Abstract

The Fontana Lapilli deposit was erupted in the late Pleistocene from a vent, or multiple vents, located near Masaya volcano (Nicaragua) and is the product of one of the largest basaltic Plinian eruptions studied so far. This eruption evolved from an initial sequence of fluctuating fountain-like events and moderately explosive pulses to a sustained Plinian episode depositing fall beds of highly vesicular basaltic-andesite scoria (SiO2 > 53 wt%). Samples show unimodal grain size distribution and a moderate sorting that are uniform in time. The juvenile component predominates (> 96 wt%) and consists of vesicular clasts with both sub-angular and fluidal, elongated shapes. We obtain a maximum plume height of 32 km and an associated mass eruption rate of 1.4 × 108 kg s−1 for the Plinian phase. Estimates of erupted volume are strongly sensitive to the technique used for the calculation and to the distribution of field data. Our best estimate for the erupted volume of the majority of the climactic Plinian phase is between 2.9 and 3.8 km3 and was obtained by applying a power-law fitting technique with different integration limits. The estimated eruption duration varies between 4 and 6 h. Marine-core data confirm that the tephra thinning is better fitted by a power-law than by an exponential trend.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Plinian volcanism is the least studied type of basaltic activity and also potentially the most dangerous. Intense explosive eruptions (subplinian to Plinian events) have far-reaching impacts, due to their rapid onset, wide dispersal areas and high emissions of volcanic gases (Self et al. 1996; Cioni et al. 1999; Houghton et al. 2004). Basaltic magma can erupt explosively with a wide range of intensities and dispersals which are typically characterized by a Strombolian-Hawaiian style with typical mass eruptive rates of 103 to 105 kg s−1 (Simkin and Siebert 1994). However, four examples of basaltic Plinian eruptions have been well documented: the > 60 ka Fontana Lapilli and > 2 ka San Judas Formation from the Masaya area, Nicaragua (Williams 1983; Perez and Freundt 2006; Wehrmann et al. 2006), the 122b.c. eruption of Etna in Italy (Coltelli et al. 1998; Houghton et al. 2004; Sable et al. 2006a), and the 1886 Tarawera eruption in New Zealand (Walker et al. 1984; Houghton et al. 2004; Sable et al. 2006b; Carey et al. 2007). These eruptions had mass eruptive rates of 0.7–2.0 × 108 kg s−1. Several studies indicate that highly explosive eruptions can also occur with fluid magma not specifically of basaltic compositions (Freda et al. 1997; Palladino et al. 2001; De Rita et al. 2002; Watkins et al. 2002; Sulpizio et al. 2005). The recognition that many volcanoes occasionally erupt low-viscosity magma in such a powerful sustained fashion has come at a time when urban growth and volcano tourism bring increasing numbers of people to volcanoes such as Alban Hills, Etna and Vesuvius (Italy), Tarawera (New Zealand) and Masaya (Nicaragua; Chester et al. 2002).

The Fontana Lapilli deposit was first investigated by Bice (1980; 1985) and Williams (1983). In particular, Bice (1980; 1985) described the deposit as a uniform, unbedded, ungraded, basaltic lapilli bed. He identified Masaya as the source of this eruption, based on the direction of increasing thickness and on the chemical similarities with younger eruptions from Masaya. He also estimated the age of the Fontana Lapilli as between 25 and 35 ka, based on its stratigraphic position and radiocarbon ages of the younger Apoyo tephra (21 ka).

Williams (1983) first recognized the Plinian character of the widely dispersed basaltic fallout, which he called “Fontana Lapilli”. He described the deposit as a thick (2 to 6 m), well sorted, inversely graded scoria-fall deposit with a maximum thickness of 73 m on the Masaya caldera wall, suggesting a cone-building phase in an otherwise sheet-like geometry. He calculated a total erupted volume of 12 km3 and a maximum column height of 50 km, and suggested that the high eruption temperature of basaltic magma could explain the higher column height with respect to silicic analogues. He also estimated a volumetric eruption rate of 2 × 105m3 s−1 and an eruption duration of 2 h.

Wehrmann et al. (2006) re-examined the deposit in terms of internal stratigraphy and dispersal, defining new physical parameters for the eruption. In particular, they divided the deposit into seven different units and suggested that the climactic phase of the eruption was formed by a series of quasi-steady, distinct Plinian episodes repeatedly interrupted by phreatomagmatic pulses. Due to the poor exposure of the deposit, they also investigated three possible vent scenarios, suggesting that the most likely vent position is outside the Masaya caldera, in contrast with the initial interpretation of Williams (1983). Moreover, Wehrmann et al. (2006) correlated the thick deposit on the Masaya caldera rim recognized by Williams (1983) with a different, younger, basaltic eruption. They estimated a minimum total erupted volume of 1.4 km3, a maximum column height of 24 to 30 km, a mass eruptive rate of around 2 × 108 kg s−1 and a wind velocity between 0 and 30 m s−1.

Based on marine gravity cores from the Pacific seafloor off of Central America, Kutterolf et al. (2008a) estimated the age of Fontana Lapilli as > 60 ka, assuming a uniform pelagic sedimentation rate. This age is considerably older than the > 30 ka suggested by Bice (1985) and supports the conclusion of Wehrmann et al. (2006) that the eruption vent was outside the Masaya caldera. Including the marine-core data in their calculation, Kutterolf et al. (2008b) determined a total erupted volume of 2.7 km3.

In this paper we detail the medial stratigraphy and dispersal of the Fontana Lapilli as well as the grain size and componentry of the deposits. We use these data to develop an eruption model and to constrain parameters such as magnitude, intensity and duration of the main Plinian phase. We also use the marine-core data from Kutterolf et al. (2008a) to discuss the most probable dispersal trend of the deposit.

Stratigraphy and distribution of the deposit

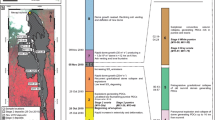

The Fontana Lapilli (Williams 1983), equivalent to Masaya Lapilli Bed of Bice (1985) and to Fontana Tephra of Wehrmann et al. (2006), is a thick, widely dispersed, black scoria-fall deposit. It is well exposed only in its medial, northern and northwestern sectors between Masaya caldera and the outer suburbs of Managua, where it is more than 1 m thick (Fig. 1). No exposures exist in any of the other medial sectors or in the proximal area, making it difficult to constrain the exact dispersion of the deposit and the location of the vent. Limited exposure is the result of recent volcanic activity from Masaya volcano and Apoyo caldera which have partially buried the Fontana Lapilli deposit.

Isopach maps (in cm) of a unit B and b unit C (opening eruptive stage) and c units D+E+F (main Plinian stage). Black circles indicate examined outcrops. Two sampled outcrops (FL1 and FL2, about 6 and 13 km from vent position) are plotted as a black square and hexagon respectively. Dashed lines are extrapolated contours. Open triangle marks the most likely vent position for main Plinian phase, after Wehrmann et al. (2006)

Wehrmann et al. (2006) divided the deposit into seven units (A to G) based on bedding characteristics, presence of interspersed white ash-bearing layers (which from now on we will simply refer to as white layers) and visual estimations of clast componentry. We have slightly revised the units after a detailed analysis of the products (based on grain size and componentry analysis), so that we now consider the eruption in the context of three main stages: the opening stage (units A, B and C), the main stage (units D, E, F and lower G) and the closing stage (upper unit G). Figure 2 illustrates the stratigraphy of our most studied outcrop (FL1); a schematic stratigraphic section of the same site is shown in Fig. 3 and its location in Fig. 1. We identified and correlated units from different outcrops based on the presence of the white layers, macroscopic characteristics (i.e. colour and size of clasts), and differences in lithic content and type.

