Abstract

Despite the wide implementation of dysphagia therapies, it is unclear whether these therapies are successfully communicated beyond the inpatient setting. The aim of this study was to examine the rate of dysphagia recommendation omissions in hospital discharge summaries for high-risk subacute care (i.e., skilled nursing facility, rehabilitation, long-term care) populations. We performed a retrospective cohort study that included all stroke and hip fracture patients billed for inpatient dysphagia evaluations by speech-language pathologists (SLPs) and discharged to subacute care from 2003 through 2005 from a single large academic medical center (N = 187). Dysphagia recommendations from final SLP hospital notes and from hospital (physician) discharge summaries were abstracted, coded, and compared for each patient. Recommendation categories included dietary (food and liquid), postural/compensatory techniques (e.g., chin tuck), rehabilitation (e.g., exercise), meal pacing (e.g., small bites), medication delivery (e.g., crush pills), and provider/supervision (e.g., 1-to-1 assist). Forty-five percent of discharge summaries omitted all SLP dysphagia recommendations. Forty-seven percent (88/186) of patients with SLP dietary recommendations, 82% (93/114) with postural, 100% (16/16) with rehabilitation, 90% (69/77) with meal pacing, 95% (21/22) with medication, and 79% (96/122) with provider/supervision recommendations had these recommendations completely omitted from their discharge summaries. Discharge summaries omitted all categories of SLP recommendations at notably high rates. Improved post-hospital communication strategies are needed for discharges to subacute care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dysphagia is a serious yet common problem in older adults, especially for those in hospital settings and in subacute care facilities (i.e., skilled nursing, rehabilitation, and long-term care facilities) [1–3]. Patients with stroke or hip fracture, the most common reasons for subacute care admission [4, 5], are at especially high dysphagia risk. From 40 to 70% of older adults with acute stroke experience dysphagia [6–9]. Moreover, hip fracture patients discharged to subacute care have high rates of coexisting dementia [10–12], which places them at significantly increased dysphagia risk [13–16]. Dysphagia leads to a myriad of complications, including malnutrition, dehydration, and pneumonia, costing more than $4.4 billion annually [17, 18]. It is often diagnosed within the hospital setting by speech-language pathologists (SLP), who assess swallowing ability and make effective dietary, behavioral, and provider recommendations to decrease the risk of dysphagia-related complications [19–25]. However, hospital-based physicians and SLPs rarely accompany patients to the post-hospital care setting [26], and post-hospital communication of patient care plans is often problematic [26–30]. Poor discharge communication could lead to inappropriate post-hospital dysphagia care, with resultant aspiration pneumonia and need for costly rehospitalization.

The hospital discharge summary is the only document mandated by The Joint Commission to convey the patient’s care plan to the post-hospital setting [31]. Although hospitals often utilize additional discharge paperwork, these other documents are institution-specific, not required, and not always present [27, 32–35]. Direct verbal communication between care settings is rare [27]. Despite the critical communication role discharge summaries play, they are not standardized and often lack important components that experts recognize as crucial to ensuring patient safety [27, 28, 30, 36]. It remains unknown how well discharge summaries communicate SLP dysphagia recommendations to post-hospital settings.

To enhance the design of transitional care programs that improve between-facility communication, we examined the rate of SLP dysphagia recommendation omissions in hospital discharge summaries for stroke and hip fracture patients transitioning from hospital to subacute care facilities.

