Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic repair of a large hiatal hernia is technically challenging. A significant learning curve likely exists that has not been studied to date.

Methods

Since 1992, the authors have prospectively collected data for all patients undergoing laparoscopic repair of a very large hiatal hernia (50% or more of the stomach within the chest). Follow-up evaluation was performed after 3 months, then yearly. Visual analog scores were used to assess heartburn and dysphagia. Patients were grouped according to institutional and individual surgeons’ experience to determine the impact of any learning curve. The outcome for procedures performed by consultant surgeons was compared with that for trainees.

Results

From 1992 to 2008, 415 patients with a 1-year minimum follow-up period were studied. Institutional and individual experience had a significant influence on operation time, conversion to open surgery, and length of hospital stay. However, except for heartburn scores during a 3-month follow-up evaluation of institutional experience (p = 0.03), clinical outcomes were not influenced by either an institutional or individual learning curve. Furthermore, in general terms, whether the procedure was performed by a consultant or a supervised trainee had little effect on outcome.

Conclusions

Institutional and individual learning curves had no significant influence on clinical outcomes, although improved experience was reflected in improved operation time, conversion rate, and hospital stay. These outcomes improved over the first 50 institutional cases, and the outcomes for individual surgeons improved for up to 40 cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) can present with variably sized hiatal hernias, ranging up to a completely intrathoracic stomach. Laparoscopic surgery for very large hernias, defined as more than 50% of the stomach located within the thoracic cavity, is technically more challenging than surgery for reflux alone [1]. Repair entails dissection of the hernia sac from the mediastinum, reduction of the sac and its contents into the abdomen, hiatal repair, and then a fundoplication or gastropexy [2]. Such surgery is associated with procedure-specific risks including perforation of the gastrointestinal tract, pneumothorax, and postoperative dysphagia [3, 4].

Previous studies have shown that most advanced laparoscopic procedures are associated with a distinct learning curve, and the learning curve for each procedure can be defined [5–12]. For laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, the number of cases managed by the individual surgeon and the number of cases managed in an individual institution correlate with operation time, complications, reoperation, and conversion rate, and these outcomes generally stabilize beyond a surgeon’s first 20 cases or an institution’s first 50 cases [5–8, 11, 12]. However, no studies have evaluated the impact of a learning curve on laparoscopic repair of very large hiatal hernias. Hence, in this study, we evaluated our experience with patients who underwent laparoscopic repair of a very large hiatal hernia to determine the influence of any institutional or individual learning curves on clinical outcomes.

Patients and methods

From September 1992 to December 2008, perioperative and follow-up data for all patients who underwent laparoscopic surgical treatment of gastroesophageal reflux or a very large hiatal hernia in our units were collected prospectively and managed using a computerized database (FileMaker Pro, Version 8; FileMaker Inc, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Surgery was undertaken at two university teaching hospitals and associated private hospitals in Adelaide, South Australia, by surgeons or trainees working under direct supervision. A total of 21 fundoplications for gastroesophageal reflux were successfully completed laparoscopically before we began laparoscopic repair of very large hiatal hernias.

The analysis included all the patients who underwent laparoscopic repair of a very large hiatal hernia, defined as at least 50% of the stomach within the chest either at preoperative barium meal radiology assessment or intraoperatively, and were followed clinically for at least 12 months after surgery. These patients had mechanical symptoms attributable to their very large hiatal hernia, and a subset of these patients also had symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux.

The preoperative workup for these patients included an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, and for most of the patients, a barium meal X-ray was performed to clarify anatomy. Esophageal manometry and pH monitoring were undertaken if gastroesophageal reflux also was a significant problem. If reflux was not a significant issue and the planned surgery included an anterior partial fundoplication as a gastropexy, esophageal manometry was sometimes omitted, especially for patients presenting acutely.

Demographic data, operative details, perioperative complications, and the length of hospital stay were documented. All the patients were asked to complete a structured questionnaire 3 months after surgery, again at 1 year, and then yearly thereafter.

The questionnaire included questions that inquired about symptoms of reflux, postsurgical symptoms, potential side effects, and overall satisfaction with the outcome of surgery. The presence or absence of bloating symptoms and the ability to belch normally were assessed using yes/no questions. Patients were asked to score any symptoms of “heartburn” or “dysphagia” for solid food using a visual analog scale (VAS) ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 10 (severe symptoms). Overall satisfaction with the outcome of surgery was evaluated using a visual analog scale ranging from 0 (dissatisfied) to 10 (satisfied). Patients also were asked whether they thought their original decision to undergo surgery was correct or not.