Photographs of Fontana Lapilli deposit at FL1 outcrop, about 6 km from the possible vent location (location at Fig. 1), illustrating contacts between the different units and the presence of white layers

a Schematic stratigraphy of Fontana Lapilli deposit at FL1, with locations of samples used for the componentry analysis shown in Fig. 6 given by the numbers 1–10 on right side of the stratigraphic column. Greek letters on the left hand side of the column locate white layers. b Variation in median diameter \(\left( {{\text{Md}}_{\text{ $ \phi $ }} } \right)\) and c standard deviation coefficient \(\left( {\sigma _{\text{ $ \phi $ }} } \right)\) with stratigraphic height of the grain size distributions. Open diamonds represent samples taken from the white layers, while the black diamonds represent all the other samples

Opening stage: units A, B and C

The opening stage of the Fontana Lapilli starts with unit A, which is characterized by a thin, shower-bedded, coarse ash and fine scoria-lapilli deposit poor in wall-rock lithic clasts. This unit is dm-thick at the most proximal sites but mm-thick or absent across the rest of the dispersal area. Unit A is overlain by unit B, a moderately sorted, black, highly vesicular scoria-fall deposit typically containing 3–4 wt% lithics of fresh black lava fragments. Unit B is significantly more widely dispersed than unit A. In the most proximal outcrops it is 50–100cm thick (Fig. 1a) and exhibits weak internal bedding with alternating inversely and normally graded layers at the base which are moderately-to-poorly sorted, and a massive, better sorted and coarser, upper part. With distance from source, unit B is more massive, lacking obvious internal bedding.

Unit C is characterized by two main beds, each composed of poorly sorted, grey, scoriaceous lapilli with an upward increase in ash content. Although unit C is generally planar-bedded, at one outcrop (FL1), the lower bed has pinch-and-swell stratification (Fig. 2b). Lithics form 2–3 wt% of unit C and consist of fresh and altered basalt fragments. Non-juvenile, silver pumice lapilli are also present in this unit, their abundance increases upward reaching a maximum of > 5vol%. They are highly vesicular with strongly elongated vesicles. Even though the silver pumice is only present in unit C and in the bottom part of unit D, it is a crucial marker that helps distinguish the Fontana Lapilli deposit from younger scoria-falls. It has a unique chemical composition which lies at the boundary between dacite and trachyte and has a higher total alkali content (> 8 wt%) with respect to all the pumice deposits found in west-central Nicaragua (Kutterolf et al. 2007).

Wehrmann et al. (2006) found a cross-bedded, poorly sorted, grey, fine ash layer south of the possible vent position and interpreted it as a correlative of unit C. However, better characterization of the stratigraphy shows that the south sector is dominated by younger tephra deposits (Kutterolf et al. 2007), with no evidence of the Fontana Lapilli deposit.

Main stage: units D, E, F and lower G

This eruptive stage produced the middle part of the Fontana Lapilli deposit, which is present at all exposures and reaches a maximum thickness of about 3 m in proximal locations (Fig. 1c). It is composed of numerous, moderately sorted, massive-to-weakly stratified, non-graded, dark grey-to-black, highly vesicular scoria-lapilli beds. It was divided into four different units (units D, E, F and G) by Wehrmann et al. (2006), based mainly on a slight difference in colour (i.e. the colour of unit E is typically lighter than that of both units D and F) and on the presence of two distinctive white layers, each a few centimetres thick (i.e. white layers α and γ in Fig. 3).

The lower part of unit G is a massive, non-graded, coarse-grained, black scoria-lapilli bed. Apart from the presence of a thick white layer (γ in Fig. 3), the lower part of unit G cannot be distinguished from unit F. In contrast, the upper part of unit G is different to its lower part, being generally finer, crudely stratified, dark-grey-to-black and slightly less sorted. Based on these different characteristics, we divided unit G of Wehrmann et al. (2006) into “lower unit G” and “upper unit G”, the two being separated by white layer ɛ (Fig. 3). Given these differences, we consider the upper part of unit G to represent a third (and closing) eruption stage. Unit G of Wehrmann et al. (2006) is often partially eroded, and in some outcrops even lower unit G is not preserved.

Only weak fluctuations in type and abundance of lithic clasts are present through the middle Fontana Lapilli eruptive sequence. Silver, highly vesicular pumice clasts, similar to those in unit C, are present but only at the bottom of the deposit (in unit D). Accidental clasts are fresh and altered lava fragments whose abundance ranges between < 1 and 3 wt%.

Closing stage: upper unit G

The upper part of the Fontana Lapilli deposit (upper part of unit G of Wehrmann et al. 2006) consists of moderately stratified, dark-grey-to-black scoria-lapilli beds alternating with fine and coarse lapilli layers each a few centimetre thick. At least six white layers are present throughout the upper G deposit (ɛ to κ, Fig. 3). Lithics are generally 1–2 wt% and consist of altered and fresh basalt fragments. The top is everywhere eroded and commonly altered by soil-forming processes, precluding correlation of individual layers and consistent isopach mapping across the dispersal area.

White layers

A distinctive feature of the Fontana Lapilli is the presence of at least ten continuous white ashy layers in the stratigraphy. Most of these layers are distinctive markers that maintain consistent stratigraphic position and appearance across all of the outcrops, even though in some cases they are difficult to trace across a single outcrop. At FL1, they consist of sharply bounded layers, typically 1 to 3cm thick, which generally contain 10–15 wt% of ash-sized material (Figs 2 and 3). In two samples of upper unit G (i.e. white layers ɛ and ζ in Fig. 3), the ash content is up to 25 wt%. The ash is present both as thick coatings on juvenile and lithic lapilli and in the interstices between clasts. In some places, the white ash also occurs in irregular pods and lenses within the scoria deposit, commonly associated with vegetation roots. Even though the white layers are commonly ash-rich, continuous, and correlateble across all outcrops, they can not be defined as “ash partings” sensu stricto. In fact, the grain size of the deposit does not change significantly across these ash-rich layers, leading us to consider them as intercalations of ash in the otherwise massive and coarser scoria units, rather than conventional, moderately-to-well-sorted “ash partings” resulting from pauses in the eruption sequence.

Dispersal characteristics

We present here revised isopach maps for part of the opening stage (units B and C) and part of the main stage (units D+E+F; Fig. 1). We exclude unit A, because it mainly appears in pockets at the scale of the outcrops, as well as unit G, because of the issues of partial erosion discussed above. Units B and C reflect a progressive shift in eruption conditions at the start of the eruption, and are characterized by different dispersal directions. In contrast, Wehrmann et al. (2006) showed that units D, E, and F have the same dispersal axis. For this reason, and because of grain size homogeneity discussed below, we consider D, E and F together (i.e. D+E+F). The limited availability of outcrops to the northwest sector, and the absence of proximal exposures, preclude both the closure of the isopach contours and the precise identification of the vent site. On each map in Fig. 1, we plot the most likely vent position for units D, E and F as suggested by Wehrmann et al. (2006). However, the dispersal pattern of the isopachs for units B and C appears to be different from that for D+E+F.

Grain size

Grain size data of sixty-three selected samples from the studied outcrops are presented in Figs. 3 and 4 and in Table 1. Due to the poor exposure of the deposit outside the northwestern sector, detailed sampling and analysis were completed only at outcrops FL1 and FL2 (Fig. 1). Grain size analyses involved a combination of sieve analysis (down to 63μm) by hand, to avoid breakage of pyroclasts, and particle image analysis using a Malvern PharmaVision 830 automated optical device. Based on digital image analysis and automated microscopy, the PharmaVision 830 device measures both particle size and particle shape. Specifically, the 1 mm–5μm fraction is constrained using the ‘width shape parameter’. This is defined as the maximum length of all the possible lines from one point of the perimeter to another point on the perimeter projected on the minor axis obtained from the image analysis (www.malvern.com). This parameter seems to give the best result when combined with hand-sieved data (Volentik unpublished data).

