Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy (Lap-DP) is one of the most accepted laparoscopic procedures in the field of pancreatic surgery. However, pancreatic fistula remains a major and frequent complication in Lap-DP, as in open surgery. The aim of this retrospective study is to clarify the advantages of prolonged peri-firing compression (PFC) with a linear stapler for prevention of pancreatic fistula after laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy.

Patients and methods

Incidence of pancreatic fistula in clinical levels (equivalent to grades B and C defined by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF)) was retrospectively compared between patients who underwent Lap-DP with PFC (PFC group, n = 17) and those who underwent Lap-DP without PFC (no-PFC group, n = 25).

Results

Incidence of clinical pancreatic fistula was significantly lower in the PFC group than in the no-PFC group. Consistent with the results for pancreatic fistula, peritoneal drainage period and postoperative hospital stay were shorter in the PFC group than in the no-PFC group.

Conclusions

Our data show that PFC effectively prevents pancreatic fistula and shortens postoperative hospital stay after Lap-DP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Laparoscopic surgery is widely accepted in various fields of abdominal surgery [1–5]. However, it is not yet popular for pancreatic disease, because of anatomical difficulties, long operating time, and high morbidity represented by pancreatic fistula [6]. The invention of linear staplers and other instruments has facilitated laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy (Lap-DP) [7]. However, pancreatic fistula, the major problem of pancreatic surgery, still remains significant, as in open distal pancreatectomy [8, 9].

We started Lap-DP in 1998, as previously reported [10]. With improving outcomes, use of Lap-DP is now increasing. Among a variety of technical refinements, prolonged peri-firing compression (PFC) of pancreas when using a linear stapler for severance of the pancreas seems to be particularly important to prevent pancreatic fistula. Herein, we demonstrate technical points of PFC and its outcome through a historical review of our experience.

Patients and methods

Patients

Forty-eight patients underwent Lap-DP in the Department of Surgery I, Kyushu University Hospital, Fukuoka, Japan from 1998 through September 2009. Lap-DP was approved by the appropriate review committee of Kyushu University Hospital, and met the guidelines of governmental agency. All 48 patients gave informed consent for surgical treatment of their disease. One patient underwent partial pancreatic resection instead of distal pancreatectomy. In five patients, Lap-DP was converted to open laparotomy; four of the five patients were converted to open pancreatectomy because of bleeding, and one of the five patients had pancreas too hard to be cut by stapler and was converted to open pancreatectomy using nonmechanical conventional transection method.

Lap-DP was eventually completed in 42 patients, and these patients were historically analyzed for incidence of pancreatic fistula.

Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy (Lap-DP)

Lap-DP was performed as described previously [11], with some modifications. Briefly, five trocars including a Hasson trocar were used in right semilateral position. The greater omentum was divided between the stomach and the transverse colon to reach the upper pole of the spleen. Short gastric vessels were sealed using laparoscopic coagulating shears. After detection of the pancreatic lesion, mostly by use of ultrasonography, the pancreas was removed from retroperitoneum and splenic artery was severed. Then pancreatic parenchyma and the splenic vein were transected together. In cases of splenic-vessel-preserving distal pancreatectomy, splenic artery and vein were isolated from the pancreas, and pancreatic parenchyma alone was simply transected. In cases of spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy with excision of splenic vessels as reported by Warshaw [12], short gastric arteries and veins were preserved. The separated distal pancreas was taken out through an extended incision of a trocar site. We left a closed peritoneal suction drain in every patient.

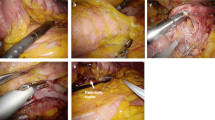

Peri-firing compression (PFC) method

We used an Echelon stapler (Echelon™ 60 ENDOPATH Stapler; Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Johnson & Johnson, Cincinnati, OH, USA) with green cartridge for PFC. PFC method was performed as follows. The pancreas was compressed directly with Echelon. After the first compression, the pancreas was kept compressed for another 3 min, and then the stapler was fired. After firing, the pancreas was kept compressed for a further 2 min. We adopted the PFC method for Lap-DP in 17 patients from April 2008 through September 2009 (PFC group). From November 1998 until March 2008, 25 patients underwent Lap-DP without PFC (no-PFC group) using Echelon or EndoGIA (EndoGIA-II 45-4.8 stapler; Tyco Healthcare, Norwalk, CT, USA). In patients in the no-PFC group, we simply precompressed the pancreas using a forceps and cut it immediately after precompression without keeping the pancreas compressed for 3 min, and did not compress the pancreas after firing except for in six patients. Six patients in the no-PFC group underwent Lap-DP with sustained 3-min compression after finishing the first compression with Echelon but without post-firing 2-min compression.

