Abstract

Background

Although laparoscopic fundoplication effectively alleviates gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in the great majority of patients, some patients remain dissatisfied after the operation. This study was undertaken to report the outcomes of these patients and to determine the causes of dissatisfaction after laparoscopic fundoplication.

Methods

All patients undergoing laparoscopic fundoplication in the authors’ series from 1992 to 2010 were evaluated for frequency and severity of symptoms before and after laparoscopic fundoplication, and their experiences were graded from “very satisfying” to “very unsatisfying.” Objective outcomes were determined by endoscopy, barium swallow, and pH monitoring. Primary complaints were derived from postoperative surveys. Median data are reported.

Results

Of the 1,063 patients undergoing laparoscopic fundoplication, 101 patients reported dissatisfaction after the procedure. The follow-up period was 33 months. The dissatisfied patients (n = 101) were more likely than the satisfied patients to have postoperative complications (9 vs 4 %; p < 0.05) and to have undergone a prior fundoplication (22 vs 11 %; p < 0.05). For the dissatisfied patients, heartburn decreased in frequency and severity after fundoplication (p < 0.05) but remained notable. Also for the dissatisfied patients, new symptoms (gas bloat/dysphagia) were the most prominent postoperative complaint (59 %), followed by symptom recurrence (23 %), symptom persistence (4 %), and the overall experience (14 %). Primary complaints of new symptoms were most common within the first year of follow-up assessment and less frequent thereafter. Primary complaints of recurrent symptoms generally occurred more than 1 year after fundoplication.

Conclusions

Dissatisfaction is uncommon after laparoscopic fundoplication. New symptoms, such as dysphagia and gas/bloating, are primary causes of dissatisfaction despite general reflux alleviation among these patients. New symptoms occur sooner after fundoplication than recurrent symptoms and may become less common with time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is prevalent in the United States, with GERD-related symptoms affecting nearly 20 % of the adult population weekly and 50 % monthly [1, 2]. The most common symptoms of GERD are heartburn and chest discomfort, which if prolonged and severe can lead to a spectrum of serious sequelae including esophagitis, luminal stricture, Barrett’s metaplasia, and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Although proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) can provide adequate heartburn control in many cases, lifelong medical therapy is expensive; compliance can be a problem; and nearly 40 % of patients have persistent symptoms despite heavy use of PPIs [3].

Laparoscopic fundoplication, an efficacious and durable alternative to medical therapy, currently is considered the “gold standard” surgical treatment for GERD. Laparoscopic fundoplication is associated with excellent short- and long-term reflux resolution rates of 80 to 95 %, and patients can expect less pain, a shorter hospital stay and recovery time, and fewer incisional hernias than with the open technique [4–11].

Despite excellent postoperative outcomes, as defined by objective measures such as pH study or manometry, some patients experience new adverse symptoms including dysphagia, nausea, bloating, prolonged postprandial fullness, and inability to belch and vomit. These new postoperative symptoms or side effects generally include dysphagia, reported by up to 20 % of patients, and abdominal distension and flatulence, reported by more than 40 % of patients [7, 12]. An extensive body of literature has identified these new and recurrent symptoms in patients who experienced failed fundoplication or required redo operations, suggesting that postoperative symptoms may contribute to lower quality of life in these cohorts.

Due to lack of consensus in the literature about the definition of a successful or failed fundoplication, previous studies have used a range of treatment end points including relief of GERD symptoms, improvement in quality of life, avoidance of postoperative complications, and patient satisfaction. Increasingly, patient satisfaction is cited as an important metric of effective treatment, with many studies reporting 90 % satisfaction rates or higher after laparoscopic fundoplication as well as improvements in symptoms and quality of life [9, 10, 13–16]. Despite the widespread reporting of this statistic, little is known about the factors driving patient satisfaction or about the degree to which satisfaction reflects symptomatic outcomes, objective disease, and overall patient experience.

To clarify the implications of satisfaction as a primary therapeutic end point, we investigated the experiences of patients dissatisfied after the operation and delineated the causes of dissatisfaction, using both objective and subjective outcome measures. We hypothesized that patient satisfaction would be influenced by a variety of factors such as patient selection, technical outcome of the operation, symptomatic outcomes, the patient–provider relationship, and patient preferences.

