Abstract

We compared prefledging growth, energy expenditure, and time budgets in the arctic-breeding red knot (Calidris canutus) to those in temperate shorebirds, to investigate how arctic chicks achieve a high growth rate despite energetic difficulties associated with precocial development in a cold climate. Growth rate of knot chicks was very high compared to other, mainly temperate, shorebirds of their size, but strongly correlated with weather-induced and seasonal variation in availability of invertebrate prey. Red knot chicks sought less parental brooding and foraged more at the same mass and temperature than chicks of three temperate shorebird species studied in The Netherlands. Fast growth and high muscular activity in the cold tundra environment led to high energy expenditure, as measured using doubly labelled water: total metabolised energy over the 18-day prefledging period was 89% above an allometric prediction, and among the highest values reported for birds. A comparative simulation model based on our observations and data for temperate shorebird chicks showed that several factors combine to enable red knots to meet these high energy requirements: (1) the greater cold-hardiness of red knot chicks increases time available for foraging; (2) their fast growth further shortens the period in which chicks depend on brooding; and (3) the 24-h daylight increases potential foraging time, though knots apparently did not make full use of this. These mechanisms buffer the loss of foraging time due to increased need for brooding at arctic temperatures, but not enough to satisfy the high energy requirements without invoking (4) a higher foraging intake rate as an explanation. Since surface-active arthropods were not more abundant in our arctic study site than in a temperate grassland, this may be due to easier detection or capture of prey in the tundra. The model also suggested that the cold-hardiness of red knot chicks is critical in allowing them sufficient feeding time during the first week of life. Chicks hatched just after the peak of prey abundance in mid-July, but their food requirements were maximal at older ages, when arthropods were already declining. Snow cover early in the season prevented a better temporal match between chick energy requirements and food availability, and this may enforce selection for rapid growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Compared to temperate and tropical environments, arctic regions present two main problems to warm-blooded animals: the cold climate imposes high thermoregulatory costs, which must be matched by food intake, and a short period of increased food availability sets a narrow window for reproduction in many species (e.g. Chernov 1985; Carey 1986). The selective force thus exerted on arctic animals includes morphological, physiological and behavioural characteristics. With respect to reproduction, developmental mode and growth rate of offspring are traits likely to be affected by this selection, as they affect both time and amount of energy required.

Many species of shorebirds (Charadrii), especially within the Scolopacidae (sandpipers, snipes and allies), breed in the boreal and arctic climate zones (Piersma et al. 1996). They have precocial young that forage for themselves from hatching onwards, leading to high muscular activity and prolonged exposure to outdoor conditions. This ontogenetic mode should lead to a high energy expenditure (Schekkerman and Visser 2001), especially in the cold and shelter-poor arctic tundra (Norton 1973). Thus, arctic shorebird chicks may need more food to achieve growth than young birds at temperate latitudes and also more than parent-fed chicks in the Arctic. At the same time, small shorebird chicks are not yet homeothermic at low ambient temperatures (Chappell 1980; Beintema and Visser 1989a; Visser and Ricklefs 1993; Visser 1998), hence a cold climate increases their need for parental brooding, and shortens potential feeding time. At first sight therefore, self-feeding precociality seems to be a mode of development not agreeing well with the arctic environment. Nevertheless, shorebirds constitute a large proportion of arctic tundra bird communities (Chernov 1985; Boertmann et al. 1991; Troy 1996), and arctic species show the highest growth rates among shorebirds (Beintema and Visser 1989a; Schekkerman et al. 1998a, 1998b), so the thermal difficulties must be offset in some way. It has been suggested that compared to lower latitudes, insect food is more abundant in the arctic summer (e.g. Lack 1968; Salomonsen 1972; Andreev 1999), while the continuous summer daylight provides extra feeding time (Karplus 1952; Lack 1954). To make full use of this, chicks could have developed thermal adaptations to reduce the need for brooding at low temperatures (e.g. Koskimies and Lahti 1964; Chappell 1980). To date, no study has evaluated these hypotheses in an integrated way.

We studied prefledging energy expenditure and time budgets of red knot Calidris canutus chicks in the Siberian Arctic, to test whether they are indeed energetically expensive. The red knot is one of the most northerly breeding shorebirds, confined to arctic tundra and polar desert (Piersma and Davidson 1992; Tomkovich and Soloviev 1996), yet shows one of the fastest growth rates found in this group. We compare energy expenditure and time budgets of knot chicks and the abundance of their invertebrate prey with those of temperate shorebirds in grasslands in The Netherlands (Schekkerman 1997; Schekkerman and Visser 2001), and use a simulation model based on the comparative data to evaluate the three hypothetical mechanisms for enabling red knots to grow so fast despite the energetic challenge posed by their environment.

Materials and methods

Study area

We studied breeding red knots at Cape Sterlegov on the Taimyr Peninsula, Siberia (75°25′N, 89°08′E) from 10 June to 12 August 1994 (Tulp et al. 1998). The study area consisted of 12 km2 of arctic tundra (sensu Chernov 1985) bordering the Kara Sea, between 0 and 50 m a.s.l. Vegetation was dominated by mosses and lichens with a considerable proportion of bare ground in the form of clay medallions or 'frost boils', and with a denser cover of grasses and sedges in moister parts. Some scattered stone ridges and rocky outcrops were present. Several small marshes and streams drained the area.

Red knot growth and behaviour

Fourteen Red knot nests and 25 broods were found by flushing incubating birds from underfoot or by rope-dragging, and by traversing the study area intensively after hatching started. Any chicks encountered were ringed, and most accompanying adults (males) were trapped and individually colour-ringed. Two adult males, one captured on the nest and the other on 1-day-old chicks, were fitted with a radio transmitter (Holohil, Canada, type BD-2, 1.8 g) glued to feather bases on the lower back (Warnock and Warnock 1993). The transmitters were used to relocate broods for doubly labelled water experiments (see below) and behavioural observations. One tagged male lost its chicks to predators after a week, but the other fledged two young.

Throughout the prefledging period, chicks were recaptured whenever possible to record their growth (103 recaptures of 37 chicks from 13 broods). Weights were determined with spring balances, accurate to 0.1–1 g. Body mass growth was described by a logistic curve. Because the exact age of many chicks was unknown as they had already left the nest when first encountered, the logistic growth rate parameter was estimated from mass increments of chicks captured at least twice (Schoener and Schoener 1978; Ricklefs 1983), using non-linear regression. Hatchling mass was measured in the field, and the asymptote was fixed at 120 g, the mean mass of first-year red knots wintering in West Africa (Wymenga et al. 1992).