Pancreatic fistula and statistical analysis

Drains were removed when drainage amylase content became lower than three times the upper limit of normal serum amylase level, or when drainage almost dried up. Diagnosis of pancreatic fistula in clinical levels, equivalent to grade B and C defined by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF), were evaluated according to the following criteria: persistent drainage (>3 weeks), infection signs, readmission (<1 month) or fluid collection with elevated drain amylase levels (>3 × normal serum amylase), as described before [13, 14]. Chi-square statistics and Mann–Whitney U-test were used to evaluate patient characteristics and postoperative outcomes between the two groups. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

All 42 patients successfully underwent Lap-DP. Table 1 presents patient characteristics in the PFC and no-PFC groups. There were no significant differences in terms of age, gender, diabetes mellitus, prior abdominal operation or spleen preservation, as presented in Tables 1 and 2. Pathology of the resected pancreas (number of patients in the no-PFC/PFC groups) was as follows: endocrine tumor 6/3, insulinoma 1/0, mucinous cystic neoplasm 3/7, solid and pseudopapillary tumor 3/2, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm 3/3, chronic pancreatitis 6/0 (one patient with pancreatitis in the no-PFC group had concomitant pancreatic cancer), epidermoid cyst 3/0, and serous cystic neoplasm 0/2.

Pancreatic fistula

Postoperatively, seven patients (six grade B patients, one grade C patient) in the no-PFC group developed pancreatic fistula (28%), while no patients in the PFC group developed pancreatic fistula (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1A) [13]. However, two patients in the PFC and no-PFC group developed pseudocysts more than 1 month after surgery. Two patients complained of fever and lumbar back pain. Serum data showed elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), and computed tomography (CT) revealed a pseudocyst behind the stomach in both patients. One patient was successfully treated by fasting and antibiotics. The other patient underwent endoscopic transgastric stenting. CRP of the patient was improved on the day after stenting, and meals were resumed in 2 days. Including these two patients as grade B or C pancreatic fistula, incidence of pancreatic fistula becomes 32% (eight patients, seven grade B and one grade C) in the no-PFC group and 5.9% (one grade B patient) in the PFC group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1B). In the PFC group, the transected part was the body in ten patients and the tail in seven patients; one patient who underwent Lap-DP at the body developed delayed pseudocyst (10%, p = 0.39), as mentioned above.

Peri-firing compression prevented pancreatic fistula. A Comparison of rates of pancreatic fistula between the two groups. The rate of pancreatic fistula in the no-PFC and PFC group was 28 and 0%, respectively (p < 0.05). B Comparison of rates of pancreatic fistula, including patients who developed pseudocysts more than 1 month after surgery, between the two groups. The rate of pancreatic fistula in the no-PFC and PFC group was 32 and 5.9%, respectively (p < 0.05)

Furthermore, we compared incidence of pancreatic fistula in relation to texture and transection position (Table 3), with no statistically significant differences detected in our series.

Finally, we analyzed incidence of pancreatic fistula in relation to the staplers used in the no-PFC group. Without the PFC method, incidence of pancreatic fistula using Echelon 60 (13 patients) and EndoGIA (12 patients) was 23.1 and 33.3%, respectively, with no statistically significant difference (p = 0.57).

Perioperative outcomes

Consistent with the results for pancreatic fistula, the peritoneal drainage period in the PFC group (5 days) was significantly (p < 0.05) shorter than that in the no-PFC group (11.5 days), as shown in Table 4. Median postoperative hospital stay was also shorter in the PFC group (13 days) than in the no-PFC group (17 days, p < 0.05, Table 4). There were no differences in median time to meal resumption (7.5 and 8 days, respectively, Table 4).

Discussion

We have demonstrated that our simple method was useful for preventing pancreatic fistula in laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. PFC has shown clinical benefits of pancreatic fistula prevention, shorter drainage period, and shorter hospital stay. However, time to meal resumption did not show a significant difference between the two methods. Lap-DP preserves the duodenum, which is the main source of intestinal hormones, and the influence of intestinal hormones on amylase secretion may be more significant in Lap-DP than in pancreatoduodenectomy. This is one of the reasons why resumption of regular meals after Lap-DP is slightly delayed (8 days) in our department. Another reason may be the method of treating pseudocysts. When a patient has developed a pseudocyst after drain removal, the patient is easily treated by endoscopic transgastric stenting. Patients with pseudocyst are able to start meals within 2 days after placement of the stent.

