Abstract

Background

The objective of the study was to compare the perioperative outcomes, including the operative time, length of hospital stay, and postoperative pain, of a single-port-access laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (SPA-LAVH) and conventional LAVH.

Methods

This is a retrospective case–control study. A single surgeon performed 43 SPA-LAVH (cases) between May 2008 and February 2009, and 43 conventional LAVH between September 2005 and April 2008 (controls). Data of the SPA-LAVH cases were collected prospectively into our data registry and we reviewed the data of controls on chart.

Results

The demographic parameters, except a history of vaginal delivery, were comparable between the two groups. The SPA group was associated with a history of fewer vaginal deliveries (SPA, 63%; conventional, 84%; p = 0.03). The two groups were comparable with respect to indications for surgery, failed cases from planned procedures, cases requiring additional procedures, and cases needing transfusion. The operative time, estimated blood loss (EBL), drop in hemoglobin preoperatively to postoperative day 1, and postoperative hospital stay were comparable between both groups. SPA-LAVH was associated with reduced postoperative pain. The VAS-based pain scores 24 h (SPA, 2.5 ± 0.7; conventional, 3.5 ± 0.8; p < 0.01) and 36 h after surgery (SPA, 1.7 ± 1.2; conventional, 2.9 ± 1.1; p < 0.01) were lower in the SPA group. There were no complications, including reoperation, adjacent organ damage, and any postoperative morbidity, in both groups. In addition, we have encountered no umbilical complications to date using SPA.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that SPA-LAVH has comparable operative outcomes to conventional LAVH and the postoperative pain was decreased significantly in the SPA group 24 and 36 h after surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH) has been implemented in hysterectomy procedures for uterine myomas and adenomyomas. Three or four laparoscopic ports are traditionally required to complete a LAVH. One port is inserted through the infraumbilicus, and the other ports are usually inserted through the lateral abdominal wall muscles, suprapubis, or both [1].

To minimize minimally invasive surgical techniques such as LAVH, single-port-access (SPA) laparoscopic surgery has been developed [2–4]. The main advantage of SPA surgery is the excellent cosmetic outcome. This approach requires only one umbilical incision; therefore, the surgical scar can be hidden within the umbilicus, making the surgery virtually scarless. In addition to the potential cosmetic benefit, other theoretical advantages of SPA surgery compared to conventional laparoscopy include less postoperative pain and a faster recovery. On the other hand, SPA surgery is believed to need a longer operative time compared to conventional laparoscopy because of the technical challenges in surgical procedures. However, a comparison of these variables has yet to be reported. In this study, we attempted to better define the potential benefits of SPA surgery by reporting our comparative experience between SPA-LAVH and conventional LAVH.

Materials and methods

This study was a retrospective case–control study comparing one surgeon’s experiences with 43 SPA-LAVHs (cases) performed between May 2008 and February 2009 and 43 conventional LAVHs (controls) performed between September 2005 and April 2008. On 16 May 2008, SPA-LAVH was introduced to our hospital by a gynecologic surgeon (TJK). Since then, he has performed SPA-LAVH on all patients with symptomatic myomas and/or adenomyosis without selection. The data for these patients were collected prospectively after approval by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center, Korea. For the control group, we retrospectively investigated 43 consecutive patients who underwent conventional LAVH for symptomatic myomas and/or adenomyosis by the same surgeon from the time of the introduction of SPA surgery without selection.

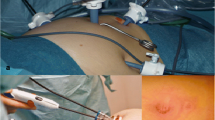

The operative procedures were not different between the two groups with the exception of port placement (Fig. 1). For conventional LAVH we usually used three ports (one 12-mm trocar in the infraumbilicus and two 5-mm trocars in lateral abdominal walls). Herein, we describe the SPA-LAVH techniques in detail. The patient was placed in the dorsal lithotomy position. A uterine manipulator was inserted to effectively make a surgical field. A 1.5-2.0-cm vertical incision was made within the umbilicus. A small wound retractor (ALEXIS®, Applied Medical, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA, USA) was inserted into the wound opening transumbilically. Once the wound retractor was fixed in the opening site, it laterally retracted the sides of the wound opening, thus making the small vertical incision into a wider, rounder opening. A surgical glove with three sheaths that were inserted through the cut edges of the distal finger tips and tied with an elastic bandage to prevent leakage of carbon dioxide was draped around the rim of the wound retractor. The elasticity of the glove enables it to achieve an airtight seal, thus maintaining the pneumoperitoneum. The multiple fingers of the glove function as multiports for laparoscopic instruments and a scope.

