Abstract

There is general consensus that climate change has contributed to the observed decline, and extinction, of many amphibian species throughout the world. However, the mechanisms of its effects remain unclear. A laboratory study in 1980–1981 in which temperate zone amphibians that were prevented from hibernating had decreased growth rates, matured at a smaller size and had increased mortality compared with those that hibernated suggested one possible mechanism. I used data from a field study of common toads (Bufo bufo) in the UK, between 1983 and 2005, to determine whether this also occurs in the field. The results demonstrated two pathways by which global warming may cause amphibian declines. First, there was a clear relationship between a decline in the body condition of female common toads and the occurrence of warmer than average years since 1983. This was paralleled by a decline in their annual survival rates with the relationship between these two declines being highly correlated. Second, there was a significant relationship between the occurrence of mild winters and a reduction in female body size, resulting in fewer eggs being laid annually. Climate warming can, therefore, act on wild temperate zone amphibians by deleteriously affecting their physiology, during and after hibernation, causing increased female mortality rates and decreased fecundity in survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Currently there is a consensus that mean annual global temperatures have increased significantly over the last century (Easterling et al. 1997; Jones and Mann 2004; King 2005) and that over the last 20–25 years there have been, and continue to be, worldwide declines in many amphibian species and extinctions in some others (Beebee and Griffiths 2005; Blaustein and Wake 1990, 1995; Blaustein et al. 1994; Carey and Alexander 2003; Collins and Storfer 2003; Houlahan et al. 2000; Kiesecker et al. 2001; La Marca et al. 2005; Laurance 1996; Lips 1998; Pounds 2001; Pounds and Crump 1994; Stuart et al. 2004). There is less agreement about the causes of these declines (Alexander and Eischeid 2001; Collins and Storfer 2003; Kiesecker et al. 2001) though links with global warming (Carey and Alexander 2003; Pounds 2001; Pounds et al. 2006), habitat loss (Collins and Storfer 2003), pollution (Collins and Storfer 2003; Davidson 2004), increased ultra-violet irradiation (Blaustein et al. 2003) and disease (Berger et al. 1998; Garner et al. 2005; Lips et al. 2003; Pounds et al. 2006; Puschendorf 2003) have all been suggested.

There is now good evidence that some amphibian species can respond to a warmer climate, particularly mild winters/springs, by breeding earlier (Beebee 1995; Reading 1998) and that this may have consequences for body condition (Jørgensen 1986; Reading and Clarke 1995) and larval development (Reading and Clarke 1999), both of which have the potential to influence the dynamics of a population. What has not been demonstrated, however, is how the link between ‘global warming’ and amphibian declines operates (Collins and Storfer 2003) though Pounds et al. (2006) have suggested that temperatures in many highland areas are shifting towards the growth optimum for the pathogenic chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis), thereby encouraging outbreaks.

In a laboratory study Jørgensen (1986) demonstrated that female Danish common toads (Bufo bufo), fed ad libitum over the winter but prevented from hibernating, had reduced growth rates, higher annual mortality rates, and attained sexual maturity earlier and at a smaller size than those subjected to simulated hibernation. The study found that, irrespective of temperature, feeding and growth rates declined to a minimum during the 2–3 months prior to anticipated hibernation and that the degree to which these were restored to ‘normal’ levels after hibernation was dependent on the duration of hibernation. Thus, toads that live at high latitudes, or altitudes, are adversely affected by exposure to prolonged periods of ‘summer’ temperatures and a period of hibernation is essential for increased survival and for ‘maintaining health’ (Jørgensen 1986). Compared with cold winters, mild winters would, therefore, be expected to provide less favourable conditions for hibernation, both in terms of its depth (severity) and duration.

In addition, temperate zone amphibians accumulate and store energy reserves, in the form of fat bodies, which they utilise during hibernation. During cold winters the metabolic rate of hibernating amphibians will be low and their energy reserves utilised at a slower rate than during mild winters when their metabolic rate will be relatively higher. It might be predicted, therefore, that the body condition of amphibians emerging from hibernation, following a mild winter, would be lower than that following a cold one due to the increased utilisation of their stored fat reserves. In extreme cases, amphibian mortality resulting from mild winters might be predicted to be proportionately higher than after cold ones, due to the complete utilisation of stored energy reserves before the end of hibernation.

