Abstract

Introduction

Open esophagectomy for cancer is a major oncological procedure, associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Recently, thoracoscopic procedures have offered a potentially advantageous alternative because of less operative trauma compared with thoracotomy. The aim of this study was to utilize meta-analysis to compare outcomes of open esophagectomy with those of minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) and hybrid minimally invasive esophagectomy (HMIE).

Methods

Literature search was performed using Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar databases for comparative studies assessing different techniques of esophagectomy. A random-effects model was used for meta-analysis, and heterogeneity was assessed. Primary outcomes of interest were 30-day mortality and anastomotic leak. Secondary outcomes included operative outcomes, other postoperative outcomes, and oncological outcomes in terms of lymph nodes retrieved.

Results

A total of 12 studies were included in the analysis. Studies included a total of 672 patients for MIE and HMIE, and 612 for open esophagectomy. There was no significant difference in 30-day mortality; however, MIE had lower blood loss, shorter hospital stay, and reduced total morbidity and respiratory complications. For all other outcomes, there was no significant difference between the two groups.

Conclusion

Minimally invasive esophagectomy is a safe alternative to the open technique. Patients undergoing MIE may benefit from shorter hospital stay, and lower respiratory complications and total morbidity compared with open esophagectomy. Multicenter, prospective large randomized controlled trials are required to confirm these findings in order to base practice on sound clinical evidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Wit increasing experience and skills at performing laparoscopic and thoracoscopic surgery in the past decade, minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) is increasingly being used for surgical management of esophageal cancer. By the early 1990 s, some institutions had developed and utilized protocols for thoracoscopic esophagectomy, initially restricting its use to T1 and T2 esophageal tumors without neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy [1–3]. However, with time, indications for thoracoscopic esophagectomy were expanded to include more advanced cancer, irrespective of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Additionally, improvements in endoscopic surgical techniques and advances in endoscopic equipment have allowed further utilization of MIE. The techniques in minimally invasive esophageal surgery vary from totally minimally invasive to hybrid procedures where either the thoracic or the abdominal part of the operation is performed endoscopically.

Fifteen years later, minimally invasive esophagectomy has not become widespread (unlike other minimally invasive procedures). It is still considered one of the most complex gastrointestinal surgical operations, and many questions remain unanswered as to the real advantages of applying minimally invasive techniques in this particular case. Mortality, morbidity, oncological radicality, and the cost of the procedure are just some of the topics under debate. Recent reviews [4] focusing on the role of MIE have emphasized that the benefits of this approach are controversial due to the increased complexity involved. Several comparative studies [5, 6] have been conducted between open esophagectomy (OE) and minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE). Despite these studies, uncertainty about the advantages of one technique over the other persists. The question about the best approach for esophagectomy in esophageal cancer still remains unanswered.

We undertook this meta-analysis to compare MIE, hybrid minimally invasive esophagectomy (HMIE), and conventional esophagectomy. The specific questions that our study aims to answer are: (1) Is there a significant difference in 30-day mortality with MIE/HMIE as compared with OE? (2) Does MIE/HMIE reduce respiratory complications and anastomotic leaks in comparison with OE? (3) Does MIE/HMIE reduce total morbidity in comparison with OE? (4) Is MIE/HMIE oncological clearance in terms of lymph node retrieval the same as with OE? (5) Is there significant heterogeneity in the estimates of outcomes of interest between MIE/HMIE and OE?

Methods

Study selection

A Medline, Embase, Cochrane database, and Google Scholar search was performed on all clinical studies published until 2009, comparing different techniques (open, hybrid minimally invasive esophagectomy, and minimally invasive esophagectomy) for esophageal cancer. The following Mesh search headings were used: Laparoscopy, Surgical Procedures, Minimally Invasive, Thoracic Surgery, Thoracoscopy*, Laparotomy*, Gastroplasty, Thoracotomy*, Esophageal neoplasms, Esophagectomy. Only studies on humans and in English language were considered for inclusion. The related-articles function was used to expand the search from each relevant study identified. Hand-searching of the references from articles was also used. All citations and abstracts identified were thoroughly reviewed. The last date for this search was 23 January 2009.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (K.N. and K.A.) independently extracted the following data from each study: study characteristics (first author, year of publication, study design), population characteristics (number of patients included, demographics, tumor characteristics), and outcomes of interest.

