Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic surgery is becoming a more widely used approach for benign and malignant lesions in the neck, body, and tail of the pancreas. Recent literature reports appear to demonstrate that laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy (LDP) has clear benefits compared with open distal pancreatectomy (ODP). However, the procedure is relatively new and in some patients may remain a technically demanding operation.

Methods

Twenty-nine LDPs were performed by a single surgeon during the course of 12 months by using a multistep clockwise technique described in detail below. The technique appears to simplify and standardize the approach for both the simpler and the more difficult procedure. Retrospective analysis was performed regarding perioperative outcomes.

Results

Twenty-three procedures were performed for a neoplastic process with five patients having pancreatic adenocarcinoma. There was no conversion to ODP, but one patient required a hand-assist method. Splenectomy was performed in 26 patients. Median operative time, estimated blood loss, and length of stay was 182 min, 50 ml, and 4 days respectively. Overall morbidity and pancreatic fistula rate was 17.2% and 10.3%, respectively. Median number of lymph nodes was 14, concomitant left adrenalectomy was performed in 3 patients, and margins were negative in 28 patients.

Conclusions

LDP has been shown to be an acceptable approach to both benign and malignant disease of the distal pancreas. The technique used in this manuscript appears to facilitate a reliable and safe five-step method to perform this procedure and ensures that appropriate oncologic principles are followed through each step. Even though this is a small feasibility series focused on surgical technique, our results appear to demonstrate an acceptable pancreatic leak rate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

During the past decade, minimal access surgery techniques have rapidly evolved to include a variety of complex surgical procedures. Its role in pancreatic resections, however, has been widely debated and remains an area of controversy. Nevertheless, outcomes of laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy (LDP) have been well described. Even though there is a lack of larger prospective series, multiple reports have demonstrated the feasibility and safety of this procedure in single center [1–7] and multicenter patient series [8–10]. In experienced hands, the minimal access approach has significant advantages compared with open surgery and appears especially well suited for this procedure because of the visual magnification, delicate tissue manipulation, decreased blood loss, enhanced access to the difficult areas, and the absence of need for reconstruction. Nevertheless, experience in open pancreatic surgery and a responsible approach in patient selection is pivotal to ensure that the results of the laparoscopic technique match or improve the results obtained with the open technique in regards to morbidity, mortality, and oncologic outcomes.

It is expected that as experienced pancreatic surgeons become more familiar with minimal access surgery, LDP will rapidly become a widely accepted and preferred technique over open distal pancreatectomy (ODP) for pancreatic pathology of the body and tail of the pancreas. The goal of this report is to describe the technique for distal and subtotal pancreatectomy in a stepwise manner as practiced by the authors with the intention to share details that may aid a pancreatic surgeon in performing the procedure.

This report gives operative details with descriptive figures and pictures, as well as describes our perioperative results of LDP during a 12-month time period using the technique described below.

Materials and methods

Data were collected on all patients undergoing distal or subtotal pancreatectomy during a period of 12 months, from May 2009 to May 2010, performed by the primary surgeon (HJA). Those patients identified were studied in detail and all clinical and pathologic details were entered into a standard database for review. Pancreatic fistula was graded per International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula [11] recommendations. Postoperative 30-day or inpatient morbidity was graded according to the modified Clavien scale [12]. This study was approved by our institutional internal review board. All procedures for patients undergoing LDP were performed as described below in surgical technique.

Surgical technique

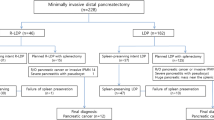

A caudad to cephalad clockwise technique for distal and subtotal pancreatectomy is described (Fig. 1). Subtotal pancreatectomy is referred to a distal pancreatic resection that includes the neck body and tail of the pancreas.

Patient position The patient is placed in a modified right lateral decubitus position that would allow for rotation to the left or right during the procedure. In our experience, this facilitates the exposure of the operative area by allowing gravity do a significant portion of the retraction of the neighboring organs. Care is taken to secure the patient in the position as well as to avoid any points of significant pressure, hyperextension, or hyperflexion. The surgeon stands to the right of the operating table. Four ports are placed as shown (Fig. 2). Two are 12-mm size and two are 5-mm trocars. Energy sources commonly used were ultrasonic shears, monopolar, and bipolar electrocautery.

