Abstract

Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) account for 40–50 % of chronic kidney disease that manifests in the first two decades of life. Thus far, 31 monogenic causes of isolated CAKUT have been described, explaining ~12 % of cases. To identify additional CAKUT-causing genes, we performed whole-exome sequencing followed by a genetic burden analysis in 26 genetically unsolved families with CAKUT. We identified two heterozygous mutations in SRGAP1 in 2 unrelated families. SRGAP1 is a small GTPase-activating protein in the SLIT2–ROBO2 signaling pathway, which is essential for development of the metanephric kidney. We then examined the pathway-derived candidate gene SLIT2 for mutations in cohort of 749 individuals with CAKUT and we identified 3 unrelated individuals with heterozygous mutations. The clinical phenotypes of individuals with mutations in SLIT2 or SRGAP1 were cystic dysplastic kidneys, unilateral renal agenesis, and duplicated collecting system. We show that SRGAP1 is expressed in early mouse nephrogenic mesenchyme and that it is coexpressed with ROBO2 in SIX2-positive nephron progenitor cells of the cap mesenchyme in developing rat kidney. We demonstrate that the newly identified mutations in SRGAP1 lead to an augmented inhibition of RAC1 in cultured human embryonic kidney cells and that the SLIT2 mutations compromise the ability of the SLIT2 ligand to inhibit cell migration. Thus, we report on two novel candidate genes for causing monogenic isolated CAKUT in humans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) account for 40–50 % of chronic kidney disease that manifests in the first two decades of life (Brakeman 2008; Smith et al. 2007). The wide range of structural malformations (e.g., unilateral renal agenesis, multicystic dysplastic kidneys, duplex collecting system, and vesicoureteral reflux) results from developmental defects of the kidneys and/or the urinary tract (Ichikawa et al. 2002; Vivante et al. 2014). More than 31 different monogenic causes of isolated CAKUT in humans have been described, which account for ~12 % of cases (Hwang et al. 2014; Vivante et al. 2014). The pathogenetic basis of CAKUT lies in the disturbance of nephrogenesis due to mutations in genes that play important roles during kidney development. The underlying molecular control of normal nephrogenesis is governed by a large number of genes and signaling pathways that orchestrate these complex events. Perturbation in any of these steps can cause CAKUT, as supported by mouse models and human disease (Rasouly and Lu 2013; Vivante et al. 2014). The metanephric kidney is formed via reciprocal interaction between the ureteric bud (UB) and the metanephric mesenchyme (MM), starting at 4 weeks of gestation in humans or on embryonic day 10.5 in mice. UB outgrowth is considered the initiating event, which critically depends on tightly regulated GDNF–RET signaling at the interface of the UB and the MM (Costantini and Shakya 2006; Durbec et al. 1996; Jeanpierre et al. 2011; Pepicelli et al. 1997; Sanchez et al. 1996; Tang et al. 1998; Vega et al. 1996). Slit2 and Robo2 are expressed as ligand and transmembrane receptor in the UB and the MM, respectively. SLIT2–ROBO2 signaling has been shown to play a role in limiting GDNF–RET signaling to the site of the ureteric budding (Grieshammer et al. 2004; Piper et al. 2000). The importance of SLIT2–ROBO2 signaling in metanephric kidney development is underlined by knockout mouse models for Slit2 and Robo2 as well as heterozygous ROBO2 mutations in humans with CAKUT (Grieshammer et al. 2004; Hwang et al. 2014; Lu et al. 2007).

In humans, most CAKUT-causing genes reported to date exhibit an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance with variable expressivity and incomplete penetrance (Gbadegesin et al. 2013; Hwang et al. 2014; McPherson et al. 1987; Sanna-Cherchi et al. 2013). Nevertheless, mutations in seven recessive CAKUT-causing genes have recently been discovered (Humbert et al. 2014; Kohl et al. 2014; Saisawat et al. 2014).