HMIE and MIE

The techniques of minimally invasive surgery for esophageal disease vary widely. They include thoracoscopy combined with laparotomy, thoracoscopy combined with laparoscopy, hand-assisted thoracotomy, hand-assisted laparotomy or minilaparotomy, and laparoscopic transhiatal or hand-assisted laparoscopic transhiatal.

For our study, we classified procedures as MIE only when both abdominal and thoracic stages were either fully endoscopic or hand-assisted endoscopic, i.e., laparoscopy surgery (LS), hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (HALS), thoracoscopy surgery (TS), and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). In case of transhiatal, they were either laparoscopic transhiatal (LTH) or hand-assisted laparoscopic transhiatal (HALTH).

Procedures were classified as HMIE only when one stage (abdominal or thoracic) was open and other stage was endoscopic or hand-assisted endoscopic.

Outcomes of interest

Primary outcomes of interest were 30-day mortality and anastomotic leakage, while secondary outcomes of interest were:

-

1.

Operative outcomes: operative duration, blood loss, intensive care unit (ICU) stay, and hospital stay

-

2.

Postoperative outcomes: gastrointestinal (GI) bleed, anastomotic stricture, gastric conduit ischemia, respiratory complications, cardiac complications, chyle leak, vocal cord palsy, and total morbidity

-

3.

Oncological outcomes: lymph node retrieval (as a surrogate marker for cancer clearance)

Inclusion criteria

In order to be included in the analysis, studies had to:

-

1.

Compare the outcome measures mentioned above between open versus MIE/HMIE or HMIE versus MIE;

-

2.

Report on at least one of the outcomes of interest mentioned above.

When the same institution reported two studies, we included either the one of better quality (increased sample size) or the most recent publication.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded from analysis if:

-

1.

They were either noncomparative studies or case series;

-

2.

The outcomes of interest were not reported for the two techniques;

-

3.

There was an overlap between authors, centers or patient cohorts evaluated in the published literature.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was performed in line with recommendations from the Cochrane collaboration and Meta-analysis of Observation Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines [7]. Statistical analysis for categorical variables was carried out using the odds ratio (OR) as the summary statistic. This ratio represents the odds of an adverse event occurring in the MIE or HMIE group compared with in the open group. For continuous variables such as operative time and blood loss, statistical analysis was carried out using the weighted mean difference (WMD) as the summary statistic [8]. Data were reanalyzed using both random- and fixed-effect models. In a random-effect model it is assumed that there is variation between studies, and the calculated odds ratio thus has a more conservative value. In this research, meta-analysis using the random-effect model is preferable, particularly because patients that are operated on in different centers have varying risk profiles and techniques for esophagectomy. Analysis was conducted by using the statistical software Review Manager version 4.2 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Software Update, Oxford).

Results

Eligible studies

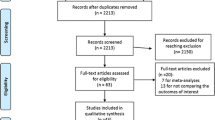

A flowchart of the literature search process is shown in Fig. 1. Twelve studies [5, 6, 9–18] were identified comparing the three techniques in question. Six [6, 9, 12, 13, 18, 19], four [5, 6, 14, 17], and three studies [10, 11, 15] compared MIE with open, HMIE with open, and MIE with HMIE, respectively. A study by Smithers et al. [5] compared both open versus MIE and open versus HMIE. On review of the data extracted, there was 100% agreement between the two reviewers. The characteristics of these 12 studies are summarized in Table 1. All studies except one utilized some form of matching criteria.

Open versus minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE)

Primary outcomes

Results from overall meta-analysis are outlined in Table 2. Using random-effects modeling, the overall results demonstrated that there was no significant difference in 30-day mortality and anastomotic leak between the two groups (P = 0.26 and P = 0.14, respectively), and no significant heterogeneity was detected between the groups in reporting these outcomes.

Subanalysis of open transthoracic (TT) and open transhiatal (TH) with MIE revealed no significant difference in 30-day mortality (P = 0.35 and P = 0.49, respectively); however, a trend towards lower anastomotic leak was found in MIE [P = 0.08, OR = 0.43, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.17, 1.10 and P = 0.09, OR = 0.46, 95% CI 0.18, 1.13].

Secondary outcomes (Figs. 2, 3, 4)

Five studies reported on operative blood loss and operative time. Blood loss was significantly lower in MIE group (P ≤ 0.001, WMD = −268.53, 95% CI −369.91, −167.16), but there was significant heterogeneity in the studies in reporting this outcome (P = 0.02).