Plot of median diameter \(\left( {{\text{Md}}_{\text{ $ \phi $ }} } \right)\) versus standard deviation coefficient \(\left( {\sigma _{\text{ $ \phi $ }} } \right)\) for the grain size samples from FL1 and FL2. The pyroclastic fall and flow fields are defined following Walker (1971)

The grain size distribution of most samples is unimodal, ranging between −5ϕ and 7ϕ where ϕ = −log2 d, d being the particle diameter in millimetre scale. The white layers and unit C samples have, instead, a weak bimodal to polymodal distribution (Table 1). Even in these samples, however, the fraction < 1 mm is generally 15 wt% or less, and only rarely it is > 25 wt%; the percentage of fine ash (< 63μm) is normally less than 1 wt%.

Tephra deposits can be characterized using parameters defined by Inman (1952), \({\text{Md}}_{\text{ $ \phi $ }} \) (median diameter) and \(\sigma _{\text{ $ \phi $ }} \) (sorting). For Fontana Lapilli, median diameters Mdϕ range between −3.2ϕ and −0.9ϕ (Fig. 4 and Table 1), with the higher values (i.e. smaller grain sizes) characteristic only of samples from the opening and closing stages and of samples from distal outcrop FL2. In fact, \({\text{Md}}_{\text{ $ \phi $ }} \) tends to decrease downwind but relatively slowly (compare FL1 and FL2 in Fig. 4), attesting to the wide dispersal of the deposit. Most of the samples are moderately sorted, with a standard deviation \(\sigma _{\text{ $ \phi $ }} \leqslant 1.6\). Sorting does not vary significantly between the FL1 and FL2 sites. Many samples from unit C and the white layers are, however, poorly sorted \(\left( {\sigma _{\text{ $ \phi $ }} \geqslant 2} \right)\), due to a higher abundance of ash (Figs. 3 and 4). In most places, there is no significant change in grain size or physical appearance of the lapilli population at the onset of the white layers, where an increase in fine material occurs (Fig. 5).

Grain size analysis of lapilli samples around two white layers (layers α and β, Fig. 3) expressed in terms of median diameter \(\left( {{\text{Md}}_{\text{ $ \phi $ }} } \right)\) and standard deviation \(\left( {\sigma _{\text{ $ \phi $ }} } \right)\), and weight percent of the < 1 mm and < 63 μm fraction (Walker 1983). Values for white layers are shaded. The median diameter does not vary significantly, but the ash portion ( wt% < 1 mm) is higher in the white layers

We also note that most of the largest scoria clasts are broken, probably because of impact with the ground. This leads to a reduction of the median grain size. Figure 3 shows that the grain size parameters do not vary significantly from upper unit D to lower unit G, remaining relatively coarse throughout.

Componentry and juvenile clast morphology

Clasts down to 0ϕ (1 mm) were analyzed for componentry in ten representative samples from FL1 (Fig. 6). These size classes represent > 90 wt% of most samples. For two samples of white layers, α and γ, it was possible to analyze only the classes down to −1ϕ (2 mm), because the thick white coating made it difficult to discriminate the nature of the small clasts. The 1 mm fraction was also observed in more detail using a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) at University of Geneva (Switzerland).

Histograms of the grain size distribution and componentry for the ten samples from outcrop FL1 (Fig. 3)

We define three types of clasts based on colour, morphology and crystallinity, as well as bubble abundance and shape: juvenile clasts with sub-angular shape, fluidal/elongated juvenile clasts and wall-rock lithics (which also includes the silver pumice clasts). The juvenile components predominate in the deposit, with the lithic content ranging from 0.5 to 4.0 wt%. Most of the juvenile clasts have a homogenous texture, but a few have glassy, quenched rims. Juvenile clast textures are aphyric to subaphyric with rare plagioclase and pyroxene phenocrysts. Ragged juvenile clasts with sub-angular shapes are generally most abundant. They consist of a variety of morphologies, from sub-equant clasts with a smooth glassy surface, to blocky, highly angular sideromelane and tachylite. Clasts with some angular and sharp edges were probably formed due to brittle fragmentation when they hit the ground or other pyroclasts (Houghton and Smith 1993). Most of the particles are highly vesicular, with vesicle shapes ranging from spherical to irregular colliform. Numerous coalesced vesicles are present (Fig. 7). Many of the fluidal/elongated clasts are glassy, and most have highly elongated vesicles parallel to the long axis of the pyroclast with fairly thick vesicle walls (Fig. 7). Poorly or non-vesicular clasts are rare. The fluidal clasts are scarcely present in the −5ϕ and −4ϕ grain size classes but their abundance increases at smaller particle sizes. Even though lithic abundance is low, several different typologies have been recognized through the stratigraphy. Fresh and hydrothermally altered basalt predominates, but silver pumice xenoliths and rare holocrystalline lithic clasts have also been found.

Scanning electron microscope images of sub-angular (top images) and fluidal juvenile (bottom images) clasts. All clasts are highly vesicular; but the sub-angular clasts have vesicles with spherical-to-irregular shapes, whereas the fluidal clasts generally have elongated vesicles orientated parallel to the long axis of the pyroclasts

Figure 6 shows how the componentry varied during the eruption. The sample from unit B is unusual because it has a high content of both fluidal/elongated juvenile clasts and lithics (4 wt%) of dark grey, poorly vesicular, fresh lava fragments. While the fluidal juvenile clasts tend to decrease with time (the sample from unit D being an exception), the lithic content shows no linear trend, fluctuating weakly through the section. However, in the middle and upper part of the stratigraphy, the lithic content is relatively high (around 3 wt%) in two of the three most pronounced white layers (γ and δ; samples 7 and 8 in Fig. 6).

Characterization of eruption physical parameters

Erupted volume: on-land data

To estimate the erupted volume, we first consider only the land-based field data (Fig. 1) and then compare them with marine-core data from Kutterolf et al. (2008a) in order to constrain better the rate of deposit thinning.

We calculated only erupted volume for units D+E+F from the isopach map in Fig. 1c, using the vent location suggested by Wehrmann et al. (2006). This was necessary because of the limited exposure of the deposit, the uncertainty of vent location, and the possible migration of the vent during the eruption of unit B to units D+E+F. For the volume calculation we applied both exponential and power-law fitting techniques. The exponential method was introduced by Pyle (1989), whereas the use of a power-law fit was supported by numerical simulations and evidence from well preserved tephra deposits (Bonadonna and Houghton 2005). The best-fit equations for the two methods are, respectively:

where T is the thickness, T o is the maximum thickness, A is the area, k is the slope of the exponential fit, T pl is the power-law coefficient and m is the power-law exponent.

Because of the impossibility of integrating the power-law curve between values of zero and infinity, we need to choose two finite integration limits. We define \(A_{\text{o}}^{{{\text{1}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\text{1}} {\text{2}}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\text{2}}}} \) as the proximal integration limit, which corresponds to the distance of the maximum thickness of the deposit, and \(A_{{\text{dist}}}^{{{\text{1}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\text{1}} {\text{2}}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\text{2}}}} \) as the outer integration limit, which corresponds to the distance of the extent of the deposit.

Figure 8 compares exponential and power-law best fits for the main eruptive stage of Fontana Lapilli. The proximal and distal trends are poorly constrained due to the lack of outcrops. As a result, the two curve-fitting methods lead to very different results (Table 2). Integration of the exponential fit gives a total erupted volume of 0.6 km3, whereas integration of the power-law fit gives a volume between 2.9 and 5.5 km3, by varying the extent of the deposit between 300 and 1,000 km from the vent (\(A_{{\text{dist}}}^{{{\text{1}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\text{1}} {\text{2}}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\text{2}}}} \) integration limit; Table 2). However, marine-core data suggest that a 1,000 km extent for the deposit may be too large; the data from Kutterolf et al. (2008a) show a likely extent of ≤ 500 km as the deposit is 2cm thick at ≤ 260 km. Given that the variation of \(A_{\text{o}}^{{{\text{1}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\text{1}} {\text{2}}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\text{2}}}} \) does not affect the final result, we used \(A_{\text{o}}^{{{\text{1}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\text{1}} {\text{2}}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\text{2}}}} \) equal to 0.3 km for all calculations.