To analyse environmental effects on growth rate, mass increments were used of chicks at least a day old and captured twice at intervals of 1−5 days (mean 1.7 days, SD=1.23, n=87). To make growth rates at different ages comparable, observed mass increments were divided by those predicted from the logistic equation at the given starting mass and recapture interval. These indices were regressed on average temperature and food availability during the interval. By treating chick and brood as random variables in linear mixed models (Byrk and Raudenbusch 1992), we took into account that the data represent three nested error levels (multiple observations on several chicks from the same brood). The program MLN (Institute of Education 1995) was used for model fitting. To avoid bias due to possible effects of doubly labelled water trials on growth rate, mass increments during such measurements were excluded.

Time budget observations were made on three different broods for a total of 62.6 h, covering all hours of the day and chick ages 0–13 days. Observations were made from 100–300 m distance, using a telescope. Behaviour of the male and chicks was recorded every minute, distinguishing between brooding, foraging, and other behaviours (including rest, preening, walking, and alarm). Broods formed the recording unit, as the alternation between brooding and foraging was highly synchronised among broodmates. The dependence of the proportion of time that chicks were brooded on chick age and temperature was analysed by logistic regression. Observations lasting longer than 3 h were divided into sampling units of 1.5–3 (mean 2.3) h, to standardise lengths and get an appropriate mean value for temperature, which often changed significantly over a few hours.

Energy expenditure

Measurements of daily energy expenditure (DEE, kJ/day) of free-living chicks were made using the doubly labelled water (DLW) method (Lifson and McClintock 1966; Speakman 1997). Captured chicks were injected subcutaneously in the ventral region with 0.15–0.50 ml of DLW consisting of 32% D2O and 68% H2 18O. They were kept warm in a bag or box for an equilibration period of 0.75–1 h and structural measurements and weight were recorded. Four to six 10–15 μl blood samples were then collected from veins in the leg or wing, into glass capillary tubes, which were flame-sealed within minutes. Chicks were released into the field and recaptured after 19.0–25.6 h (mean 23.3 h, SD=1.5, n=15) when a second set of blood samples and measurements was taken. In three chicks, additional blood samples were collected before injection with DLW to measure background isotope levels. Since broods roamed widely over the tundra and were often difficult to relocate, most DLW measurements were taken on chicks of the radio-tagged males. A few measurements were made on chicks of non-tagged males. At most three measurements were taken on (2) individual chicks, separated by 3- to 6-day intervals.

2H/1H and 18O/16O ratios in the blood samples were analysed with a SIRA 9 isotope ratio mass spectrometer at the Center for Isotope Research, Groningen, following procedures described in Visser and Schekkerman (1999). Analyses were done in duplicate, and a third capillary was analysed if the two measurements differed by more than 2%. Background concentrations were 0.0143 atom-% for 2H and 0.1989 atom-% for 18O (n=3). We calculated CO2-production according to Eq. 34 in Lifson and McClintock (1966), with fractionation factors for 18O and 2H taken from Speakman (1997), and a value of 0.13 for the fraction of water loss occurring by evaporation:

where N is the size of the body water pool (mol), and k o and k d the fractional turnover rates of 18O and 2H, respectively, as calculated from the isotope measurements. In a validation study on chicks of two related shorebirds, black-tailed godwit Limosa limosa and northern lapwing Vanellus vanellus, this method gave an average error of 0% (Visser and Schekkerman 1999). The errors (range −13% to +16%) were unrelated to growth rate, indicating that the method is accurate in chicks growing as fast as 20%/day. Because some DLW was occasionally lost by leakage during injection, N was not estimated from isotope dilution but from the relation between percentage water content and the fraction of adult mass attained, based on analysis of carcasses of lapwing and godwit chicks (Schekkerman and Visser 2001). DEE was calculated from rCO2 using an energy equivalent of 27.33 kJ/l CO2 (Gessaman and Nagy 1988).

Total daily metabolised energy (ME) was calculated by adding energy deposited into new tissue (E tis) to DEE in case the animal gained weight over the measurement period, and set equal to DEE if no weight gain occurred. E tis was estimated as the increment of the product of body mass and energy density. The latter was taken as ED (kJ/g)=4.38+3.21 M/M ad (M=chick body mass, g, M ad=adult mass, 120 g), based on carcass analysis of chicks of northern lapwing and black-tailed godwit (Schekkerman and Visser 2001). Dependence of DEE and ME on body mass, growth rate and weather was analysed by fitting linear mixed models, containing chick and brood as random variables, to the log-transformed data.

Weather and arthropod abundance

Three-hourly observations of air temperature (T a,°C), wind speed and cloud cover were obtained from a weather station 7 km from our study site. From 3 July onwards, operative temperature (T e,°C) was automatically recorded every 5 minutes, using a blackened copper sphere (Ø 4 cm) placed 10 cm above the ground. T e integrates air temperature and solar radiation (but not the cooling effect of wind) and provides a better description of the thermal environment than air temperature alone (Walsberg and Weathers 1986). Daily means of T e were linearly related to mean T a at the weather station: T e=1.23T a+1.96 (R 2=0.82, F 1,34=156.6, P<0.001). Occurrence of rain and snowfall was recorded daily.

Abundance of surface-active arthropods which constitute the food of red knot chicks was measured in five modified pitfall traps placed at 20 m intervals in moderately dry nanopolygonal tundra (i.e. the habitat where most of the broods were encountered). Traps consisted of white plastic jars (Ø 10 cm, 13.5 cm deep), filled with 1–2 cm of water and a drop of detergent to break the surface tension. Two crossed mesh screens of 40×50 cm, topped with a plastic funnel opening into a transparent jar, were placed over the pitfalls. In addition to surface-active animals, this structure caught low-flying invertebrates which hit the screens and crawled either downwards into the pitfall or upwards into the jar. Compared to ordinary pitfalls, the modified traps caught more small Chironomid midges and Linyphiid spiders but similar numbers of other groups (Tulp et al. 1998). Arthropods were collected daily between 2200 hours and 2400 hours, and preserved in 4% formalin. They were later identified to family or (sub)order (Hymenoptera, Collembola) and body length was measured (to nearest 0.5 mm if ≤5 mm; to 1 mm if larger). Dry weights were estimated from group-specific length-weight relationships (Rogers et al. 1977; Schekkerman, unpublished). Arthropod abundance data were log-transformed before analysis. Because mites (Acari) and springtails (Collembola) are too small to be important prey for chicks, they were not taken into account in most analyses.