The aim of this analysis of data obtained from a long-term field study (1983–2005) of common toads (B. bufo) was to test the hypothesis that, compared to cold winters, mild winters result in reduced female toad body condition on emergence from hibernation, reduced female survival rates, and a decline in the body size of females breeding for the first time.

Materials and methods

Study site

The study population of common toads B. bufo was located in a flooded clay pit (approximately 0.34 ha) situated to the north of the Purbeck Hills in south Dorset, UK (Lat:50°39′N, Long:2°7′W). The breeding pond is surrounded by Rhododendron Rhododendron ponticum L. wood, mature deciduous woodland, wet scrub woodland dominated by birch Betula pendula Roth., B. pubescens Ehrh., mature Scots pine Pinus sylvestris L., pasture, and heathland dominated by Calluna vulgaris L. and Ulex europaeus L.

Methods

Annually, since 1983, sexually mature female and male common toads arriving to breed at the study pond have been captured and marked to denote the year of capture using a single toe clip. The snout-vent length (SVL) and body mass of each individual were measured. As very few females were captured after they had spawned, their body condition index (BCI) was based on their body mass prior to spawning and thus included the egg mass. Variation in egg mass size could potentially result in a false pattern of change in BCI over time. This potential problem was addressed by first considering females to be equivalent to males with eggs and then comparing the patterns of change in female and male BCI over time. A strong linear relationship, with a slope of one, would indicate that female BCI values could be derived from pre-spawning body mass values.

Between-year comparisons of female and male toad BCI were determined from a regression analysis of log10 body mass against log10 SVL after first pooling the data for all 23 years (1983–2005) and analysing the residuals, by year, to obtain a mean annual value for each sex. Positive values represented years in which the mean body condition of females was above average, and vice versa.

Annual female survival was estimated from Cormack–Jolly–Seber capture, mark, and recapture (CMR) models using the software MARK (White and Burnham 1999). Ten candidate models were defined and the fit of each was determined from the quasi-likelihood Akaike Information Criterion (QAICc) values. Four of the models were those pre-defined in MARK in which survivorship (φ) and capture probability (P) were either time dependent (t) or constant. In each of the remaining six models p was assumed to be time dependent with φ dependent on: (1) female BCI; (2) mean maximum daily environmental temperatures (maxT), (a) since 1st October the previous year (hibernation: maxT:Oct-breed) and (b) between 1st April and the end of September the previous year (activity period: maxT:Apr-Sept; (3) a combination of BCI and maxT; (4) φ having a linear trend over time. U-CARE (Pradel et al. 2003; Choquet et al. 2005) was used to test the goodness-of-fit of the model with time-dependent survival and recapture probability and to estimate the variance inflation factor \( (\ifmmode\expandafter\hat\else\expandafter\^\fi{c}) \) for comparing models.

The meteorological data used in this study were recorded at the Swanage weather station, situated approximately 12 km from the study pond. MINITAB 14 was used for all statistical analyses not directly related to the CMR analysis using MARK.

Results

Adult toads, in common with many temperate amphibian species, are only found in large numbers during their breeding season (February/March), and therefore measurements of their BCI, and estimates of their survival rates, can only be determined annually from data collected at the breeding sites. As a consequence they are the result of the conditions experienced by the toads during at least the previous year. Analysis of daily weather data recorded at the nearby Swanage weather station (south Dorset, UK) showed that, over the 23 years since 1982, there have been significant increases of 0.8 and 1.5°C, respectively, in the mean minimum and mean maximum annual temperatures (Fig. 1). Over the same period there was also a significant increase in mean maximum temperatures of the toad hibernation months (maxT:Oct-breed=4.73+0.0645 year; R 2=24.9%; P=0.015; n=23) showing that the observed rise in annual temperatures was not just the result of warmer springs/summers (maxT:Apr-Sept=12.4+0.0537 year; R 2=27.0%; P=0.011; n=23).

Change in the mean maximum, mean and mean minimum temperatures (°C) between the 1st April each year and the start of the common toad breeding season the following year (1982–2004). Regression analysis: mean max. temperature = 8.18+0.068 year (R 2=36.6%; P=0.002; n=23). mean temperature =6.67+0.052 year (R 2=29.0%; P=0.008; n=23). mean minimum temperature = 5.18+0.036 year (R 2=17.2%; P=0.049; n=23). The start of the toad breeding season was the date when toads first arrived at their breeding pond in large numbers

The patterns of change in female and male BCI over time were very similar (Fig. 2). A regression analysis of female BCI against male BCI gave a slope of approximately one and an intercept close to zero (female BCI =−0.0076+0.9604 male BCI; F 1,22=276.20; R 2=92.9%; P<0.0001) indicating that pre-spawning female body mass could be used to estimate a realistic value for female BCI.