Materials and methods

With institutional review board approval, data for all patients undergoing laparoscopic fundoplication for GERD from 1992 to 2010 were reviewed. Preoperative evaluation included esophageal motility testing by stationary water perfusion esophageal manometry, a barium-laden food bolus esophagram, or both using methods described previously [17, 18]. The indications for fundoplication were gastroesophageal reflux refractory to medical therapy documented by a Bravo pH composite DeMeester score higher than 14.7 or profound symptoms of esophageal obstruction due to hiatal hernia. Laparoscopic Toupet and Dor fundoplications were undertaken for patients with weak esophageal contractions (<30 mmHg) or disordered peristalsis/dysmotility.

Before fundoplication, patients were given questionnaires on which they indicated the frequency and severity of symptoms such as heartburn, regurgitation, chest pain, dysphagia, choking, nausea, gas/bloating, and inability to belch and vomit. Symptoms were scored by the patients using a Likert scale ranging from 0 (never/not bothersome) to 10 (always/very bothersome) [6].

Our technique has been previously described in detail [18]. Briefly, a five-port technique was used with the patients supine. After wide opening of the gastrohepatic omentum, dissection was performed along the right crus. If present, any hiatal hernia was reduced, and a posterior curoplasty was undertaken to close the esophageal hiatal defect. At this point, the posterior fundus was brought behind the esophagus to construct the fundoplication.

Division of short gastric vessels was routinely undertaken in all the patients. A 52- to 60-Fr bougie was placed per os into the stomach. A three-suture technique was used to construct the fundoplication, followed by a lateral gastropexy to tack the posterior fundus to the right crus to remove tension and prevent twisting of the lower esophagus. Trocar sites were closed under laparoscopic visualization using absorbable monofilament suture. Patients routinely began a liquid diet when awake and were discharged home in 24 h with instructions to advance to a soft mechanical diet during the next week. In 2008, our surgical approach was changed from the conventional five-incision laparoscopic fundoplication to a single incision at the umbilicus through which the entire operation was undertaken.

Postoperative questionnaires nearly identical to those given preoperatively were administered in the clinic or by mail 2 and 6 months after fundoplication and annually thereafter. Patients again scored their symptoms and also graded their overall experience as “very satisfying,” “satisfying,” “neither,” “unsatisfying,” or “very unsatisfying.” Patients were asked to rate the outcome of their preoperative symptoms as “excellent” (complete resolution of symptoms), “good” (symptoms less than once per month), “fair” (symptoms less than once per week), or “poor” (exacerbation of symptoms or new troublesome symptoms). Patients also were queried as to whether they would still have the operation knowing what they know now.

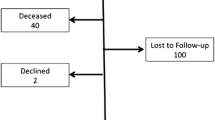

Patients who did not return the questionnaire were contacted, and if possible, a telephone interview was conducted using the questionnaire. Patients who did not have documented acid reflux by pH study, who did not designate a level of satisfaction on questionnaires, or who answered “neither satisfying nor unsatisfying” were excluded from the analysis.

For patients who completed questionnaires, primary complaints after fundoplication were derived from postoperative questionnaires. If incomplete, additional data were obtained from clinic notes and written patient comments. Primary symptom complaints were classified as “new” if the symptoms were absent or not bothersome before the operation, “recurrent” if the patient reported the return of symptoms that had previously been ameliorated, or “persistent” if the patient experienced no improvement or worsening of the symptoms after the operation. Postoperative dysphagia was classified as both a complication and a new symptom when the patient’s inability to swallow was so severe that it required prompt reoperation.

Data were maintained on an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and analyzed using a Wilcoxon matched-pairs test, Fisher’s exact test, or the Mann-Whitney U test when appropriate using GraphPad InStat version 3.06 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Significance was accepted with 95 % probability. Data are presented as median and mean ± standard deviation where appropriate.