Comparison with temperate shorebird chicks

Data on red knots (growing from 13.7 g at hatching to 108 g at fledging in 18 days) were compared with those for three temperate-breeding wader species, northern lapwing (growing from 17.5 to 142 g in 23 days), black-tailed godwit (28.6 to 201 g in 25 days) and common redshank Tringa totanus (15.6 to 109 g in 23 days), studied in grassland reserves in The Netherlands using similar methods. DLW measurements of energy expenditure of lapwing and godwit chicks were made at Baarn (52°12′N, 05°19′E) in 1993–1995 (Schekkerman and Visser 2001). Time budget observations were made from hides in 0.4–0.8 ha enclosures surrounded by a low fence which allowed the free-living adults, but not their chicks, to freely leave and enter. Observations were made in Flevoland (52°24′N, 5°40′E) in 1981 and 1984 (Beintema and Visser 1989a) and at Baarn in 1992–1995 (Schekkerman 1997), and totalled 992 h for godwits, 644 h for lapwing and 44 h for redshank (10, 10 and 2 broods respectively). Dependence of brooding percentages on chick mass or age and weather variables was analysed using logistic regression, in the same way as in red knots. T e was measured with the same equipment at Baarn as in Siberia; temperatures measured in Flevoland were converted to T e using regression models incorporating air temperature, time of day and solar radiation, based on data from Baarn.

Abundance of surface-active arthropods was measured in a grassland reserve at Baarn between 3 May and 7 June 1994 (i.e. the period in which most chicks are present), using the same type and number of modified pitfall traps as in Taimyr, and identical methods of collection, identification and analysis.

Results

Weather and arthropod availability

Upon our arrival on 11 June, the tundra was still 98% snow-covered. Average air temperature remained below 0°C until 18 June. After 19 June (90%), snow cover declined rapidly to 50% on 21 June and 10% on 26 June. Mean daily air temperature (T a±SD) was −0.7±3.1°C (range −4.9–4.4) in the arrival period of red knots (10–22 June), 4.5±4.4°C (range 0.9–14.2) during incubation (23 June−13 July) and 0.9±1.8°C (range 0.9–7.1) during chick-rearing (14 July−10 Aug). Mean operative temperature (T e) in the latter period was 2.8±2.8°C (range 0.2–10.1), and mist, drizzle or rain occurred on many days. Daily average wind speed was mostly between 3 and 7 m/s, with peaks up to 8–10 m/s.

Diptera were the most abundant arthropod group caught in the modified pitfall traps at Cape Sterlegov (60% of total number), followed by Araneae (23%), Hymenoptera (12%) and Coleoptera (5%). Daily total number and dry mass were strongly correlated (log-transformed data, 3 July−10 August, r 34=0.95, P<0.001), and biomass was further used as an index of arthropod availability.

Regression analysis showed a strong non-linear dependence of trapped biomass (excluding mites and springtails) on operative temperature (T e: F 1,34=62.2, P<0.001; T e 2: F 1,33=41.6, P<0.001; R 2=0.65), with a steep decline at T e<4−5°C (Fig. 1). The occurrence of rain or (wet) snowfall reduced arthropod activity (if the only explanatory variable: F 1,34=60.1, P<0.001, R 2 =0.38), even when entered into the model after temperature (F 1,32=13.3, P=0.001; R 2=0.74). A negative effect of wind speed (in isolation: F 1,34=32.3, P<0.001, R 2 =0.20) was no longer significant after temperature and rain were included (F 1,31=0.37, P=0.55). Inclusion of date and date2 after Te and precipitation further improved the model (F 2,30=5.80, P=0.007; final R 2 =0.81), indicating that independently of weather there was a unimodal seasonal trend in arthropod activity. Predicted arthropod availability peaked on 11 July when weather effects were not taken into account (Fig. 1a), but on 16 July when these were included in the regression model.

The average size-density distributions of trapped arthropods were similar between Cape Sterlegov and a Dutch grassland managed as a meadowbird reserve (Fig. 2). Because arthropods ≥8 mm were more abundant in The Netherlands, mean daily trapped biomass (mean±SD: 19.0±12.0 mg.day−1. trap−1, n=29 days) was higher here than at Cape Sterlegov (11.7±13.0 mg.day−1.trap−1, n=31 days; t-test on ln-transformed data, t 58 =3.03, P=0.002). With mites and springtails included, this difference was even larger (Cape Sterlegov 11.7±13.0 mg.day−1. trap−1, Netherlands 31.7±18.2 mg.day−1.trap−1; Fig. 2).

Red knot breeding phenology and growth

Red knots were present in the study area upon our arrival (11 June), but new migrants arrived until at least 19 June. Most of the 14 nests (12 4-egg, two 3-egg clutches) found in the intensive study area were depredated by an Arctic Fox Alopex lagopus, but 11 additional broods were later found within its borders (estimated density ≤2 breeding pairs/km2), and 14 outside it. Based on direct observations, flotation of eggs and biometrics of young, eggs hatched between 14 and 28 July. The median hatching date was 17 July, corresponding to a first-egg date of 22 June (4 days laying, 20–21 days incubation). Incubation was shared between sexes but females deserted at hatching, and joined into small flocks, which disappeared 1 or 2 weeks later. Males attended the chicks alone, until a few days after fledging. Westward migration occurred in late July and early August, and most red knots, including juveniles, had left the area by 10 August.

The mean mass of hatchlings still in the nest was 13.7±0.5 g (n=8). Chicks fledged when 17–20 days old, weighing 87–114 g at last capture. Body mass growth in relation to age (t, days) was best described as M(g)=120/(1+8.23 e−0.24 t) (SE of rate parameter K L=0.03, R 2=0.93, n=103 intervals from 37 chicks in 13 broods, mass range 13−107 g). Conversion of K L to the Gompertz' growth rate parameter (Ricklefs 1983) yields K G=0.163, which is 1.9 times the value predicted for a 120 g shorebird by Beintema and Visser (1989b). Hence, red knots are very fast growing shorebirds.

The index of chick growth rate (growth observed / expected at the observed mass) was positively related to mean operative temperature during the recapture interval (likelihood ratio test, Χ2 1=16.4, P<0.001, n=87 intervals for 33 chicks in 12 broods). The relationship seemed non-linear and ln(T e) gave a slightly better fit than T e (Χ2 1=19.7, P<0.001). Adding the (negative) effect of precipitation to that of temperature further improved the model (Χ2 1=5.23, P=0.02). However, the best fit was obtained with the logarithm of mean daily arthropod biomass trapped in the pitfalls as the independent variable (Χ2 1=49.7, P<0.001; Fig. 3). This model was not improved by the inclusion of T e (Χ2 1=1.36, P=0.24) or precipitation (Χ2 1=0.44, P=0.51), whereas adding arthropod availability to a model including both ln(T e) and precipitation resulted in a highly significant improvement (Χ2 1=27.7, P<0.001). This indicates that not only weather-induced variation in arthropod availability affected growth, but also seasonal variation. One chick lost an exceptional 8 g in a day (growth index −3.2; Fig. 3); because this occurred on a cold day with very low arthropod activity, omitting this data point did not change the results.