The female recapture data (1983–2005) were over-dispersed (χ 257 =125.07, P<0.0001, \( \ifmmode\expandafter\hat\else\expandafter\^\fi{c} = 2.19 \)) with two of the four component tests used in its estimation being significant (TEST3.SR and TEST2.CT) and therefore providing possible evidence for the presence of both transients and trap dependence TEST3.SR, χ 222 =58.82, P<0.0001; TEST3.SM, χ 216 =2.15, P=0.99; TEST2.CT, χ 214 =62.69, P<0.0001; TEST2.CL, χ 25 =1.40, P=0.92. However, the results of TEST3.SR and TEST2.CT do not preclude the subsequent data analysis (Schmidt et al. 2002) and should both be treated with caution, as they were based on sparse data, i.e., from a total of 3,178 capture histories, just 453 females were captured more than once and of these only 44 (9.7%) were not captured in consecutive years.

The QAICc weight values derived for each of the models showed that the model with female BCI as a covariate fitted the data best (Table 1), with the next best two models, including a combination of BCI and temperature (maxT:Apr-Sept or maxT:Oct-Breed) as covariates, fitting the data moderately well whilst the remaining seven models were a poor fit to the data. In addition, the fit of the models with either maxT:Apr-Sept or maxT:Oct-Breed alone as the covariate indicated that the effect of temperature on female survival was relatively small, compared with that of female BCI, whilst its correlation with female BCI was relatively high, as shown by comparing the slopes of the models based on BCI and maxT (Table 2). The inclusion of maxT, with BCI, had very little effect on the slope when BCI was the only covariate. BCI emerges as the most important covariate irrespective of the effects due to temperature.

Estimated female survival was plotted against maxT:Apr-Sept and maxT:Oct-Breed together with fitted survival values for a range of maxT values (15–19 and 8–13°C, respectively, in steps of 0.01°C) from the logistic regression models. The correlation between the observed and fitted values (maxT:Apr-Sept: r=0.485, P=0.016, df=21; maxT:Oct-Breed: r=0.330, P=0.062, df=21) showed that the models accounted for 23.5 and 10.9%, respectively, of the annual variation in survival estimates. These results suggest that although the effect of temperature on female survival is mainly indirect, via its effect on BCI, the temperatures during the spring and summer months also have a significant but weak direct effect.

A significant negative relationship was found between the female BCI and the mean maximum temperature since April 1st the previous year (Fig. 3). This decline was most marked during the late 1980s. In addition, a causal relationship between temperature and BCI is suggested because the plotted data are non-sequential over time (see data labels). Significant relationships between female BCI and the mean maximum temperature of the spring/summer months (BCI=0.395–0.0224 maxT:Apr-Sept): R 2=21.4%; P=0.026; n=23) and the hibernation months (BCI=0.186–0.017 maxT:Oct-breed): R 2=19.2%; P=0.036; n=23) were also found though they each explained less of the observed variation than the temperatures occurring between Aprilyr t and breedingyr t+1.

Relationship between unspawned female toad BCI and the mean maximum temperature (°C) since 1st April the previous year (1982–2005). Regression analysis: unspawned body condition =0.350−0.0239 mean max. temperature (R 2=28.8%; P=0.008; n=23). Years (when body condition was measured) are shown against each data point

Between 1983 and 2005 annual female survival and female BCI both declined over time (Fig. 4) with the two declines being steepest between 1983 and 1991 before levelling off between 1994 and 2005. A regression analysis of survival against BCI and year (survival =0.169+3.19 BCI +0.00069 year; P<0.0001; R 2=67.2%; n=23) showed that after allowing for the effect of year the effect of BCI on female survival was highly significant (P<0.003) whilst there was no apparent effect of year after allowing for the effect of BCI (P=0.89). Thus, the annual differences in female survival are accounted for by the annual differences in female BCI. A plot of female survival estimates against BCI, together with fitted survival values obtained for a range of BCI values (−0.04 to 0.08 in steps of 0.001) from the logistic regression model [φ(BCI), p(t): Table 1] is shown in Fig. 5. The correlation between the observed and fitted values (r=0.83) show that the model accounted for 68% of the annual variation in the survival estimates.

