). There was no evidence of between-study heterogeneity (I 2 ~ 0 %), and evidence of publication bias was insignificant (P = 0.068; Fig. 3).

Funnel plot assessing the data on the incidence of trocar-associated abdominal wall bleeding presented in Fig. 2

Major complications Trocar-associated morbidity, excluding bleeding events from the abdominal wall, was documented for 1 of 417 patients (0.2 %) of the blunt trocar arm and for 3 of 431 patients (0.7 %) of the bladed trocar arm (Fig. 4) (OR 0.43, 95 % CI 0.06–2.97; P = 0.392). There was no evidence of between-study heterogeneity (I 2 ~ 0%).

Overall complications Morbidity rates were 14/417 (3 %) and 41/431 (10 %) in the blunt and the bladed trocar group, respectively (OR 0.38, 95 % CI 0.19 0.77; P = 0.007; Fig. 5, Table 4). There was no evidence of between-study heterogeneity (I 2 ~ 0%; P = 0.437) or publication bias (P = 0.149; Fig. 6).

Funnel plot assessing the data on overall complications presented in Fig. 5

Discussion

Our meta-analytical model has demonstrated a greater risk of abdominal wall bleeding and overall trocar-associated complications with the use of blunt cannulas. However, no significant differences were demonstrated with regard to visceral or abdominal vascular injuries between the two study groups. Such complications occurred in only two studies [17, 20] and were more frequently encountered in the bladed trocar group. It may be suggested that the total number of patients was limited and the incidence of intra-abdominal injuries was low, which prevents detection of statistically significant differences between the two study groups. The hypothesis of a greater risk for major morbidity with the use of bladed trocars cannot be supported from the present analysis.

A limitation of our analysis may be the variety of bladed trocar systems involved. The majority of studies reported the manufacturer and the number of blades, although the absence of a shielding system for protecting abdominal viscera was reported by one study only [15]. Whereas shielded trocars may not be less harmful to the abdominal wall, nonshielded devices may carry a higher risk of causing intra-abdominal injuries [16]. The relative effect of each type of trocar on visceral injuries therefore may be approached with caution. On the other hand, considerable homogeneity with regard to blunt trocars was documented, with six of the eight trials utilizing disposable, radially expanding cannulas [13, 16–19]. Assessment of the relative risk of abdominal wall bleeding is enhanced by the consistency of outcomes in favor of the blunt trocars. In spite of the variety of bladed trocar systems, the significantly higher risk of overall morbidity for cutting trocars may not be disregarded.

The power of the analysis is amplified by the good-to-excellent methodological quality of the majority of the reports, the low level of between-study heterogeneity, and the lack of evidence of publication bias. Nevertheless, the fact that the surgeons could not be blinded to the type of trocar used must be taken into account. Although patient and postoperative assessor blinding indicates methodological adequacy and quality of the reports, the inevitable lack of blinding of the surgeons might introduce surgical practice bias to some extent.

The present study did not evaluate the comparative risk of trocar-associated injuries during laparoscopic entry. Therefore, it must be pointed out that although the present data strongly suggest reduced morbidity for abdominal cannulation under visual control with blunt trocars, comparative evidence on morbidity following laparoscopic entry with either blunt or bladed trocars is scarce [1, 21]. Penetration of the abdominal wall with a blunt cannula may require a greater amount of force than a cutting cannula and thus potentially have a greater risk of injuring the major abdominal vessels [7]. Although rare, vascular complications following laparoscopic entry with blunt trocars have been reported [22, 23]. The striated cannula configuration of third-generation devices may result in a safer primary abdominal cannulation.

It has been suggested that blunt-tipped peritoneal access devices do not require fascial closure because the muscle fibers are dissected rather than cut [24]. A comparison of the incidence of trocar site hernia was not included in the present analysis for two reasons. First, incisional hernia may be considered a minor complication that does not contribute to significant patient morbidity. Furthermore, a proper comparative analysis of the risk of incisional hernia requires a respectable follow-up period, which among the studies was either short or inconsistently reported because incisional complications were considered an outcome variable in only two studies [16, 17]. Nevertheless, cases of incisional hernia following insertion of blunt trocars have been reported [4, 25]. Furthermore, the reported advantage of blunt over cutting trocars with regard to the amount of postoperative pain was not tested in the present analysis. Relevant data are currently contradictory [13, 15, 18, 26], and a systematic analytical approach of studies enrolling patients with various pathologies and acute peritoneal inflammation in terms of postoperative pain is challenging.

Conclusion

Strong evidence suggests a lower risk of abdominal wall bleeding and overall complications with blunt-tip trocars compared to bladed trocars. Transition to the routine use of blunt trocars for cannulation of the abdominal wall under laparoscopic vision is thus strongly recommended. A next step for future investigation would be the comparative evaluation of these trocar configurations with respect to the relative risk of major visceral and vascular abdominal injuries. Considering the rarity of these events, the conduction of a prospective multi-institutional trial is reasonable. Adequate reporting of adverse events during abdominal wall cannulation is considered necessary for constant improvement of instrumentation and for the development of safer peritoneal access devices.