Methods

Study Sample

We identified all hospitalized patients 18 years and older with primary diagnoses of stroke or pelvis/hip/femur fracture who received a billed inpatient SLP dysphagia evaluation and who were discharged to subacute care facilities during the period 2003–2005 from a single large academic medical center. We established primary diagnoses using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD-9) diagnosis code in the first position on the acute hospitalization discharge diagnosis list. ICD-9 codes of 431, 432, 434, and 436 were used to identify stroke [37–39], and 805.6, 805.7, 806.6, 806.7, 808, and 820 were used to identify pelvis/hip/femur fracture (hereafter simply “hip fracture”) [40–42]. We identified discharges to subacute care facilities through the use of administrative data compiled on a mandatory basis for all study hospital patients by hospital case managers. Internal testing of these data by the study hospital noted greater than 95% reliability of this discharge field. We identified patients with inpatient SLP evaluations (either bedside or instrumental) by examining hospital billing records for Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes of 92610 (“evaluation of oral and pharyngeal swallowing function”), 92611 (“motion fluoroscopic evaluation of swallowing”), and 92612 (“flexible fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing”) billed out of the study hospital’s swallowing service. The initial sample size was 218 prior to exclusions.

SLP hospital chart notes for each patient were located within the combination paper/electronic patient hospital chart for the eligible hospitalization. Discharge summaries for all eligible patients were obtained electronically from the study hospital. Patients were excluded if they did not have a discharge summary (N = 2), did not have dysphagia recommendations listed in their SLP hospital chart notes (N = 10), were discharged to hospice or comfort care (N = 1), if it was clear from their discharge summary that they did not have a diagnosis of stroke or hip fracture (N = 12), or were not discharged to a subacute care facility (N = 6), for a final sample size of 187. No patient was included more than once in the sample. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the participating university approved this study with a waiver of consent.

Dysphagia Recommendation Categorization

We developed a coding scheme for all recommendations typically made by a SLP during the routine course of dysphagia evaluation and treatment. To accomplish this, we convened a consensus team of two SLPs, two physicians, and one medical student (the authors) to locate typical SLP recommendations via a review of the dysphagia literature [43–52] and to create a logical categorization of all recommendations found (N = 165). The team created seven major categories of dysphagia recommendations, including (1) Dietary Recommendations and Restrictions, (2) Postural and Compensatory Techniques, (3) Rehabilitative Techniques, (4) Pacing, Sizing, and Procedural Techniques, (5) Medications—Pill Recommendations, (6) Care Provider and Communication Recommendations, and (7) Environment/Other (Table 1). Large categories were divided into subcategories. For each specific recommendation within each category/subcategory, we applied a distinct 4-digit code that was used in the coding and analysis processes.

Abstraction and Coding Process

Final SLP Hospital Chart Note

Through a manual review of all documentation from each patient’s eligible hospitalization, the last SLP note containing recommendations prior to discharge (i.e., the “final SLP note”) was identified. Recommendations within this note were abstracted verbatim into electronic forms by a single medical abstractor (medical student) using a standardized abstraction protocol and manual. (Prior to formal chart abstraction activities, this abstractor underwent half a day of training on study protocol and abstraction approaches, including test abstractions and parallel abstractions with immediate feedback.) Each abstracted recommendation was then coded using the 4-digit codes developed above. To assess the reliability and validity of this process, a SLP who was originally involved in 5% of our sample’s care and who had performed and written the final SLP notes on these patients herself, performed retrospective reabstractions of her dysphagia recommendations within all of her own final notes. She was blinded to the original abstraction results. These reabstractions were coded and compared with the original abstractions. A total of 66 SLP dysphagia recommendations were compared, with a total agreement of 99% between the two abstractors (Cohen’s κ = 0.9).

Hospital Discharge Summary

Two trained medical abstractors (one nurse practitioner and one physician), using standardized abstraction protocols, forms, and manuals, reviewed all sample discharge summaries for the presence or absence of dysphagia recommendations/orders. All dysphagia recommendations within the discharge summaries were abstracted verbatim onto paper abstraction forms, entered into an electronic database, and manually coded. Ten percent of discharge summaries were reabstracted with a 92% interabstractor agreement noted for the presence/absence of dysphagia recommendations (Cohen’s κ = 0.7). The discharge summary abstraction team was fully blinded to all contents of the SLP hospital chart notes.

