Abstract

Following cardiovascular (CV) surgery, prolonged mechanical ventilation of >48 h increases dysphagia frequency over tenfold: 51 % compared to 3–4 % across all durations. Our primary objective was to identify dysphagia frequency following CV surgery with respect to intubation duration. Our secondary objective was to explore characteristics associated with dysphagia across the entire sample. Using a retrospective design, we stratified all consecutive patients who underwent CV surgery in 2009 at our institution into intubation duration groups defined a priori: I (≤12 h), II (>12 to ≤24 h), III (>24 to ≤48 h), and IV (>48 h). Eligible patients were >18 years old who survived extubation following coronary artery bypass alone or cardiac valve surgery. Patients who underwent tracheotomy were excluded. Pre-, peri-, and postoperative patient variables were extracted from a pre-existing database and medical charts by two blinded reviewers. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Across the entire sample, multivariable logistic regression analysis determined independent predictors of dysphagia. Across the entire sample, dysphagia frequency was 5.6 % (51/909) but varied by group: I, 1 % (7/699); II, 8.2 % (11/134); III, 16.7 % (6/36); and IV, 67.5 % (27/40). Across the entire sample, the independent predictors of dysphagia included intubation duration in 12-h increments (p < 0.001; odds ratio [OR] 1.93, 95 % confidence interval [CI] 1.63–2.29) and age in 10-year increments (p = 0.004; OR 2.12, 95 % CI 1.27–3.52). Patients had a twofold increase in their odds of developing dysphagia for every additional 12 h with endotracheal intubation and for every additional decade in age. These patients should undergo post-extubation swallow assessments to minimize complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dysphagia is a recognized complication following extubation that can lead to increased morbidity, mortality [1], and hospital costs [2]. While a patient’s dysphagia risk increases following prolonged periods of mechanical ventilation, no study to date has reported dysphagia frequencies across stratified intubation durations following both coronary artery bypass grafting and cardiac valve surgery [3]. All patients undergoing cardiovascular (CV) surgery require endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation as part of standard surgical intervention; however, the duration of intubation after surgery varies [4, 5]. When intubation exceeds 48 h following CV surgery, the frequency of swallowing impairments (dysphagia) is 51 % [6], approximately ten times greater than that of the CV surgical population as a whole [2, 7, 8].

The number of studies that focus on dysphagia following CV surgery are few [2, 6–12], and the evidence surrounding the relationship between intubation duration and dysphagia in this population is limited [3]. In particular, most studies addressing intubation duration report cumulative dysphagia frequencies regardless of intubation periods [2, 7, 8], with only two studies focusing on specific intubation durations: >48 h [6] and from 8 to 28 h [9]. As a result, dysphagia frequencies following intubation of <24 h or between 24 and 48 h have yet to be reported. In addition to the limitations in the CV surgery literature, discrepancies also exist regarding the definition of prolonged intubation in other diagnostic groups [13–16]. In those studies prolonged intubation is defined as >24 h [13], >48 h [14, 15] or as long as 8 days [16]. Overall, dysphagia following extubation regardless of the diagnostic group requires further investigation [3].

Our primary goal was to report the frequency of dysphagia according to varying intubation duration following coronary artery bypass grafting and/or cardiac valve surgery. Furthermore, we also sought to explore the characteristics associated with dysphagia across this CV surgical population thereby determining those at greatest risk for dysphagia.

Patients and Methods

Following institutional ethics board approval, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of all consecutive patients who underwent CV surgery in a 12-month period (January–December 2009) at a single institution. We included adult patients (>18 years of age) who survived their final extubation following coronary artery bypass alone or valve replacements and/or repairs as their primary procedure. We excluded patients who underwent cardiac transplantation, implantation of ventricular assist devices, repair of adult congenital heart defects, and other complex procedures. Patients who underwent a pre- or postoperative tracheotomy were also excluded.

Data Abstraction

Demographic, clinical, and operative patient data from electronic medical charts and the existing CV surgery database were utilized for this study.