To identify additional single-gene causes of CAKUT, we conducted whole-exome sequencing (WES) followed by a burden analysis of novel heterozygous likely pathogenic variants in 26 unrelated individuals with CAKUT including their parents. Under the assumption that autosomal dominant disease causing genes harbor very few or no pathogenic variants in any healthy control cohort due to purifying natural selection, we hypothesized that likely pathogenic variants in the same gene in two or more unrelated families with CAKUT, with absence of likely pathogenic variants in the same gene from control cohorts (positive genetic burden), may indicate causality. Therefore, we compared the numbers of likely pathogenic variants per gene in our CAKUT cohort to the numbers of different but also likely pathogenic variants in 2000 Swedish control exomes. Importantly, since all considered variants were novel and, hence, absent from the control cohort, we merely compared the numbers of different, but equally pathogenic variants as previously described by Boyden et al. (2012).

We identified 29 genes as significantly enriched with potentially pathogenic variants in our group of 26 unsolved CAKUT families. Amongst them, SRGAP1 was mutated in two families with CAKUT and the only gene functioning in a signaling pathway that previously has been implicated in the pathogenesis of CAKUT.

SRGAP1 is a small GTPase-activating protein downstream of the extracellular ligand SLIT2 and the transmembrane receptor ROBO2 that was shown to limit the active state of the second messenger RAC1, which is important for cell migration (Li et al. 2006; Wong et al. 2001; Yamazaki et al. 2013). We and others recently reported on families with heterozygous mutations in ROBO2 as a rare monogenic cause of CAKUT (Bertoli-Avella et al. 2008; Dobson et al. 2013; Hwang et al. 2014; Jeanpierre et al. 2011; Lu et al. 2007). To obtain further evidence for heterozygous mutations in SLIT2–ROBO2 pathway genes on genetic ground, we performed high-throughput exon sequencing in SRGAP1 and SLIT2 in a cohort of 749 individuals with isolated CAKUT.

Hence, we chose to focus on investigating a potential causative role of the newly identified variants in SRGAP1 and to identify additional mutations in the ligand SLIT2 in other families with CAKUT.

Here, we describe and functionally characterize two novel heterozygous variants in SRGAP1 and three novel heterozygous variants in SLIT2. We demonstrate that Srgap1 is expressed in early mouse nephrogenic mesenchyme and that SRGAP1 and ROBO2 colocalize to the cap mesenchyme in developing rat kidney. Our functional studies further show that the newly identified SRGAP1 mutations cause augmented inhibition of RAC1, whereas the newly identified SLIT2 mutations diminish its inhibitory effect on neuronal cell migration. We thus present further evidence that heterozygous mutations in SLIT2, ROBO2, and SRGAP1 confer risk for developing CAKUT.

Materials and methods

Human subjects

Following informed consent, we obtained clinical data, blood samples, and pedigrees from individuals with CAKUT. The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the University of Michigan Medical School, Boston Children’s Hospital, and local IRBs according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients were included in the study if a diagnosis compatible with CAKUT was established by a pediatric nephrologist or (pediatric) urologist. The study comprised 749 individuals from 650 different families with CAKUT from 25 different pediatric nephrology units worldwide. Heterozygous exonic mutations in the following 23 genes that are known to cause isolated CAKUT in humans were excluded prior to this study: BMP4, BMP7, CDC5L, CHD1L, EYA1, GATA3, HNF1B, PAX2, RET, ROBO2, SALL1, SIX1, SIX2, SIX5, SOX17, UMOD, UPK3A, FRAS1, FREM2, FREM1, GRIP1, ITGA8, and GREM1. HNF1B deletions were excluded by quantitative PCR in individuals with the CAKUT phenotype of renal hypodysplasia.

Whole-exome sequencing

For a group of 26 CAKUT families, which remained genetically unsolved in two previous targeted sequencing studies, whole-exome sequencing (WES) and a variant burden analysis were performed as described previously (Boyden et al. 2012; Hwang et al. 2014; Kohl et al. 2014). Variants with minor allele frequencies <1 % in the Yale (1972 European subjects), NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (4300 European and 2202 African American subjects; last accessed November, 2012), dbSNP (version 135) or 1000 Genomes (1094 subjects of various ethnicities; May, 2011 data release) databases were selected and annotated for impact on the encoded protein and for conservation of the reference base and amino acid among orthologs across phylogeny.