Analysis

We calculated the prevalence of dysphagia recommendations within final SLP hospital chart notes and discharge summaries. Next, for each patient, we compared the coded dysphagia recommendations obtained from the patient’s final SLP hospital chart note with those obtained from the patient’s discharge summary. Discharge summary omissions of specific SLP dysphagia recommendations were noted for each patient. Omission frequencies were calculated for each dysphagia recommendation category and subcategory. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 and STATA version 10.1 [53, 54].

Results

Patient and Discharge Summary Characteristics

Of the 187 eligible patients within this study, 159 (85%) had a primary diagnosis of stroke while 28 (15%) had a primary diagnosis of hip fracture. Discharge summaries averaged 3.6 pages (range = 2–9) and originated from a variety of hospital services, including neurosurgery, neurology, orthopedic surgery, and general internal medicine. Nearly all of the discharge summaries were dictated by a physician resident (e.g., medical resident, surgical resident, neurology resident), although 96% were ultimately reviewed, edited, and signed by the attending physician.

Prevalence of Dysphagia Recommendations

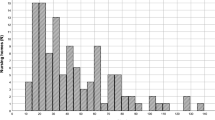

Final SLP hospital chart notes contained an average of 5.6 recommendations per note (range = 1–15), while patient discharge summaries contained an average of 1.4 recommendations per discharge summary (range = 0–9). Both SLP notes and discharge summaries included “dietary recommendations and restrictions” most often, with 99% of final SLP notes and 52% of discharge summaries including at least one recommendation within this category (Fig. 1). “Care provider and communication recommendations” were the next most often included, with 65% of SLP notes and 18% of discharge summaries including at least one recommendation within this category. “Postural and compensatory techniques” were the third most often included in both note types, followed by the categories of “pacing, sizing, and procedural techniques,” “medications—pill recommendations,” “rehabilitative techniques,” and “environment.” Prevalence of the most common specific recommendations within each category is demonstrated in Appendix Table 3. Overall, dysphagia recommendations were less often included within discharge summaries than within SLP notes, regardless of the category.

Omission of Dysphagia Recommendations Within Discharge Summaries

Table 2 demonstrates the frequencies at which patient discharge summaries omitted specific SLP dysphagia recommendations. Overall, 45% of patient discharge summaries omitted all of the dysphagia recommendations made within the final SLP hospital note, while 42% of discharge summaries omitted at least one (but not all) of the SLP recommendations (i.e., omitted some recommendations). Thirteen percent of patient discharge summaries included all of the SLP recommendations made (i.e., omitted no recommendations).

Forty-seven percent of patients with dietary recommendations and restrictions made by their SLP had these recommendations completely omitted from their discharge summary (Table 2). This category had the lowest omission rate of all categories studied. In this category, SLP tube-feeding recommendations were the least commonly omitted. All other types of SLP dietary recommendations were omitted at rates of 54% or greater. Recommendations for diets other than “general” accounted for approximately 60% of all omissions within the food recommendation category, while recommendations for liquid consistencies other than “thin” accounted for approximately 22% of all omissions within the liquid recommendation category (Appendix Table 3).

From 79 to 100% of patients with nondietary SLP recommendations had these other recommendations fully omitted from their discharge summaries (Table 2). The most numerous specific omissions in these nondietary categories included recommendations for elevating the head of the patient’s bed during or after meals, one-to-one supervision or feeding assistance during meals, eating slowly or with only small bites, performing a chin tuck during swallowing, crushing tablet medications, specific rehabilitative tongue/mouth exercises, and instructions for following up with the SLP for further evaluation (Appendix Table 3).

Rarely, discharge summaries included specific dysphagia recommendations not made within the SLP hospital chart note (Appendix Table 3). The most common of these recommendations were instructions for pureed or mechanical soft diets (20 discharge summaries) and for one-to-one feeding assistance (7 discharge summaries).