The bulk density of samples from units D+E+F was measured at FL1. Results ranged from 700 ± 50 kg m−3 for unit F to 750 ± 30 kg m−3 for unit E to 760 ± 65 kg m−3 for unit D (each value is an average of eight measurements), giving an average of 735 ± 80 kg m−3 for the whole of D+E+F. Due to the impossibility of measuring density in distal and proximal areas, we have used this value to estimate the total erupted mass of the combined units D+E+F, which varies between 4.4 × 1011 and 4.0 × 1012 kg depending on the technique and the assumptions used to obtain volume (Table 2).

Erupted volume: marine-core data

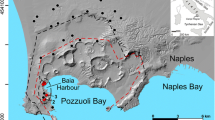

In order to constrain better the deposit thinning, we considered data from the eight marine gravity cores obtained from the Pacific seafloor off the west coast of Nicaragua by Kutterolf et al. (2008a). The marine-core data come from both primary ash layers and ash pods (see Table 3 for more details). The ash-layer correlation between cores and parental Fontana Lapilli tephra on land was made by Kutterolf et al. (2008a) using stratigraphic, lithologic and compositional criteria. The Fontana Lapilli appears as the oldest mafic deposit from Masaya area found in the core data. It is characterized by relatively higher TiO2, K2O and Zr contents and higher sideromelane/tachylite ratio with respect to other basaltic deposits of the same area (Kutterolf et al. 2007; Kutterolf et al. 2008a). Figure 9 shows the location of the marine-core collection data points and three possible 2-cm isopachs (i.e. models I, II and III).

Marine-core location map with three possible 2-cm isopachs. The figure also shows the 50-, 150- and 250-cm isopachs (in red) and the vent location (open triangle) from Wehrmann et al. (2006). Dots and numbers indicate location of each marine core and thickness of deposit in centimetres at each core site

Due to the lack of any internal stratigraphy in the marine core (Kutterolf unpublished data) and because it is impossible to estimate the thickness of unit G even on land, we consider all the Fontana marine-core layers as equivalent to units D+E+F. Such an assumption is likely to be an overestimate of the volume. Moreover, given the lack of data and their distribution in a limited sector, we examined three possible tephra dispersals in order to close the isopach line of 2-cm thickness. Model I represents the isopach derived by simply following the same dispersal axis as the on-land isopachs (Figs. 1c and 9). Model II is based on the empirical method of ellipses of Sulpizio (2005). This method is based on the assumptions that distal isopachs have an elliptical shape with the same eccentricity and the same dispersal axis as the proximal isopachs. Model III follows the isopach contours drawn by Kutterolf et al. (2008b) and represents a hypothetical dispersal of ash in the case of a change of wind direction during the eruption as sometimes observed (e.g. at Mount St. Helens in 1980; Sarna-Wojcicki et al 1981).

For the calculation of erupted volume we applied both the exponential and power-law fitting techniques as well as the empirical method of \(\sqrt {A_{{\text{ip}}} } \) with one distal isopach (Sulpizio 2005). This last method is based on an empirical correlation between the break-in-slope distance (\(\sqrt {A_{{\text{ip}}} } \)) and the proximal thinning rate (k prox) for the case of availability of proximal-medial data and only one distal isopach, so that:

Table 4 and Fig. 10 show that the results from power-law fitting for model I are in reasonable agreement with the power-law results obtained for the on-land data. In contrast, models II and III show a slightly different trend resulting in larger and smaller volumes, respectively.

Plot of log thickness versus square root of area for the Fontana Lapilli deposit considering both on-land and marine-core data. The field data are represented by black points, while open red square represents the position of break-in-slope following the \(\sqrt {A_{{\text{ip}}} } \) empirical method of Sulpizio (2005; Eq. 3 in the text). The graph shows exponential and power-law trends for on-land data (black lines), exponential (red lines) and power-law trends (grey lines) obtained using the three possible isopach contours of on-land + marine-core data points (models I, II and III)

Column height

Maximum column height (H) was estimated from lithic isopleth maps by applying the method of Pyle (1989). This method is based on the calculation of parameter b c (the maximum clast half-distance) and on the predicted height of the neutral buoyancy level H b for conditions of no wind. The dimension of the “maximum clast” was calculated from the average of the three principal axes of the five largest clasts measured from three different units by Wehrmann et al. (2006; units D, E and F). This gave a b c value for unit D of 3.7 km corresponding to a maximum column height of 32 km. Results can be compared with the method of Carey and Sparks (1986) which is based on downwind and crosswind extent of isopleth lines applied by Wehrmann et al. (2006). Comparison between these two method shows that both give a maximum height for unit D of 30–32 km, with the difference in the results being < 10%.

Mass eruptive rate and eruption duration

Following Wehrmann et al. (2006), we estimated the mass eruptive rate averaged over units D+E+F by applying the equation of Wilson and Walker (1987). However, the Wilson and Walker (1987) equation is strictly valid only for a plume temperature of about 1,120K, more appropriate for silicic magma. Considering a temperature of 1,300K, Wilson and Walker (1987) can be modified, according to Sparks (1986), so that:

H being the maximum column height and M o the mass eruptive rate. Considering the maximum column height of 32 km obtained for units D+E+F yields a mass eruptive rate of 1.4 × 108 kg s−1. Based on this value, the corresponding minimum eruption duration varies between 53 min and 8 h 6 min (obtained dividing the total erupted mass by the mass discharge rate; Table 2).

Eruption style

Only units D+E+F are sufficiently well constrained to calculate the thinning half-distance b t (Fig. 11 and Table 5). This was calculated following Pyle (1989) where b t is the distance over which the deposit halves in thickness. In the medial region (area ½ of 6–16 km), b t is 2.6 km. Other well described basaltic Plinian fall deposits have values of 2.7 km (Etna 122b.c.), 2.6 km (San Judas Formation) and 4.3 km (Tarawera 1886; Table 5). These values are also typical of the medial portions of the deposits of historical silicic Plinian eruptions of moderate intensity, e.g. Mount St Helens 18 May 1980 (3.2 km), Askja 1875 (3.5 km), Quizapu 1932 (5.9 km) or Hudson 1991 (6.8 km). However, these are significantly smaller than those of the most powerful, historical silicic eruptions, e.g. Pinatubo 1991 (9 km) and Novarupta 1912 (16 km; Table 5). The Plinian character of the main phase of the Fontana Lapilli deposit is confirmed by the classification of Pyle (1989).

Plot of log thickness versus square root of area of the Fontana eruption compared with thinning trend for tephra deposits produced by other highly explosive eruptions. These include: subplinian [Mount St. Helens (MSH) 22 July 1980 and Ruapehu 17 June 1996]; silicic Plinian (Askja D 1975, Hudson 1991, Minoan 3.6 ka, MSH 18 May 1980, Quizapu 1932, Taupo 186 a.d.); and basaltic Plinian (Fontana Lapilli, San Judas Formation, Tarawera 1886). Data are from: Sparks et al. 1981 [Askja D]; Scasso et al. 1994 [Hudson]; Pyle 1990 [Minoan eruption]; Sarna-Wojcicki et al. 1981 [Mount St. Helens]; Hildreth and Drake 1992 [Quizapu]; Bonadonna and Houghton 2005 [Ruapehu]; Perez and Freundt 2006 [San Judas]; Walker et al. 1984 [Tarawera]; Walker 1980 [Taupo]

The physical parameters of units A, B and C cannot be constrained due to the high uncertainty regarding vent position and possible closure of isopach contours, but we can nonetheless compare thinning rates along the dispersal axis in a manner analogous to that of Houghton et al. (2004) and Sable et al. (2006b). The thinning half-distance over 11 km is 2, 5 and 6 km for units B, C and D+E+F respectively indicating a slightly lower dispersal of the opening stage compared to the main stage. Unfortunately, it is impossible to quantify the intensity of the final stage of Fontana Lapilli eruption, because the upper part of unit G is commonly eroded. However, the stratigraphy and grain size data from our studied sections suggest that the sustained high plume became both slightly weaker and less stable in upper G times, resulting in the fluctuations of grain size visible in Fig. 3.

