Abstract

Background

Many trials have used intraesophageal manometry (IEM) to measure the adequacy of fundoplication. This pilot study aimed to assess the value of IEM in predicting postoperative dysphagia.

Methods

A series of 40 patients underwent IEM studies before operative correction of gastroesophageal reflux disease and repeat studies 3 months after the procedure. During the operation, IEM studies were undertaken before pneumoperitoneum was established, after pneumoperitoneum, after pneumoperitoneum with fundoplication, and after fundoplication without pneumoperitoneum. All the patients were followed up 1, 6, and 12 months after the procedure for assessment to detect persistent reflux and postfundoplication dysphagia.

Results

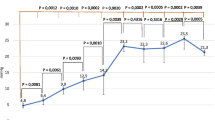

Three patients demonstrated persistent dysphagia at the 12-month follow-up point. No statistically significant differences in preoperative manometry findings were observed in the dysphagic and nondysphagic groups, with the dysphagic group showing higher pressures. However, at the operation, statistically significant differences in the lower esophageal sphincter pressures were observed after anesthesia and no pneumoperitoneum (30.3 vs. 13.4 cm H2O; p = 0.002), after anesthesia with pneumoperitoneum (40.3 vs. 18.3 cm H2O; p < 0.001), and after fundoplication with pneumoperitoneum (47.3 vs. 23.4 cm H2O; p = 0.001). No statistically significant differences were demonstrated in postoperative manometry at the 3-month follow-up point.

Conclusion

Intraoperative manometry may be a useful tool compared with postoperative manometry in identifying patients who may experience postfundoplication dysphagia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Mild reflux may be managed with proton pump inhibitors, but surgery is accepted as the “gold standard” treatment for moderate to severe gastroesophageal reflux [1]. Numerous operative procedures have been described including Nissen, Lind, and anterior and posterior fundoplication, all of which can be undertaken using either a laparoscopic or an open technique.

A major problem associated with antireflux surgery is the potential for postoperative dysphagia. Many trials have aimed to establish a pattern or potential methods for identifying patients at risk for the development of these symptoms.

Unfortunately, dysphagia is a common occurrence after fundoplication, and its pathophysiology still is relatively poorly understood. Studies of individuals with preexisting motility disorders have failed to demonstrate adverse outcomes even when a Nissen fundoplication is used [2]. This is reiterated in other studies that have failed to demonstrate useful criteria by which postfundoplication dysphagia can be anticipated [3].

This pilot study aimed to determine whether postoperative dysphagia can be predicted by using intraoperative manometry at various stages of the operation.

Patients and methods

The study protocol was approved by the South Sheffield Research Ethics Committee, and the study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association declaration of Helsinki (revised 1989).

After establishment of anesthesia, an eight-lumen water-perfused catheter (Oakfield Instruments Ltd., Oxford, England) was placed into the esophagus of the patient via the nose. The catheter was attached to a Flexiolog 3000 data-logger (Oakfield Instruments Ltd.), which in turn was connected to a portable pneumohydraulic pump (Oakfield Instruments Ltd.). Gastric pressure, the location and resting pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter (or high-pressure zone after fundoplication), and esophageal body pressure were obtained using the station pull-through technique.

Manometry readings then were undertaken at predetermined intervals: after anesthesia with no pneumoperitoneum, after anesthesia with pneumoperitoneum, after fundoplication with pneumoperitoneum, and after fundoplication with no pneumoperitoneum. Laparoscopic fundoplications were performed as described previously [4, 5].

After introduction of the laparoscope, a brief inspection was performed to identify any hiatal hernia or adhesions. These then were subsequently graded. Intraoperative problems and the requirement for conversion to open surgery then were noted. A standardized procedure was followed, and any reason for variation was documented.

Anterior fundoplication began with dissection of the hiatal pillars, followed by full esophageal mobilization and posterior hiatal repair using a mean of two sutures. A tape was placed around the esophagus to assist with esophageal retraction, and the short gastric arteries were not divided. In anterior fundoplication, the fundus of the stomach was brought across the front of the lower esophagus and sutured first to the right side of the esophagus and then to the right crus.

Lind fundoplication began with dissection of the hiatal pillars, followed by full esophageal mobilization and posterior hiatal repair. A tape was placed around the esophagus to assist with esophageal retraction, and the short gastric vessels were not divided. No bougie was used. A “bare” area was left between the anterior and posterior fundal wraps, resulting in a 270° to 300° wrap being formed using six sutures (3 on each side).

Oral fluids were started the evening after surgery. Then, if tolerated, a soft diet was allowed the next day. Discharge from the hospital was allowed when the patient was stable and able to manage at home. Dietary advice given to the individuals instructed them not to eat bread or lumpy foods for the first 4 weeks.