Discussion

In this study we found that inpatient SLP dysphagia therapy recommendations were frequently omitted from the discharge summaries of subacute care patients at high risk for aspiration pneumonia. Nondietary recommendations were omitted at the highest rates, in some categories nearing 80-100%, while dietary recommendations were omitted for nearly half of all patients. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine and report on deficiencies in dysphagia therapy communication at the time of hospital discharge.

The frequent omission of dysphagia recommendations in hospital discharge summaries may be attributable to a number of dictating provider (i.e., physician) and system factors. Despite the demonstrated effectiveness of dysphagia therapies in preventing aspiration and subsequent pneumonias [19, 20, 23–25], physicians may undervalue the importance of these therapies, preferentially focusing on physician-prescribed therapies (i.e., medications) for transmission within the discharge summary plan. The communication of dysphagia therapies may also be perceived by the dictating physician as a “nursing role,” one that is dealt with during the nursing hand-off (i.e., the telephone communication which typically occurs between the discharging hospital nurse and the receiving subacute care nurse at the time of the patient’s discharge from the hospital). However, nursing hand-offs do not result in written documentation as universally present or as widely disseminated as the discharge summary [27]. In addition, system factors, including poor in-hospital communication [55–57], large workloads [58, 59], and cumbersome discharge summary and medical record systems [60–63], likely contribute to dysphagia omissions.

This is not the first study to demonstrate omission of critical patient care plan components in hospital discharge summaries. Studies of discharge summaries in Britain and Canada have demonstrated frequent omissions of important details [27, 35, 36, 64–67]. A systematic review by Kripalani et al. [27] noted that discharge summaries frequently omit diagnostic test results, treatment courses, discharge medications, pending test results, and follow-up plans. However, there is a notable lack of attention to treatment plan components made by allied health providers in these studies, including dysphagia treatment recommendations made by hospital-based SLPs. As hospitalized older adults increasingly rely on multidisciplinary care teams and as research continues to highlight the critical impact transitional care quality has on patient safety in the early post-discharge period [68–71], it becomes clear that a shift in the physician-centered approach to discharge summary documentation may be needed.

Although patient outcomes were not studied within this particular analysis, the potential impact that dysphagia omissions may have on patient health is concerning. The evidence-based dysphagia therapy recommendations made by inpatient SLPs have been shown to decrease adverse patient events [19, 20, 23–25]. However, if these therapies are not communicated to or continued within the post-hospital care setting, any benefits they may have conveyed could be lost. As such, omission of food and body-positioning recommendations within discharge summaries may lead to inappropriate or unsafe patient care, thus increasing the risk of aspiration and subsequent pneumonia within the subacute care facility. This is an important linkage because accreditation and quality agencies rarely focus on the specific content of discharge summaries, concentrating instead upon the mere presence or absence of the signed document [31]. Future studies that strengthen the connection between the quality of dysphagia therapy communication at the time of hospital discharge and dysphagia-specific patient outcomes are needed.

This study has some limitations that should be considered. The retrospective nature of this analysis makes it impossible for us to determine if some dysphagia therapies recommended by SLPs were purposefully omitted from discharge summaries by physicians who felt these recommendations were not appropriate for the patient at the time of hospital discharge. However, the remarkably high omission rate of dysphagia recommendations within discharge summaries and the high incidence of long-term dysphagia in subacute care populations [1, 13–15] make it unlikely that purposeful omissions explain the bulk of these findings. Second, this study was conducted in a single, large academic medical center in which most discharge summaries are authored by physician residents and in which most stroke patients are cared for within a dedicated stroke unit. This may limit the generalizability of our findings, especially considering that academic discharge summaries may differ from those created in community hospital settings and stroke units tend to focus strongly on dysphagia identification and treatment [72]. It is possible that hospital settings without these traits may have even lower rates of dysphagia therapy communication within discharge summaries.