Step 1: Mobilization of the splenic flexure of the colon and exposure of the pancreas

The operation is started by mobilizing the splenic flexure of the colon. Omental attachments to the lower pole of the spleen are ligated and divided. The colon is reflected medially, and the area of the kidney and Gerota’s fascia are exposed. Lateral attachments to the proximal descending colon are divided. A plane is developed between the Gerota’s fascia and the left colon. This plane is usually avascular and careful blunt dissection allows for good separation between the kidney and the mesocolon. Dissection is then continued cephalad toward the distal portion of the tail of the pancreas. The pancreas is palpated with the instrument and identified. A window is created into the lesser sac, usually immediately anterior to the most distal part of the pancreas. Care is taken to avoid injury to the tail of the pancreas. The stomach is exposed and the short gastric vessels are divided. If readily accessible, the dissection is extended to the most cephalad short gastric vessels, which are divided to separate the upper portion of the spleen from the fundus of the stomach. The gastrocolic omentum is divided from left to right. A plane is developed between the posterior wall of the stomach and body and tail of the pancreas. Attachments between the stomach and the pancreas vary from patient to patient, and it is important to divide these attachments to be able to have complete access to the anterior aspect of the pancreas. A clear exposure of the pancreatic body and tail is obtained by having gravity retraction of the colon, which has been widely mobilized.

Step 2: Dissection along the inferior edge of the pancreas and choosing the site for pancreatic division

The inferior edge of the pancreas is identified and the dissection is started far or closer to the pancreas depending on whether the underlying process is benign or malignant. A window is created in the fibroadipose tissue below the pancreatic edge, and the posterior plane between the retroperitoneum and the pancreas is developed. When in the correct tissue plane, the dissection is generally avascular. The pancreas is gently retracted anteriorly, facilitating exposure of the plane. The dissection is carried under direct visualization. Once the plane is well defined, it is continued from lateral to medial. More superior and anteriorly, the gastrocolic omentum is further divided as needed. The dissection is carried medially past the target lesion. The inferior mesenteric vein is clearly exposed, and it will be the first vascular structure when going from left to right along the inferior edge of the pancreas. An intraoperative ultrasound (US) is performed to identify/confirm clearly the location of the lesion. The site for division of the pancreas is decided based on the intraoperative US. The relationship between the mass and the underlying vasculature also is delineated by US. Once the site for division is decided, the pancreas is retracted superiorly and anteriorly. The dissection is now continued from caudad to cephalad. The more superior attachments between the retroperitoneum and the pancreas are divided. The splenic vein is exposed.

Step 3: Pancreatic parenchymal division and ligation of the splenic vein and artery

Attention is now paid to the completion of the development of the plane behind the pancreas with placement of a Penrose drain around the pancreas in a “lasso technique” fashion described by Velanovich [13]. A finger type dissector is very useful for this part of the dissection/procedure (Fig. 3). The splenic artery is clearly visualized. A window is created immediately superior to the edge of the pancreas. The splenic artery will be dissected along with the pancreas or individually depending if the plane of parenchymal transection is close or far distal to the celiac trunk. The splenic vein is again exposed and the dissection plane is posterior to it, keeping the vein attached to the pancreas for distal resections. For subtotal resections where the neck, body, and tail are included in the resection, the plane developed behind the pancreatic parenchyma is at the level of the neck of the pancreas. In this case, the vein is not incorporated in the dissection and is dissected and ligated separately after division of the pancreatic neck. With the window completed, the pancreas is retracted superiorly and the window is enlarged and the Penrose drain may be passed to facilitate retraction of the pancreas. For distal resections, there is usually no need to dissect the splenic artery separately and its ligation and division are performed en block with the pancreas. For subtotal and more proximal distal resections, the artery is dissected and ligated separately. The deciding factor for individual splenic artery ligation is the proximity of the site of pancreatic dissection to the celiac trunk. When close to the celiac trunk, individual dissection and identification of the artery is crucial to avoid injuring the celiac trunk or any of its branches, mainly the hepatic artery.