At their initial enrollment in the trial, the patients were interviewed by an experienced consultant surgeon (R.A.). Questions were asked using a standard, structured questionnaire. Subsequent clinical appointments were undertaken by an experienced clinician 1, 6, and 12 months after the procedure using the same questionnaire format. The patients ranked the outcome of surgery on whether they still had reflux symptoms or dysphagia.

Stationary esophageal manometry, including the response to several swallows of water and ambulatory pH monitoring, was undertaken before operative intervention, during the procedure, and approximately 3 months after the procedure. A standardized procedure was closely followed. The patients were fasted for 6 h before the pH and manometry studies. A single-use antimony crystal probe (Mediplus, High Wycombe, UK) was positioned 5 cm above the lower esophageal sphincter and connected to a Flexilog 2000 data-logger (Oakfield Instruments, Whitney, UK) [6]. The total number of reflux episodes and the percentage of time the pH was lower than 4 were recorded.

Before manometry was performed, all the individuals were asked to cease medication known to affect esophageal motility. Esophageal wave amplitude and propagation were measured by ten 10-ml water bolus swallowings 30 s apart. All readings obtained were in cm H2O.

Statistical analysis

The main outcome measures used in this trial were postoperative symptoms. The values presented are means, and where appropriate, confidence intervals and standard deviations are provided. Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows, version 15 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The following tests were used to assist analysis: Chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, and Mann–Whitney U test. A p value less than 0.050 was assumed to indicate statistical significance.

Results

The study recruited and enrolled 40 patients (20 woman and 20 men) ranging in age from 20 to 78 years (mean, 48 years). The duration of symptoms ranged from 1.5 to 28 years (mean, 8 years).

Of the 40 patients recruited, 39 underwent laparoscopic fundoplication. For the remaining patient, the procedure was cancelled due to poor lung function. Of these patients, 28 underwent Lind fundoplication, and 11 had anterior fundoplication. Manometric data were collected for all the patients preoperatively, intraoperatively, and postoperatively (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6).

Two patients were excluded from the study because their procedure was converted to open fundoplication, and four patients were excluded due to equipment malfunction. Three patients demonstrated persistent dysphagia at the 12-month follow-up point. The preoperative manometry studies showed no statistically significant differences between the dysphagic and nondysphagic groups, although the dysphagic group had higher esophageal body pressure (p = 0.299), sphincter pressure (p = 0.997), and gastric pressure (p = 0.958).

However, at the operation, the lower esophageal sphincter pressures showed the following statistically significant differences: after anesthesia and no pneumoperitoneum (30.3 vs. 13.4 cm H2O; p = 0.002), after anesthesia with pneumoperitoneum (40.3 vs. 18.3 cm H2O; p < 0.001), and after fundoplication with pneumoperitoneum (47.3 vs. 23.4 cm H2O; p = 0.001). At the 3-month follow-up point, no statistically significant differences in postoperative manometry were demonstrated for esophageal body pressure (p = 0.870), sphincter pressure (p = 0.172), or gastric pressure (p = 0.227).

Three patients had persistent reflux symptoms at 12 months. There were no significant differences in the sphincter pressures of the patients with reflux compared with the asymptomatic patients. The only demonstrable statistical difference was in the gastric pressure after anesthesia with pneumoperitoneum. For patients with persistent reflux, this pressure was 16.38 cm H2O compared with 5.75 cm H2O (p = 0.046).

Discussion

Although proton pump inhibitors are the treatment of choice for patients with mild gastroesophageal reflux disease, the gold standard management for gastroesophageal reflux disease is considered to be laparoscopic fundoplication. There is an increasing trend to offer patients surgical correction for reflux disease at earlier stages of the disease.

Dysphagia is a common occurrence after fundoplication, and its pathophysiology still is relatively poorly understood. Studies undertaken to investigate individuals with preexisting motility disorders have failed to demonstrate adverse outcomes even when a Nissen fundoplication is used [2], and this is reiterated in other studies that have failed to demonstrate useful criteria by which postfundoplication dysphagia can be anticipated [3].

The forerunning hypotheses in current literature are that postfundoplication dysphagia is due to a change in esophageal motor function or gastroesophageal junction characteristics. Myers et al. [7] conducted a study based on esophageal manometry. Patients were placed into two groups: one group to undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy and another group to undergo laparoscopic fundoplication. The procedures were undertaken, and esophageal manometry was performed on postoperative day 1. This demonstrated grossly disturbed esophageal motility after fundoplication, which was absent in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy group, indicating the occurrence of “esophageal ileus.”