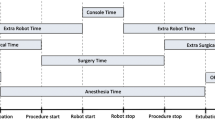

The technique for laparoscopic repair of very large hiatal hernia has been described previously [2, 13]. In brief, the hernia sac was dissected from the mediastinum, and the esophagus was dissected next. Posterior hiatal sutures, supplemented as necessary by additional anterior sutures, then were used to repair the widened hiatus. A fundoplication was constructed last.

From 1992 to early 1996, the principle of dissecting the sac from the mediastinum was not well understood, and attempts were made to dissect the esophagus first rather than the sac [6]. Furthermore, in the earlier years of this series, a Nissen fundoplication with a 360° wrap was performed routinely. At that time, this was our standard antireflux procedure.

Over the past decade, this practice has changed. A greater proportion of anterior partial fundoplications (90° or 180°) are now performed. We have demonstrated elsewhere that an anterior partial fundoplication is an effective procedure for the treatment of reflux and that it minimizes the risk of postfundoplication side effects [14].

The influence of institutional and individual learning experience on clinical outcomes (heartburn, dysphagia, other side effects, and overall satisfaction), intraoperative variables (operation time, conversion rate, perioperative surgical complications), and postoperative complications was determined. Follow-up information at 3 and 12 months was analyzed.

To evaluate an institutional learning curve, patients were chronologically grouped according to case numbers as follows: 1–10, 11–20, 21–50, and groups of 50 thereafter. To evaluate the learning curve for individual surgeons, groups of 10 cases for each surgeon were chronologically defined and grouped into the first 10 cases, the second 10 cases, and so on.

Additionally, outcomes for surgery performed by consultant surgeons were compared with outcomes for surgery performed by trainees. All the trainees were upper gastrointestinal surgery fellows who had completed training in general surgery. To minimize the potential bias of including the learning curve for consultants in the latter analysis, the first 20 cases managed by each consultant surgeon were excluded.

Data are presented as medians with 95% confidence intervals or means with standard deviations. Comparison of data between groups was undertaken using χ2 tests for categorical data and the Student’s t-test, the Mann–Whitney U test, or the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous data, as applicable. Statistical significance was set at a p value less than 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with MedCalc, version 9 for Windows.

Results

This series consisted of 454 patients who had undergone primary laparoscopic repair of a very large hiatal hernia. Of these patients, 415 who had undergone minimum clinical follow-up evaluation for at least 1 year formed the study group. The study excluded 39 patients because they had undergone surgery less than 12 months before the study began. Perioperative data were available for all the patients. Functional follow-up information at 3-month and 1-year time points were not available for 56 (13.5%) and 90 (21.7%) patients, respectively. The median age of the patients was 66 years (95% CI, 65–68), and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 29.6 ± 5.2 kg/m2.

The operations were performed by 9 consultant surgeons and 39 trainees. The median operation time was 95 min (95% CI, 90–105; range, 30–270 min), and the median hospital stay was 3 days (95% CI, 3–3; range, 1–55 days). The mean follow-up period was 48 months (95%, CI 36–48; range, 1–16 years).

The perioperative “medical” complications included 16 pulmonary complications (basal atelectasis, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism), 4 cardiac complications (acute myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmias), urinary retention, and deep venous thrombosis. The surgical complications included 5 esophageal injuries (2 from passage of a bougie and 3 during direct dissection), 2 proximal gastric injuries, 2 vascular injuries (inferior vena cava, accessory left hepatic artery), 1 liver laceration, and 10 postoperative pneumothoraces.

Reoperations were performed for 24 patients (5.8%) within 1 year of their initial surgery. Of these 24 reoperations, 9 were performed for acute recurrence of hiatal hernia, 6 for severe dysphagia, 5 for esophageal or gastric leakage, 2 for postoperative bleeding, 1 for a bilobed stomach [15] causing postprandial pain, and 1 for recurrent reflux due to a slipped Nissen fundoplication. Two in-hospital deaths occurred: one related to esophageal perforation and one due to a postoperative myocardial infarction.