Linear regression analysis of the mean SVL of first time breeding females against year showed an overall significant, but erratic, decline (female SVL =591−0.255 year; R 2=32.2%; P=0.005; n=23) between 1983 (mean SVL =88.2 mm, SE=0.79 mm, n=65) and 2005 (mean SVL =76.2 mm, SE =0.83 mm, n=56). Although no significant relationship (R 2=16.0%; P=0.059; n=23) was found between the mean SVL of first time breeding females and the mean maximum temperature of the winter immediately preceding first breeding, one was found with the winter preceding that (mean female SVL t =99.6−1.50 mean max. temperaturet−2; R 2=20.9%; P=0.032; n=22). The significance of this relationship was enhanced by the non-sequential nature of the data over time where that for the largest and smallest females spanned the periods 1984–1998 and 1990–2005, respectively.

Discussion

These results, based on field observations, suggest that with increasing climatic temperatures the BCI of female common toads declines, both as a result of a reduced ability to assimilate energy reserves during the spring and summer months and an increased depletion rate of stored energy reserves during mild winters compared with cold ones. The observed decline, over 23 years, in the BCI and survival rates of females arriving at their breeding pond in the early spring were predicted if the results of a laboratory study of Danish common toads also applied to wild common toads (Jørgensen 1986). The increased mortality, coupled with decreased BCI provides strong evidence that the energy reserves accumulated prior to hibernation were insufficient for many females to survive hibernation during a succession of mild winters that have occurred in the UK since 1988. The results suggest that those females that died may have done so because their accumulated energy reserves (BCI), on entering hibernation, were not sufficiently high to sustain them whilst those that survived emerged from hibernation in poor condition.

The relatively weak, but nevertheless significant, correlation between the temperature of the toad activity period (maxT:Apr-Sept) and female survival suggests that temperature may affect either the availability of prey or the ability of toads to feed, thereby impacting on their ability to assimilate body mass. However, a detailed analysis of the effects of winter temperatures on either female BCI or survival rates was not possible in the absence of data on female BCI and female numbers at the start of the hibernation period.

The weak, but significant, relationship between the SVL of first time breeding females and the mean maximum temperature of the winter 2 years prior to breeding was not surprising given the predictions resulting from the Danish laboratory study of common toads (Jørgensen 1986). This study showed that once a female has gained sexual maturity, as a result of a mild winter, then the following year (April–September) would be required for the ovaries to mature and develop eggs, enabling spawning to occur after one further winter/hibernation. The reduction in the SVL of first time breeding females in the present study are similar to the results obtained by Jørgensen (1986), which showed that mild winters reduce subsequent feeding and growth rates resulting in females reaching sexual maturity at smaller sizes.

The reduction in the SVL of breeding females may also have implications for the survival of amphibian populations through its effect on the number of eggs laid. Fecundity in toads is positively correlated with female size (Reading 1986) and thus mild winters may result, not only in decreased female survival, but also in reduced egg production. Although these combined effects may impact on recruitment to the population, there is evidence that fecundity may not be as important to population survival as mortality during post-metamorphic stages (Biek et al. 2002; Hels and Nachman 2002; Vonesh and De la Cruz 2002).

Although this study shows how climate warming is linked to survival in a temperate amphibian, it may also have important implications for neotropical amphibians living at altitude (>1,000 m), where the climate is effectively temperate and where many of the reported declines have occurred (La Marca et al. 2005). One reported cause of these declines is the chytrid fungus, B. dendrobatidis (Lips et al. 2005), that is now also present in five European countries, including the UK, and is responsible for amphibian declines in Spain and Switzerland (Garner et al. 2005). Scherer et al. (2005) also found strong evidence that drastic declines of two populations of boreal toads (Bufo boreas) in the USA were not the result of changes in weather conditions, but were due to B. dendrobatidis. However, the link between outbreaks of B. dendrobatidis and climate change appear to be strong (Pounds et al. 2006) and the susceptibility of amphibians to pathogens, such as B. dendrobatidis, is likely to increase under increasing physiological stress, such as that resulting from reduced body condition brought about by changes in climate. Evidence of an indirect effect of environmental temperature on amphibian survival, via its effect on BCI, may therefore provide one explanation for the observed increase in amphibian declines at many highland localities resulting from outbreaks of B. dendrobatidis (Pounds et al. 2006).