Pancreatic fistula is the most serious and frequent complication of distal pancreatectomy in both laparoscopic and open methods [6]. Yamaguchi et al. [15] and Sugiyama et al. [16] suggested that transection of pancreatic ductules on the cut surface of the pancreas is one of the risks for pancreatic fistula in pancreatoenterostomy. This mechanism was applied to the development of pancreatic fistula in distal pancreatectomy in a previous report [7]. The mechanical stapling method, which is able to seal pancreatic ductules, should be advantageous compared with the conventional method of ligating the main pancreatic duct. Consistent with this hypothesis, some devices have been reported to be effective for preventing pancreatic fistula in open distal pancreatectomy, i.e., the TA-55 stapler (Tyco Healthcare) [17], GIA-80 stapler (Tyco Healthcare) [18], Endo GIA stapler (Tyco Healthcare) [19], and Endo SGIA stapler [7]. However, incidence of pancreatic fistula varied, and the precise advantages of these devices remain controversial. Furthermore, incidences of pancreatic fistula in open and laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy are often reported to be similar [6, 10, 20]. Our data without PFC also showed a similar rate of pancreatic fistula to open distal pancreatectomy, as reported previously [21]. Okano et al. [22] achieved low fistula incidence using the Echelon 60 stapler, although we did not detect any statistical difference between GIA and Echelon without PFC.

The staple is a slender and sharp metallic line, not a soft and broad cloth, and the pancreas is an extremely fragile organ [7]. These facts suggest that parenchyma of the pancreas easily tears with staples, which may further injure pancreatic ductules. This mechanism may decrease the expected effect of the mechanical stapler on distal pancreatectomy. Our PFC method was able to flatten the pancreas by compressing it as much as possible, preventing injury. Consistent with our hypothesis, Morita et al. [23] experimentally proved that pre-firing compression is useful for decreasing the amount of tissue in intestinal anastomosis using swine intestine.

Six patients in the no-PFC group underwent Lap-DP with sustained 3-min compression after precompression with Echelon, but without post-firing 2-min compression. We did not experience any symptomatic pancreatic fistula during the hospital stay after surgery without compression after firing. However, two patients subsequently developed symptomatic pancreatic pseudocyst and needed readmission. We estimate that these cysts were caused by presence of sustained minor pancreatic fistula. We have shown that the PFC group showed a significantly lower rate of pancreatic fistula than the no-PFC group, even when late-developing (>30 days after surgery) pseudocysts are included. These facts suggest that compression both before and after firing might be important. The Echelon stapler has two compression mechanisms: precompression and parallel compression. The parallel mechanism compresses the pancreas during firing, and the distance between the two jaws of the stapler becomes shortest just after the completion of firing. The importance of compression before and after firing may be due to this mechanism.

In our series, we did not detect statistically significant differences in incidence of pancreatic fistula in regard to pancreas texture. However, one patient was converted to open pancreatectomy because of pancreas texture too hard to be cut by the stapler. This suggests that pancreas with hard texture is not suitable for resection by stapler. Incidence of pancreatic fistula was not significantly different between transection of different parts of the pancreas, i.e., body versus tail, suggesting that the green cartridge, the thickest of the Echelon stapler cartridges, is not too thick to cut the pancreatic tail.

Conclusions

The PFC method offers significant advantage in preventing pancreatic fistula after laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. We are now adopting PFC in open surgery as well as in laparoscopic surgery. Large-scale randomized study may be needed to clearly document the advantage of PFC.

References

Tanaka M, Shimizu S, Mizumoto K, Yokohata K, Chijiiwa K, Yamaguchi K, Ogawa Y (2001) Laparoscopically assisted resection of choledochal cyst and Roux-en-Y reconstruction. Surg Endosc 15(6):545–552

Ogawa T, Shimizu S, Mizumoto K, Uchiyama A, Yokohata K, Chijiiwa K, Tanaka M (2001) Comparison of laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy in patients with cardiac valve replacement. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 8(2):158–160

Shimizu S, Yokohata K, Mizumoto K, Yamaguchi K, Chijiiwa K, Tanaka M (2002) Laparoscopic choledochotomy for bile duct stones. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 9(2):201–205

