Abstract

Over the last two decades, dysphagia is increasingly recognized as a significant short-term and long-term issue in oropharyngeal cancer patients. However, there remains a lack of standardization and agreement about reporting swallowing outcomes in studies that assess treatment outcomes in this population. A systematic review was performed following PRISMA Guidelines by searching Pubmed (MEDLINE) and Scopus. The inclusion criteria used included (1) prospective and retrospective clinical studies involving adult patients with oropharyngeal cancer, (2) reports swallowing outcomes, (3) English studies or studies with English translation, (4) full text retrievable and (5) publication between 1990 and 2016. 410 unique studies were identified, and 106 were analyzed. A majority (> 80%) of studies that reported swallowing outcomes were published after 2010. While 75.4% of studies reported subjective outcomes (e.g., patient-reported or clinician-reported outcome measures), only 30.2% of studies presented results of objective instrumental assessment of swallowing. The majority (61%) of studies reported short-term swallowing outcomes at 1 year or less, and only 10% of studies examined 5-year swallowing comes. One study examined late-dysphagia (> 10 years) in the oropharyngeal cancer population. Considerable heterogeneity remains in the reporting of swallowing outcomes after treatment of oropharyngeal cancer despite its importance for quality of life. Studies reporting long-term swallowing outcomes are lacking in the literature, and objective measures of swallowing function remain underutilized and nonstandardized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The incidence of head and neck cancer has dramatically increased in the last two decades due to human papillomavirus (HPV)-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC), a group of cancers, which affects predominantly young males and females who are nonsmokers and nondrinkers [1, 2]. The current management options for oropharyngeal cancer include either surgery upfront or “organ-preservation” chemo-radiation [3,4,5]. However, regardless of the treatment strategy used, both short-term and long-term negative effects on swallowing exist [3, 4, 6]. In fact, 80% of the patients treated for OPSCC will have swallowing dysfunction in daily life [7], with significant impacts on quality of life [8].

There are significant challenges in assessing and reporting dysphagia in this population, . Numerous generic and disease-specific quality-of-life instruments and patient-reported outcome questionnaires are available in the literature to assess subjective swallowing dysfunction in patients [8]. Objective measures of swallowing, including “gold-standard” modified barium swallow (MBS), often do not correlate well with patient’s symptoms and patient-reported outcome measures [9,10,11]. While the United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines recommend pretreatment assessment of speech and swallowing [5], no guidelines exist regarding routine measurement and reporting of swallowing outcomes post treatment for the head and neck cancer population. Nevertheless, it is increasingly recognized that functional outcomes, including swallowing function, are key treatment-related outcome measures that matter to patients and clinicians [3, 5, 12].

The primary aim of this study is to examine trends in the reporting of swallowing outcomes in clinical oropharyngeal cancer studies conducted during the last two decades. Our hypothesis is that swallowing outcomes are inconsistently reported with a large variety of measures employed.

Methods

Literature Search

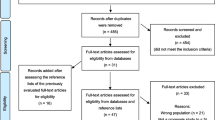

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines were employed and followed for conducting and reporting this review [13]. A systematic search of the literature was conducted by searching PubMed/MEDLINE (1966–2016) and Scopus (1988–2016) using the strategies outlined in Table 1. These are two of the largest electronic medical databases containing citations for biomedical and health sciences literature. Specifically, PubMed/MEDLINE has been shown to yield 80% of studies included in most systematic reviews [14]. Scopus is a multidisciplinary, generic database that provides overlapping coverage of databases including EMBASE and Compendex, but also includes publications in nonmedical disciplines [15].

Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria included (1) prospective and retrospective clinical studies involving adult patients with oropharyngeal cancer, (2)reports swallowing outcomes, (3) English studies or studies with English translation, (4) full text available for retrieval, and (5) publications between 1990 and 2016. The year 1990 was chosen to provide a sufficiently long period of observation to assess changes or trends in reporting of our outcomes of interest. Exclusion criteria were (1) narrative and literature review articles and case reports, (2) research in progress or gray literature, (3) insufficient information to extract data, and (4) the absence of reported swallowing outcomes.

Data Extraction and Assessment of Study Quality

In addition to application of strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, the quality of studies were further assessed by grading their levels of evidence based on the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Levels of Evidence for Therapy Studies [16]. Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts in duplicate. The full texts of the selected articles were then reviewed in full to extract relevant data. A third author resolved discrepancies. For each selected study, we identified the discipline of the primary or senior author (i.e., radiation oncology, surgical oncology, versus rehabilitation medicine) to determine if this impacts the rate of reporting of swallowing outcomes.

In studies reporting swallowing outcome measure, the specific measures used were also recorded and analyzed. The outcome measures were categorized as subjective if they were either clinician-reported or patient-reported outcome measures. Objective outcome measures included measures of swallowing dysfunction based on findings on MBS, flexible endoscopy evaluation of swallowing (FEES), and gastrostomy-tube (G-tube) status. Frequency statistics and descriptive statistics were performed using SPSS Version 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill., USA). Comparison of the rates of reporting of various outcome measures by the primary author's discipline was performed using Fischer Exact test with alpha significance of p < 0.05.