The division and ligation of the parenchyma can be safely done in the large majority of cases with a stapler. A stapler is used only when the thickness of the pancreatic parenchyma allows it. The stapler is gently passed around the pancreatic parenchyma and positioned carefully. It is not necessary to completely transect the pancreas with one application of the stapler. In many instances, a partial transection of the pancreas will facilitate better exposure of the superior edge of the pancreas and the splenic artery for later ligation and division. Further development of the plane is done and a second application of the stapler is used to ligate and divided the splenic artery. All of this is done under direct visualization. It is important to gradually close the stapler in a stepwise manner over the course of 2–3 min. Compressing the pancreatic parenchyma little by little with the stapler will allow for thinning of the pancreatic parenchyma by reducing the fluid within the parenchyma at the transection line. One can feel the resistance of the parenchyma with each step of compression. Because of this, a clamping type stapler is preferred. The use of absorbable stapler reinforcement sheet also is favored. The staple cartridge length will depend on the thickness of the parenchyma but usually a 3.5-mm or 4.8-mm size staple load is used, even with en bloc ligation of the artery or vein with the parenchyma. As mentioned earlier, when the division of the pancreatic parenchyma is close to the celiac trunk, the splenic artery should be clearly identified and the anatomy of the celiac trunk clearly defined. To ligate the splenic artery separately, a window is created around the splenic artery, freeing the artery circumferentially. Clips are applied proximally to the splenic artery taking care not to compromise vessels originating from the celiac trunk. The artery is then divided. An extended lymphadenectomy of the celiac trunk can be performed if necessary. The attachments of the superior edge of the pancreas to the celiac trunk are divided and the anatomy is exposed. In very few cases, the pancreatic parenchyma is too thick at the division site and the use of a stapler is not advised. In that situation, our preference is to divide the pancreas with ultrasonic shears in a fish mouth fashion. The proximal divided edge is then sutured with a running nonabsorbable monofilament suture. Particular care is taken to identify and individually ligate the main pancreatic duct if possible. This is done in similar manner as in an open procedure.

Step 4: Dissection along the superior edge of the pancreas

Once the pancreas and the vasculature have been completely ligated and divided, the dissection is now continued along the superior edge of the pancreas from medial to lateral. Up to this stage, the superior attachments of the body and tail of the pancreas lateral to the division site had been kept intact. The pancreas is initially retracted inferiorly, clearly exposing its attachments of the superior border to the retroperitoneum. Further attachments between the stomach and the pancreas are divided. This is best accomplished by using a large De-Bakey-type grasper straddling and retracting the specimen from medial to lateral. If any residual short gastric vessels are present, there are ligated and divided at this stage. As the distal pancreas is reached, the pancreas is retracted inferiorly and to the left to expose the superior attachments as well as anteriorly and to the left when the posterior attachments are divided. If a modified posterior radical antegrade modular pancreatospenectomy (RAMPS)-type procedure is being performed [14], the left adrenal gland and Gerota’s fascia are readily exposed and can be excised with the specimen en bloc. Care is taken to identify the adrenal vein and avoid injuring the left renal vein.

Step 5: Mobilization of the spleen and specimen removal

The last step is mobilization of the spleen and is done by exposing and dividing its posterior, lateral, and superior attachments. Lower posterior attachments of the spleen are exposed first medially. Then the spleen is retracted to the right and the dissection is carried from lateral to medial by dividing the attachments of the spleen to the lateral abdominal wall and to the diaphragm. This dissection is carried from caudad to cephalad.

Specimen removal A thin band of tissue can be left attached to the superior pole of the spleen to fix the specimen and facilitate placement into the endoscopic retrieval bag. The mouth of the bag is then exteriorized through the umbilical blunt port. The incision site is enlarged/extended and the specimen is gradually removed. In the event of a large spleen, the spleen can be partially cut in small pieces, morselized within the bag. Care is taken to preserve the pancreatic parenchyma intact for pathologic evaluation of margins around the tumor. Frozen section of the pancreatic medial margin is obtained. A drain may be placed in the operative bed according to the surgeon’s preference.

Results

From May 2009 to May 2010, 29 patients underwent LDP using the technique as described above. There were no conversions to ODP in any patient, but there was one patient who required conversion to hand-assisted laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy (HA-LDP). During this time period, the author also performed one ODP for a patient with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with multiple previous upper abdominal operations. The demographics and outcomes for this cohort are given in Tables 1 and 2.