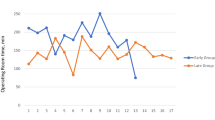

The analysis of the overall institutional experience is shown in Table 1. The operation time declined after the initial 20 cases in the overall institutional experience. However, it increased slightly after 150 cases before slowly tapering downward thereafter. The rate of conversion to an open procedure was higher for the first 50 cases and decreased thereafter (Fig. 1). The length of hospital stay decreased with overall experience. The reoperation rate within 1 year and the rate of surgical complications decreased after the first 20 cases. The incidence of complications decreased at the beginning of the period and increased toward the end.

In terms of clinical outcomes, the heartburn score at 3 months was the only measure that differed significantly over the course of this study, increasing with experience up to 350 cases. All other clinical outcomes were not significantly influenced by institutional experience.

Increasing the experience of individual surgeons did not affect the clinical outcomes (Table 2). The duration of surgery and the length of hospital stay were the only two outcomes that improved over time. The rate of conversion to open surgery decreased to 0% after the first 40 cases for each individual surgeon (Fig. 2).

After exclusion of the initial 20 cases performed by each consultant, 175 patients who had surgery performed by consultants were compared with 130 patients whose surgery was performed by trainees (Table 3). The basic demographic details as well as the preoperative heartburn and dysphagia scores were similar whether the surgery was performed by consultants or trainees. The only significant difference in terms of functional outcomes was a lower dysphagia score at the 1-year follow-up assessment for the trainee group than for the consultant group (mean score, 1.2 vs. 1.8). There were no significant differences in any of the other outcomes, except that the consultants performed the operation 10 min faster than the trainees. Concerning fundoplication types, trainees and consultants performed a similar proportion of total versus partial fundoplications (trainees 35.4% total fundoplication vs consultants 28.6%; p = 0.253).

Discussion

This study showed improvements in perioperative variables with increasing institutional and individual experience, suggesting an institutional “learning curve” of 50 cases and an individual “learning curve” of up to 40 cases, although these differences in perioperative outcomes were not associated with any significant differences in clinical outcomes. Many of the perioperative parameters improved significantly with increasing institutional experience, suggesting improved efficiency.

The length of surgery decreased steadily for the first 150 cases, followed by a distinct increase and then by another decrease. The largest component of this occurred in the first 50 cases, and this probably reflects a learning curve, although we are unable to give a satisfactory explanation for the increase and then the subsequent decrease beyond 150 cases.

Operative technique such as fundoplication type or division of short gastric vessels did not change significantly beyond the first 150 cases, although it is possible that with increasing experience, more complex cases were referred for surgery. Another possible reason might be the increase of cases managed in private hospitals. These operations were performed mostly by a consultant assisted by an inexperienced assistant, in contrast to the public sector, in which the surgical team normally consists of a consultant and a senior trainee.

We identified a significant reduction in the conversion rate from laparoscopic to open surgery from 1996 onward. This coincided with the formalizing of our operating technique so that the hernia sac is first dissected from the mediastinum, as opposed to initial dissection of the esophagus. We described the impact of this on the conversion rate in an earlier paper [2]. As the rate of open procedures decreased, the length of hospital stay also fell significantly.

The only clinical outcome that changed with time as our institutional experience progressed was “heartburn.” The mean scores for “heartburn” remained low at all times, although the scores were slightly higher later in our institutional experience, reflecting a greater proportion of patients undergoing an anterior 90° partial rather than a Nissen fundoplication during the latter years of this study. Most randomized trials enrolling patients primarily with gastroesophageal reflux suggest slightly less “heartburn” after Nissen than after anterior partial fundoplication, although the overall outcome after anterior partial fundoplication still is excellent in most reports [16–18].

Analysis of the clinical outcomes for the individual surgeons did not show any significant changes as experience progressed. This might reflect the fact that most of the surgeons in this study were already experienced in laparoscopic antireflux surgery before starting repair of large hiatal hernias. Satisfaction scores were consistently high throughout the study period for both overall institutional and individual surgeon experiences, supporting the contention that a good clinical or functional outcome can be achieved for laparoscopic repair of very large hiatal hernias even early in a surgeon’s experience.