Results

After removing duplicates, 410 unique studies were identified that were appropriate for further review (Fig. 1). After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria and full manuscript review, we ultimately analyzed 106 studies that reported swallowing outcomes or measures of adult patients treated for oropharyngeal cancer. While the publication dates of the studies analyzed ranged from 1990 to 2016, the majority (> 78%) of studies reporting swallowing outcomes were published after 2010 (Fig. 2) demonstrating a more recent focus and recognition of dysphagia as an important outcome measure.

Of the studies analyzed, 75.4% of studies reported subjective swallowing outcomes (e.g., patient-reported or clinician-reported outcome measures), but only 30.2% of studies reported instrumental or objective measures of swallowing (Table 2). Many different subjective tools were used in the literature during the time period examined (Fig. 3). The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) Grade [17] was the most common tool used. MD Anderson Dysphagia Index [18] and University of Washington Quality of Life [19] were the most commonly used head and neck cancer-specific patient-reported outcome measurement tools used for assessing dysphagia outcomes.

Frequency of utilization of specific clinician- or patient-reported outcome measures .MDASI-HN MD Anderson Symptom Index Head & Neck, DOSS Dysphagia Outcome and Severity Scale, SWAL-QOL dysphagia-specific questionnaire, HNQOL Head and Neck Quality of Life Instrument, EORTC European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Head & Neck Module, UofWQOL-Sw University of Washing Quality of Life Swallowing Subdomain, MDADI MD Anderson Dysphagia Index, RTOG Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Dysphagia Grading

Most studies (61%) examined swallowing outcomes at one year or less from treatment, and 10% of studies examined 5-year outcomes. Only one study reported late swallowing dysfunction in patients more than 10 years from treatment initiation [20].

The primary authors were most commonly from the field of surgical oncology (64.6%), followed by medical and radiation oncology (17.4%), and speech-language pathology (12.7%). The proportion of studies that reported subjective outcomes, objective outcomes, or G-tube status varied depending on the specialty of the authors (Table 2). Studies with primary authors who were surgical oncologists had the highest rate of reporting subjective dysphagia outcomes (Table 2). Publications authored by first authors of speech-language pathology were more likely to report objective outcomes, and this was statistically significant when compared to those reported by other disciplines (Table 2). In studies that reported MBS results, the types of parameters reported were varied and included transit times, pharyngeal constriction, pharyngeal clearance, and the number of penetration or aspiration events. Six studies used at least one MBS scoring scale including the Swallowing Performance Scale [21,22,23,24,25], MBSImp [22], and the National Institute of Health-Swallowing Safety Scale (NIH-SSS) [24].

Discussion

As oropharyngeal cancers continue to increase in incidence in many countries around the world [1,2,3], long-term swallowing function of survivors is becoming an important consideration in clinical management. Objective or instrumental measures of swallowing are crucial components of evaluation of swallowing physiology and targeting therapy [9, 12, 21]. Consistent with our hypothesis, these measures are underutilized in the oropharyngeal cancer literature as only 30.2% of studies in our study reported results of FEES or MBS. Our review also found that studies involving speech language pathologists as primary authors were more likely to report objective measures of swallowing function.

On the other hand, subjective measures of swallowing, which include patient-reported outcomes, clinical assessments, and quality-of-life measures, are the most commonly reported dysphagia outcome measures used in the literature. Unfortunately, while subjective measures are convenient and can be more patient-centered, they can be nonspecific and often the choice of which tool to use is arbitrary. In addition, studies have shown that subjective measures of swallowing in head and neck cancer patients may not correlate with objective measures of swallowing physiology [10,11,12].

Our study also highlights the paucity of long-term data regarding swallowing function in oropharyngeal cancer patients. As long-term survival continues to improve in this population, late-treatment effects and their impacts on swallowing function are also increasingly recognized [3, 4, 26]. Furthermore, swallowing function is an important priority for patients when considering their treatment options [27]. Increasingly, swallowing outcomes are recognized as potential quality indicators that should be reported in surgical and nonsurgical trials involving oropharyngeal cancer patients [28, 29]. The exact tool or modality of assessing swallowing function that should be used remains debated.

There are several limitations to this study. We included only studies from the English language or with English translation available, which can skew our results toward institutions with similar approaches to reporting functional outcomes in oropharyngeal cancer patients. By including retrospective studies, prospective cohort studies, and also nonrandomized trials, it is not surprising that many studies do not report swallowing outcomes due to less-strict study design compared to randomized controlled trials. We also acknowledge that using the primary author’s discipline to make inferences about the overall perspective of studies is inexact, especially in the era of multidisciplinary research teams. Finally, a meta-analysis was not performed, and thus, formal assessment of heterogeneity could not be performed.

Conclusion and Recommendation for Future Research

As the number of oropharyngeal cancer survivors increase and treatment paradigms change, consistency in the literature regarding treatment outcome measures becomes increasingly important. International multidisciplinary focus groups may be needed in the development of guidelines for the reporting of swallowing outcomes in the oropharyngeal cancer population.