Noshiro H, Shimizu S, Nagai E, Ohuchida K, Tanaka M (2003) Laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: is it beneficial for patients of heavier weight? Ann Surg 238(5):680–685

Shimizu S, Nakashima N, Okamura K, Hahm JS, Kim YW, Moon BI, Han HS, Tanaka M (2006) International transmission of uncompressed endoscopic surgery images via superfast broadband Internet connections. Surg Endosc 20(1):167–170

Kim SC, Park KT, Hwang JW, Shin HC, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH, Han DJ (2008) Comparative analysis of clinical outcomes for laparoscopic distal pancreatic resection and open distal pancreatic resection at a single institution. Surg Endosc 22(10):2261–2268

Misawa T, Shiba H, Usuba T, Nojiri T, Uwagawa T, Ishida Y, Ishii Y, Yanaga K (2008) Safe and quick distal pancreatectomy using a staggered six-row stapler. Am J Surg 195(1):115–118

Sheehan MK, Beck K, Creech S, Pickleman J, Aranha GV (2002) Distal pancreatectomy: does the method of closure influence fistula formation? Am Surg 68(3):264–267 discussion 267–268

Knaebel HP, Diener MK, Wente MN, Buchler MW, Seiler CM (2005) Systematic review and meta-analysis of technique for closure of the pancreatic remnant after distal pancreatectomy. Br J Surg 92(5):539–546

Shimizu S, Tanaka M, Konomi H, Mizumoto K, Yamaguchi K (2004) Laparoscopic pancreatic surgery: current indications and surgical results. Surg Endosc 18(3):402–406

Shimizu S, Tanaka M, Konomi H, Tamura T, Mizumoto K, Yamaguchi K (2004) Spleen-preserving laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy after division of the splenic vessels. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 14(3):173–177

Warshaw AL (1988) Conservation of the spleen with distal pancreatectomy. Arch Surg 123(5):550–553

Pratt WB, Maithel SK, Vanounou T, Huang ZS, Callery MP, Vollmer CM Jr (2007) Clinical and economic validation of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) classification scheme. Ann Surg 245(3):443–451

Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M (2005) Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery 138(1):8–13

Yamaguchi K, Chijiwa K, Shimizu S, Yokohata K, Tanaka M (1998) Litmus paper helps detect potential pancreatoenterostomy leakage. Am J Surg 175(3):227–228

Sugiyama M, Abe N, Izumisato Y, Tokuhara M, Masaki T, Mori T, Atomi Y (2001) Pancreatic transection using ultrasonic dissector in pancreatoduodenectomy. Am J Surg 182(3):257–259

Pachter HL, Pennington R, Chassin J, Spencer FC (1979) Simplified distal pancreatectomy with the Auto Suture stapler: preliminary clinical observations. Surgery 85(2):166–170

Kajiyama Y, Tsurumaru M, Udagawa H, Tsutsumi K, Kinoshita Y, Akiyama H (1996) Quick and simple distal pancreatectomy using the GIA stapler: report of 35 cases. Br J Surg 83(12):1711

Takeuchi K, Tsuzuki Y, Ando T, Sekihara M, Hara T, Kori T, Nakajima H, Kuwano H (2003) Distal pancreatectomy: is staple closure beneficial? ANZ J Surg 73(11):922–925

Palanivelu C, Shetty R, Jani K, Sendhilkumar K, Rajan PS, Maheshkumar GS (2007) Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: results of a prospective non-randomized study from a tertiary center. Surg Endosc 21(3):373–377

Kuroki T, Tajima Y, Kanematsu T (2005) Surgical management for the prevention of pancreatic fistula following distal pancreatectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 12(4):283–285

Okano K, Kakinoki K, Yachida S, Izuishi K, Wakabayashi H, Suzuki Y (2008) A simple and safe pancreas transection using a stapling device for a distal pancreatectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 15(4):353–358

Morita K, Tokunou K, Hiraki S, Kudo A, Fukuda S, Masaaki O (2006) The effects of waiting time after clamp of a linear automatic stapling instrument in small bowel resection of a pig. JSES 11(4):461–463

Disclosures

Authors M. Nakamura, J. Ueda, H. Kohno, M.Y.F. Aly, S. Takahata, S. Shimizu, and M. Tanaka have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nakamura, M., Ueda, J., Kohno, H. et al. Prolonged peri-firing compression with a linear stapler prevents pancreatic fistula in laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. Surg Endosc 25, 867–871 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-1285-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-1285-6