In conclusion, discharge summaries within this study frequently omitted critical dysphagia therapy recommendations made by hospital-based SLPs, even in populations at very high risk for aspiration. Future studies should focus on both improving the discharge communication of dysphagia therapy information and the impact this improved discharge communication has on patient outcomes, especially in vulnerable subacute care populations who rely strongly upon the systems that surround them.

References

Robbins J, Gensler G, Hind J, Logemann JA, Lindblad AS, Brandt D, et al. Comparison of 2 interventions for liquid aspiration on pneumonia incidence: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:509–18.

Lipsky BA, Boyko EJ, Inui TS, Koepsell TD. Risk factors for acquiring pneumococcal infections. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146:2179–85.

Feinberg MJ, Knebl J, Tully J, Segall L. Aspiration and the elderly. Dysphagia. 1990;5:61–71.

Deutsch A, Fiedler RC, Granger CV, Russell CF. The Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation report of patients discharged from comprehensive medical rehabilitation programs in 1999. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81:133–42.

Deutsch A, Fiedler RC, Iwanenko W, Granger CV, Russell CF. The Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation report: patients discharged from subacute rehabilitation programs in 1999. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;82:703–11.

Holas MA, DePippo KL, Reding MJ. Aspiration and relative risk of medical complications following stroke. Arch Neurol. 1994;51:1051–3.

Kidd D, Lawson J, Nesbitt R, MacMahon J. Aspiration in acute stroke: a clinical study with videofluoroscopy. Q J Med. 1993;86:825–9.

Mann G, Hankey GJ, Cameron D. Swallowing function after stroke: prognosis and prognostic factors at 6 months. Stroke. 1999;30:744–8.

Smithard DG, O’Neill PA, England RE, Park CL, Wyatt R, Martin DF, et al. The natural history of dysphagia following a stroke. Dysphagia. 1997;12:188–93.

Buchner DM, Larson EB. Falls and fractures in patients with Alzheimer-type dementia. JAMA. 1987;257:1492–5.

Heruti RJ, Lusky A, Barell V, Ohry A, Adunsky A. Cognitive status at admission: does it affect the rehabilitation outcome of elderly patients with hip fracture? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:432–6.

Hickey A, Clinch D, Groarke EP. Prevalence of cognitive impairment in the hospitalized elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12:27–33.

Bucht G, Sandman PO. Nutritional aspects of dementia, especially Alzheimer’s disease. Age Ageing. 1990;19:S32–6.

Dray TG, Hillel AD, Miller RM. Dysphagia caused by neurologic deficits. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1998;31:507–24.

Fairburn CG, Hope RA. Changes in eating in dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 1988;9:28–9.

Priefer BA, Robbins J. Eating changes in mild-stage Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot study. Dysphagia. 1997;12:212–21.

Marik PE, Kaplan D. Aspiration pneumonia and dysphagia in the elderly. Chest. 2003;124:328–36.

Cowen ME, Simpson SL, Vettese TE. Survival estimates for patients with abnormal swallowing studies. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:88–94.

Carnaby G, Hankey GJ, Pizzi J. Behavioural intervention for dysphagia in acute stroke: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:31–7.

DePippo KL, Holas MA, Reding MJ, Mandel FS, Lesser ML. Dysphagia therapy following stroke: a controlled trial. Neurology. 1994;44:1655–60.

Hamidon BB, Abdullah SA, Zawawi MF, Sukumar N, Aminuddin A, Raymond AA. A prospective comparison of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and nasogastric tube feeding in patients with acute dysphagic stroke. Med J Malaysia. 2006;61:59–66.

Norton B, Homer-Ward M, Donnelly MT, Long RG, Holmes GK. A randomised prospective comparison of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and nasogastric tube feeding after acute dysphagic stroke. BMJ. 1996;312:13–6.

Whelan K. Inadequate fluid intakes in dysphagic acute stroke. Clin Nutr. 2001;20:423–8.

Garon BR, Engle M, Ormiston C. A randomized control trial to determine the effects of unlimited oral intake of water in patients with identified aspiration. J Neurol Rehabil. 1997;11:139–48.