Pancreatic parenchymal transection was performed with stapling device and staple line reinforcement for all cases. Splenectomy was performed in 26 patients, and a splenic preserving procedure was done in 3 patients. An operatively placed peripancreatic drain was used in 12 (41%) patients. Twenty-two patients underwent histological analysis of peripancreatic lymph node in the operative specimen and the median number of lymph nodes for this group was 14 (range, 3–48). For those with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, the median number of lymph nodes found by pathology was 19 (range, 10–48). In 28 of the 29 patients, all margins of resection were free of disease (R0). The one patient who had a positive margin on final histology had undergone conversion to HA-LDP with resection of a large pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, which had invaded into the retroperitoneum and was found to have a histological positive radial margin (R1). Three patients underwent concomitant left adrenalectomy (modified RAMPS) and two other patients underwent a concomitant liver resection and gastric wedge resection for metastatic neuroendocrine tumor and gastrointestinal stromal tumor respectively. One patient required an intraoperative blood transfusion, and one patient required a postoperative blood transfusion during the hospitalization.

Five patients (17.2%) experienced a postoperative complication: three (10.3%) with pancreatic fistula (Table 2). One patient with pancreatic adenocarcinoma was noticed to have a port site recurrence at 2 months. This mass was noticed by the patient at a port site, which had been used for postoperative closed suction drainage and was successfully locally excised. The patient has not had any other signs of tumor recurrence with 14 months follow-up. Upon review of this operative procedure, no unusual circumstances were noted regarding tumor extraction or use of irrigation compared with the rest of the group. Except for this local reexcision, no other reoperations were required within this series.

Discussion

Multiple previous studies have demonstrated the safety of LDP, as well as it benefits over ODP. More recently, the Central Pancreas Consortium, a multicenter group of academic university medical centers, have published data regarding the results of a direct matched cohort comparison analysis of patients undergoing LDP vs. ODP. During their first analysis, LDP was associated with lower blood loss, shorter length of stay, and lower overall morbidity and concluded that a laparoscopic approach is the preferred method of surgery for pancreatic pathology [9]. However, the question concerning the oncologic consequences of laparoscopic pancreatic surgery when applied to pancreatic adenocarcinoma still remained. A second analysis from the same group compared the results of LDP and ODP when applied to pancreatic ductal carcinoma. Cancer outcomes were compared in short-term (node harvest and margin status) and long-term (survival) in these two groups and were found to be similar for both groups [10].

Although operative technique was not standardized or described in this second report from the Central Pancreas Consortium, the technique described above facilitates full oncologic resection for any malignant process and gives comparable short-term results. The single patient with port site metastases is unexplained and does not appear to be representative of this procedure based on previous literature reports [1–10] and author experience during the past 16 years. Nevertheless, this event needs to be taken into account and surgeons should be aware of the potential for this to occur, although unusual.

Similar to the radical antegrade modular pancreatiosplenectomy (RAMPS) procedure described by Strasberg [14], this technique affords wide exposure of the pancreas and the plane of dissection can be chosen to include or exclude the left adrenal gland, Gerota’s fascia, or the superior leaflet of the transverse colon mesentery. Some reports have indicated that peripancreatic or retropancreatic infiltration is an absolute contraindication to LDP [15]; however, the modified RAMPS procedure was performed successfully for three of our patients with minimal technique variation. A wider dissection will increase inclusion of the surrounding lymphatics and facilitate a proper oncologic clearance. This was seen in our series where the median lymph node harvest for LDP done for pancreatic adenocarcinoma was 19 nodes.

The clockwise, caudad to cephalad approach appears to have other significant technical advantages that facilitate the performance of the procedure. The approach allows for displacement of the colon and omentum medially and inferiorly by gravity. The lesser sac is entered from a lateral approach, after the splenic flexure of the colon is taken down. The gastrocolic omentum is divided and ligated from lateral to medial. This avoids losing time in the dissection of the different layers of fibropadipose adhesions that surround the splenocolic ligament and gives ample access to the pancreatic body and tail early in the procedure. A reproducible staple technique for division of the pancreas is described and it appears to provide with an acceptable leak rate.

In conclusion, the above technique is a simplified step-by-step process of first creating wide exposure of the pancreas, which then facilitates choosing the site of transection, creating a retropancreatic tunnel, pancreatic transection, and pancreas mobilization with removal. This technique can be applied for all lesions of the body and tail of the pancreas and modified according to suspicion of malignancy or peripancreatic invasion as needed. Initial results in different series appear to confirm the expected advantages of the laparoscopic approach.