Results

From January 1992 to July 2010, 1,063 laparoscopic fundoplications (92 % Nissen, 7 % Toupet, 1 % Dor) were undertaken. Of the 1,063 patients contacted, completed questionnaires were obtained for 849 (80 %) patients, with 63 patients failing to provide information about their level of satisfaction. Of the 786 patients who rated their satisfaction, 381 reported their experience as “very satisfying,” 240 as “satisfying,” 64 as “neither satisfying nor unsatisfying,” 55 as “unsatisfying,” and 46 as “very unsatisfying.” Thus, a total of 101patients (13 %) were dissatisfied with their experience, whereas 621 (79 %) were satisfied.

The operations performed for the 101 ultimately dissatisfied patients included 95 Nissen, 4 Toupet, and 2 Dor fundoplications, with 96 of these operations using conventional laparoscopy and 5 operations using laparoendoscopic single-site surgery (LESS). Patient demographic and clinical data are shown in Table 1.

The satisfied and dissatisfied patients did not differ in terms of gender, age, body mass index (BMI), or preoperative DeMeester scores (Table 1). Both groups had low conversion rates, few intraoperative complications, short hospital stays, and similar follow-up data. However, the dissatisfied patients were more likely to have undergone previous fundoplications (p = 0.005) and to have experienced postoperative complications (p = 0.03) (Table 1). The complications are listed in Table 2. Notably, 20 of the 22 dissatisfied patients undergoing reoperations were originally treated at outside facilities. Hiatal hernias were present in 85 dissatisfied patients (84 %), and 13 of these hernias were “large” or “giant” (Table 3).

New symptoms reported by dissatisfied patients

The dissatisfied patients frequently reported new symptoms including dysphagia, chest pain, nausea, gas/bloating, and inability to belch or vomit (p < 0.05, Fig. 1). New onset of one or more of these symptoms was the primary postoperative complaint reported by 59 % of the dissatisfied patients (Fig. 2). Whereas only 4 % of all the patients stated that they “always” had dysphagia preoperatively (score of 10), 19 % of the dissatisfied patients reported that they “always” had postoperative dysphagia. Additionally, only 5 % of all the patients had trouble belching before the operation, whereas 34 % of the dissatisfied patients experienced severe inability to belch (score, 8–10) after fundoplication.

Of the 70 patients who did not have severe gas and bloating before the operation, 53 % experienced severe gas and bloating (score, 8–10) after the operation. Furthermore, the patients who underwent redo operations had particularly severe dysphagia-related symptoms after the operation compared with the patients who underwent primary fundoplications (Fig. 3). These patients also reported significant increases in postoperative vomiting and regurgitation, which were not common among the patients who underwent primary fundoplications (Fig. 3).

Likewise, the dissatisfied patients who had “giant” or “large” hiatal hernias had more severe postoperative nausea, inability to vomit, and sensations of food stuck in the chest than the patients with smaller hernias (p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U test). However, as indicated by analyses that excluded high-risk patient subsets (patients who underwent reoperation, had “giant” or “large” hiatal hernias, or had paraesophageal hernias or intrathoracic stomachs, respectively), the development of new postoperative symptoms was prevalent and consistently identified across all subsets of the dissatisfied patients.

Recurrent and persistent symptoms reported by dissatisfied patients

Among all the dissatisfied patients, heartburn symptoms decreased significantly in frequency and severity after fundoplication (p < 0.05, Fig. 1). Of the dissatisfied patients, 39 % reported near complete resolution of their heartburn symptoms (score, 0–2). Despite significant improvement, however, heartburn remained notable overall for the dissatisfied patients (median of 4, Fig. 1).

Recurrent symptoms were the primary complaints reported by 23 % of the patients, whereas persistent symptoms were the primary complaints reported by 4 % of the patients (Fig. 2). Postoperative pH testing confirmed reflux recurrence in 14 (61 %) of the 23 patients with primary complaints of reflux, including those five patients with documented anatomic failures (slipped fundic wrap in 3 patients, herniation of the wrap into the chest in 2 patients) (Table 4). The median postoperative DeMeester score for these patients was 45 (62.7 ± 47.9).