Groher ME. Bolus management and aspiration pneumonia in patients with pseudobulbular dysphagia. Dysphagia. 1987;1:215–6.

Coleman EA. Falling through the cracks: challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:549–55.

Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297:831–41.

Roy CL, Poon EG, Karson AS, Ladak-Merchant Z, Johnson RE, Maviglia SM, et al. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:121–8.

van Walraven C, Seth R, Laupacis A. Dissemination of discharge summaries—not reaching follow-up physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:737–42.

Moore C, McGinn T, Halm E. Tying up loose ends: discharging patients with unresolved medical issues. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1305–11.

Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO): Standard IM.6.10, EP 7. http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/143FDA42-A28F-426D-ABD2-EAB611C1FD24/0/C_HistoryTracking_BHC_RC_20090323v2.pdf (2009). Accessed April 22, 2009.

Isaac DR, Gijsbers AJ, Wyman KT, Martyres RF, Garrow BA. The GP-hospital interface: attitudes of general practitioners to tertiary teaching hospitals. Med J Aust. 1997;166:9–12.

Meara JR, Wood JL, Wilson MA, Hart MC. Home from hospital: a survey of hospital discharge arrangements in Northamptonshire. J Public Health Med. 1992;14:145–50.

Pantilat SZ, Lindenauer PK, Katz PP, Wachter RM. Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists. Am J Med. 2001;111:15S–20S.

Sackley CM, Pound K. Stroke patients entering nursing home care: a content analysis of discharge letters. Clin Rehabil. 2002;16:736–40.

van Walraven C, Weinberg AL. Quality assessment of a discharge summary system. CMAJ. 1995;152:1437–42.

Nichol KL, Nordin J, Mullooly J, Lask R, Fillbrandt K, Iwane M. Influenza vaccination and reduction in hospitalizations for cardiac disease and stroke among the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1322–32.

Witt BJ, Brown RD Jr, Jacobsen SJ, Weston SA, Yawn BP, Roger VL. A community-based study of stroke incidence after myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:785–92.

Reker DM, Rosen AK, Hoenig H, Berlowitz DR, Laughlin J, Anderson L, et al. The hazards of stroke case selection using administrative data. Med Care. 2002;40:96–104.

Baxter NN, Habermann EB, Tepper JE, Durham SB, Virnig BA. Risk of pelvic fractures in older women following pelvic irradiation. JAMA. 2005;294:2587–93.

Kern LM, Powe NR, Levine MA, Fitzpatrick AL, Harris TB, Robbins J, et al. Association between screening for osteoporosis and the incidence of hip fracture. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:173–81.

Fisher ES, Wennberg JE, Stukel TA, Sharp SM. Hospital readmission rates for cohorts of Medicare beneficiaries in Boston and New Haven. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:989–95.

Foley N, Teasell R, Salter K, Kruger E, Martino R. Dysphagia treatment post stroke: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Age Ageing. 2008;37:258–64.

Olszewski J. Causes, diagnosis and treatment of neurogenic dysphagia as an interdisciplinary clinical problem. Otolaryngol Pol. 2006;60:491–500.

Curfman S. Dysphagia and nutrition management in patients with dementia: the role of the SLP. http://www.speechpathology.com/articles/article_detail.asp?article_id=262 (2009). Accessed April 8, 2009.

Brady A. Managing the patient with dysphagia. Home Healthc Nurse. 2008;26:41–6; quiz 47–48.

Logemann JA. Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders. 1st ed. Austin: Pro-Ed; 1983.

Groher ME. Dysphagia: diagnosis and management. 3rd ed. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1997.

Chernoff R. Geriatric nutrition: the health professional’s handbook. 3rd ed. Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2006.

Yorkston KM, Miller RM, Strand EA. Management of speech and swallowing in degenerative diseases. Austin: Pro-Ed; 1995.