Relationship between the growth index of red knot chicks (growth observed / predicted at observed mass) and mean daily arthropod biomass trapped during the interval between successive captures. The lowest observed growth index was −3.2; this point was shifted to −0.95 to fit into the frame. Regression equation: y = −0.311 (SE=0.194)+0.306ln(x) (SE=0.036); further statistics in text

Time budgets

Of 62.6 observation hours, red knot chicks were brooded by the parent during 39%. In chicks older than 8–9 days, brooding was observed only rarely. Of the remaining time, chicks spent 98% foraging (other behaviours slightly underestimated as preening, resting and alarm events lasting <1 min were not recorded). Brooding was thus the key determinant of feeding time for young chicks.

The time that chicks were brooded declined strongly with increasing body mass and T e (Table 1). In addition to these effects, brooding occurred most often between 2200 and 0400 hours. Wind speed had no discernible effect on brooding, nor were any interaction effects significant. Results were very similar when age was used as independent variable instead of body mass.

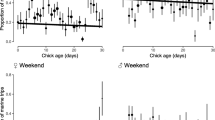

At the same mass (or age) and temperature, red knot chicks were brooded less than temperate shorebird chicks observed in The Netherlands (Fig. 4, Table 2). The difference between knot and redshank (smallest samples), was close to significance ('species' added to logistic model with mass, T e and 'night': X2 1=3.62, P=0.057); it was significant when age was used instead of mass (X2 1=4.47, P=0.035), due to the knots' faster growth. Differences with black-tailed godwit (X2 1=11.0, P<0.001) and northern lapwing (X2 1=29.9, P<0.001) were highly significant, despite the knots' smaller size.

Comparison of proportional brooding time in relation to body mass at the same temperature (A) and to operative temperature at the same age (B) for chicks of red knot (Kn), common redshank (Re), black-tailed godwit (Go), and northern lapwing (La). Lines show predictions from logistic regression models (Tables 1, 2) during dry weather in daytime

Energy expenditure

Fifteen DLW experiments were completed on 10 chicks from 5 broods. During 12 of these the chicks gained mass at an average rate of 5.3 g/day (SE=0.3), or a growth index of 0.82 (SE=0.05) compared to the average growth curve. The slower growth of DLW-injected chicks is explained by measurements being made on days with relatively low food availability: the average growth index predicted from arthropod abundance on trial days was 0.81. Three chicks lost 3.0–4.1 g/day during DLW trials (average growth index =−0.63, SE=0.13); this was more than predicted from arthropod availability (−0.06).

The power function describing daily energy expenditure (DEE, kJ/day) in relation to body mass (M, g) was: log(DEE)=0.492+1.078 log(M) (SEB0=0.163, SEB1=0.091, likelihood ratio test, Χ2 1=34,9, P<0.001; Fig. 5). Including average T e (°C) during the DLW trial improved this model: DEE decreased with increasing T e (log(DEE) = 0.442+1.129 log(M) 0.023 T e; SEB0=0.145, SEB1=0.083, SEB2=0.010, Χ2 1=4.16, P=0.041). Wind speed (P=0.75), rainfall (P=0.31), arthropod availability (P=0.92) and growth rate over the measurement interval (P=0.12) had no significant effect on DEE in addition to that of body mass.

Daily energy expenditure (DEE, kJ/day) and metabolised energy (ME, kJ/day) of red knot chicks in relation to body mass (M, g). Allometric regression equations: DEE=3.105 M 1.078; ME=6.871 M 0.916 (further statistics in text). For comparison, an allometric relationship between ME and M in birds and mammals under energy-demanding conditions (Kirkwood 1983; MEmax) is also shown

Daily metabolised energy (ME, kJ/day; DEE plus energy deposited into tissues (E tis) if the chick gained mass) was related to body mass as log(ME)=0.837+0.916 log(M) (SEB0=0.130, SEB1=0.073, Χ2 1=36.7, P<0.001; Fig. 5). In contrast to DEE, there was no significant effect of temperature on ME in addition to that of mass (Χ2 1=0.01, P=0.92); apparently the increase in DEE at low T e was compensated by reduced growth (lower E tis). Wind speed (P=0.14), rainfall (P=0.69), arthropod activity (P=0.75) or growth rate (P=0.76) did not affect ME either.

Total energy requirements of a red knot chick fledging at Cape Sterlegov were estimated by summing daily estimates of ME over the 18-day fledging period. At each age, mass predicted from the average growth curve and mean T e over the period of chicks' presence (2.8°C) were inserted into the regression equation relating DEE to mass and T e. Predicted mass and growth rate were also used to estimate E tis, which was added to DEE to obtain ME. ME increased at a decelerating rate from 65 kJ/day at hatching to 494 kJ/day at fledging (108 g). Total ME over this period amounted to 5,285 kJ, of which 14% was made up by E tis and the remaining 86% by DEE, including basal metabolism and costs of thermoregulation, activity, and biochemical synthesis.

Discussion

High energy requirements in arctic-breeding shorebirds

ME of red knot chicks exceeded an allometric prediction of 'maximum' ME based on various birds and mammals under energy-demanding conditions (Kirkwood 1983), in 14 out of 15 cases (Fig. 5). Weathers (1992) reviewed prefledging energy requirements in 30 bird species, and derived a predictive equation for total metabolised energy (TME) over the prefledging period. The largest (absolute) difference between observed and predicted values in Weathers's (1992) sample was 40%, while our value for knots is 89% above the prediction.

Two factors likely to contribute to these high energy requirements are the red knots' precocial lifestyle and the cold climate. The studies reviewed by Weathers (1992) included mostly temperate-breeding birds with parent-fed young. Self-feeding chicks exhibit high muscular activity, which should increase energy expenditure compared to parent-fed nestlings in any climate. In temperate-breeding black-tailed godwits and northern lapwings, TME was 28% and 45% higher than Weathers' (1992) prediction (Schekkerman and Visser 2001). That mass-corrected DEE was yet c. 80% higher in knots is most probably accounted for by the much lower temperature in the Arctic. The largest differences between observed and expected TME found by Weathers (1992) occurred in the arctic-breeding dunlin (+40%, Norton 1970) and arctic tern Sterna paradisaea (+35%, Klaassen et al. 1989). Subsequent measurements on American golden plover Pluvialis dominica (+52%, Visser et al., unpublished data), black-legged kittiwake Rissa tridactyla (+35%, Gabrielsen et al. 1992), little auk Alle alle (+35%, Konarzewski et al. 1993) and Wilson's storm-petrel (+148%, Obst and Nagy 1993), also revealed high TME in polar environments.

Fast growth in the Arctic, why and how?