Nine patients reporting reflux symptoms had no objective evidence of recurrence. Persistent heartburn that worsened or never improved was uncommon after fundoplication, reported by only two patients. Gas and bloating was a more common persistent complaint of the dissatisfied patients, affecting 21 of the 31 patients who reported severe gas and bloating preoperatively (score, 8–10). Nevertheless, only one of these 21 patients had persistent gas and bloating as the primary postoperative complaint.

Timing of symptom complaints by dissatisfied patients

New symptoms were most commonly reported in the first postoperative year, with dysphagia being the predominant complaint (Fig. 4). Recurrent symptoms typically occurred later during the follow-up period. The majority of these complaints occurred 4 to 7 years after fundoplication (Fig. 4).

The symptom scores similarly indicated the time dependence of symptoms. A higher frequency of dysphagia-related symptoms occurred for the patients who reported dissatisfaction within 1 year after fundoplication, whereas the patients reporting dissatisfaction more than a year after fundoplication had significantly less dysphagia and significantly more “heartburn after sleep” (Fig. 5). However, although dysphagia was reduced among the patients with a longer follow-up period, dysphagia and related symptoms continued to be more frequent and more severe than they were preoperatively for all the patients (Fig. 6).

Other complaints reported by dissatisfied patients

Of the dissatisfied patients, 14 % attributed their dissatisfaction to other issues not directly related to symptomatic outcomes. These included problems with hospital personnel, health care expenses, changes in sleeping habits, nonspecific cough, and residual soreness (Fig. 2). Interestingly, 11 (11 %) of the dissatisfied patients rated their symptomatic outcomes as “good” or “excellent.” These 11 patients had nearly complete relief of heartburn, with a mean frequency score of 2.5 and a severity score of 1.5. Furthermore, 32 % of all the dissatisfied patients answered that they still would undergo the operation knowing what they knew now.

Discussion

Since its introduction in 1991, laparoscopic fundoplication has become the surgical treatment of choice for the definitive therapy of GERD because it confers excellent relief of reflux with a shorter less painful recovery than the open approach [11, 19]. However, elimination of reflux does not guarantee a successful outcome because patients are sometimes plagued by new postoperative symptoms. Using solely objective measures such as ambulatory pH monitoring to determine the success of the operation can therefore be inadequate and often inconsistent with patient-reported symptoms and satisfaction [20].

Although high satisfaction rates have been well documented, the clinical significance of patient satisfaction as a measure of overall treatment efficacy and as an indicator of objective symptomatic outcomes remains ill defined. The current study is the first to provide a targeted profile of the dissatisfied patient after laparoscopic fundoplication and to investigate the causes of dissatisfaction from an objective and individualized patient perspective. We show that patients dissatisfied after fundoplication generally experience a tradeoff between reflux symptom relief and the onset of new symptoms after the operation.

Certain demographic features have been considered predictors of poor outcomes, including signs of advanced disease such as low or absent lower esophageal sphincter pressure, very high DeMeester scores, and the presence of Barrett’s metaplasia, stricture, and esophagitis [21]. Our analysis, however, showed no difference between the DeMeester scores of satisfied and dissatisfied patients, consistent with earlier findings that our patients with very high DeMeester scores generally have good/satisfying outcomes [22].

Other reported risk factors for adverse outcomes include poor response to antacids, presence of comorbidities, and atypical primary symptoms such as sore throat, hoarse voice, and cough [23–26]. Although psychiatric comorbidities and atypical primary symptoms have been shown to decrease satisfaction, patients in our experience reported significant improvement in atypical symptoms, had good outcomes despite comorbidities, and were highly satisfied after fundoplication [6, 27].

We identified a history of prior fundoplication as an important patient-related predictor of dissatisfaction. Compared with primary operations, revisional operations are known to result in longer operative times, higher rates of conversion to open surgery, and higher complication rates [28]. Accordingly, rates of symptom relief after reoperation (70–85 %) are reported to be lower than those reported for primary surgery (85–95 %) [29]. Moreover, the effect of each reoperation appears to be cumulative, with good-to-excellent results reported by 85 % after the first reoperation, 66 % after the second reoperation, and less than 50 % after the third reoperation [30]. Patients who underwent reoperative fundoplication also were found to have less improvement in quality of life and lower patient satisfaction than patients who underwent a single fundoplication [31].