Abbreviations

- LDP:

-

Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy

- OPD:

-

Open distal pancreatectomy

- IPMN:

-

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm

- RAMPS:

-

Radical antegrade modular pancreatospenectomy

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

References

Melotti G, Butturini G, Piccoli M, Casetti L, Bassi C, Mullineris B, Lazzaretti MG, Pederzoli P (2007) Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: results on a consecutive series of 58 patients. Ann Surg 246(1):77–82

Palanivelu C, Shetty R, Jani K, Sendhilkumar K, Rajan PS, Maheshkumar GS (2007) Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: results of a prospective non-randomized study from a tertiary center. Surg Endosc 21(3):373–377

Kim SC, Park KT, Hwang JW, Shin HC, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH, Han DJ (2008) Comparative analysis of clinical outcomes for laparoscopic distal pancreatic resection and open distal pancreatic resection at a single institution. Surg Endosc 22(10):2261–2268

Fernández-Cruz L, Cosa R, Blanco L, Levi S, López-Boado MA, Navarro S (2007) Curative laparoscopic resection for pancreatic neoplasms: a critical analysis from a single institution. J Gastrointest Surg 11(12):1607–1621; discussion 1621–1622

Taylor C, O’Rourke N, Nathanson L, Martin I, Hopkins G, Layani L, Ghusn M, Fielding G (2008) Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: the Brisbane experience of forty-six cases. HPB (Oxford) 10(1):38–42

Laxa BU, Carbonell AM II, Cobb WS, Rosen MJ, Hardacre JM, Mekeel KL, Harold KL (2008) Laparoscopic and hand-assisted distal pancreatectomy. Am Surg 74(6):481–486; discussion 486–487

Pryor A, Means JR, Pappas TN (2007) Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy with splenic preservation. Surg Endosc 21(12):2326–2330

Mabrut JY, Fernandez-Cruz L, Azagra JS, Bassi C, Delvaux G, Weerts J, Fabre JM, Boulez J, Baulieux J, Peix JL, Gigot JF (2005) Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Section (HBPS) of the Royal Belgian Society of Surgery; Belgian Group for Endoscopic Surgery (BGES); Club Coelio. Laparoscopic pancreatic resection: results of a multicenter European study of 127 patients. Surgery 137(6):597–605

Kooby DA, Gillespie T, Bentrem D, Nakeeb A, Schmidt MC, Merchant NB, Parikh AA, Martin RC II, Scoggins CR, Ahmad S, Kim HJ, Park J, Johnston F, Strouch MJ, Menze A, Rymer J, McClaine R, Strasberg SM, Talamonti MS, Staley CA, McMasters KM, Lowy AM, Byrd-Sellers J, Wood WC, Hawkins WG (2008) Left-sided pancreatectomy: a multicenter comparison of laparoscopic and open approaches. Ann Surg 248(3):438–446

Kooby DA, Hawkins WG, Schmidt CM, Weber SM, Bentrem DJ, Gillespie TW, Sellers JB, Merchant NB, Scoggins CR, Martin RC III, Kim HJ, Ahmad S, Cho CS, Parikh AA, Chu CK, Hamilton NA, Doyle CJ, Pinchot S, Hayman A, McClaine R, Nakeeb A, Staley CA, McMasters KM, Lillemoe KD (2010) A multicenter analysis of distal pancreatectomy for adenocarcinoma: is laparoscopic resection appropriate? J Am Coll Surg 210(5):779–785, 786–787

Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M (2005) International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula Definition. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition [review]. Surgery 138(1):8–13

DeOliveira ML, Winter JM, Schafer M, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Clavien PA (2006) Assessment of complications after pancreatic surgery: a novel grading system applied to 633 patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 244(6):931–937; discussion 937–939

Velanovich V (2006) The lasso technique for laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. Surg Endosc 20(11):1766–1771

Strasberg SM, Linehan DC, Hawkins WG (2007) Radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy procedure for adenocarcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas: ability to obtain negative tangential margins. J Am Coll Surg 204(2):244–249

Kang CM, Kim DH, Lee WJ (2010) Ten years of experience with resection of left-sided pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: evolution and initial experience to a laparoscopic approach. Surg Endosc 24(7):1533–1541

Disclosures

Drs. John A. Stauffer and Horacio J. Asbun have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Asbun, H.J., Stauffer, J.A. Laparoscopic approach to distal and subtotal pancreatectomy: a clockwise technique. Surg Endosc 25, 2643–2649 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-011-1618-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-011-1618-0