In addition to elevating energy requirements, low temperatures increase a shorebird chick's need for parental brooding, thereby reducing time available for foraging (Chappell 1980; Beintema and Visser 1989a; Visser and Ricklefs 1993). In response, arctic-breeding shorebirds might have evolved a lower growth rate which reduces the chicks' daily energy requirements (Lack 1968; Ricklefs 1984; Klaassen et al. 1992), but in fact they show the opposite: arctic-breeding shorebirds tend to have higher growth rates than temperate species (Beintema and Visser 1989a; Schekkerman et al. 1998a; this study). An ultimate explanation for this is that the length of the season suitable for growth is short in the Arctic, constrained at the start by snow melt and at the end by declining temperature or food availability (e.g. Holmes 1966a, 1966b, 1972; Carey 1986; see below). In addition, fast growth itself may help chicks to overcome the energetic difficulties, because size is an important thermal characteristic of animals (Visser 1998). At the proximate level, the fast growth shows that there must be factors compensating for the thermal difficulties faced by arctic chicks. Below, we explore the applicability to the red knot's case of three (not mutually exclusive) mechanisms that have been proposed.

Day length

The continuous arctic summer daylight does not impose an inactive period on visual foragers, and this would allow chicks to increase their daily energy intake and hence growth rate compared to lower latitudes (Karplus 1952; Lack 1954; Kvist and Lindström 2000). Red knots, however, did not take full advantage of this: chicks were brooded more between 2200 hours and 0400 hours than during other times, irrespective of temperature. Although the sun never set until early August, light levels were noticeably lower 'at night', and activity and harvestability of arthropods may have been reduced. Alternatively, young knots may need more sleep than can be accommodated into daytime brooding bouts, and may have taken extra resting time 'at night'. Adult birds of 12 species observed in arctic summer conditions slept 3.7 h per day on average (Amlaner and Ball 1983). Compared to a 8-h dark period in spring in The Netherlands, this would still allow for a 27% increase in feeding time. Growing animals like young knots may need more sleep, but how much is unclear.

Cold-hardiness

Arctic chicks may have evolved structural or metabolic adaptations that reduce the need for parental brooding and thus increase foraging time (Chappell 1980). Indeed, red knots were brooded less than chicks of three temperate shorebird species at the same mass and temperature, and they became thermally independent earlier. This agrees with the finding that hatchlings of ducks with a northern breeding distribution are cold-hardier than those of more southern species (Koskimies and Lahti 1964). Increased cold-hardiness may be achieved in three ways: (1) arctic chicks may be better isolated, e.g. have thicker down; (2) they may tolerate lower body temperatures than temperate chicks (Norton 1973; West and Norton 1975; Chappell 1980); and (3) they may be able to elevate metabolic rate higher above basal level under cold stress. The latter two mechanisms might be facilitated by a reduced risk of infection and disease in arctic compared to temperate environments, allowing arctic chicks to compromise immunodefence for increased metabolic performance (Piersma 1997).

We cannot distinguish between these mechanisms on the basis of our data. The few literature data on operational body temperatures in shorebirds do not support hypothesis 2. Chicks of three arctic Calidris sandpipers gave distress calls and became sluggish at a core temperature of c. 30°C (Norton 1973), while chicks of the temperate common redshank voluntarily tolerated 27°C, and common snipe Gallinago gallinago cooled down to 24−26°C without signs of distress (Myhre and Steen 1979). Subtropical crowned plover Vanellus coronatus chicks also voluntarily operated at body temperatures down to 30°C (Brown and Downs 2002). Evidence for mechanisms 1 and 3 was found in young eiders Somateria mollissima (Koskimies and Lahti 1964; Steen et al. 1989). Mechanism 3 would contribute to the chicks' high energy expenditure, so that the gain in feeding time will be partly offset by a concomitant increase in energy requirements.

Food availability

Alternative to increased foraging time, energy intake rate during foraging might be higher in the summer tundra than in temperate environments (Lack 1968; MacLean and Pitelka 1971; Salomonsen 1972; Andreev 1999). Our pitfall samples revealed a lower rather than a higher mean daily biomass of surface-active arthropods at Cape Sterlegov than in a temperate meadow. Because arthropod abundance and activity may vary between years as well as between sites, this finding cannot be generalised, but red knots at Cape Sterlegov did not experience a higher abundance of food than Dutch shorebird chicks in 1994. However, they might still have achieved a higher intake rate, if prey were more easily detected or captured. This could be a result of the simpler structure of the tundra vegetation, compared to a temperate grassland sward, or of a larger proportion of slow-moving or wingless arthropods at high latitudes (cf. Chernov 1985).

Comparative simulation model

To explore the relative importance of the explanations discussed above, we constructed a comparative model in which the (metabolisable) energy intake rate during foraging, required to meet the daily demands for maintenance and growth, was simulated on the basis of our measurements of ME and foraging time, for red knots at Cape Sterlegov and for common redshank in The Netherlands. Redshank are similar in adult mass (109 g) to knot (120 g), but grow more slowly. If the simulated intake rate of knots exceeds that of redshank, better feeding conditions must be invoked to explain the fast growth of arctic knot chicks; if not the higher metabolism can be met solely by an increase in foraging time. By changing values for temperature, daylength, growth rate and cold-hardiness, we also explored which factors are most important in maximising feeding time in the Arctic. We considered that without a dark period of forced inactivity, sleep requirements may reduce foraging time unless they can be fitted within brooding bouts. Equations and assumptions of the model are detailed in the Appendix.

The model predicts potential foraging time (FT), energy requirements (ME) and required intake rate (RI) for each day during an 18-day prefledging period. Total FT over this period for a common redshank in The Netherlands was indexed at 100%. Allowing for 6 h of sleep, predicted total FT for red knots in Taimyr is very similar (102%; without sleep 128%; Fig. 6). Despite their greater cold-hardiness 0- to 4-day-old knots have less foraging time than redshank due to the low temperature; later this is reversed but the knots' advantage depends strongly on their need for sleep.

Simulated potential foraging time (FT) in relation to age (bottom panel) of red knot and common redshank chicks, and of imaginary chicks with mixed species/environment characters (see Appendix for model details). Starting with a redshank in a temperate environment (1), T e was changed from 15°C to 3°C (2), then day length from 16 to 24 h/day (3), and then growth rate (4) and finally cold-hardiness (5) to a red knot's. Horizontal broken line indicates maximum potential foraging time under the assumption of 6 h needed for sleep. Upper panel shows the resulting total foraging time over 18 days (area under curves), indexed to 100 for a temperate redshank (black: with 6 h/day sleep; grey: extra if no sleep required). Kn red knot, Re common redshank, Re* redshank with knot growth rate

If a redshank chick were to live at 3°C under a temperate daylength of 16 h, its total FT over 18 days would be reduced to 46% of that at 15°C (Fig. 6). With continuous daylight and 6 h/day of sleep at 3°C (i.e. after an imaginary translocation to the arctic), the redshank's FT would be 61% of that in The Netherlands. Assigning a knot's growth rate to this chick increases FT (to 82%), because it is larger than a redshank at each age and thus requires less brooding. Finally, the larger cold-hardiness of a knot increases FT to 102%. The effects of growth rate and cold-hardiness partly substitute each other: when a redshank chick at 3°C and an 18-h day is given knot cold-hardiness, FT increases from 61% to 95%, and increasing growth rate only adds a further 7%.