The electronic chart review was conducted in accordance with a data abstraction manual that we developed and finalized a priori. Two raters (SAS and a research assistant), blinded to each other, reviewed the electronic charts of all patients who met the study’s inclusion criteria. The reviewers recorded data regarding (1) extubation dates and times, (2) perioperative transesophageal echocardiography, and (3) medical orders and nursing staff documentation pertaining to tube feeding, assessment by speech-language pathology (SLP), and dietary texture modifications. Data were recorded using a pre-established form. Disagreements between raters were resolved by consensus.

The CV Surgery database is completed prospectively for all patients who undergo CV surgery at our institution [17]. Trained CV surgery research nurses collect and enter the data. Their reliability is regularly monitored through internal chart audits. Only the variables of interest were extracted from this database for this study, including those pertaining to demographics as well as preoperative, perioperative, and postoperative outcomes.

Operational Definitions

Both intubation duration strata and oropharyngeal dysphagia were defined a priori. Specifically, intubation durations were grouped into four strata: I (≤12 h), II (>12 to ≤24 h), III (>24 to ≤48 h), and IV (>48 h). Dysphagia was defined as any abnormality of the oral, pharyngeal, or upper esophageal stage of deglutition resulting in impairment in swallowing. Impairment was identified by any one of the following medical orders that occurred within 96 h following the patient’s final extubation: (1) enteral feeding, (2) swallowing assessment order recommending enteral feeding, modified-texture diet, or nil per os (NPO), or (3) modified-texture diet order written by a speech-language pathologist or medical staff.

Statistical Analyses

We report data as frequency, mean with standard deviation (SD), and median with interquartile range (IQR) as appropriate. The frequency of dysphagia was summarized descriptively. Comparisons were made between those with and those without dysphagia across the entire study sample, using Mann–Whitney or unpaired 2-sided t-tests for continuous variables and Pearson’s χ 2 test or Fisher’s exact test for proportions. Missing variables were imputed with the median. Variables for our main-effect regression model were selected using a backward stepwise bootstrapping method (n = 1,000, inclusion threshold p < 0.05). In order to avoid colinearity, predictor variables that were deemed clinically redundant were not entered into the bootstrap. We considered variables occurring in >10 % of the bootstrapping resamples for our final model. Our final regression was conducted using a backward stepwise method. For the purposes of the bootstrap and regression, the following variables were dichotomized and/or defined as: (1) moderate left ventricular (LVEF <40 %) dysfunction, (2) New York Heart Association (NYHA) class IV symptoms, (3) myocardial infarction within 30 days preoperatively, and (4) a nonelective surgical procedure.

Bivariate analyses were conducted using IBM® SPSS© v19.0 for Mac OS X (IBM®, Armonk, NY, USA). Bootstrap and regression modeling were conducted using SAS v9.1 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). We determined statistical significance by a 2-tailed p < 0.05.

Results

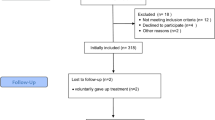

A total of 1,480 patients underwent CV surgery between January 1 and December 31, 2009, at our institution. Of those, 944 patients underwent coronary artery bypass grafting or valve repairs and/or replacements as their primary procedure. Of the 944 patients, a total of 35 patients were excluded: 17 patients died while intubated, 17 underwent a tracheotomy, and one patient had no recorded intubation time. The remaining 909 patients were then stratified according to intubation duration: I (≤12 h) included 699 patients (76.9 % of total), II (>12 to ≤24 h) 134 patients (14.7 % of total), III (>24 to ≤48 h) 36 patients (4.0 % of total), and IV (>48 h) 40 patients (4.4 % of total).

Dysphagia Frequency and Criteria

Dysphagia frequency was 5.6 % (51/909) across the entire study sample but varied across intubation groups: I, 1.0 % (7/699); II, 8.2 % (11/134); III, 16.7 % (6/36); and IV, 67.5 % (27/40) (Table 1). Of the 51 patients with dysphagia, 47 (92 %) met two or more of our criteria for dysphagia, with nearly half (25/51, 49 %) meeting all three. Four patients (8 %) met only one of our dysphagia criteria. All four of these patients required enteral feeding as their primary form of nutrition and had a Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of 14 or higher. The first dysphagia criterion was met within 24 h following extubation by 19 patients (37 %), within 48 h by 18 patients (35 %), within 72 h by 9 patients (18 %), and within 96 h by 5 (10 %) patients.