ICU stay and hospital stay were also found to be significantly lower in patients undergoing MIE (P ≤ 0.001, WMD = −0.97, 95% CI −1.31, −0.63 and P = 0.004, WMD = −2.75, 95% CI −4.65, −0.86, respectively). In terms of postoperative outcomes, total morbidity was significantly lower in MIE group (P = 0.007, OR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.32, 0.84). Subanalysis of comorbidities revealed significant difference in respiratory complications between the two groups (P = 0.04, OR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.35, 0.98). For all other operative and postoperative outcomes, there was no significant difference between the two groups. In terms of oncological outcomes, there was no significant difference in terms of lymph nodes retrieved between the two groups.

Significant difference in blood loss and total morbidity was again found on subanalysis of open (TT) and open (TH) with MIE (P = 0.03, WMD = −486.50, 95% CI −920.99, −52.01, P < 0.001, WMD = −380.63, 95% CI −605.39, −155.87 and P = 0.03, OR = 0.54, CI 0.31–0.93, P = 0.002, OR = 0.38, CI 0.21, 0.71, respectively).

Open versus hybrid minimally invasive esophagectomy (HMIE)

Primary outcomes (Fig. 5)

Results from overall meta-analysis are outlined in Table 2. Analogous to the results of open versus MIE, there was no significant difference in 30-day mortality (P = 0.28); however, anastomotic leak was found to be significantly lower in HMIE (P = 0.02, OR = 0.51, CI 0.28, 0.91).

Secondary outcomes

There was a strong trend towards lower blood loss in HMIE group (P = 0.05, WMD = −147.87, CI = −297.40, 1.67); however, significant heterogeneity was found in the studies on reporting this outcome. Analysis of postoperative outcomes showed significantly lower respiratory complications in HMIE group (P = 0.03, OR = 0.68, CI = 0.48, 0.96), consistent with the findings of open versus MIE. There was no significant difference in reporting other outcomes.

HMIE versus MIE

Three studies were found to compare the two techniques. There was no significant difference in blood loss between the two groups (P = 0.26). Only two studies reported other outcomes, so no meta-analysis was possible for these outcomes.

Discussion

Although a decade has passed since its introduction, the efficacy of minimally invasive esophageal surgery remains unproven. This study compared outcomes between MIE, hybrid MIE, and conventional open esophagectomy (OE). The use of meta-analytic techniques allowed inclusion of a total of 478 subjects, of whom 152 (31.8%) underwent MIE and 326 (68.2%) underwent open esophagectomy. Further analysis between HMIE and open esophagectomy (OE) included 806 patients, with 520 (64.5%) patients who underwent HMIE and 286 (35.5%) who underwent open esophagectomy. A sample group of this size would be difficult to accumulate in a reasonable length of time and would require significant cost. Survival analysis could not be done as fewer than three studies in both analysis measured survival at different times (2, 3, and 5 years).

The results of this meta-analysis suggest that patients undergoing MIE had better operative and postoperative outcomes with no compromise in oncological outcomes (as assessed by lymph node retrieval). Patients receiving MIE had significantly lower blood loss, and shorter postoperative ICU and hospital stay. There was a 50% decrease in total morbidity in MIE group. Subgroup analysis of comorbidities demonstrated significantly lower incidence of respiratory complications after MIE; however, other postoperative outcomes such as anastomotic leak, anastomotic stricture, gastric conduit ischemia, chyle leak, vocal cord palsy, and 30-day mortality were comparable between the two techniques. Another subgroup analysis of MIE and open transthoracic and open transhiatal esophagectomy again confirmed significantly lower blood loss and total morbidity in patients undergoing MIE. The benefit of even one endoscopic stage in HMIE (e.g., thoracoscopy with laparotomy or thoracotomy with laparoscopy) was evident, and blood loss and respiratory complications were still found to be lower, consistent with open versus MIE analysis, thus highlighting the advantage of applying minimally invasive approach to esophagectomy. The results also establish the oncological validity of MIE; however, no conclusion can be accepted with certainty as the number of studies was small and there was significant heterogeneity in the analysis of HMIE and open esophagectomy in reporting this outcome. Although blood loss in MIE and HMIE was found to be lower compared with open, significant heterogeneity was found between the studies in reporting this outcome. This can be explained by the fact that blood loss is a very surrogate outcome, significantly dependent on operator and tumor characteristics. As seen in Table 1, although several studies were matched for age and sex, fewer were matched for tumor characteristics, which could have caused the heterogeneity between the groups.