For a variant burden analysis likely pathogenic variants detected in the present CAKUT cohort were compared to different, but also likely pathogenic variants of 2000 Swedish control exomes as previously described (Boyden et al. 2012). A Fisher exact test was used to determine significant enrichment of potentially pathogenic variants (p < 1.0E−5) in certain genes in the CAKUT cohort. Variants were considered “potentially pathogenic” if they were either missense variants affecting amino acid residues evolutionary conserved in vertebrates, splice-site or nonsense variants and absent from large variant databases (EVS, 1000 Genomes, Yale in-house variant database).

Candidate gene mutation analysis

All coding exons of SRGAP1 and SLIT2 were sequenced by microfluidic PCR (Fluidigm®) and next-generation sequencing (MiSeq®, Illumina) as described previously by our group (Halbritter et al. 2012, 2013). Exon-flanking oligonucleotide sequences for all coding exons of SRGAP1 and SLIT2 are available from the authors. Detected variants were filtered against public variant databases (1000 Genomes and NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project) and only novel variants were considered. Following evolutionary conservation analysis, identified mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing of genomic DNA.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence imaging (IF) was performed on rat kidney sections using a Leica SP5X system with an upright DM6000 compound microscope as previously described by the authors (Chaki et al. 2012). Images were processed with the Leica AF software suite. The following primary antibodies were used: SRGAP1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat# sc-81939), ROBO2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat# sc-31607), SIX2 (abcam, Cat# ab68908), and WT1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat# sc-192).

RAC1 and CDC42 activity assay

RAC1/CDC42 activity assays were performed according to Pellegrin and Mellor (2008). Briefly, the GST-PAK1 CRIB domain was purified from the BL21 (DE3) E. coli. HEK293T cells were transfected with wild-type or mutant SRGAP1 using FuGene HD transfection reagent (Promega). Cells were collected 48 h post-transfection, rinsed with PBS, lysed, and subjected to GST pulldown for 2 h at 4 °C. GST beads were washed 5 times followed by elution with sample buffer. GTP-bound CDC42 and RAC1 were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-CDC42 and anti-RAC1 antibodies (#610929 and #610651, BD Transduction Laboratories). Input controls were analyzed using anti-SRGAP1 (#H00057522-M07, Abnova) and anti-β-actin antibody (ab20272, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Anterior subventricular zone neuron migration assay

To make conditioned media of human SLIT2 and its mutants, 80 % confluent HEK293T cells were transiently transfected to express SLIT2 using calcium phosphate. 24 h after transfection, the cell media were replaced with fresh 10 % FCS DMEM and incubated in 5 % CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 3 days. SLIT2-conditioned medium was then collected from SLIT2 overexpressing HEK293T cells for functional anterior subventricular zone (SVZa) neuron migration assay. Migrating SVZa cells were dissected from the rostral migratory stream of postnatal rat brains at days 1–5 as described previously (Ward and Rao 2005). The SVZa cell explants were cultured in a 3:2:1 collagen:matrigel:DMEM mixed gel in the presence of wild-type human SLIT2 or mutant SLIT2-conditioned media for 24 h. SVZa cells were fixed in 4 % PFA and images were taken under a 10× DIC microscope. DIC images were converted in 8-bit gray-scale images and contrast was increased by 1 % (ImageJ software; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij). To identify and count migrated cells, matrigel shadows were electronically enlarged by 250 % leaving only migrated cells in the periphery visible (Supplementary Figure 6 online). In detail, matrigel shadows were selected using the “Fuzzy select” tool in GIMP2.8 image software (www.gimp.org) with a threshold of 15. The content of the selected area was deleted and filled with black using the “Bucket fill” tool. Subsequently, the black area was enlarged proportionally by increasing length and width by 250 % while keeping the center fixed. Following this masking procedure, remaining visible cells were counted using the “cell counter” plugin of ImageJ. Additionally, cell migration distances out of SVZa explants were measured in ImageJ. The length of two migration distances was measured per quadrant. Hence, 24 migration distances were obtained per triplicate. P values were calculated using the one-tailed Student’s t test.