Intubation Duration Across Study Sample

Median intubation duration [IQR] for all patients was 6.9 h [6.2]. Across the entire sample, those with dysphagia had a significantly longer median intubation duration than those without (68.8 h [93.7] vs. 6.8 h [5.2]; p < .001).

Patient Characteristics Across Study Sample

Demographic variables and preoperative clinical characteristics are presented in Table 2. Across the sample, the mean (±SD) age was 65.9 years (±12.0). Those with postoperative dysphagia were significantly older than those without (74.3 ± 8.7 vs. 65.4 ± 12.0 years; p < 0.001), with proportionately more having at least moderate chronic kidney disease (58.8 vs. 19.9 %; p < 0.001). Cardiovascular surgical risk factors differed between those with and those without dysphagia, including NYHA symptom class (p = 0.008), congestive heart failure (41.2 vs. 16.9 %, p < 0.001), preoperative atrial fibrillation (17.6 vs. 5.6 %, p = 0.003), and preoperative stroke or transient ischemic attack (25.5 vs. 8.7 %, p = 0.001). Some patient characteristics were not discriminatory, including diabetes, preoperative myocardial infarction, hypertension, and respiratory risks such as a history of smoking. Of the entire study sample (n = 909), there was missing data from 1 to 11 patients (0.1–1.2 %) for the following variables: family history of heart disease (1.0 %), diabetes (0.1 %), LV grade (0.4 %), NYHA symptom class (1.2 %), hyperlipidemia (0.2 %), smoking history (0.2 %) and chronic kidney disease (0.1 %) (Table 2).

Of 909 patients, 567 (62.4 %) underwent coronary artery bypass as their primary surgery, with the remaining patients (342/909, 37.6 %) undergoing valve repair and/or replacement. Many operative characteristics and perioperative complications distinguished those with and without dysphagia (Table 3). More patients with dysphagia underwent valve repair and/or replacement than coronary artery bypass grafting (60.8 vs. 39.2 %, p = 0.001) and also required a perioperative transesophageal echocardiogram (74.5 vs. 44.3 %, p < 0.001). Patients with dysphagia also had more perioperative strokes, sepsis, and low output syndrome. Lastly, more patients with dysphagia required intra-aortic balloon pump placement (15.7 vs. 2.9 %, p < 0.001) and/or inotropic support (54.9 vs. 39.5 %, p = 0.039) than patients without.

Postoperative outcomes also differed between those with and without dysphagia (Table 4). In addition to longer intubation durations, those with dysphagia had significantly higher rates of reintubation (p < 0.001), reoperation (p < 0.001), and postoperative atrial fibrillation (p = 0.002). While patients with dysphagia had longer stays in the intensive care unit (p < 0.001), they were not readmitted to the intensive care unit at a greater rate (p = 0.108).

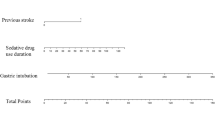

After exclusion of clinically redundant predictor variables, 26 variables were entered into the bootstrapping selection model. Of those, 13 were included in >10 % of the bootstrap resamples and were subsequently entered into the multivariate model (Table 5). Findings from logistic regression analysis identified the following independent predictors of dysphagia: intubation duration (p < 0.001; OR 1.93, 95 % CI 1.63–2.29) for every 12-h increment, age (p = 0.004; OR 2.12, 95 % CI 1.27–3.52) for every 10-year increment, and the occurrence of postoperative sepsis (p = 0.01; OR 14.03, 95 % CI 1.78–110.72) with a model c-statistic of 0.94.

Discussion

This study is the first to report dysphagia frequency across stratified intubation durations after both coronary artery bypass and cardiac valve surgery. We determined that dysphagia frequency (1) is highest following intubation exceeding 48 h, (2) is negligible in those patients intubated for ≤12 h, and (3) exceeds the cumulative population incidence previously reported [2, 7, 8] in those intubated between 12 and 48 h. Most notably, our findings are the first to determine that the odds of a patient having dysphagia increase by a factor of 2 for every additional 12 h of endotracheal intubation or for every additional decade of age.