ECRI: diagnosis and treatment of swallowing disorders (dysphagia) in acute care stroke patients. Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1999.

Martino R, Knutson P, Mascitelli A, Powell-Vinden B. Management of dysphagia in acute stroke: an educational manual for the dysphagia screening professional. Toronto: Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario; 2006. p. 1–48.

Stata Corporation. Stata statistical software. 10.1st ed. College Station: Stata Corporation; 2009.

SAS Institute. SAS statistical software. 9.1st ed. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2009.

Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, Wang L, Bradley EH. Consequences of inadequate sign-out for patient care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1755–60.

Dunn W, Murphy JG. The patient handoff: medicine’s Formula One moment. Chest. 2008;134:9–12.

Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(Suppl 1):i85–90.

Ong M, Bostrom A, Vidyarthi A, McCulloch C, Auerbach A. House staff team workload and organization effects on patient outcomes in an academic general internal medicine inpatient service. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:47–52.

Williams ES, Rondeau KV, Xiao Q, Francescutti LH. Heavy physician workloads: impact on physician attitudes and outcomes. Health Serv Manage Res. 2007;20:261–9.

Llewelyn DE, Ewins DL, Horn J, Evans TG, McGregor AM. Computerised updating of clinical summaries: new opportunities for clinical practice and research? BMJ. 1988;297:1504–6.

Lissauer T, Paterson CM, Simons A, Beard RW. Evaluation of computer generated neonatal discharge summaries. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66:433–6.

Archbold RA, Laji K, Suliman A, Ranjadayalan K, Hemingway H, Timmis AD. Evaluation of a computer-generated discharge summary for patients with acute coronary syndromes. Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48:1163–4.

van Walraven C, Laupacis A, Seth R, Wells G. Dictated versus database-generated discharge summaries: a randomized clinical trial. CMAJ. 1999;160:319–26.

Bado W, Williams CJ. Usefulness of letters from hospitals to general practitioners. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;288:1813–4.

Solomon JK, Maxwell RBH, Hopkins AP. Content of a discharge summary from a medical ward—views of general-practitioners and hospital doctors. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1995;29:307–10.

Tulloch AJ, Fowler GH, McMullan JJ, Spence JM. Hospital discharge reports: content and design. Br Med J. 1975;4:443–6.

van Walraven C, Rokosh E. What is necessary for high-quality discharge summaries? Am J Med Qual. 1999;14:160–9.

Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1822–8.

Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, Greenwald JL, Sanchez GM, Johnson AE, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:178–87.

Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, Jacobsen BS, Mezey MD, Pauly MV, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281:613–20.

Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–28.

Langhorne P, Pollock A. What are the components of effective stroke unit care? Age Ageing. 2002;31:365–71.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to UW Health Innovation Program staff Geoff Wodtke and Wen-Jan Tuan for data management and cleaning, Inna Larsen for administrative support, Colleen Brown and Kristin Slovenkay for manuscript formatting, and Peggy Munson for IRB assistance, and to Bruce Grau and Tim Kamps for assistance with data collection. Funding for this project was provided by the University of Wisconsin (UW) Hartford Center of Excellence in Geriatrics, the UW Health Innovation Program, and the UW Shapiro Summer Medical Student Research Fellowship. Dr. Kind is supported by a K-L2 through the NIH grant 1KL2RR025012-01 [Institutional Clinical and Translational Science Award (UW-Madison) (KL2)]. This project was also supported by the Community-Academic Partnerships core of the University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (UW ICTR), grant IUL1RR025011 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program of the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health. The UW Health Innovation Program provided assistance with IRB application, Medicare outcomes variable creation and linkage, data management and cleaning, and manuscript formatting. No other funding source had a role in the design or conduct data collection, management, analysis, or interpretation; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 3.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kind, A., Anderson, P., Hind, J. et al. Omission of Dysphagia Therapies in Hospital Discharge Communications. Dysphagia 26, 49–61 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-009-9266-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-009-9266-4