Total ME over 18 days is 160% higher in red knots than in common redshank, causing a large difference in required foraging intake rate (RI, Fig. 7). Because ME strongly depends on body mass, much of this difference is caused by the knots' higher growth rate. Assuming knot growth rate for redshank, and allowing for a coupling between growth rate and RMR elevating ME by a further 9% (see Appendix), the difference in TME reduces to 46%. This would bring RI of redshank very close to that of knots if these need no time for sleep (Fig. 7), but it is more likely that knots need a higher intake rate.

Simulated required (metabolisable) intake rate in relation to age for red knot and common redshank chicks, and of imaginary chicks with mixed species/environment characters. Lines a−d: red knots need a higher intake rate than redshank, but the difference is strongly dependent on time needed for sleep. Lines e−f: without a knot's greater cold-hardiness, young (≤5 days) chicks would need extremely high intake rates. Kn Red knot, Re common redshank, Re* redshank with knot growth rate, with allowance for coupling of growth rate and RMR (see Appendix)

We conclude from this simulation that red knot chicks can grow up successfully in the arctic because of a combination of factors. Cold-hardiness and growth rate are important factors compensating for feeding time lost due to low temperatures. Continuous daylight also contributes, but how much depends strongly on the unknown time needed for sleep. The resulting total feeding time differs little between red knots and common redshanks in their natural environment. However, because knots expend more energy, a higher foraging intake rate must still be invoked to fully explain their fast growth. Since we trapped fewer rather than more surface-active invertebrates in our arctic study area than in a temperate grassland, this seems more likely due to a greater harvestability (easier detection or capture) of invertebrates in the tundra than to a difference in abundance.

Fast growth and increased cold-hardiness, if achieved by a higher peak metabolism, contribute to the high energy requirements of red knots. Although these traits therefore have costs as well as benefits, the cold-hardiness of knots seems essential for survival during early life, when feeding time is constrained by the need for parental brooding. If translocated to the Arctic, redshank chicks up to 5–6 days old would need an excessively high intake rate, unlikely to be achieved in the field (Fig. 7). Assigning knot growth rate to such a chick shortens this critical period by a few days, but does not eliminate it. Lipid stores of neonate shorebird chicks allow for no more than c. 1 day of survival at peak metabolic rate (Visser and Ricklefs 1995). Only introducing the greater cold-hardiness of young red knots reduces RI to feasible levels throughout.

Effects of weather, food availability and breeding phenology on growth rate

Despite their high overall growth rate, red knot chicks did at times run into energetic problems, indicated by the strong relationship between growth rate and weather. Three non-exclusive mechanisms may underlie this. (1) At low temperatures young chicks were brooded more, and thus had less time available for foraging. However, weather also affected growth rate of older, thermally independent chicks. (2) DEE but not ME increased with falling temperature, indicating that on cold days energy is allocated to thermoregulation at the expense of tissue formation. (3) Low temperature and precipitation strongly reduced the activity of surface-dwelling invertebrates. Though we did not measure intake rate directly, it is likely that this represents a reduction in prey availability for chicks: on cold days invertebrates were hardly visible on the tundra surface (cf. Holmes 1966a). Our finding that trapped arthropod biomass predicted chick growth rate better than weather variables suggests that food availability was the most important factor, and was adequately described by the pitfall samples.

The strong relationship between chick growth rate and arthropod availability points to the importance of timing reproduction so that the chicks can make full use of the summer peak in insect abundance (e.g. Hurd and Pitelka 1954; Holmes 1966a, 1966b; Nettleship 1974). The median hatching date of red knots in our study fell 6 days after the observed peak date of arthropod availability, though only 1 day after the predicted seasonal maximum corrected for temperature effects. However, the simulation model showed that required intake rate is higher for chicks older than 10 days than for newly hatched young (Fig. 7), hence peaked at a time when food availability was already declining. The seasonal curve for arthropod availability dropped below 5 mg.day−1.trap−1, a level below which growth rate declined seriously, on 28 July (Fig. 1), a week before chicks born on the median hatching date fledged. Near the median fledging date, the predicted growth rate index dropped below 50%. Unless older chicks exploit additional food sources unavailable to young ones (but we did not see them, for example, probe for buried larvae), red knots might therefore increase their offspring's growth rate and survival by laying earlier. In 1994, however, they could hardly have done so, because only 10% and 50% of the tundra had become snow-free on the earliest and median laying dates respectively. Clutches can only be initiated after suitable nest sites have become exposed, and shorebird nests in small snow-free patches incur high predation risk (Byrkjedal 1980). Similar constraints on fitting laying date to the seasonal peak in food availability for the young were reported for arctic-breeding geese (Sedinger and Raveling 1986; Lepage et al. 1998; Madsen et al. 1998). Such a mismatch will contribute to selection for a strategy of maximising growth rate at the expense of high energy requirements. While this strategy may be common in arctic birds (Klaassen and Drent 1991; see Fortin et al. 2000 for another precocial example), in the small and extremely northerly breeding red knot the energetic consequences show up particularly clearly.

References

Amlaner CJ, Ball NJ (1983) A synthesis of sleep in wild birds. Behaviour 87:85–119

Andreev AV (1999) Energetics and survival of birds in extreme environments. Ostrich 70:13–22

Beintema AJ, Visser GH (1989a) The effect of weather on time budgets and development of chicks of meadow birds. Ardea 77:181–192

Beintema AJ, Visser GH (1989b) Growth parameters of charadriiform chicks. Ardea 77:169–180

Boertmann D, Meltofte H, Forchhammer M (1991) Population densities of birds in central northeast Greenland. Dan Ornithol Foren Tidsskr 85:151–160

Brown M, Downs CT (2002) Development of homeothermy in hatchling crowned plovers Vanellus coronatus. J Therm Biol 27:95–101

Byrk AS, Raudenbush SW (1992) Hierarchical linear models, application and data analysis. Sage, London.