Results

Exome sequencing and burden analysis in patients with CAKUT reveals likely pathogenic variants in SRGAP1

Since CAKUT are most frequently inherited in an autosomal dominant mode with incomplete penetrance, we hypothesized that different novel heterozygous mutations in the same gene in two or more unrelated individuals with CAKUT could represent monogenic causes for CAKUT. Hence, we performed whole-exome sequencing (WES) in 98 individuals from 26 unrelated families with isolated CAKUT. The 26 families included in the present WES study all had an affected child with a diagnosis of the CAKUT spectrum and they all remained genetically unsolved after 2 previous targeted sequencing studies comprising 23 known CAKUT genes (Hwang et al. 2014; Kohl et al. 2014). A burden analysis of novel potentially pathogenic variants in all 26 affected families revealed 29 genes as significantly enriched with novel potentially pathogenic variants as compared to 2000 Swedish control exomes. Since we only considered novel variants. we used a large control cohort regardless of their ethnical background as previously described by one of the co-authors (Boyden et al. 2012). We identified two affected individuals and one affected mother from two unrelated families harboring different heterozygous mutations in SRGAP1 (Table 1; Fig. 1). In family A4732 of European origin, the index patient A4732-21 and his mother were affected. A4732-21 was diagnosed prenatally with a right multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK). At 2.5 years of age there was no renal tissue detectable on renal ultrasound, indicating that the dysplastic kidney remnant had undergone complete involution (Fig. 1a). Ultrasound examination of the patient’s asymptomatic mother, A4732-12, demonstrated right non-obstructive duplex kidney (Fig. 1b). Both the index patient and his mother were heterozygous for the SRGAP1 mutation c.806G>A, leading to the amino acid substitution p.C269Y (Table 1; Fig. 1e–g). The missense mutation p.C269Y affects an amino acid residue conserved in vertebrates and is absent from public variant databases (>17,000 control chromosomes of the NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project and the 1000 Genomes Project) and from 1972 European subjects in the in-house Yale variant database. In the individual A1041-21 of Arabic/European descent with caudally fused kidneys (horseshoe kidney) including a multicystic dysplastic right upper pole, a hypodysplastic left upper pole and extra renal features, we detected the heterozygous SRGAP1 mutation c.1993C>A, causing an amino acid exchange in a conserved residue, p.P665T (Table 1; Fig. 1). The mutation was inherited from the father, who was clinically not affected. The father was not available for renal ultrasound examination. To identify additional families with SRGAP1 mutations, we screened for mutations in SRGAP1 in our previously described cohort of 845 affected individuals with CAKUT, which did not reveal additional affected families (Hwang et al. 2014; Sanchez et al. 1996). However, since potentially pathogenic variants in SRGAP1 were significantly enriched in our CAKUT cohort and since SRGAP1 is a molecular interactor of the ROBO2 receptor, a known CAKUT-causing gene, we chose to conduct further functional studies to investigate causality of the newly identified SRGAP1 mutations (Wong et al. 2001).

Ultrasonographic findings in two families with CAKUT and localization of newly identified mutations in SRGAP1 and SLIT2 cDNAs and proteins. a Renal ultrasonography of individual A4732-21 at age 6 months (SRGAP1 mutation) showing absence of renal tissue on the right side (black arrowhead) at the expected location adjacent to the liver (Li). The left kidney (K) shows compensatory hypertrophy. Prenatally, right multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK) was diagnosed (not shown). b Renal ultrasonography of the patient’s mother (SRGAP1 mutation) showing separation of the central echogenic complex in the right kidney (white arrowhead) indicating a non-obstructive duplex kidney. The left kidney is normal. c MCDK on the right side in individual A4736-21 (SLIT2 mutation) at age 3 months (white arrowheads denote two large cysts). d In the same individual, at age 2.5 years, no renal tissue was detectable on ultrasound on the right (black arrowhead), indicating complete involution of the MCDK. The left kidney (K) shows compensatory hypertrophy. e Exon structure of human SRGAP1 cDNA. The position of the start codon (ATG) and stop codon (TGA) are indicated. f Domain structure of the SRGAP1 protein. g Mutations detected in SRGAP1 in two families with CAKUT (family identifiers are underlined) are depicted as black arrows indicating their positions in relation to exons and protein domains (see also Table 1). h Exon structure of human SLIT2 cDNA. i Domain structure of SLIT2. j Mutations of SLIT2 detected in three unrelated individuals with CAKUT (see also Table 1). aa amino acids, bp base pairs, CT C-terminal cysteine knot domain, EGF epidermal growth factor-like domain, FCH Fes/CIP4 homology domain, IF-BAR inverse F-BAR domain, K kidney, LamG laminin G domain, L left, Li liver, LRR leucin-rich repeat domain, R right, RhoGAP GTPase-activator protein for Rho-like GTPases domain, SH3 Src homology 3 domain