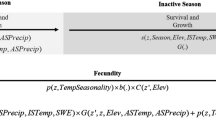

The results of this study of a wild population of common toads support those found experimentally by Jørgensen (1986). They provide field evidence that increased annual temperatures in southern England, over the 23 years between 1983 and 2005, have resulted in a decline in the body condition of female common toads (B. bufo) and that this is directly linked to an equivalent decline in their annual survivorship. They also suggest that the effect of ‘partial’ hibernation on female toad physiology, resulting from mild winters, may be an important factor linking the observed decreases in both body condition and survival rates. This study has provided one possible explanation of the links (summarised in Fig. 6) between global warming and the observed decline in some amphibian species worldwide (Beebee and Griffiths 2005; Blaustein and Wake 1990, 1995; Blaustein et al. 1994; Carey and Alexander 2003; Collins and Storfer 2003; Kiesecker et al. 2001; La Marca et al. 2005; Laurance 1996; Lips 1998; Pounds 2001; Pounds and Crump 1994; Pounds et al. 2006; Stuart et al. 2004).

References

Alexander MA, Eischeid JK (2001) Climate variability in regions of amphibian declines. Conserv Biol 15:930–942

Beebee TJC (1995) Amphibian breeding and climate. Nature 374:219–220

Beebee TJC, Griffiths RA (2005) The amphibian decline crisis: a watershed for conservation biology? Biol Conserv 125:271–285

Berger L, Speare R, Daszak P, Green DE, Cunningham AA, Slocombe R, Goggin CL, Hyatt AD, MacDonald KR, Hines HB, Lips KR, Marantelli G, Parkes HH (1998) Chytridiomycosis causes amphibian mortality associated with population declines in the rainforests of Australia and Central America. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:9031–9036

Biek R, Funk WC, Maxell BA, Mills LS (2002) What is missing in amphibian decline research: insights from ecological sensitivity analysis. Conserv Biol 16:728–734

Blaustein R, Wake DB (1990) Declining amphibian populations: a global phenomenon? Trends Ecol Evol 5:203–204

Blaustein AR, Wake DB (1995) The puzzle of declining amphibian populations. Sci Am 272:56–61

Blaustein AR, Wake DB, Sousa WP (1994) Amphibian declines: judging stability, persistence, and susceptibility of populations to local and global extinctions. Conserv Biol 8:60–71

Blaustein AR, Romansic JM, Kiesecker JM (2003) Ultraviolet radiation, toxic chemicals and amphibian population declines. Divers Distrib 9:123–140

Carey C, Alexander MA (2003) Climate change and amphibian declines: is there a link? Divers Distrib 9:111–121

Choquet R, Reboulet AM, Lebreton JD, Gimenez O, Pradel R (2005) U-CARE 2.2 user’s manual. CEFE, Montpellier, France (http://www.ftp.cefe.cnrs.fr/biom/Soft-CR/)

Collins JP, Storfer A (2003) Global amphibian declines: sorting the hypotheses. Divers Distrib 9:89–98

Davidson C (2004) Declining downwind: amphibian population declines in California and historical pesticide use. Ecol Appl 14:1892–1902

Easterling DR, Horton B, Jones PD, Peterson TC, Karl TR, Parker DE, Salinger MJ, Razuvayev V, Plummer N, Jamason P, Folland CK (1997) Maximum and minimum temperature trends for the globe. Science 277:364–367

Garner TWJ, Walker S, Bosch J, Hyatt AD, Cunningham AA, Fisher MC (2005) Chytrid fungus in Europe. Emerg Infect Dis 11:1639–1640

Hels T, Nachman G (2002) Simulating viability of a spadefoot toad Pelobates fuscus metapopulation in a landscape fragmented by a road. Ecography 25:730–744

Houlahan JE, Findley CS, Schmidt BR, Meyer AH, Kuzmin SL (2000) Quantitative evidence for global amphibian population declines. Nature 404:752–755

Jones PD, Mann ME (2004) Climate over past millennia. Rev Geophys 42:1–42

Jørgensen CB (1986) External and internal control of patterns of feeding, growth and gonadal function in a temperate zone anuran, the toad Bufo bufo. J Zool 210:211–241