We used a 5-mm, 0° rigid laparoscope and an articulating instrument (Roticulator®, Covidien, Norwalk, CT, USA) to avoid clashing of the instruments and to optimize the range of motion. The ovarian ligaments, round ligament, and broad ligament were dissected with a 45-mm Endo-GIA® (a single-use loading unit with titanium staples developed by Covidien). When the ligaments were dissected bilaterally and the bleeding was controlled, we began the vaginal approach. After all procedures were completed, skin adhesive was used to close the skin because of its good cosmetic effects and patient convenience for the SPA group (Fig. 2). For the SPA group, the uterine weight was measured immediately after the specimen was removed in the operating room. All of the patients hemoglobin levels were measured on postoperative day 1. A Foley vesical catheter was maintained until the morning of the first day after surgery. Patients were discharged when they were tolerating a diet.

Demographic information, uterine size, operative indication, final pathology, operative time (from skin incision to skin closure), additional procedures, EBL, failed cases, transfusion requirements, change in serum hemoglobin (%), postoperative hospital stay, and postoperative pain score by visual analog scale (VAS) were recorded. For the SPA group, data were collected prospectively; for the conventional group, data were obtained by chart review.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v15.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Comparisons between groups were performed with Student’s t test for continuous data, and χ2 analyses, including Fischer’s exact test, for nominal data. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, and all reported p values are two-sided.

Results

Eighty-six patients were included in this study: 43 patients underwent SPA-LAVH and 43 patients underwent conventional LAVH (Table 1). There were 68 cases with uterine myomas and 18 cases with adenomyosis. All patients had symptoms related to these diagnoses, such as menorrhagia (51%), dysmenorrhea (24%), and pelvic pressure or urinary frequency (24%). Demographic parameters, except a history of vaginal delivery, were comparable between the two groups. Patients in the SPA group had fewer vaginal deliveries (SPA, 63%; conventional, 84%; p = 0.03). The two groups were comparable with respect to indications for surgery, failed cases from planned procedures, cases requiring additional procedures, and cases that required transfusion. We did not measure the real uterine weight of the conventional group so we used the size of the uterus on sonographic scans for comparison. The uterine size was also comparable between both groups.

We excluded six failed cases (4 for the SPA and 2 for the conventional group) in the analysis of the operative time, blood loss, postoperative pain, and hospital stay (Table 2). Three patients in the SPA group needed additional trocar(s) (one trocar for two patients and two trocars for the other patient). Therefore, these patients underwent the same procedure as the conventional LAVH except they had a larger umbilical wound. The operative time, EBL, drop in hemoglobin level preoperatively to postoperative day 1, and the postoperative hospital stay were comparable between both groups.

SPA-LAVH was associated with reduced postoperative pain (Fig. 3). VAS-based pain scores 24 h (SPA, 2.5 ± 0.7; conventional, 3.5 ± 0.8; p < 0.01) and 36 h (SPA, 1.7 ± 1.2; conventional, 2.9 ± 1.1; p < 0.01) after surgery were lower for the SPA group. However, the pain scores 12 h after surgery were not different between the groups.

There were no complications, including reoperation, adjacent organ damage, and postoperative morbidity, in both groups. In addition, we encountered no umbilical complications to date using SPA.

Discussion

The results of this study show that the operative outcomes, including operative time, hospital stay, and EBL, in the SPA-LAVH group were comparable to those of the conventional LAVH group. In addition, pain after surgery was lower in the SPA group than in the conventional group.

The SPA technique has been improved [5, 6] and might be adequate for gynecologic surgery [7–11]. This technique is expected to be popular in the near future because surgeons can perform scarless surgery with minimal modifications of current methods. To advance the SPA technique, it is proper to compare perioperative outcomes between SPA and the conventional method. This study is the first to compare the operative outcomes between SPA and conventional laparoscopy in gynecological procedures.

This case–control study has some strong points: We minimized the selection bias by using 86 consecutive patients who planned to undergo conventional or SPA-LAVH for symptomatic myomas and/or adenomyosis. The surgical technique was standardized because all operations were done by one surgeon.

We achieved a high success rate with LAVH via a single port (91%) and the conventional method (95%). The SPA group had more patients with a history of previous abdominal surgery, including cesarean delivery, which might be one of the obstacles in performing laparoscopy. When we take this into the consideration, SPA-LAVH is manageable and not challenging compared to conventional LAVH.