References

Vilos GA, Ternamian A, Dempster J, Laberge PY, The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (2007) Laparoscopic entry: a review of techniques, technologies, and complications. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 29:433–465

Fuller J, Ashar BS, Carey-Corrado J (2005) Trocar-associated injuries and fatalities: an analysis of 1399 reports to the FDA. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 12:302–307

Opitz I, Gantert W, Giger U, Kocher T, Krähenbühl L (2005) Bleeding remains a major complication during laparoscopic surgery: analysis of the SALTS database. Langenbecks Arch Surg 390:128–133

Leibl BJ, Schmedt CG, Schwarz J, Kraft K, Bittner R (1999) Laparoscopic surgery complications associated with trocar tip design: review of literature and own results. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 9:135–140

Sileshi B, Achneck H, Ma L, Lawson JH (2010) Application of energy-based technologies and topical hemostatic agents in the management of surgical hemostasis. Vascular 18:197–204

Bhoyrul S, Vierra MA, Nezhat CR, Krummel TM, Way LW (2001) Trocar injuries in laparoscopic surgery. J Am Coll Surg 192:677–683

Tarnay CM, Glass KB, Munro MG (1999) Entry force and intra-abdominal pressure associated with six laparoscopic trocar-cannula systems: a randomized comparison. Obstet Gynecol 94:83–88

Bhoyrul S, Mori T, Way LW (1996) Radially expanding dilatation. A superior method of laparoscopic trocar access. Surg Endosc 10:775–778

Turner DJ (1996) A new, radially expanding access system for laparoscopic procedures versus conventional cannulas. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 3:609–615

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ (1996) Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 17:1–12

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 339:b2700

Venkatesh R, Sundaram CP, Figenshau RS, Yan Y, Andriole GL, Clayman RV, Landman J (2007) Prospective randomized comparison of cutting and dilating disposable trocars for access during laparoscopic renal surgery. JSLS 11:198–203

Bisgaard T, Jakobsen HL, Jacobsen B, Olsen SD, Rosenberg J (2007) Randomized clinical trial comparing radially expanding trocars with conventional cutting trocars for the effects on pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 21:2012–2016

Hamade AM, Issa ME, Haylett KR, Ammori BJ (2007) Fixity of ports to the abdominal wall during laparoscopic surgery: a randomized comparison of cutting versus blunt trocars. Surg Endosc 21:965–969

Stepanian AA, Winer WK, Isler CM, Lyons TL (2007) Comparative analysis of 5 mm trocars: dilating tip versus non-shielded bladed. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 14:176–183

Yim SF, Yuen PM (2001) Randomized double-masked comparison of radially expanding access device and conventional cutting tip trocar in laparoscopy. Obstet Gynecol 97:435–438

Bhoyrul S, Payne J, Steffes B, Swanstrom L, Way LW (2000) A randomized prospective study of radially expanding trocars in laparoscopic surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 4:392–397

Lam TY, Lee SW, So HS, Kwok SP (2000) Radially expanding trocar: a less painful alternative for laparoscopic surgery. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 10:269–273

Mettler L, Maher P (2000) Investigation of the effectiveness of the radially-expanding needle system, in contrast to the cutting trocar in enhancing patient recovery. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 9:397–401

Feste JR, Bojahr B, Turner DJ (2000) Randomized trial comparing a radially expandable needle system with cutting trocars. JSLS 4:11–15

Krishnakumar S, Tambe P (2009) Entry complications in laparoscopic surgery. J Gynecol Endosc Surg 1:4–11

Orvieto M, Breyer B, Sokoloff M, Shalhav AH (2004) Aortic injury during initial blunt trocar laparoscopic access for renal surgery. J Urol 171:349–350

Voitk A, Rizoli S (2001) Blunt hasson trocar injury: long intra-abdominal trocar and lean patient–a dangerous combination. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 11:259–262

Munro MG, Tarnay CM (2004) The impact of trocar-cannula design and simulated operative manipulation on incisional characteristics: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol 103:681–685

Kouba EJ, Hubbard JS, Wallen E, Pruthi RS (2007) Incisional hernia in a 12 mm non-bladed trocar site following laparoscopic nephrectomy. Urol Int 79:276–279

Mordecai SC, Warren OW, Warren SJ (2012) Radially expanding laparoscopic trocar ports significantly reduce postoperative pain in all age groups. Surg Endosc 26:843–846

Disclosures

Drs. Stavros A. Antoniou, George A. Antoniou, Oliver O. Koch, Rudolph Pointner, and Frank A. Granderath have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Antoniou, S.A., Antoniou, G.A., Koch, O.O. et al. Blunt versus bladed trocars in laparoscopic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Surg Endosc 27, 2312–2320 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-013-2793-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-013-2793-y