Kiesecker JM, Blaustein AR, Belden LK (2001) Complex causes of amphibian declines. Nature 410:681–683

King D (2005) Climate change: the science and the policy. J Appl Ecol 42:779–783

La Marca E, Lips KR, Lötters S, Puschendorf R, Ibáñez R, Rueda-Almonacid JV, Schulte R, Marty C, Castro F, Manzanilla-Puppo J, García-Pérez JE, Bolaños F, Chaves G, Pounds JA, Toral E, Young BE (2005) Catastrophic population declines and extinctions in neotropical Harlequin frogs (Bufonidae: Atelopus). Biotropica 37:190–201

Laurance WF (1996) Catastrophic declines of Australian rainforest frogs: is unusual weather responsible? Biol Conserv 77:203–212

Lebreton JD, Burnham KP, Clobert J, Anderson DR (1992) Modelling survival and testing hypotheses using marked animals: a unified approach with case studies. Ecol Monogr 62:67–118

Lips KR (1998) Decline of a tropical montane amphibian fauna. Conserv Biol 12:106–117

Lips KR, Green DE, Papendick R (2003) Chytridiomycosis in wild frogs from southern Costa Rica. J Herpetol 37:215–218

Lips KR, Burrowes PA, Mendelson JR, Parra-Olea G (2005) Amphibian population declines in Latin America: A synthesis. Biotropica 37:222–226

Pounds JA (2001) Climate and amphibian declines. Nature 410:639–640

Pounds JA, Crump ML (1994) Amphibian declines and climate disturbance: the case of the golden toad and the harlequin frog. Conserv Biol 8:72–85

Pounds JA, Bustamante MR, Coloma LA, Consuegra JA, Fogden MPL, Foster PN, La Marca E, Masters KL, Merino-Viteri A, Puschendorf R, Ron SR, Sánches-Azofeifa GA, Still CJ, Young BE (2006) Widespread amphibian extinctions from epidemic disease driven by global warming. Nature 439:161–167

Pradel R, Wintrebert CMA, Gimenez O (2003) A proposal for a goodness-of-fit test to the Arnason-Schwarz multisite capture-recapture model. Biometrics 59:43–53

Puschendorf R (2003) Atelopus varius (harlequin frog). Fungal infection. Herpetol Rev 34:355

Reading CJ (1986) Egg production in the common toad, Bufo bufo. J Zool 208:99–107

Reading CJ (1998) The effect of winter temperatures on the timing of breeding activity in the common toad Bufo bufo. Oecologia 117:469–475

Reading CJ, Clarke RT (1995) The effects of density, rainfall and environmental temperature on body condition and fecundity in the common toad, Bufo bufo. Oecologia 102:453–459

Reading CJ, Clarke RT (1999) Impacts of climate and density on the duration of the tadpole stage of the common toad Bufo bufo. Oecologia 121:310–315

Scherer RD, Muths E, Noon BR, Corn PS (2005) An evaluation of weather and disease as causes of decline in two populations of boreal toads. Ecol Appl 15:2150–2160

Schmidt BR, Schaub M, Anholt BR (2002) Why you should use capture-recapture methods when estimating survival and breeding probabilities: on bias, temporary emigration, over dispersion, and common toads. Amphib Reptil 23:375–388

Stuart SN, Chanson JS, Cox NA, Young BE, Rodrigues ASL, Fischman DL, Waller RW (2004) Status and trends of amphibian declines and extinctions worldwide. Science 306:1783–1786

Vonesh JR, De la Cruz O (2002) Complex life cycles and density dependence: assessing the contribution of egg mortality to amphibian declines. Oecologia 133:325–333

White GC, Burnham KP (1999) Program MARK: survival estimation from populations of marked animals. Bird Study 46:120–138

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank an anonymous referee for detailed and constructive suggestions regarding the CMR analysis using MARK, and P. Rothery for assistance with the statistical analysis. I also wish to thank K. Moore who recorded the daily meteorological data for the Swanage area and the staff of the Swanage Tourist Information Centre for allowing me access to the weather data. The permanent marking of toads was licensed under the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Anssi Laurila.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reading, C.J. Linking global warming to amphibian declines through its effects on female body condition and survivorship. Oecologia 151, 125–131 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-006-0558-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-006-0558-1