Discussion

Eruption model: opening stage

The early stage of the eruption was marked by an escalating, moderately explosive eruption phase characterized by a growing but unstable eruption column and relatively limited dispersal. The abundance of fluidal clasts and the weak dispersal of unit A suggest that the beginning of the eruption was characterized by a fluctuating fountain-like jet. The eruption evolved, next depositing a thick, highly vesiculated, black scoria fall (unit B), which was more widely dispersed. However, this phase was less sustained and intense with respect to the main phase of the eruption. In fact, the bedding in unit B in the most proximal localities reflects a pulsating and unstable character to this early portion of the high eruptive plume. In addition, the abundant juvenile clasts with elongated bubbles present in unit B are generally glassy with a quenched rim and fluidal shape. This characteristic suggests that bubble elongation was not driven by viscous shearing during magma rise through the conduit but instead by shearing in the gas jets after fragmentation, as usually happens in typical Hawaiian-fountaining eruptions or, more generally, in basaltic eruptions characterized by high eruptive temperature and moderate explosivity (Wentworth and MacDonald 1953; Walker and Croasdale 1972; Head and Wilson 1989; Vergniolle and Mangan 1999). The presence of only fresh lava lithics in unit B, in contrast to the altered lithics present in the main phase, could suggest a shallower fragmentation level in the conduit, a progressive establishment of a stable conduit, or a different vent position with respect to the main phase (units D+E+F), which would also be consistent with the different geometry of the isopachs between B and D+E+F (Fig. 1).

The upper part of the opening stage (unit C) is characterized by the highest concentration of ash at FL1 relative to the other units and its thinning rate suggests a magnitude for C between that of B and D+E+F. This indicates a change in eruption style with a more efficient magma fragmentation mechanism. However, the lack of a significant lithic fraction in unit C and the absence of scoria clasts with cracked, quenched rims tend to exclude a major involvement of external water in the eruption dynamics as proposed by Wehrmann et al. (2006). Furthermore, we found no pyroclastic surge deposits in the south-western sector of Masaya caldera which could be associated with unit C, as Wehrmann et al. (2006) suggested. In summary, unit C represents a moderately explosive eruption phase which generated a relatively high amount of ash and scoria-lapilli clasts.

Eruption model: main stage

The main part of the Fontana Lapilli is a coarse, massive, thick, widely dispersed, highly vesicular scoria-lapilli bed. It had a Plinian intensity with dispersal characteristics similar to other basaltic, and many silicic, Plinian eruptions (Figs. 11, 12 and Table 5). The lack of well defined bedding and of a significant variation in either grain size or componentry suggests a sustained event characterized by a stable plume from a single source vent. This contrasts with the interpretation of Wehrmann et al. (2006) who proposed several shorter Plinian episodes repeatedly interrupted by phreatomagmatic pulses. This phase includes not only units D, E and F, which we were able to identify because of the interbedded white layers, but also the lower part of unit G. However, as mentioned before, it was impossible to consider unit G in our analysis because it is partially eroded, or even totally missing, in several locations. As a result, the whole Plinian phase lasted for a longer period and erupted more material than estimated for D+E+F alone (Tables 2 and 4).

Classification scheme for tephra deposits introduced by Pyle (1989) showing the Plinian character of the main phase of the Fontana Lapilli deposit, here represented by black diamond. The error bar is related to three different b c values obtained from the dimension of the “maximum clast” calculated from three different units (unit D, E, F) by Wehrmann et al. (2006)

Eruption model: closing stage

The upper part of unit G at site FL1 is generally finer, weakly stratified and slightly less sorted than the products of the main Plinian phase, and exhibits an alternation of fine and coarse lapilli layers. Upper unit G indicates fluctuations, instability and weakening of the eruption column during an unsteady, and probably less intense, closing phase. However, the deposit is eroded and altered in its upper part, making it impossible to determine its dispersal.

Dispersal and vent position

The different dispersal pattern of the units B, C and D+E+F (Fig. 1) may be the result of either a change in wind direction or a vent migration during the eruption. For the difference to have been due to shifting winds, the wind direction would have had to have shifted from west during the emplacement of unit B to the northwest during the emplacement of unit D+E+F. However, the dispersal of units B and C is not consistent with the position of the vent considered by Wehrmann et al. (2006) for unit D+E+F. In fact, in order to use the same vent position, the corresponding isopach map would show a very sharp dispersal shift in the proximal area that could not be explained even with sedimentation from a weak plume.

In contrast, the dispersal of units B and C is more consistent with a wind direction blowing toward the northwest and a vent migration from west–southwest to east–northeast (by about 5 km). Multiple vent scenarios are common in other basaltic explosive eruptions. As an example, the eruption of Tarawera 1886 was fed by a 17 km-long chain of craters (Walker et al. 1984; Houghton et al. 2004). However, the direction of vent migration observed for Fontana is not in good agreement with the current tectonic features of the area which is characterized by a system of faults oriented north–northeast and north, forming the Managua Graben (Fig. 1) (La Femina et al. 2002; Girard and van Wyk de Vries 2005). However, the 60 ka age of Fontana Lapilli (Kutterolf et al. 2008a) is considerably older than the ages estimated for both Masaya volcano and the Managua Graben (i.e. > 25–30 ka; Girard and van Wyk de Vries 2005). As a result, the formation of the Managua Graben and Masaya is likely to have occurred long after the eruption of the Fontana Lapilli, so that more recent events could have erased any evidence of previous fault lineaments that may have controlled vent location during the Fontana eruption.

Implications for the general mechanism of basaltic Plinian eruptions

Our characterization of the physical parameters of the Fontana Lapilli eruption show that the main Plinian phase lasted as long as the 1886 basaltic Plinian eruption of Tarawera (i.e. 5 h), and it had comparable mass eruptive rate and column height. Eruption rate and column height of Tarawera were > 2 × 108 kg s−1 and 28–34 km, respectively (Walker et al. 1984; Carey and Sparks 1986) comparing with 1.4 × 108 kg s−1 and 32 km for Fontana. In contrast, the 122b.c. basaltic Plinian eruption of Etna had a slightly lower mass eruptive rate and column height of > 7 × 107 kg s−1 and 24–26 km, respectively (Coltelli et al. 1998).

The low content of lithics and ash in all units at FL1 and FL2 and the lack of thermal cracks in the juvenile clasts suggest no major involvement of external water in the dynamics of the eruption. This contrasts with all other studied basaltic Plinian eruptions (i.e. Etna 122b.c., San Judas, and Tarawera 1886), in which the “dry” Plinian phase was preceded and/or followed by phreatomagmatic events (Walker et al, 1984; Coltelli et al. 1998; Houghton et al. 2004; Perez and Freundt 2006). However, the lack of the uppermost part of the deposit precludes speculation about the possible conditions during the closing phase.

This eruption therefore appears somewhat drier then its basaltic Plinian counterparts. The high eruption temperature, suggested by the glassy texture of many juvenile products and intense bubble coalescence (Costantini, unpublished data), certainly played an important role in the eruption dynamics, enhancing plume buoyancy and therefore facilitating the wide dispersal of the tephra.