The literature on the value of intraoperative manometry for the prediction of postfundoplication dysphagia is limited. Numerous published studies have used intraoperative manometry in the formation of the fundoplication wrap [8, 9], but no studies have used it for predicting postoperative dysphagia. Hill [10] performed intraoperative manometry for 200 patients with gastroesophageal reflux. The lower esophageal sphincter pressure was measured at various intervals including before and during repair. The intraoperative pressures were approximately 50 mmHg, and the postoperative pressures ranged from 15 to 25 mmHg. No patients with sphincter pressures higher than 15 mmHg demonstrated reflux according to postoperative pH and pressure studies. The authors concluded that measurement of intraoperative sphincter pressure is a safe, simple, and reliable technique that should be standard procedure for all operations on the gastroesophageal junction.

Manometry measures pressure within the esophageal lumen and sphincters to provide an assessment of the neuromuscular activity that dictates function in health and disease. It is performed to investigate the cause of functional dysphagia and unexplained noncardiac chest pain. It also is used in the preoperative workup of patients referred for antireflux surgery [11].

The main finding in our study was the presence of abnormally high lower esophageal sphincter pressures in the dysphagic patients. Surprisingly, the difference in these pressures became apparent only after anesthesia. The patients who had adequate control of reflux and no symptoms of dysphagia had lower esophageal sphincter pressure readings of about 20 cm H2O during the intraoperative period. However, at the 3-month manometry study point, no significant difference was observed between the nondysphagic (21.9 cm H2O) and dysphagic (27.3 cm H2O) (p = 0.172) groups.

Given the aforementioned findings, intraoperative manometry may be a useful tool in both the prediction and prevention of dysphagia for patients who undergo fundoplication. However, a spectrum of opinion can be found in the current literature. Del Genio et al. [12] undertook a retrospective analysis of 309 functional surgical procedures on the esophagus that used intraoperative manometry and found it to be a useful tool for detecting the high-pressure zone and for calibrating lower esophageal sphincter pressure. Prochazka et al. [9] also concluded that intraoperative manometry may prove beneficial in predicting persistent postoperative dysphagia.

Orringer et al. [13] undertook a study of 45 patients who underwent a Collis-Nissen fundoplication and had several peri- and intraoperative manometric studies. They concluded that esophageal mobilization resulted in variable intraoperative high-pressure zone values and was not a reliable predictor of postoperative high-pressure zones.

In summary, intraoperative manometry may prove to be beneficial in predicting postoperative dysphagia. However, serial measurements at various stages of the operative procedure ranging from induction of anesthesia to completion of the operation must be undertaken. With the advent of high-resolution manometry [11], the complex functional anatomy of the esophageal high-pressure zone may be studied more closely during these stages.

References

Catarci M, Gentileschi P, Papi C et al (2004) Evidence-based appraisal of antireflux fundoplication. Ann Surg 239:325–337

Baigrie RJ, Watson DI, Myers JC, Jamieson GG (1997) Outcome of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication in patients with disordered preoperative peristalsis. Gut 40:381–385

Bessell J, Adair WD, Smithers BM, Martin I, Menzies B, Gotley DC (2002) Early reoperation for acute dysphagia following laparoscopic fundoplication. Br J Surg 89:783–786

Munro A (2000) Laparoscopic anterior fundoplication. J R Coll Surg Edinb 45:93–98

Dallemagne B (2005) Laparoscopic posterior 180° fundoplication for major dysphagia after Nissen procedure, vol 5. WeBSurg.com

Ackroyd R, Watson DI, Majeed AW, Troy G, Treacy PJ, Stoddard CJ (2004) Randomised clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open fundoplication for gastro-oesophageal disease. Br J Surg 91:975–982

Myers J, Jamieson GG, Wayman J, King DR, Watson DI (2007) Esophageal ileus following fundoplication. Dis Esophagus 20:420–427

Slim K, Boulant J, Pezet D et al (1996) Intraoperative esophageal manometry and fundoplications: prospective study. World J Surg 20:55–59

Prochazka V, Kala Z, Kroupa R et al (2005) Could the peroperative manometry of the oesophagus be used for the prediction of dysphagia following antireflux procedures? Rozhledy V Chirurgi 84:7–12

Hill L (1978) Intraoperative measurement of lower esophageal sphincter pressure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 75:378–382

Fox M, Bredenoord AJ (2008) Oesophageal high-resolution manometry: moving from research into clinical practice. Gut 57:405–423

Del Genio A, Izzo G, Di Martino N et al (1997) Intraoperative esophageal manometry: our experience. Dis Esophagus 10:253–261

Orringer M, Schneider R, Williams GW, Sloan H (1980) Intraoperative esophageal manometry: is it valid? Ann Thoracic Surg 30:13–18

Disclosures

M. Khan, A. Smythe, K. Elghellal, and R. Ackroyd have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, M., Smythe, A., Elghellal, K. et al. Can intraoperative manometry during laparoscopic fundoplication predict postoperative dysphagia?. Surg Endosc 24, 2268–2272 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-0949-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-0949-6