The development of complications and new symptoms after fundoplication appeared to have a stronger predictive value of dissatisfaction. Dissatisfied patients had higher frequency and severity of postoperative symptoms than satisfied patients. Although postoperative dysphagia, chest pain, and heartburn were extremely rare and mild in previous reports for the entire population (median scores of ≤1) [6], these symptoms were pronounced and severe among dissatisfied patients. Increases in symptoms such as dysphagia, chest pain during swallowing, gas and bloating, inability to belch and vomit, and nausea after the operation appeared to overshadow the simultaneous improvements in heartburn.

The majority of dissatisfied patients had primary postoperative complaints related to new symptoms. These complaints were most common during the first year after the operation. Patients who complained of recurrence did so at later times during the follow-up period, generally 2 years or longer after fundoplication. Symptom scores obtained at short versus extended follow-up intervals demonstrated that over time, the incidence of dysphagia-related symptoms decreased and heartburn symptoms increased, suggesting recurrence. Interestingly, however, 9 (39 %) of the 23 patients reported symptoms strongly suggesting that recurrence had no objective evidence of reflux by pH study.

Given our identification of prior fundoplication as a primary risk factor for dissatisfaction, we performed additional analyses that excluded patients who underwent reoperation and patients with large hiatal hernias, which others have previously associated with worse outcomes [32, 33]. In accordance with previous reports, these high-risk subsets had more severe postoperative dysphagia, dysphagia-related symptoms, and nausea, providing evidence for these characteristics as predictors of satisfaction. Nevertheless, the current study identified the development of new symptoms as the strongest predictor of dissatisfaction because these symptoms were the primary complaints of all dissatisfied patients and significantly increased in all patient subsets independently of patient-related risk factors such as large hiatal hernias or history of fundoplication.

In addition to new symptoms, recurrent and persistent reflux symptoms are more common among dissatisfied patients than among satisfied patients [34]. About 0 to 13 % of patients experience long-term reflux recurrence [4, 7, 10, 15, 16, 23, 35], and the majority of them do so with an intact fundoplication [21, 33]. Although PPIs may effectively control the symptoms of these patients, those who experience recurrent reflux that greatly hinders their quality of life may benefit from reoperation.

In the current study, six patients with documented recurrent reflux after the operation subsequently underwent reoperation. One of these patients had reflux resolution confirmed by pH study, and two patients reported their new postoperative experience to be “very satisfying” or “satisfying.” Still, a significant number of patients who complained primarily of recurrent symptoms had no objective evidence of acid reflux.

This apparent disconnect between patient-reported symptoms and objective studies has been observed previously [4, 20, 36, 37]. Kamolz et al. [38] showed that the impairment in quality of life among patients with GERD had little correlation with pathologic evidence of esophagitis and rather was strongly related to patient perceptions of symptom severity before and after an operation. Recurrent reflux symptoms that do not appear to result from actual acid reflux are difficult to treat effectively, making it more likely for these patients to be dissatisfied.

Finally, some patients were dissatisfied due to reasons not directly related to the outcome of the fundoplication. These reasons predominantly focused on aspects of health care delivery such as the interactions of health care personnel with the patient or family or the expenses of the operation. Several of these patients strongly emphasized that their reflux had been relieved by surgery, highlighting that they were solely displeased with hospital care or their health care experience.

Other studies also have noted that health care providers, through their level of competence as well as their communication style, approachability, and expressed concern, greatly influence the quality of the patient experience [39]. A patient’s perception of the complexity and convenience of treatment, the monetary and emotional costs of surgery, and the relative effectiveness of previous treatment can dictate patient expectations of the operation and satisfaction with fundoplication [39]. Ultimately, the achievement of a technically sound operation and the prevention of complications and adverse side effects must be parts of a greater holistic strategy to improve the quality of care and the overall experience for patients undergoing laparoscopic fundoplication.