The decrease in total morbidity and respiratory complications in the MIE group may be related to the less invasive nature of the operation, which allows improved patient mobilization following MIE, thereby facilitating recovery. However, we acknowledge that this analysis was unable to match tumor characteristics in all studies, which implies that patients with more advanced caner stage may have undergone open surgery, thereby increasing clinical heterogeneity between the groups.

Meta-analytic research such as in this study has several limitations that must be taken into account when considering its results. First, there are a lot of case series [19–24] on minimally invasive approaches to esophagectomy but no randomized controlled trials to compare. However, we should take into account that it is difficult to conduct a prospective randomized study within a reasonable timeframe. Second, it was not possible to match all patient groups for cancer stage, cancer location, and adjuvant treatment, all of which are factors known to affect outcome for patients with esophageal cancers. Third, it is important to bear in mind publication bias, particularly in secondary meta-analytic research based on published studies. Fourth, variation in inclusion criteria for minimally invasive esophagectomy including early stage of disease, treatment protocols, operative technique, and outcome assessment between studies may all influence results. Fifth, the volume–outcome effect cannot be ignored. Various reports [25–27] have shown a survival benefit in high-volume hospitals (>20 resections/year). A few of the studies in our meta-analysis failed to provide information about the volume status of their centers, so it was difficult to adjust for this factor. Finally, patients selected for minimally invasive surgery are unlikely to have been representative of the population of patients presenting to the reporting centers. Particularly in the early stages of their experience with MIE, prudent surgeons are likely to have selected patients with smaller tumors and to have avoided candidates with serious comorbidity. In addition, there is a long proficiency-gain curve [22] involved in mastering MIE, which could also have influenced the results of the studies.

Due to patient factors, tumor characteristics, and surgeon preference, randomized trials along the lines of this meta-analysis are unlikely to be feasible, thus highlighting the importance of such an analysis. Moreover, in the absence of randomized controlled trials, we believe that this meta-analysis of nonrandomized studies is useful to guide researchers towards properly informed randomization in future studies. To rule out a 50% relative risk reduction in 30-day mortality [from 6% (open) to 3% (MIE)] with a 5% significance level and 80% power, we calculated that a traditional randomized controlled trial (RCT) would require 608 patients in each arm. Similarly, to rule out a 35% relative risk reduction in anastomotic leak [from 14% (open) to 9% (MIE)] with a similar significance and power value, 566 patients would be needed in each arm for a RCT. If we include only high-volume centers (~50 esophageal resections annually) in such a trial, it would take approximately 4 years for six high-volume centers to accrue this sample size.

Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that minimally invasive approach to esophagectomy is a safe alternative to the open technique. Although there is no change in 30-day mortality, patients undergoing MIE may benefit from lower blood loss, shorter hospital stay, and reduced total morbidity and respiratory complications without compromising lymph node clearance. These results suggest some advantages of the minimal invasive approach; however, better evidence on outcomes is needed before any claims can be made for the superiority of the minimally invasive approach in normal surgical practice.

References

Akaishi T, Kaneda I, Higuchi N et al (1996) Thoracoscopic en bloc total esophagectomy with radical mediastinal lymphadenectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 112:1533–1540 (discussion 40–41)

Gossot D, Fourquier P, Celerier M (1993) Thoracoscopic esophagectomy: technique and initial results. Ann Thorac Surg 56:667–670

Kawahara K, Maekawa T, Okabayashi K et al (1999) Video-assisted thoracoscopic esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Surg Endosc 13:218–223

Wu PC, Posner MC (2003) The role of surgery in the management of oesophageal cancer. Lancet Oncol 4:481–488

Smithers BM, Gotley DC, Martin I, Thomas JM (2007) Comparison of the outcomes between open and minimally invasive esophagectomy. Ann Surg 245:232–240

Shiraishi T, Kawahara K, Shirakusa T, Yamamoto S, Maekawa T (2006) Risk analysis in resection of thoracic esophageal cancer in the era of endoscopic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 81:1083–1089

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC et al (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 283:2008–2012

DerSimonian R, Laird N (1986) Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7:177–188