We observed that the operation time was similar for both groups. This makes sense because the main procedure of LAVH is the vaginal approach. Thus, the operative time was not affected by the scope phase when performing LAVH by either the SPA or the conventional method.

The differences in postoperative pain at 24 and 36 h after surgery between the two groups, which were statistically significant, showed the potential benefit of SPA surgery and may be the reason for the shorter hospital stay for SPA patients. This could be explained by the smaller number of skin wounds or the shorter total length of the skin incision [1]. In the SPA group, the only skin wound was in the umbilicus which has no muscle layer beneath the skin. This relatively tension-free umbilical wound in the SPA procedure could cause less pain than the three or four wounds used in the conventional method, including the abdominal side wall incision that could cause more pain due to muscle layers under the skin. Furthermore, less postoperative pain in the SPA group also might be explained by reduced bruising of the abdominal musculature because of the elimination of transmuscular placement of the traction ports. However, 12 h after surgery the pain score between the two groups was not statistically different. This might be because patients of both groups were in bed right after surgery so visceral pain would be similar regardless of the abdominal skin incision and would be more dominant in both groups at that period of time.

This study has its limitations. First, it was designed retrospectively. Second, we selected historic patients all treated by the same surgeon as a control group. The cases and controls were divided by the specific time; therefore, we cannot take into account the learning curve of the surgeon. Third, in analyzing the difference in pain between groups, analgesic requests, which must be an important confounder, should have been considered. Further prospective trials that take analgesic usage into consideration are warranted. Fourth, this study was focused on hysterectomy using SPA. Other gynecologic pelviscopic surgeries on ovarian tumors, such as oophrectomy and cystectomy, could be a different matter. Fifth, because we have no experience with other SPA systems, it is unclear whether all SPA systems have comparable and beneficial outcomes compared with conventional methods. Our SPA system using the surgical glove may offer more flexibility of manipulation of the trocars than other rigid single-port systems. As a result, different operative outcomes from different SPA systems can occur.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that SPA-LAVH has comparable operative outcomes to conventional LAVH and postoperative pain was decreased significantly in the SPA group at 24 and 36 h after surgery.

References

Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Colombo G, Uccella S, Bergamini V, Serati M, Bolis P (2005) Minimizing ancillary ports size in gynecologic laparoscopy: a randomized trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 12:480–485

Esposito C (1998) One-trocar appendectomy in pediatric surgery. Surg Endosc 12:177–178

Kaouk JH, Haber GP, Goel RK, Desai MM, Aron M, Rackley RR, Moore C, Gill IS (2008) Single-port laparoscopic surgery in urology: initial experience. Urology 71:3–6

Piskun G, Rajpal S (1999) Transumbilical laparoscopic cholecystectomy utilizes no incisions outside the umbilicus. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 9:361–364

Canes D, Desai MM, Aron M, Haber GP, Goel RK, Stein RJ, Kaouk JH, Gill IS (2008) Transumbilical single-port surgery: evolution and current status. Eur Urol 54:1020–1029

Romanelli JR, Earle DB (2009) Single-port laparoscopic surgery: an overview. Surg Endosc 23:1419–1427

Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Fasola M, Bolis P (2005) One-trocar salpingectomy for the treatment of tubal pregnancy: a ‘marionette-like’ technique. BJOG 112:1417–1419

Kosumi T, Kubota A, Usui N, Yamauchi K, Yamasaki M, Oyanagi H (2001) Laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy using a single umbilical puncture method. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 11:63–65

Lee YY, Kim TJ, Kim CJ, Kang H, Choi CH, Lee JW, Kim BG, Lee JH, Bae DS (2009) Single-port access laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy: a novel method with a wound retractor and a glove. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 16(4):450–453

Lim MC, Kim TJ, Kang S, Bae DS, Park SY, Seo SS (2010) Embryonic natural orifice transumbilical endoscopic surgery (E-NOTES) for adnexal tumors. Surg Endosc 24 [Epub ahead of print]

Pelosi MA, Pelosi MA III (1991) Laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy using a single umbilical puncture. N J Med 88:721–726

Disclosures

Drs. Tae-Joong Kim, Yoo-Young Lee, Hyun Hwa Cha, Chul-Jung Kim, Chel Hun Choi, Jeong-Won Lee, Duk-Soo Bae, Je-ho Lee, and Byoung-Gie Kim have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

T.-J. Kim and Y.-Y. Lee contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, TJ., Lee, YY., Cha, H.H. et al. Single-port-access laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy versus conventional laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy: a comparison of perioperative outcomes. Surg Endosc 24, 2248–2252 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-0944-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-0944-y