Hazard implications

Basaltic Plinian eruptions are particularly dangerous, because eruption precursors are not yet well understood and thus may be misinterpreted or overlooked. Also, the rapid ascent rate of basaltic magma during basaltic Plinian eruptions means that the time between onset of unrest and eruption may be as short as a few hours (Houghton et al. 2004). Furthermore, several basaltic, low-viscosity explosive volcanoes are close to populated cities making the understanding of the risk from this type of eruption crucial to safety and development of these communities (e.g. Alban Hills, Etna and Vesuvius, Italy; Kīlauea, USA; Tarawera, New Zealand; Cerro Negro and Masaya, Nicaragua).

The Fontana Lapilli eruption is an extreme, but real, example of how basaltic magma can erupt explosively, depositing packages of scoria lapilli and ash more than 1 m thick in less than a day at about 6 km from the vent. If erupted today, these deposits would cover the largest city in Nicaragua (Managua) and its surrounding area. The Masaya area also produced four other large basaltic eruptions during the past 6000 years (Freundt et al. 2006; Perez and Freundt 2006), characterized by pyroclastic fall (i.e. San Antonio Tephra, La Concepción Tephra and San Judas Formation) and phreatomagmatic surge deposits (i.e. Masaya Tuff), testifying to the high potential risk posed by future basaltic explosive eruptions in this area. Furthermore, the possible fissure opening and vent migration that may have accompanied the Fontana Lapilli eruption means that a widely distributed fallout area must be considered when compiling a hazard assessment. In carrying out such assessments, constraints on plume height, eruption duration, dispersal area, vent location and erupted mass are critical elements in hazard assessment during Plinian eruptions (Connor et al. 2001; Cioni et al. 2003; Bonadonna 2006).

Application of marine-core data

The benefits of using marine-core data for volume estimates for deposits that extend offshore have been shown by Paladio-Melosantos et al. (1996). Even for recent, well exposed deposits Paladio-Melosantos et al. (1996) showed how volume can be underestimated when considering only dispersal on land. For the Pinatubo 1991 eruption a volume of 1.7 km3 can be calculated for the climactic phase using only the on-land data. In contrast, a volume of 3.0 km3 is obtained if the marine data are considered (Wiesner et al. 1995; Wiesner and Wang 1996). Moreover, Wiesner et al. (1995) and Carey (1997) demonstrated that deposition of distal tephra-fall layers in deep-sea sediments is dominantly controlled by diffuse vertical gravity currents. This process greatly reduces the residence time of fine ash in the ocean and diminishes the role of ocean currents in influencing the distribution patterns of individual layers. As a result, deep-sea ash layers can be used as stratigraphic markers and can be correlated with on-land deposits. However, the different Fontana Lapilli stratigraphic units defined on-land could not be distinguished in the marine cores. We expect the thickness of units A, B and C to be negligible around 300 km from the vent, but we cannot speculate on the dispersal of unit G. As a result, our volume calculation of unit D+E+F considering the marine-core data could be overestimated. For these reasons, we consider the marine-core data only for a qualitative comparison with the thinning trend derived by on-land data.

Constraint of physical eruption parameters for poorly exposed deposits

The determination of physical parameters can be very sensitive to the exposure of tephra deposits, the amount of field data available, and the techniques used (Bonadonna and Houghton 2005). As a result, eruption parameters derived from applying curve-fitting techniques to field data cannot be considered as absolute values. This is particularly true for poorly exposed deposits such as the Fontana Lapilli. Therefore a critical assessment of their uncertainty is necessary, in particular when used as input factors of numerical models or to define the maximum expected event of a given volcano (Marzocchi et al. 2004; Bonadonna 2006). The level of confidence associated with estimates of mass eruptive rate and eruption duration depends on the level of confidence for the total erupted volume and the height of the erupted column.

Our results, and those of Wehrmann et al. (2006), show that the maximum column height can be well constrained even for poorly exposed deposits, even when the location of the vent is not exactly known. In fact, the use of different techniques and different vent-location assumptions led to a variation of < 10% in the maximum column height.

In contrast, the determination of the erupted volume is very sensitive to the exposure of the deposit and the distribution of field data. In fact, the complete thinning trend of a poorly exposed deposit cannot be easily reproduced by standard curve-fitting techniques. If only proximal–medial data are available, exponential techniques are based on only one or two segments and therefore tend to underestimate the erupted volume (Bonadonna and Houghton 2005). In comparison, power-law fitting gives a better constraint. However, when tephra deposit is widely dispersed (i.e. the power-law exponent is > 2), the resulting volume strongly depends on the \(A_{{\text{dist}}}^{{{\text{1}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\text{1}} {\text{2}}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\text{2}}}} \) while in the cases of moderately dispersed eruptions (i.e. power-law exponent < 2), such as the Ruapehu 17 June 1996 subplinian eruption, the volume estimate is more sensitive to the choice of \(A_{\text{o}}^{{{\text{1}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\text{1}} {\text{2}}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\text{2}}}} \) (Bonadonna and Houghton 2005). For the Fontana Lapilli, the power-law integration results are strongly affected by the choice of \(A_{{\text{dist}}}^{{{\text{1}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\text{1}} {\text{2}}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\text{2}}}} \) but not very sensitive to the choice of \(A_{\text{o}}^{{{\text{1}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\text{1}} {\text{2}}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\text{2}}}} \). The empirical method of Sulpizio (2005) for the calculation of the position of break-in-slope of the exponential trend gives results in the same range as those obtained with the power-law technique and exponential method of Pyle (1989). However, the position of break-in-slope depends on the transition between different sedimentation regimes (i.e. turbulent, transitional and laminar) and therefore it strictly depends on column height and grain size distribution (Bonadonna et al. 1998). As a consequence, we consider it unsafe to speculate on the position of the break-in-slope on the basis of empirical analysis of a range of eruptions characterized by different column heights and grain size. The positions of breaks-in-slope on plots of log thickness versus square root of area of poorly exposed deposits are typically arbitrary and only depend on the distribution of points. As a result, it is safer to calculate the volume only using real field data, being aware that this is determining a minimum value for the eruption.

Using our on-land data, we obtained an erupted volume for the combined units D+E+F that varies by an order of magnitude between 0.6 km3 (one exponential segment) up to 5.5 km3 (power-law fit). However, our best estimate is between 2.9 and 3.8 km3 erupted over 5 ± 1 h. This volume estimate is based on a power-law fit with an integration limit \(A_{{\text{dist}}}^{{{\text{1}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\text{1}} {\text{2}}}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\text{2}}}} \) of 300–500 km, in agreement with marine-core data.

The Fontana Lapilli marine data confirm that the extrapolation of thinning as a power-law fit gives a better result than the exponential trend when only proximal-medial points are available. Furthermore, volume estimates based on exponential thinning are in good agreement with those based on power-law thinning when distal marine-core data are considered in the calculation, as was also shown by Bonadonna and Houghton (2005).

The mass eruptive rate is very sensitive to the choice of plume temperature. For basaltic magma, the high eruption temperature enhances the plume buoyancy (Sparks 1986). Therefore, applying the standard techniques valid for an eruption temperature of silicic magma can overestimate the mass eruptive rate and, consequently, underestimate the eruption duration. Using the modified version of the Wilson and Walker (1987) equation for a temperature of 1,300K (Sparks 1986), we obtain a mass eruptive rate that is < 50% of the value obtained with the standard model, and an estimated eruption duration that is two to three times higher than that for a cooler eruption plume. It is also important to remember that the equation of Wilson and Walker (1987) gives a maximum rate because it is based on the maximum column height. As a result, this methodology tends to underestimate the total duration of the eruption. However, Wehrmann et al. (2006) have shown a constant column height during deposition of units D, E and F. As a result, the mass eruptive rate must have been also constant during the main Plinian phase.

Interpretation and significance of the white layers

We investigated three possible mechanisms for the formation of the white layers in the Fontana Lapilli deposit:

-

1.

accumulation of ash from the waning phases of the main plume during breaks in the Plinian eruption,

-

2.

in situ alteration of clasts,

-

3.

introduction of material erupted from a coeval hydrothermal vent and unrelated to the main plume.