Surgical morbidity also decreased over time, although the reduction did not reach statistical significance. This again suggests an effect of experience. The two instances of esophageal perforation during passage of a bougie in the formation of a Nissen wrap reflect known risks [19, 20]. However, the esophageal perforations during anterior partial fundoplications were dissection injuries because bougies were not used during these procedures. The rate of other medical complications declined initially but actually increased with further institutional experience. This may have been due to older patients undergoing laparoscopic repair.

Previous studies of learning curves for various other laparoscopic procedures have estimated that a minimum of 20 individual cases and 50 institutional cases are required for achievement of adequate proficiency in performing the procedures [5, 10, 21, 22]. This finding was reflected in our analysis, although the individual surgeon’s experience continued to improve in terms of operation time, length of hospital stay, and conversion rate for a period up to 40 cases, suggesting that for laparoscopic repair of very large hiatal hernias, the individual learning curve is longer than for laparoscopic fundoplication used in patients without a very large hiatal hernia [5]. The majority of the improvement in our institutional experience occurred during the first 50 cases, and this was consistent with other procedures.

Comparison of consultants and trainees demonstrated little difference in clinical outcomes. No differences in conversion rate, morbidity, or reoperation rate were observed. However, the median operation time was 10 min shorter when a consultant performed the procedure. Analysis of the demographic variables and the preoperative heartburn and dysphagia scores suggested similar case selection for trainees and consultants. In the context of delivering a clinical service and training surgeons in a teaching hospital environment, the 10-min time difference probably is not significant. The small difference could reflect the fact that the trainees were “fellows” and thus qualified general surgeons with earlier experience in other laparoscopic procedures who started performing this operation only after they had achieved competence in other laparoscopic procedures, including fundoplication. The trainees also were directly assisted by a consultant. Overall, however, from the patients’ perspective, it does not seem to matter whether the consultant performs the operation, assists, or supervises a senior trainee.

Regarding longer-term outcomes, senior surgeons may like to believe that the outcomes for consultant surgeons would exceed those for trainees. We were not able to test this with our data set. However, the similar earlier outcomes demonstrated in our study are likely to translate to equivalent longer-term outcomes, and in the absence of evidence to the contrary, it seems reasonable to assume that the outcomes after surgery undertaken by trainees are just as good as those of consultant surgeons.

Our study had some potential weaknesses. We progressively changed the type of fundoplication performed over the course of this study, from a routine Nissen fundoplication initially to a predominantly anterior fundoplication approach more recently. However, the major components of the operation (dissection of the sac and repair of the hiatal defect) were standardized throughout the series, and varying the fundoplication likely did not have a significant impact on most of the parameters analyzed.

However, in 1996, we did change the first operative step from initial dissection of the esophagus to dissection of the hernia sac. This had an impact on the conversion rate and certainly was a significant contributor to this aspect of the early institutional learning curve.

A further criticism could target the choice of outcomes evaluated. We did not routinely evaluate objective outcomes for barium meal, pH studies, or gastroscopy. This would not have been practical at all of the clinical follow-up time points. Previously, however, we did evaluate outcomes for barium meal radiology and reported a 25% incidence of small asymptomatic hiatal hernia during longer follow-up periods [3]. However, these radiologic outcomes were not associated with adverse clinical outcomes, and for this reason we believe that the clinical parameters evaluated, especially patient satisfaction, are informative of both the clinical outcome and the learning curve identified in our study.

In conclusion, the clinical outcomes after laparoscopic repair of very large hiatal hernia are not adversely influenced by an institutional or individual learning curve. However, perioperative and short-term postoperative variables improved over the first 100 cases in our institutional experience, particularly during the first 50 cases, and the outcomes for individual surgeons improved for up to 40 cases. Whether the operation is performed by a consultant or a supervised trainee, however, does not influence the clinical outcome after this operation.

References

Draaisma WA, Gooszen HG, Tournoij E, Broeders IA (2005) Controversies in paraesophageal hernia repair: a review of literature. Surg Endosc 19:1300–1308

Watson DI, Davies N, Devitt PG, Jamieson GG (1999) Importance of dissection of the hernial sac in laparoscopic surgery for large hiatal hernias. Arch Surg 134:1069–1073

Aly A, Munt J, Jamieson GG, Ludemann R, Devitt PG, Watson DI (2005) Laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernias. Br J Surg 92:648–653

Mattar SG, Bowers SP, Galloway KD, Hunter JG, Smith CD (2002) Long-term outcome of laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. Surg Endosc 16:745–749