References

Shaheen N, Ransohoff DF (2002) Gastroesophageal reflux, Barrett esophagus, and esophageal cancer: scientific review. JAMA 287:1972–1981

Spechler SJ, Lee E, Ahnen D, Goyal RK, Hirano I, Ramirez F, Raufman JP, Sampliner R, Schnell T, Sontag S, Vlahcevic ZR, Young R, Williford W (2001) Long-term outcome of medical and surgical therapies for gastroesophageal reflux disease: follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 285:2331–2338

Dean BB, Gano AD Jr, Knight K, Ofman JJ, Fass R (2004) Effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in nonerosive reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2:656–664

Anvari M, Allen C (2003) Five-year comprehensive outcomes evaluation in 181 patients after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. J Am Coll Surg 196:51–57 discussion 57–58; author reply 58–59

Broeders JA, Mauritz FA, Ahmed Ali U, Draaisma WA, Ruurda JP, Gooszen HG, Smout AJ, Broeders IA, Hazebroek EJ (2010) Systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic Nissen (posterior total) versus Toupet (posterior partial) fundoplication for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Br J Surg 97:1318–1330

Cowgill SM, Gillman R, Kraemer E, Al-Saadi S, Villadolid D, Rosemurgy A (2007) Ten-year follow up after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am Surg 73:748–752 discussion 752–743

Dallemagne B, Weerts J, Markiewicz S, Dewandre JM, Wahlen C, Monami B, Jehaes C (2006) Clinical results of laparoscopic fundoplication at ten years after surgery. Surg Endosc 20:159–165

Granderath FA, Kamolz T, Schweiger UM, Pasiut M, Haas CF, Wykypiel H, Pointner R (2002) Long-term results of laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Surg Endosc 16:753–757

Lafullarde T, Watson DI, Jamieson GG, Myers JC, Game PA, Devitt PG (2001) Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: five-year results and beyond. Arch Surg 136:180–184

Vidal O, Lacy AM, Pera M, Valentini M, Bollo J, Lacima G, Grande L (2006) Long-term control of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms after laparoscopic Nissen–Rosetti fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg 10:863–869

Salminen PT, Hiekkanen HI, Rantala AP, Ovaska JT (2007) Comparison of long-term outcome of laparoscopic and conventional nissen fundoplication: a prospective randomized study with an 11-year follow-up. Ann Surg 246:201–206

Kamolz T, Granderath FA, Bammer T, Pasiut M, Pointner R (2002) Dysphagia and quality of life after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication in patients with and without prosthetic reinforcement of the hiatal crura. Surg Endosc 16:572–577

Bammer T, Hinder RA, Klaus A, Klingler PJ (2001) Five- to eight-year outcome of the first laparoscopic Nissen fundoplications. J Gastrointest Surg 5:42–48

Granderath FA, Kamolz T, Schweiger UM, Pointner R (2002) Quality of life, surgical outcome, and patient satisfaction three years after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. World J Surg 26:1234–1238

Hunter JG, Trus TL, Branum GD, Waring JP, Wood WC (1996) A physiologic approach to laparoscopic fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Surg 223:673–685 discussion 685–677

Ruiz-Tovar J, Diez-Tabernilla M, Chames A, Morales V, Sanjuanbenito A, Martinez-Molina E (2010) Clinical outcome at ten years after laparoscopic fundoplication: Nissen versus Toupet. Am Surg 76:1408–1411

Cowgill SM, Bloomston M, Al-Saadi S, Villadolid D, Rosemurgy AS II (2007) Normal lower esophageal sphincter pressure and length does not impact outcome after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg 11:701–707

D’Alessio MJ, Rakita S, Bloomston M, Chambers CM, Zervos EE, Goldin SB, Poklepovic J, Boyce HW, Rosemurgy AS (2005) Esophagography predicts favorable outcomes after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication for patients with esophageal dysmotility. J Am Coll Surg 201:335–342

Dallemagne B, Weerts JM, Jehaes C, Markiewicz S, Lombard R (1991) Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: preliminary report. Surg Laparosc Endosc 1:138–143

Shi G, Tatum RP, Joehl RJ, Kahrilas PJ (1999) Esophageal sensitivity and symptom perception in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 1:214–219