We discarded the first mechanism because there is no marked fining of the lapilli population preceding, or accompanying, the arrival of the white ash (Figs. 3 and 5). This means that sedimentation from plume remained constant testifying to a continuous and stable eruptive plume. The fact that the white layers can be correlated throughout the area of dispersal also rules out in situ alteration as a mechanism for forming the white layers. In contrast, the distribution of white ash in the deposit at the different outcrops indicates that it was introduced at very specific times during the eruption and was widely distributed across the dispersal area. Our preferred interpretation is, therefore, that the white layers record periods of coeval eruption from the main eruptive vent as well as from short-lived bursts of activity from an adjacent phreatic or hydrothermal vent. Lapilli erupted from the main vent must have fallen through the lower cloud erupted from the hydrothermal vent and have mingled with the finer-grained, hydrothermally altered clasts, leading to extensive coating of the juvenile scoria with the white ash material. Changes in the vigour of eruption from the phreatic vent would account for the relative abundance of ash-rich versus ash-poor layers and particularly the range in abundance of the white ash fraction. A good analogue to these deposits is in the medial-to-distal deposits of the 1886 Tarawera eruption, where lapilli from the Plinian vents alternate, and are mixed, with an ash-rich component derived from the hydrothermal-phreatomagmatic vents located up to 8 km southeast of the Plinian vents (Walker et al. 1984).

Conclusions

The Fontana Lapilli eruption can be divided into three main stages and occurred with no involvement of external water at the main Plinian vent. The isopach geometries are most consistent with vent migration during the eruption along a ESE-WNW fissure located outside of the Masaya caldera. For the main Plinian phase, we obtain a maximum plume height of 32 km and a mass discharge of 1.4 × 108 kg s−1. Our best estimate for the erupted volume ranges between 2.9 and 3.8 km3, which gives an eruption duration of 4–6 h.

Grain size analysis indicates that the main Plinian phase was characterized by a sustained column. We interpret the white layers as mixtures of juvenile material from the main Plinian vent with silica-rich, fine-grained ash being erupted simultaneously from an adjacent phreatic or hydrothermal vent.

Studies of basaltic Plinian eruptions must consider that all the physical parameters (column height, mass eruptive rate and eruption duration) are very sensitive to plume temperature. Application of models valid for an eruption temperature of silicic magma can overestimate the mass eruptive rate and underestimate the eruption duration.

Our results show how the maximum column height can be constrained within a 10% error even using poorly exposed deposits and when the vent location is not well constrained. The determination of erupted volume is, however, very sensitive to the exposure of the deposit, the number of field data available, and the curve-fitting technique used. For a poorly exposed deposit, estimates of erupted volume can vary up to one order of magnitude depending on the method used and the assumptions considered.

For the Fontana lapilli deposit, the use of distal marine-core data confirmed that a power-law fit better describes the thinning trend than the exponential extrapolation of only proximal and medial data.

References

Bice DC (1980) Tephra stratigraphy and physical aspects of recent volcanism near Managua, Nicaragua. PhD thesis, Univerisity of California, Berkeley, p 422

Bice DC (1985) Quaternary volcanic stratigraphy of Managua, Nicaragua: correlation and source assignment for multiple overlapping Plinian deposits. Geol Soc Amer Bull 96:553–566

Bonadonna C (2006) Probabilistic modelling of tephra dispersion. In: Mader HM, Coles SG, Connor CB, Connor LJ (eds) Statistics in volcanology. The Geological Society, London, pp 243–259

Bonadonna C, Ernst GGJ, Sparks RSJ (1998) Thickness variations and volume estimates of tephra fall deposits: the importance of particle Reynolds number. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 81:173–187

Bonadonna C, Houghton BF (2005) Total grainsize distribution and volume of tephra-fall deposits. Bull Volcanol 67:441–456

Carey SN (1997) Influence of convective sedimentation on the formation of widespread tephra fall layers in the deep sea. Geology 25:839–842

Carey SN, Sparks RSJ (1986) Quantitative models of the fallout and dispersal of tephra from volcanic eruption columns. Bull Volcanol 48:109–125

Carey R, Houghton BF, Sable JE, Wilson CJN (2007) Contrasting grain size and componentry in complex proximal deposits of the 1886 Tarawera basaltic Plinian eruption. Bull Volcanol 69:903–926

Chester DK, Dibben CJL, Duncan AM (2002) Volcanic hazard assessment in western Europe. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 115:411–435

Cioni R, Marianelli P, Santacroce R, Sbrana A (1999) Plinian and subplinian eruptions. In: Sigurdsson H, Houghton BF, McNutt S, Rymer H, Stix J (eds) Encyclopedia of volcanoes. Academic, San Diego, pp 477–494

Cioni R, Longo A, Macedonio G, Santacroce R, Sbrana A, Sulpizio R, Andronico D (2003) Assessing pyroclastic fall hazard through field data and numerical simulations: example from Vesuvius. J Geophys Res 108(B2):ECV2.1–ECV2.11

Coltelli M, Del Carlo P, Vezzoli L (1998) Discovery of a Plinian basaltic eruption of Roman age at Etna volcano, Italy. Geology 26:1095–1098

Connor CB, Hill BE, Winfrey B, Franklin NM, La Femina PC (2001) Estimation of volcanic hazards from tephra fallout. Nat Hazards Rev 2:33–42

De Rita D, Giordano G, Esposito A, Fabbri M, Rodani S (2002) Large volume phreatomagmatic ignimbrites from the Colli Albano volcano (Middle Pleistocene, Italy). J Volcanol Geotherm Res 118:77–98

Fierstein J, Hildreth W (1992) The Plinian eruptions of 1912 at Novarupta, Katmai National Park, Alaska. Bull Volcanol 54:646–684

Fierstein J, Natherson M (1992) Another look at the calculation of fallout tephra volumes. Bull Volcanol 54:156–167

Folk RL, Ward WC (1957) Brazon river bar, a study in the significance of grain-size parameters. J Sediment Petrol 27:3–27

Freda C, Gaeta M, Palladino DM, Trigila R (1997) The Villa Senni Eruption (Alban Hills, central Italy): the role of H2O and CO2 on the magma chamber evolution and on the eruptive scenario. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 78:103–120

Freundt A, Kutterolf S, Schmincke HU, Hansteen T, Wehrmann H, Perez W, Strauch W, Navarro M (2006) Volcanic hazards in Nicaragua: Past, present and future. In: Rose WI, Bluth GJS, Carr MJ, Ewert JW, Patino LC, Vallance JW (eds) Volcanic hazards in Central America. Geological Society of America, Special Paper 412, pp 141–165

Girard G, van Wyk de Vries B (2005) The Managua Graben and Las Sierras-Masaya volcanic complex (Nicaragua); pull-apart localization by an intrusive complex: results from analogue modelling. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 144:37–57

Head JW, Wilson L (1989) Basaltic pyroclastic eruptions: influence of gas-release patterns and volume fluxes on fountain structure, and the formation of cinder cones, spatter cones, rootless flows, lava ponds and lava flows. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 37:261–271

Hildreth W, Drake RE (1992) Volcano Quizapu, Chilean Andes. Bull Volcanol 54:93–125

Houghton BF, Smith RT (1993) Recycling of magmatic clasts during explosive eruptions—estimating the true juvenile content of phreatomagmatic volcanic deposits. Bull Volcanol 55:414–420

Houghton BF, Wilson CJN, Del Carlo P, Coltelli M, Sable JE, Carey R (2004) The influence of conduit processes on changes in style of basaltic Plinian eruptions: Tarawera 1886 and Etna 122b.c. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 137:1–14

Inman DL (1952) Measures for describing the size distribution of sediments. J Sediment Petrol 22:125–145