SRGAP1 is expressed in early mouse nephrogenic mesenchyme and colocalizes with ROBO2 to the cap mesenchyme of developing rat kidneys

To examine the role of SRGAP1 during normal kidney development, we analyzed a Srgap1-lacZ reporter mouse line (Supplementary Figure 1 online). β-Galactosidase staining for cells from Srgap1 promoter-driven lacZ reporter expression at E11.5 detected Srgap1 in the developing nephrogenic mesenchyme, including the mesonephros and metanephros (Supplementary Figure 1 online). We confirmed expression of Srgap1 in metanephric mesenchyme at E13.5 and E14.5 by in situ hybridization (Supplementary Figure 2 online). Srgap1-expressing cells were absent from the E11.5 mouse nephric duct and the ureteric bud, which is consistent with what is described for Robo2 during early mouse kidney development (Grieshammer et al. 2004). This also is in line with microarray gene expression data in the Gudmap expression database (www.gudmap.org) (Supplementary Figure 3 online). To further relate SRGAP1 expression pattern to renal developmental phenotypes, we performed immunofluorescence staining of SRGAP1 in kidneys of embryonic and newborn rats (E16.5 and P0, respectively). We found Srgap1 to be expressed in rat kidney at E16.5 (Fig. 2a, b) and P0 (Fig. 2c, d), whereas we did not detect SRGAP1 in adult rat kidney (data not shown). During rat kidney development, we found SRGAP1 to be expressed in renal mesenchyme where it colocalizes with ROBO2 in SIX2-positive cap mesenchyme (Fig. 2a–d). We detected the strongest overlap of the SRGAP1 and ROBO2 signals at the ureteric bud-facing pole of the cap mesenchyme, strongly suggesting active SLIT2–ROBO2–SRGAP1 signaling at this site (Fig. 2b). These data are highly consistent with the CAKUT phenotype observed in individuals with heterozygous SRGAP1 mutations. Additionally, Srgap1 is expressed in developing podocytes, suggesting an additional function here, which is in line with previous work describing podocytes as Robo2-expressing cells (Fig. 2a, c, d; Supplementary Figure 4 online) (Fan et al. 2012; Lindenmeyer et al. 2010).

SRGAP1 is coexpressed with ROBO2 in cap mesenchyme in rat kidney at E16.5 and P0. Immunofluorescence microscopy of sections of rat kidneys at E16.5 (a, b) and at P0 (c, d). a, b ROBO2 (green) is expressed in SIX2-positive (blue-green) cap mesenchyme and developing glomeruli. SRGAP1 (red) colocalizes with ROBO2 in cap mesenchyme. b Enlargement from (a). Note that the overlap of ROBO2 and SRGAP1 (yellow) in cap mesenchyme is most prominent at the ureteric tip-facing pole of the cap mesenchyme (arrows) indicating active ROBO2–SRGAP1 signaling at this site. c, d ROBO2 is expressed in SIX2-positive cap mesenchyme (arrowheads) and in different stages of development of glomerular podocytes (C comma-shaped body, CL capillary loop stage glomerulus, G mature-appearing glomerulus). c Overview of renal cortex showing different stages of embryonic nephron development. The nephrogenic zone is marked by SIX2-positive cap mesenchyme directly underneath the renal capsule (arrowheads). Different stages of glomerular development on a gradient from early (C, CL) to late (G) express ROBO2 and SRGAP1. d SRGAP1 (red) is coexpressed with ROBO2 (green) in cap mesenchyme (arrowheads) and highly expressed in developing podocytes in capillary loop stages glomeruli (arrows). Scale bar 50 µm (color figure online)