Similar to previous work, this study identified many pre- and perioperative risk factors associated with dysphagia as well as three independent predictors: advanced age [7], prolonged intubation [6, 7], and sepsis [6]. While we also found that both pre- and perioperative stroke [6, 8] as well as TEE use [7, 8] were more common in those presenting with dysphagia, neither variable proved to be independently predictive of dysphagia in our study. Although TEE use was not predictive of dysphagia in our study, the frequency of dysphagia was more common in those patients who underwent valve surgery than in those who underwent bypass. While some studies have reported higher gastrointestinal complications, including gastrointestinal ischemia and hemorrhage, following valve surgery [18, 19], to our knowledge no study has compared the occurrence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in those who underwent bypass versus valve surgery. Although comparing the frequency of dysphagia between these two patient groups (valve vs. bypass) was outside the scope of the current study, we feel that it does warrant investigation in the future. While only speculative, this difference is likely multifactorial and may be related to the type of surgery or any number of other factors such as baseline cardiac function, pre-existing medical comorbidities, perioperative stroke, cardiopulmonary bypass time, inotropic support, or intubation duration.

The frequency of dysphagia across our entire sample is similar to that reported previously [2, 7, 8]. Specifically, our results also confirm previously reported low frequencies for patients intubated ≤12 h [9]. In addition, we confirmed that those patients intubated for >48 h were at the greatest risk of developing dysphagia; our dysphagia frequency for that intubation group was 67.5 %, a much higher frequency than previously reported [6]. Although the study by Barker and colleagues [6] was conducted at the same institution, patients in our study who had intubation >48 h were older and had a higher NYHA symptom class, suggesting a population at increased risk of complications.

Establishing the cause of dysphagia following endotracheal intubation is a challenge often because of patients’ medical complexity and comorbidities. While determining causation is outside the scope of the current study, some have reported structural and mechanical alterations to the upper airway following extubation in those patients with dysphagia [16, 20]. In addition, various intubation techniques and induction medication can either positively or negatively affect protective airway reflexes [21].

Our study had limitations that were inherent in its retrospective nature. We were unable to investigate baseline swallowing status as well as rule out all pre-existing medical conditions that may predispose a patient to dysphagia such as neurological disorders [22]. Our postoperative definition of dysphagia was also limited to bedside speech-language pathology assessment findings as well as surrogate nutrition variables such as a modified-texture diet or tube feeding as few patients received instrumental swallowing assessments. However, our identification of those with dysphagia was conservative. Specifically, we limited initial identification of dysphagia to within 96 h of final extubation, and most patients met multiple criteria for the presence of dysphagia. The dysphagic patients had adequate consciousness as assessed by the GCS scores and/or nursing records. We were unable to fully assess the presence of delirium as formal delirium screening scores were not recorded and they could not be derived from the available data. Finally, our data were limited to a single large, quaternary-care cardiac center serving a broad multiethnic demographic, suggesting but not proving that our findings would be applicable to similar centers. Limitations notwithstanding, we attempted to maintain methodological rigor, maximize generalizability, and minimize bias in several ways: (1) developing a priori operational definitions of dysphagia and our descriptive intubation strata, (2) including a homogeneous patient sample typical of many CV surgery centers, and (3) maintaining blinding throughout our data collection.

In conclusion, our description of dysphagia frequency, according to varying intubation durations in a CV surgery population, demonstrated that the highest risk of dysphagia occurs in patients intubated for more than 48 h. We identified risk factors associated with dysphagia as well as its independent predictors across the entire study sample. In general, older patients, those with perioperative sepsis, and longer intubation had the greater risk for dysphagia. While further prospective studies are needed to determine perioperative or comorbid factors that affect dysphagia severity and/or recovery, the present findings will serve as an important first step in the identification of at-risk patients following extubation.

References

Macht M, Wimbish T, Clark BJ, et al. Postextubation dysphagia is persistent and associated with poor outcomes in survivors of critical illness. Crit Care. 2011;15:R231.

Ferraris VA, Ferraris SP, Moritz DM, Welch S. Oropharyngeal dysphagia after cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:1792–5.

Skoretz SA, Flowers HL, Martino R. The incidence of dysphagia following endotracheal intubation: a systematic review. Chest. 2010;137:665–73.