Watson DI, Baigrie RJ, Jamieson GG (1996) A learning curve for laparoscopic fundoplication: definable, avoidable, or a waste of time? Ann Surg 224:198–203

Hwang H, Turner L, Blair NP (2005) Examining the learning curve of laparoscopic fundoplication at an urban community hospital. Am J Surg 189:522–526

Voitk A, Joffe J, Alvarez C, Rosenthal G (1999) Factors contributing to laparoscopic failure during the learning curve for laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication in a community hospital. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 9:243–248

Carlson MA, Frantzides CT (2001) Complications and results of primary minimally invasive antireflux procedures: a review of 10,735 reported cases. J Am Coll Surg 193:521–523

Tekkis PP, Senagore AJ, Delaney CP, Fazio VW (2005) Evaluation of the learning curve in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: comparison of right-sided and left-sided resections. Ann Surg 242:83–91

Schlachta CM, Mamazza J, Seshadri PA, Cadeddu M, Gregoire R, Poulin EC (2001) Defining a learning curve for laparoscopic colorectal resections. Dis Colon Rectum 44:217–222

Ahlberg G, Kruuna O, Leijonmarck C, Ovaska J, Rosseland A, Sandbu R, Strömberg C, Arvidsson D (2005) Is the learning curve for laparoscopic fundoplication determined by the teacher or the pupil? Am J Surg 189:184–189

Zacharoulis D, O’Boyle CJ, Sedman PC, Brough WA, Royston CMS (2006) Laparoscopic fundoplication: a 10-year learning curve. Surg Endosc 20:1662–1670

Wijnhoven BPL, Watson DI (2008) Laparoscopic repair of a giant hiatus hernia: how I do it. J Gastrointest Surg 12:1459–1464

Shukri MJ, Watson DI, Lally CJ, Devitt PG, Jamieson GG (2008) Laparoscopic anterior 90° fundoplication for reflux or large hiatus hernia. ANZ J Surg 78:123–127

Jamieson GG, Watson DI, Britten-Jones R, Mitchell PC, Anvari M (1994) Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Ann Surg 220:137–145

Ludemann R, Watson DI, Jamieson GG, Game PA, Devitt PG (2005) Five-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic total versus anterior 180° fundoplication. Br J Surg 92:240–243

Baigrie RJ, Cullis SNR, Ndhluni AJ, Cariem A (2005) Randomized double-blind trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication versus anterior partial fundoplication. Br J Surg 92:819–823

Watson DI, Jamieson GG, Lally C, Archer S, Bessell JR, Booth M, Cade R, Cullingford G, Devitt PG, Fletcher DR, Hurley J, Kiroff G, Martin CJ, Martin IJ, Nathanson LK, Windsor JA (2004) Multicenter, prospective, double-blind, randomized trial of laparoscopic Nissen versus anterior 90 degrees fundoplication. Arch Surg 139:1160–1167

Schauer PR, Meyers WC, Eubanks S, Norem RF, Franklin M, Pappas TN (1996) Mechanisms of gastric and esophageal perforations during laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Ann Surg 223:43–52

Lowham AS, Filipi CJ, Hinder RA, Swanstrom LL, Stalter K, dePaula A, Hunter JG, Buglewicz TG, Haake K (1996) Mechanisms and avoidance of esophageal perforation by anesthesia personnel during laparoscopic foregut surgery. Surg Endosc 10:979–982

Kim J, Edwards E, Bowne W, Castro A, Moon V, Gadangi P, Ferzli G (2007) Medial-to-lateral laparoscopic colon resection: a view beyond the learning curve. Surg Endosc 21:1503–1507

Jin SH, Kim DY, Kim H, Jeong IH, Kim MW, Cho YK, Han SU (2007) Multidimensional learning curve in laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc 21:28–33

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participating surgeons for contributing to the database and Prof. A. Esterman, PhD, for support with the statistical analysis.

Disclosures

Eu Ling Neo, Urs Zingg, Peter G. Devitt, Glyn G. Jamieson, and David I. Watson have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

E. L. Neo and U. Zingg contributed equally.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Neo, E.L., Zingg, U., Devitt, P.G. et al. Learning curve for laparoscopic repair of very large hiatal hernia. Surg Endosc 25, 1775–1782 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-1461-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-1461-8