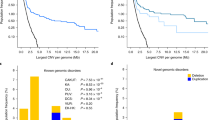

SRGAP1 mutations cause augmented inhibition of RAC1

SRGAP1 has been shown to act downstream of SLIT2–ROBO2 and to reduce the GTP-bound (active) state of RAC1, which is important for lamellipodial extension and retraction cycles in cell migration (Wong et al. 2001; Yamazaki et al. 2013). We hypothesized that the newly identified mutations in SRGAP1 in families with CAKUT may have an effect on RAC1 and CDC42 activity, which could alter cell migration of the cap mesenchyme during kidney development. Hence, we studied RAC1 and CDC42 activity using a PAK1 assay in human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293T) transiently overexpressing wild-type SRGAP1 versus mutant SRGAP1 proteins (Fig. 3). Interestingly, we found that the mutant SRGAP1 proteins p.C269Y and p.P665T shared an increased inhibition on RAC1 activity as compared to wild-type SRGAP1 indicating a gain-of-function effect of the mutations (Fig. 3). CDC42 activity was unchanged (Supplementary Figure 5 online).

RAC1 activity is reduced upon overexpression of SRGAP1 mutants in cultured HEK293T cells. a Active GTP-bound RAC1 precipitated by GST–PAK1 pulldown (PD) from HEK293T cells transfected with wild-type (WT) versus mutant SRGAP1 constructs. Note that HEK293T cells transfected with human SRGAP1 mutants C269Y and P665T exhibit an enhanced decrease in RAC1 activity compared to wild-type SRGAP1. The efficiency of SRGAP1 transfections and 5 % input control were confirmed by immunoblotting with anti-SRGAP1 and anti-actin antibodies, respectively. b Relative RAC1 activities (PAK1-bound RAC1/total RAC1) based on anti-RAC1 immunoblot signal intensities in a. Ratios are normalized to mock transfection. a and b represent 5 experiments each. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test); Error bars indicate one standard deviation (n = 3)

Novel pathogenic variants in SLIT2 cause CAKUT in humans

Next, we aimed to identify additional CAKUT-causing genes that are a component in the SLIT2–ROBO2–SRGAP1 signaling pathway. We and others have recently published that heterozygous ROBO2 mutations cause CAKUT in humans and mice (Hwang et al. 2014; Lu et al. 2007). Intriguingly, mutated SLIT2 has been reported to cause a CAKUT phenotype in a knockout mouse model making it a promising candidate gene for human CAKUT (Grieshammer et al. 2004). To identify SLIT2 mutations in patients with CAKUT we utilized high-throughput exon sequencing to screen for mutations in SLIT2 in 749 affected individuals with CAKUT (Hwang et al. 2014; Sanchez et al. 1996). We identified three unrelated individuals with three different heterozygous SLIT2 missense mutations affecting conserved amino acid residues which were absent from public variant databases (Table 1; Fig. 1h–j). Individual A3748-21 with multiple subcortical cysts in both kidneys had the mutation SLIT2 c.292G>A, p.A98T (Table 1; Fig. 1h–j). Individual A4736-21 with right MCDK was found to have SLIT2 c.1697G>A, p.S566N (Table 1; Fig. 1h–j). Interestingly, as described in individual A4732-21 with an SRGAP1 mutation, this individual also showed MCDK and complete involution (Fig. 1c–d). The third individual, A3468-21, who was diagnosed with right renal agenesis at 14 years of age, had the mutation SLIT2 c.2712A>T, p.K904N (Table 1; Fig. 1h–j).