Reddy SL, Grayson AD, Griffiths EM, Pulan DM, Rashid A. Logistic risk model for prolonged ventilation after adult cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:528–36.

Cislaghi F, Condemi AM, Corona A. Predictors of prolonged mechanical ventilation in a cohort of 5123 cardiac surgical patients. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009;26:396–403.

Barker J, Martino R, Reichardt B, Hickey EJ, Ralph-Edwards A. Incidence and impact of dysphagia in patients receiving prolonged endotracheal intubation after cardiac surgery. Can J Surg. 2009;52:119–24.

Hogue CW Jr, Lappas GD, Creswell LL, et al. Swallowing dysfunction after cardiac operations. Associated adverse outcomes and risk factors including intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110:517–22.

Rousou JA, Tighe DA, Garb JL, et al. Risk of dysphagia after transesophageal echocardiography during cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:486–90.

Burgess GE 3rd, Cooper JR Jr, Marino RJ, Peuler MJ, Warriner RA 3rd. Laryngeal competence after tracheal extubation. Anesthesiology. 1979;51:73–7.

Harrington OB, Duckworth JK, Starnes CL, et al. Silent aspiration after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:1599–603.

Partik BL, Scharitzer M, Schueller G, et al. Videofluoroscopy of swallowing abnormalities in 22 symptomatic patients after cardiovascular surgery. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:987–92.

Messina AG, Paranicas M, Fiamengo S, et al. Risk of dysphagia after transesophageal echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 1991;67:313–4.

de Larminat V, Montravers P, Dureuil B, Desmonts JM. Alteration in swallowing reflex after extubation in intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:486–90.

Ajemian MS, Nirmul GB, Anderson MT, Zirlen DM, Kwasnik EM. Routine fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing following prolonged intubation: implications for management. Arch Surg. 2001;136:434–7.

Leder SB, Cohn SM, Moller BA. Fiberoptic endoscopic documentation of the high incidence of aspiration following extubation in critically ill trauma patients. Dysphagia. 1998;13:208–12.

Tolep K, Getch CL, Criner GJ. Swallowing dysfunction in patients receiving prolonged mechanical ventilation. Chest. 1996;109:167–72.

Rao V, Ivanov J, Weisel RD, Ikonomidis JS, Christakis GT, David TE. Predictors of low cardiac output syndrome after coronary artery bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;112:38–51.

Bolcal C, Iyem H, Sargin M, et al. Gastrointestinal complications after cardiopulmonary bypass: sixteen years of experience. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19:613–7.

D’Ancona G, Baillot R, Poirier B, et al. Determinants of gastro-intestinal complications in cardiac surgery. Tex Heart Inst J. 2003;30:280–5.

Postma G, McGuirt WF Sr, Butler SG, Rees CJ, Crandall HL, Tansavatdi K. Laryngopharyngeal abnormalities in hospitalized patients with dysphagia. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:1720–2.

Mencke T, Echternach M, Kleinschmidt S, et al. Laryngeal morbidity and quality of tracheal intubation: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1049–56.

Martino R, Foley N, Bhogal S, Diamant N, Speechley M, Teasell R. Dysphagia after stroke: incidence, diagnosis, and pulmonary complications. Stroke. 2005;36:2756–63.

Acknowledgments

SAS was supported by an Ontario Graduate Scholarship from the Ontario Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities. TMY holds the Angelo & Lorenza DeGasperis Chair in Cardiovascular Surgery Research. JI is a staff scientist supported by the Division of Cardiology with the University Health Network and Mount Sinai Hospital. JTG is a physician with the Division of Respirology and Interdepartmental Division of Critical Care with the University Health Network. RM is supported by a Career Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research in Aging. SAS, TMY, JI, JTG, and RM had full control of the design of the study, methods, used, outcome parameters and results, analysis of data and production of the written report. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of: Samir Basmaji for data abstraction and Katie Vikken for data entry.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Skoretz, S.A., Yau, T.M., Ivanov, J. et al. Dysphagia and Associated Risk Factors Following Extubation in Cardiovascular Surgical Patients. Dysphagia 29, 647–654 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-014-9555-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-014-9555-4