Byrkjedal, I (1980) Nest predation in relation to snow cover a possible factor influencing the start of breeding in shorebirds. Ornis Scand 11:249–252

Carey C (1986) Avian reproduction in cold climates. Proc Int Ornithol Congr 19:2708–2715

Chappell MA (1980) Thermal energetics of chicks of arctic-breeding shorebirds. Comp Biochem Physiol 65A:311–317

Chernov YI (1985) The living tundra. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Fortin D, Gauthier G, Larochelle J (2000) Body temperature and resting behaviour of Greater Snow Goose goslings in the High Arctic. Condor 102:163–171

Gabrielsen GW, Klaassen M, Mehlum F (1992) Energetics of Black-legged Kittwake chicks. Ardea 80:29–40

Gessaman, Nagy KA (1988) Energy metabolism: errors in gas excange conversion factors. Physiol Zool 61:507–513

Holmes RT (1966a) Feeding ecology of the Red-backed Sandpiper (Calidris alpina) in Arctic Alaska. Ecology 47:32–45

Holmes RT (1966b) Breeding ecology and annual cycle adaptations of the red-backed sandpiper (Calidris alpina) in Northern Alaska. Condor 68:3–46

Holmes RT (1972) Ecological factors influencing the breeding season schedule of Western Sandpipers (Calidris mauri) in subarctic Alaska. Am Midl Nat 87:472–491

Hurd PD, Pitelka FA (1954) The role of insects in the economy of certain Arctic Alaskan birds. Proc 3rd Alaskan Sci Conf:136–137

Institute of Education (1995) MLN. Institute of Education, London

Karplus, M (1952) Bird activity in the continuous daylight of arctic summer. Ecology 33:129–134

Kirkwood JK (1983) A limit to metabolisable energy intake in mammals and birds. Comp Biochem Physiol 75A:1–3

Klaassen M, Drent RH (1991) An analysis of hatchling resting metabolism: in search of ecological correlates that explain deviations from allometric relations. Condor 93:612–629

Klaassen M, Bech C, Masman D, Slagsvold G (1989) Growth and energetics of Arctic Tern chicks (Sterna paradisaea). Auk 106:240–248

Klaassen M, Zwaan B, Heslenfeld P, Lucas P, Luijckx B (1992) Growth rate associated changes in the energy requirements of tern chicks. Ardea 80:19–28

Konarzewski M, Taylor JRE, Gabrielsen GW (1993) Chick energy requirements and adult energy expenditures of Dovekies (Alle alle). Auk 110:343–353

Koskimies,J, Lahti L (1964) Cold-hardiness of the newly hatched young in relation to ecology and distribution of ten species of European ducks. Physiol Zool 65:803–814

Kvist A, Lindström Å (2000) Maximum daily energy intake: it takes time to lift the metabolic ceiling. Physiol Biochem Zool 73:30–36

Lack D (1954) The natural regulation of animal numbers. Oxford University Press, London

Lack D (1968) Ecological adaptations for breeding in birds. Methuen, London

Lepage D, Gauthier G, Reed A. (1998) Seasonal variation in growth of Greater Snow goose goslings: the role of food supply. Oecologia 114:226–235

Lifson N, McClintock R (1966) Theory of use of the turnover rates of body water for measuring energy and material balance. J Theor Biol 12:46–74

MacLean SF, Pitelka FA (1971) Seasonal patterns of abundance of tundra arthropods near Barrow. Arctic 24:19–40

Madsen J, Bregneballe T, Frikke J, Kristensen J-B (1998) Correlates of predator abundance with snow and ice conditions and their role in determining timing of nesting and breeding success in Svalbard Light-bellied Brent Geese Branta bernicla hrota. Nor Polarinst Skr 200:221–234

Myhre K, Steen JB (1979) Body temperature and aspects of behavioural temperature regulation in some neonate subarctic and arctic birds. Ornis Scand 10:1–9

Nettleship DN (1974) The breeding of the knot Calidris canutus at Hazen Camp, Ellesmere Island, N.W.T. Polarforschung 44:8–26

Norton DW (1970) Thermal regimes of nests and bioenergetics of chick growth in the Dunlin (Calidris alpina) at Barrow, Alaska. MSc thesis, University of Alaska, Fairbanks

Norton DW (1973) Ecological energetics of calidridine sandpipers breeding in northern Alaska. PhD, thesis, University of Alaska, Fairbanks

Obst BS, Nagy KA (1993) Stomach oil and the energy budget of Wilson's Storm-petrel nestlings. Condor 95:792–805

Piersma T (1997) Do global patterns of habitat use and migration strategies co-evolve with relative investments in immunocompetence due to spatial variation in parasite pressure? Oikos 80:623–631

Piersma T, Davidson NC (eds) (1992) The migration of knots. Wader Study Group Bull 64 [Suppl]:1–209

Piersma T, van Gils J, Wiersma P (1996) Family Scolopacidae (sandpipers, snipes and phalaropes). In: del Hoyo J, Elliot A, Sargatal J (eds). Handbook of the birds of the world, vol 3. Lynx, Barcelona, pp 444–553

Ricklefs RE (1983) Avian postnatal development. In Farner DS, King JR, Parkes KC (eds). Avian biology, vol VII. Academic Press, New York, pp 1–83

Ricklefs RE (1984) The optimization of growth rate in altricial birds. Ecology 65:1602–1616

Rogers LE, Buschbom LR, Watson CR (1977) Length-weight relationships for shrubsteppe invertebrates. Ann Entomol Soc Am 70:51–53

Salomonsen F (1972) Zoogeographical and ecological problems in arctic birds. Proc Int Ornithol Congr 15:25–77

Schekkerman H (1997) Grassland managements and growth opportunities for meadowbird chicks (in Dutch). IBN-report 292, Institute of Forestry and Nature Research, Wageningen

Schekkerman H, Visser GH (2001) Prefledging energy requirements in shorebirds: energetic implications of self-feeding precocial development. Auk 118:944–957

Schekkerman H, Nehls G, Hötker H, Tomkovich PS, Kania W, Chylarecki P, Soloviev M, van Roomen M (1998a). Growth of Little Stint Calidris minuta chicks on the Taimyr Peninsula, Siberia. Bird Study 45:77–84

Schekkerman H, van Roomen M, Underhill LG (1998b) Growth, behaviour of broods and weather-related variation in breeding productivity of Curlew Sandpipers Calidris ferruginea. Ardea 86:153–186

Schoener TW, Schoener A (1978) Estimating and interpreting body mass growth in Anolis lizards. Copeia 1978:390–405

Sedinger JS, Raveling DG (1986) Timing of nesting in Canada Geese in relation to the phenology and availability of their food plants. J Anim Ecol 55:1083–1102

Speakman JR (1997) Doubly labelled water. Theory and practice. Chapman and Hall, London.