SLIT2 mutations cause reduced inhibition of cell migration

Knockout mice lacking Slit2 develop supernumerary ureteric buds that remain inappropriately connected to the nephric duct, resulting in CAKUT in the form of multiple ureters and fused dysplastic kidneys (Grieshammer et al. 2004). The SLIT2 protein has a well-studied function as a chemorepellent in neuronal cell migration (Brose et al. 1999; Nguyen Ba-Charvet et al. 1999). Given the CAKUT phenotype of the Slit2 knockout mouse model, we hypothesized that the newly identified mutations in SLIT2 would alter its chemorepulsive activity. To test this hypothesis, we studied the function of SLIT2 mutants on anterior subventricular zone (SVZa) cell migration (Ward and Rao 2005). Neuron precursor cells from the rat olfactory bulb express ROBO2 receptors and are repelled by wild-type SLIT2 (Nguyen-Ba-Charvet et al. 2004). In this model, we overexpressed wild-type SLIT2 and mutants in HEK293T cells and harvested SLIT2-conditioned media 72 h after transfection. SVZa cell migration in the presence of wild-type SLIT2 or mutant-conditioned media was analyzed after 24 h by counting migrated cells (Fig. 4; Supplementary Figures 6 and 7 online). We observed the expected radial migration of cells in the conditioned media from mock-transfected HEK293T cells. SLIT2 wild-type conditioned media strongly inhibited cell migration (Fig. 4; Supplementary Figures 6 and 7 online). However, the SLIT2 mutations p.A98T, p.S566N, and p.K904N compromised the inhibition of SVZa cell migration, suggesting a loss-of-function effect (Fig. 4; Supplementary Figures 6 and 7 online).

SLIT2 mutations identified in CAKUT patients compromise its inhibition of SVZa neuronal migration. a Representative DIC images show SVZa neuronal migration after 24 h in the presence of SLIT2 wild-type (WT) or SLIT2 mutants (A98T, S566N, K904N) conditioned media. Media from mock-transfected HEK293T cells were used as a negative control. Note that wild-type SLIT2 inhibits neuronal migration whereas the SLIT2 mutants show a diminished inhibition. Dot circles in processed image column represent the areas where the number of migrated cells out of SVZa explants and migration distance were quantified (see also Supplementary Figure 6 online). b Quantification of migrated SVZa cell counts in a. Note wild-type SLIT2 has less migrated cells out of SVZa explants. SLIT2 mutants A98T, S566N, and K904N show a diminished inhibitory effect on migrated cell counts. c Quantification of average SVZa cell migration distances in a. Note wild-type SLIT2 inhibits migration of SVZa cells. SLIT2 mutants A98T, S566N, and K904N show a reduced inhibitory effect on migration indicating partial loss-of-function. Scale bar 100 µm. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test); Error bars indicate one standard deviation (n = 3)

Discussion

In the present study, we identified two different heterozygous mutations in SRGAP1 and three different heterozygous mutations in SLIT2 in families with isolated CAKUT. We showed that Srgap1 is specifically expressed in the early nephrogenic mesenchyme in mice and the metanephric mesenchyme in rats where it colocalizes with the transmembrane receptor ROBO2 during metanephric kidney development. We demonstrated that the newly discovered SRGAP1 mutations have a gain-of-function effect in a RAC1 activity assay and that the mutated SLIT2 proteins exhibit a loss-of-function effect in repelling migrating SLIT2-sensitive cells in a SVZa assay. Although we have not studied the effect of the newly identified mutations in knock-in murine transgenic models to generate direct evidence for a causative role of the newly described mutations, causality is strongly supported by the aforementioned assays and by genetic evidence on a gene and variant level according to recent guidelines (MacArthur et al. 2014). Hence, we presented evidence that heterozygous mutations in the SLIT2–ROBO2–SRGAP1 signaling pathway may confer risk for developing CAKUT in humans.