Horvath KD, Jobe BA, Herron DM, Swanstrom LL (1999) Laparoscopic Toupet fundoplication is an inadequate procedure for patients with severe reflux disease. J Gastrointest Surg 3:583–591

Ross SB, Villadolid D, Paul H, Al-Saadi S, Gonzalez J, Cowgill SM, Rosemurgy A (2008) Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication ameliorates symptoms of reflux, especially for patients with very abnormal DeMeester scores. Am Surg 74:635–642 discussion 643

Morgenthal CB, Lin E, Shane MD, Hunter JG, Smith CD (2007) Who will fail laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication? Preoperative prediction of long-term outcomes. Surg Endosc 21:1978–1984

Ratnasingam D, Irvine T, Thompson SK, Watson DI (2011) Laparoscopic antireflux surgery in patients with throat symptoms: a word of caution. World J Surg 35:342–348

Kamolz T, Bammer T, Granderath FA, Pointner R (2002) Comorbidity of aerophagia in GERD patients: outcome of laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Scand J Gastroenterol 37:138–143

Kamolz T, Granderath FA, Pointner R (2003) Does major depression in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease affect the outcome of laparoscopic antireflux surgery? Surg Endosc 17:55–60

Golkar F, Morton C, Ross S, Vice M, Arnaoutakis D, Dahal S, Hernandez J, Rosemurgy A (2010) Medical comorbidities should not deter the application of laparoscopic fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg 14:1214–1219

Iqbal A, Awad Z, Simkins J, Shah R, Haider M, Salinas V, Turaga K, Karu A, Mittal SK, Filipi CJ (2006) Repair of 104 failed antireflux operations. Ann Surg 244:42–51

Spechler SJ (2004) The management of patients who have “failed” antireflux surgery. Am J Gastroenterol 99:552–561

Little AG, Ferguson MK, Skinner DB (1986) Reoperation for failed antireflux operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 91:511–517

Khaitan L, Bhatt P, Richards W, Houston H, Sharp K, Holzman M (2003) Comparison of patient satisfaction after redo and primary fundoplications. Surg Endosc 17:1042–1045

Power C, Maguire D, McAnena O (2004) Factors contributing to failure of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication and the predictive value of preoperative assessment. Am J Surg 187:457–463

Soper NJ, Dunnegan D (1999) Anatomic fundoplication failure after laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Ann Surg 229:669–676 discussion 676–667

Velanovich V (2004) Using quality-of-life measurements to predict patient satisfaction outcomes for antireflux surgery. Arch Surg 139:621–625 discussion 626

Watson DI, Jamieson GG (1998) Antireflux surgery in the laparoscopic era. Br J Surg 85:1173–1184

Draaisma WA, Buskens E, Bais JE, Simmermacher RK, Rijnhart-de Jong HG, Broeders IA, Gooszen HG (2006) Randomized clinical trial and follow-up study of cost-effectiveness of laparoscopic versus conventional Nissen fundoplication. Br J Surg 93:690–697

Lord RV, Kaminski A, Oberg S, Bowrey DJ, Hagen JA, DeMeester SR, Sillin LF, Peters JH, Crookes PF, DeMeester TR (2002) Absence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in a majority of patients taking acid suppression medications after Nissen fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg 6:3–9 discussion 10

Kamolz T, Granderath F, Pointner R (2003) Laparoscopic antireflux surgery: disease-related quality-of-life assessment before and after surgery in GERD patients with and without Barrett’s esophagus. Surg Endosc 17:880–885

Revicki DA (2004) Patient assessment of treatment satisfaction: methods and practical issues. Gut 53(Suppl 4):iv40–iv44

Disclosures

Leigh A. Humphries, Jonathan M. Hernandez, Whalen Clark, Kenneth Luberice, Sharona B. Ross, and Alexander S. Rosemurgy have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Humphries, L.A., Hernandez, J.M., Clark, W. et al. Causes of dissatisfaction after laparoscopic fundoplication: the impact of new symptoms, recurrent symptoms, and the patient experience. Surg Endosc 27, 1537–1545 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-012-2611-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-012-2611-y