Kutterolf S, Freundt A, Perez W, Wehrmann H, Schmincke HU (2007) Late Pleistocene to Holocene temporal succession and magnitudes of highly-explosive volcanic eruptions in west-central Nicaragua. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 163:55–82

Kutterolf S, Freundt A, Perez T, Morz U, Schacht H, Wehrmann H, Schmincke HU (2008a) Pacific offshore records of Plinian arc volcanism in central America, part 1: along-arc correlations. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 9:Q02S01 doi:10.1029/2007GC001631

Kutterolf S, Freundt A, Perez T (2008b) The Pacific offshore record of Plinian arc volcanism in Central America, part 2: tephra volumes and erupted masses. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 9:Q02S02 doi:10.1029/2007GC001791

La Femina PC, Dixon TH, Strauch W (2002) Bookshelf faulting in Nicaragua. Geology 30:751–754

Marzocchi W, Sandri L, Gasparini P, Newhall C, Boschi E (2004) Quantifying probabilities of volcanic events: the example of volcanic hazard at Mount Vesuvius. J Geophys Res 109:B11201 doi:10.1029/2004JB003155

Paladio-Melosantos ML, Solidum RU, Scott WE, Quiambao RB, Umbal JV, Rodolfo KS, Tubianosa BS, Delos Reyes PJ, Ruelo HR (1996) Tephra falls of the 1991 eruptions of Mount Pinatubo. In: Newhall CG, Punongbaya RS (eds) Fire and mud: eruptions and lahars of Mount Pinatubo, Philippines. Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology, Quezon City, pp 513–535

Palladino DM, Gaeta M, Marra F (2001) A large K-foiditic hydromagmatic eruption from the early activity of the Alban Hills Volcanic District, Italy. Bull Volcanol 63:345–359

Perez W, Freundt A (2006) The youngest highly explosive basaltic eruptions from Masaya Caldera (Nicaragua): stratigraphy and hazard assessment. In: Rose WI, Bluth GJS, Carr MJ, Ewert JW, Patino LC, Vallance JW (eds) Volcanic hazards in Central America. Geological Society of America, Special Paper 412, pp 198–208

Pyle DM (1989) The thickness, volume and grainsize of tephra fall deposits. Bull Volcanol 51:1–15

Pyle DM (1990) New estimates for the volume of the Minoan eruption. In: Hardy DA (ed) Thera and the Aegean world. The Thera Foundation, London, pp 113–121

Sable JE, Houghton BF, Del Carlo P, Coltelli M (2006a) Changing conditions of magma ascent and fragmentation during the Etna 122b.c. basaltic Plinian eruption: evidence from clasts microtextures. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 158:333–354

Sable JE, Houghton BF, Wilson CJN, Carey R (2006b) Complex proximal sedimentation from Plinian plumes: the example of Tarawera 1886 basaltic Plinian eruption. Bull Volcanol 69:89–103

Sarna-Wojcicki AM, Shipley S, Waitt JR, Dzurisin D, Wood SH (1981) Areal distribution thickness, mass, volume, and grain-size of airfall ash from the six major eruptions of 1980. In: Lipman WP, Mullineaux DR (eds) Eruptions of Mount St. Helens, Washington. US Geological Survey Professional Paper Washington, Washington DC, pp 577–600

Scasso R, Corbella H, Tiberi P (1994) Sedimentological analysis of the tephra from 12–15 August 1991 eruption of Hudson Volcano. Bull Volcanol 56:121–132

Self S, Zhao J-X, Holasek RE, Torres RC, King AJ (1996) The atmospheric impact of the 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption. In: Newhall CG, Punongbaya RS (eds) Fire and mud: eruptions and lahars of Mount Pinatubo, Philippines. Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology, Quezon City, pp 1089–1115

Simkin T, Siebert L (1994) Volcanoes of the world. Geoscience Press Inc., Tucson

Sparks RSJ (1986) The dimensions and dynamics of volcanic eruption columns. Bull Volcanol 48:3–15

Sparks RSJ, Wilson L, Sigurdsson H (1981) The pyroclastic deposits of the 1875 eruption of Askja, Iceland. Philos Trans R Soc Lond 229:241–273

Sulpizio R (2005) Three empirical methods for the calculation of distal volume of tephra-fall deposits. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 145:315–336

Sulpizio R, Mele D, Dellino P, La Volpe L (2005) A complex, subplinian-type eruption from low-viscosity, phonolitic to tephri-phonolitic magma: the AD 472 (Pollena) eruption of Somma-Vesuvius, Italy. Bull Volcanol 67:743–767

Vergniolle S, Mangan M (1999) Hawaiian and Strombolian eruptions. In: Sigurdsson H, Houghton BF, McNutt S, Rymer H, Stix J (eds) Encyclopedia of volcanoes. Academic, San Diego, pp 447–462

Walker GPL (1971) Grainsize characteristics of pyroclastic deposits. J Geol 79:696–714

Walker GPL (1980) The Taupo pumice: product of the most powerful known (Ultraplinian) eruption. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 8:69–94

Walker GPL (1983) Ignimbrite types and ignimbrite problems. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 17:65–88

Walker GPL, Croasdale R (1972) Characteristics of some basaltic pyroclasts. Bull Volcanol 35:303–317

Walker GPL, Self S, Wilson L (1984) Tarawera, 1886, New Zealand—a basaltic Plinian fissure eruption. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 21:61–78

Watkins SD, Giordano G, Cas RAF, De Rita D (2002) Emplacement processes of the mafic Villa Senni Eruption Unit (VSEU) ignimbrite succession, Colli Albani volcano, Italy. J Volcanol Geotherm Res 118:173–203

Wehrmann H, Bonadonna C, Freundt A, Houghton BF, Kutterolf S (2006) Fontana Tephra: a basaltic Plinian eruption in Nicaragua. In: Rose WI, Bluth GJS, Carr MJ, Ewert JW, Patino LC, Vallance JW (eds) Volcanic hazards in Central America. Geological Society of America, Special Paper 412, pp 209–224

Wentworth CK, MacDonald GA (1953) Structures and forms of basaltic rocks in Hawaii. US Geol Surv Bull 994:1–98

Wiesner MG, Wang YW, Zheng L (1995) Fallout of volcanic ash to the deep South China Sea induced by the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo (Philippines). Geology 23:885–888

Wiesner MG, Wang Y (1996) Dispersal of the 1991 Pinatubo tephra in the South China Sea. In: Newhall CG, Punongbaya RS (eds) Fire and mud: eruptions and lahars of Mount Pinatubo, Philippines. Institute of Volcanology and Seismology, Quezon City, pp 537–543

Williams SN (1983) Plinian airfall deposits of basaltic composition. Geology 11:211–214

Wilson L, Walker GPL (1987) Explosive volcanic eruptions—VI. Ejecta dispersal in Plinian eruptions: the control of eruption conditions and atmospheric properties. Geophys J R Astron Soc 89:657–679

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the staff of the Instituto Nicaraguense de Estudios Territoriales (INETER) for their crucial support during field work and to Steffen Kutterolf for kindly providing information on marine-core data. We also thank Raffaello Cioni for the helpful comments and suggestions on the draft manuscript and the University of South Florida (USF) for the use of the Malvern PharmaVision 830 automated optical device. The manuscript benefited greatly from the constructive reviews of Andy Harris, Roberto Sulpizio and Don Swanson. This work was supported by NSF grants EAR-01-25719, EAR-03-10096, and EAR-05-37459, and by a fellowship from University of Rome La Sapienza (to Costantini). This is contribution no. 127 to Sonderforschungsbereich 574 “Volatiles and Fluids in Subduction Zones” at Kiel University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Editorial responsibility: A. Harris

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Costantini, L., Bonadonna, C., Houghton, B.F. et al. New physical characterization of the Fontana Lapilli basaltic Plinian eruption, Nicaragua. Bull Volcanol 71, 337–355 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-008-0227-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-008-0227-9