Steen JB, Grav H, Borch-Iohnsen B, Gabrielsen GW (1989) Strategies of homeothermy in Eider ducklings (Somateria mollissima). In: Bech C, Reinertsen W (eds) Physiology of cold adaptation in birds. NATO ASI Ser A, vol 173. Plenum Press, New York, pp 361–370

Tomkovich PS, Soloviev MY (1996) Distribution, migration and biometrics of knots Calidris canutus canutus on Taimyr, Siberia. Ardea 84:85–98

Troy D (1996) Population dynamics of breeding shorebirds in Arctic Alaska. Int Wader Stud 8:15–27

Tulp I, Schekkerman H, Piersma T, Jukema J, de Goeij P, van de Kam J (1998) Breeding waders at Cape Sterlegova, northern Taimyr, in 1994. WIWO-report 61. Working Group International Wetland and Waterbird Research, Zeist, The Netherlands

Visser GH (1998) Development of temperature regulation. In Starck JM, Ricklefs RE (eds). Avian growth and development. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 117–156

Visser GH, Ricklefs RE (1993) Development of temperature regulation in shorebirds. Physiol Zool 66:771–792

Visser GH, Ricklefs RE (1995) Relationship between body composition and homeothermy in neonates of precocial and semiprecocial birds. Auk 112:192–200

Visser GH, Schekkerman H (1999) Validation of the doubly labelled water method in precocial birds: the importance of assumptions concerning evaporative water loss. Physiol Biochem Zool 72:740–749

Walsberg GE, Weathers WW (1986) A simple technique for estimating operative environmental temperature. J Therm Biol 11:67–72

Warnock N, Warnock SE (1993) Attachment of radio-transmitters to sandpipers: review and methods. Wader Study Group Bull 70:28–30

Weathers WW (1992) Scaling nestling energy requirements. Ibis 134:142–153

West GC, Norton DW (1975). Metabolic adaptations of tundra birds. In: Vernberg FJ (ed) Physiological adaptation to the environment. Intext, New York pp 301–329

Wymenga E, Engelmoer E, Smit E, van Spanje TM (1992) Geographical origin and migration of waders wintering in West Africa. In: Altenburg W, Wymenga E, Zwarts L (eds.) Ornithological importance of the coastal wetlands of Guinea-Bissau. WIWO-report 26. Working Group International Wetland and Waterbird Research, Zeist, The Netherlands, pp 23–52

Acknowledgements

Petra de Goeij, Jan van de Kam and Joop Jukema provided indispensable help during fieldwork, with further assistance from Hans Dekkers and Valeri Bozun. Berthe Verstappen (CIO) skilfully performed the isotope analyses. The project was financed by the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture, Nature Management and Fisheries, Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ), Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), Stichting Plancius, Lund University, and c. 80 individual private benefactors. Logistic help was provided by the Institute of Evolutionary Morphology and Animal Ecology, Russian Academy of Sciences, staff of the Great Arctic Reserve, and by Gerard Boere, Bernard Spaans, Bart Ebbinge and Gerard Müskens. The manuscript benefited from comments by Bruno Ens, Rudi Drent, Arie Spaans, and Eric Stienen. This is NIOZ-publication 3599.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Simulation model

The simulation model predicts body mass, foraging time, energy requirements and required metabolisable energy intake of red knot and common redshank chicks during an 18-day fledging period, on the basis of growth, time budget and metabolism data reported in this paper or from the literature. We distinguished two environments differing in daylength (D, h/day) and operative temperature (T e, °C): arctic (D=24 h/day, T e=3°C, data from Cape Sterlegov) and temperate (D=16 h/day, T e=15°C, data from The Netherlands, May–June 1992–1995).

At each age t, body mass (M, g) of chicks was predicted from a logistic growth curve:

-

knot:

-

redshank:

The proportion of daylight time that chicks were brooded by a parent (B) was calculated by inserting mass and T e into logistic regression equations derived from our time budget observations (Tables 1, 2). As too few observations with rain were made for knots to estimate its effect on brooding time, we used the equations for dry weather in both species:

-

knot:

-

redshank:

Potential foraging time (FT, h/day) was calculated as day length minus brooding time. Redshank chicks do not forage during darkness (personal observation). We made calculations including and excluding the condition that chicks need 6 h of sleep each day, to show the effect of this requirement. We assumed that temperate chicks fit this into the 8-h night, while arctic chicks sleep whenever brooded and reduce foraging time only if daily brooding time is less than time required for sleep (i.e., if B<0.25):

-

arctic:

-

temperate:

In a balanced budget, total metabolisable energy intake over the hours spent foraging equals energy metabolised over the entire 24-h period (ME, kJ/day). Hence, required metabolisable energy intake rate while foraging (RI, J/s) at each age was calculated as:

ME is the sum of daily energy expenditure as measured with DLW (DEE, kJ/day) and energy incorporated into tissue (E tis, kJ/day):

E tis was calculated as the daily increment of the product of body mass and energy density, the latter estimated from the fraction of adult mass attained (see Materials and methods):

-

knot:

-

redshank:

For DEE of knot chicks, we used the equation derived in Results, inserting T e=3°C. Because DEE was not measured in common redshank, we used the mass-DEE relationship for black-tailed godwit chicks (Schekkerman and Visser 2001). This relation did not differ significantly from that for northern lapwings, despite considerable differences in age at the same mass, hence we assumed that it applies to redshank as well. The equation is based on DLW measurements made at a mean T e of 15°C.

-

knot:

-

redshank:

No predictions of ME and RI were made at ages 0−2 days, because regression equations overestimate energy requirements during this period (there is a rapid increase in metabolism over the first 3 days, Visser and Ricklefs 1993), and because the contribution of energy stores present in the hatchling (yolk) was not taken into account.

The effect of environmental and physiological variables on FT and RI was explored by exchanging environment and species parameters. For instance, a redshank chick was virtually transposed into the Arctic by changing daylength from 16 to 24 h/day and T e from 15°C to 3°C. Subsequently exchanging Eq. 4 for Eq. 3 shows the effect on foraging time of a knot's greater cold-hardiness than that of a redshank.

When comparing ME and RI between the species, the difference in growth rate must be taken into account, as ME depends strongly on body mass. We did so by inserting the red knot growth equation, (Eq. 1) into the model for common redshank. Klaassen and Drent (1991) proposed that Resting Metabolic Rate in hatchling birds is coupled to growth rate, which implies that redshank could only grow at a knot's rate at the expense of an increase in RMR. A rough estimate of this additional effect would be a 9% increase of ME (based on Fig. 4 in Klaassen and Drent 1991, a 75% higher growth rate would lead to a 29% increase in RMR which is c. 33% of ME in temperate shorebird chicks, Schekkerman and Visser 2001).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schekkerman, H., Tulp, I., Piersma, T. et al. Mechanisms promoting higher growth rate in arctic than in temperate shorebirds. Oecologia 134, 332–342 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-002-1124-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-002-1124-0