References

Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. Worldwide trends in incidence rates for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(36):4550–9.

Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(32):4294–301.

Goldsmith TA, Roe JW. Human papilloma virus-related oropharyngeal cancer: opportunities and challenges in dysphagia management. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;23:185–90.

Wall LR, Ward EC, Cartmill B, Hill AJ. Physiological changes to the swallowing mechanism following (chemo)radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Dysphagia. 2013;28:481–93.

Clarke P, Radford K, Coffey M, Stewart M. Speech and swallow rehabilitation in head and neck cancer: United kingdom national multidisciplinary guidelines. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130:S176–80.

Denaro N, Merlano MC, Russi EG. Dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients: pretreatment evaluation, predictive factors, and assessment during radio-chemotherapy recommendations. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;6(3):117–26.

Dwivedi RC, Chisholm EJ, Khan AS, et al. An exploratory study of the influence of clinico-demographic variables on swallowing and swallowing-related quality of life in a cohort of oral and oropharyngeal cancer patients treated with primary surgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269(4):1233–9.

Krekeler BN, Broadfoot CK, Johnson S, et al. Patient adherence to dysphagia recommendations: a systematic review. Dysphagia. 2018;33(2):173–84.

Jaffer NM, Ng E, Au FW, Steele CM. Fluoroscopic evaluation of oropharyngeal dysphagia: anatomic, technical, and common etiologic factors. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204(1):49–58.

Jensen K, Lambertsen K, Torkov P, et al. Patient assessed symptoms are poor predictors of objective findings Results from a cross sectional study in patients treated with radiotherapy for pharyngeal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2007;46(8):1159–68.

Kendall KA, Tanner K, Kosek SR. Quality-of-life scores compared to objective measures of swallowing after oropharyngeal chemoradiation. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(3):682–7.

Lazarus CL. Effects of chemoradiotherapy on voice and swallowing. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;17(3):172–8.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. Methods of systematic reviews and meta-analysis: the PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–34.

Booth A. How much searching is enough? Comprehensive versus optimal retrieval for technology assessments. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2012;26:431–5.

Burnham JF. Scopus database: a review. Biomed Digit Libr. 2006;3:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-5581-3-1.

Phillips Bob, Ball Chris, Sackett Dave, et al. Oxford Centre for evidence-based medicine–levels of evidence. CEBM: University of Oxford; 2009.

Cox JD, Stetz J, Pajak TF. Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31(5):1341–6.

Hassan SJ, Weymuller EA. Assessment of quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. Head Neck. 1993;15(6):485–96.

Chen AY, Frankowski R, Bishop-Leone J, et al. The development and validation of a dysphagia-specific quality-of-life questionnaire for patients with head and neck cancer: the M.D. Anderson dysphagia inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127(7):870–6.

Hutcheson KA, Yuk MM, Holsinger FC, et al. Late radiation-associated dysphagia with lower cranial neuropathy in long-term oropharyngeal cancer survivors: video case reports. Head Neck. 2015;37(4):E56–62.

Eisbruch A, Kim HM, Feng FY, et al. Chemo-IMRT of oropharyngeal cancer aiming to reduce dysphagia: swallowing organs late complication probabilities and dosimetric correlates. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(3):e93–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.12.067Epub 2011 May 17.

Hutcheson KA, Lewin JS, Barringer DA, et al. Late dysphagia after radiotherapy-based treatment of head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2012;118(23):5793–9. .

Nguyen NP, Frank C, Moltz CC, et al. Analysis of factors influencing aspiration risk following chemoradiation for oropharyngeal cancer. Br J Radiol. 2009;82(980):675–80.

Eisbruch A, Kim HM, Feng FY, et al. Chemo-IMRT of oropharyngeal cancer aiming to reduce dysphagia: swallowing organs late complication probabilities and dosimetric correlates. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(3):e93–9.

Nguyen NP, Frank C, Moltz CC, et al. Dysphagia severity and aspiration following postoperative radiation for locally advanced oropharyngeal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2008;28(1B):431–4.

Hutcheson KA, Yuk M, Hubbard R, et al. Delayed lower cranial neuropathy after oropharyngeal intensity-modulated radiotherapy: a cohort analysis and literature review. Head Neck. 2017;39(8):1516–23.

Wilson JA, Carding PN, Patterson JM. Dysphagia after nonsurgical head and neck cancer treatment: patients’ perspectives. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145(5):767–71.

Simon C, Caballero C, Gregoire V, et al. Surgical quality assurance in head and neck cancer trials: an EORTC Head and Neck Cancer Group position paper based on the EORTC 1420 ‘Best of’ and 24954 ‘larynx preservation’ study. Eur J Cancer. 2018;103:69–77.

Simon C, Caballero C. Quality assurance and improvement in head and neck cancer surgery: from clinical trials to National Healthcare Initiatives. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2018;19(7):34.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, P., Constantinescu, G.C., Nguyen, NT.A. et al. Trends in Reporting of Swallowing Outcomes in Oropharyngeal Cancer Studies: A Systematic Review. Dysphagia 35, 18–23 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-019-09996-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-019-09996-7