Bernabe KQ, Bolton JS, Richardson WS (2005) Laparoscopic hand-assisted versus open transhiatal esophagectomy: a case-control study. Surg Endosc 19:334–337

Benzoni E, Terrosu G, Bresadola V et al (2007) A comparative study of the transhiatal laparoscopic approach versus laparoscopic gastric mobilisation and right open transthoracic esophagectomy for esophageal cancer management. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 16:395–401

Bonavina L, Bona D, Binyom PR, Peracchia A (2004) A laparoscopy-assisted surgical approach to esophageal carcinoma. J Surg Res 117:52–57

Braghetto I, Csendes A, Cardemil G, Burdiles P, Korn O, Valladares H (2006) Open transthoracic or transhiatal esophagectomy versus minimally invasive esophagectomy in terms of morbidity, mortality and survival. Surg Endosc 20:1681–1686

Fabian T, Martin JT, McKelvey AA, Federico JA (2008) Minimally invasive esophagectomy: a teaching hospital’s first year experience. Dis Esophagus 21:220–225

Law S, Fok M, Chu KM, Wong J (1997) Thoracoscopic esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Surgery 122:8–14

Martin DJ, Bessell JR, Chew A, Watson DI (2005) Thoracoscopic and laparoscopic esophagectomy: initial experience and outcomes. Surg Endosc 19:1597–1601

Nguyen NT, Follette DM, Wolfe BM, Schneider PD, Roberts P, Goodnight JE Jr (2000) Comparison of minimally invasive esophagectomy with transthoracic and transhiatal esophagectomy. Arch Surg 135:920–925

Osugi H, Takemura M, Higashino M, Takada N, Lee S, Kinoshita H (2003) A comparison of video-assisted thoracoscopic oesophagectomy and radical lymph node dissection for squamous cell cancer of the oesophagus with open operation. Br J Surg 90:108–113

Van den Broek WT, Makay O, Berends FJ et al (2004) Laparoscopically assisted transhiatal resection for malignancies of the distal esophagus. Surg Endosc 18:812–817

Nguyen NT, Roberts P, Follette DM, Rivers R, Wolfe BM (2003) Thoracoscopic and laparoscopic esophagectomy for benign and malignant disease: lessons learned from 46 consecutive procedures. J Am Coll Surg 197:902–913

Jobe BA, Kim CY, Minjarez RC, O’Rourke R, Chang EY, Hunter JG (2006) Simplifying minimally invasive transhiatal esophagectomy with the inversion approach: lessons learned from the first 20 cases. Arch Surg 141:857–865 (discussion 65–66)

Leibman S, Smithers BM, Gotley DC, Martin I, Thomas J (2006) Minimally invasive esophagectomy: short- and long-term outcomes. Surg Endosc 20:428–433

Luketich JD, Alvelo-Rivera M, Buenaventura PO et al (2003) Minimally invasive esophagectomy: outcomes in 222 patients. Ann Surg 238:486–494 discussion 94-5

Luketich JD, Schauer PR, Christie NA et al (2000) Minimally invasive esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 70:906–911 (discussion 11–12)

Peracchia A, Rosati R, Fumagalli U, Bona S, Chella B (1997) Thoracoscopic esophagectomy: are there benefits? Semin Surg Oncol 13:259–262

Begg CB, Cramer LD, Hoskins WJ, Brennan MF (1998) Impact of hospital volume on operative mortality for major cancer surgery. JAMA 280:1747–1751

Dimick JB, Wainess RM, Upchurch GR Jr, Iannettoni MD, Orringer MB (2005) National trends in outcomes for esophageal resection. Ann Thorac Surg 79:212–216 (discussion 7–8)

McCulloch P, Ward J, Tekkis PP (2003) Mortality and morbidity in gastro-oesophageal cancer surgery: initial results of ASCOT multicentre prospective cohort study. BMJ 327:1192–1197

Disclosures

Mr. Nagpal, Mr. Ahmed, Mr. Vats, Mr. Yakoub, Mr. James, Mr. Ashrafian, Dr. Darzi, Dr. Moorthy, and Dr. Athanasiou have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work has been sponsored by Elision Health Limited.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nagpal, K., Ahmed, K., Vats, A. et al. Is minimally invasive surgery beneficial in the management of esophageal cancer? A meta-analysis. Surg Endosc 24, 1621–1629 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-009-0822-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-009-0822-7