Our current model of pathogenesis in humans with CAKUT and SLIT2–ROBO2–SRGAP1 mutations is based on accumulating evidence that imbalances of a tightly balanced small GTPase network interferes with migrating cells of the ureteric bud and the metanephric mesenchyme during kidney development. The ligand SLIT2 is expressed in the nephric duct, ureteric bud, and ureteric tips (Supplementary Figure 3 online), whereas its receptor ROBO2 is expressed in the adjacent metanephric mesenchyme. The present work adds SRGAP1 as a downstream effector to the established SLIT2–ROBO2 signaling pathway during kidney development. The newly identified deactivating SLIT2 mutations and activating SRGAP1 mutations do not allow a harmonic conclusion that either up- or down-regulation of SLIT2/ROBO2/SRGAP1 signaling causes CAKUT, because our study showed that gain-of-function mutations in SRGAP1, as well as loss-of-function mutations in SLIT2 may be pathogenic. Instead, we conclude that both up- or down-regulation of a tightly balanced small GTPase network can lead to disease. Following our in vitro functional studies, it will be necessary to directly observe the behavior of the mutated proteins during metanephric kidney development, preferably in transgenic knock-in animal models.

The predominant phenotypes in individuals with heterozygous mutations in either SLIT2 or SRGAP1 were multicystic dysplastic kidneys that undergo complete involution during childhood. This fact is suggestive for a pathway-phenotype correlation, although more cases and larger pedigrees are needed before we can draw this conclusion and attribute monogenic causality. The presence of unilateral MCDK as a genetic disease seems counterintuitive. However, this is a very common presentation of monogenic CAKUT cases and does not argue against a genetic etiology (Hwang et al. 2014). In family A1041, the affected child inherited the SRGAP1 mutation from a healthy father with a normal renal ultrasound. This family may represent a case of incomplete penetrance, which is a common finding in CAKUT, and thus does not exclude causality. In this case, the treating physician had lost contact with the family and we were not able to obtain renal ultrasounds in other family members.

In summary, by discovery of mutations in SLIT2 and SRGAP1, we implicated multiple components of a coherent signaling pathway in the pathogenesis of human CAKUT.

Web resources

1000 Genomes Browser, http://browser.1000genomes.org.

Ensembl Genome Browser, http://www.ensembl.org.

Exome Variant Server, http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS.

Gudmap (GenitoUrinary Molecular Anatomy Project), http://www.gudmap.org.

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.omim.org.

Polyphen2, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2.

SeattleSeq Annotation 138, http://snp.gs.washington.edu/SeattleSeqAnnotation138/.

Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant (SIFT), http://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg.

UCSC Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway.

References

Bertoli-Avella AM, Conte ML, Punzo F, de Graaf BM, Lama G, La Manna A, Polito C, Grassia C, Nobili B, Rambaldi PF, Oostra BA, Perrotta S (2008) ROBO2 gene variants are associated with familial vesicoureteral reflux. J Am Soc Nephrol 19:825–831. doi:10.1681/ASN.2007060692

Boyden LM, Choi M, Choate KA, Nelson-Williams CJ, Farhi A, Toka HR, Tikhonova IR, Bjornson R, Mane SM, Colussi G, Lebel M, Gordon RD, Semmekrot BA, Poujol A, Valimaki MJ, De Ferrari ME, Sanjad SA, Gutkin M, Karet FE, Tucci JR, Stockigt JR, Keppler-Noreuil KM, Porter CC, Anand SK, Whiteford ML, Davis ID, Dewar SB, Bettinelli A, Fadrowski JJ, Belsha CW, Hunley TE, Nelson RD, Trachtman H, Cole TR, Pinsk M, Bockenhauer D, Shenoy M, Vaidyanathan P, Foreman JW, Rasoulpour M, Thameem F, Al-Shahrouri HZ, Radhakrishnan J, Gharavi AG, Goilav B, Lifton RP (2012) Mutations in kelch-like 3 and cullin 3 cause hypertension and electrolyte abnormalities. Nature 482:98–102. doi:10.1038/nature10814

Brakeman P (2008) Vesicoureteral reflux, reflux nephropathy, and end-stage renal disease. Adv Urol. doi:10.1155/2008/508949

Brose K, Bland KS, Wang KH, Arnott D, Henzel W, Goodman CS, Tessier-Lavigne M, Kidd T (1999) Slit proteins bind Robo receptors and have an evolutionarily conserved role in repulsive axon guidance. Cell 96:795–806

Chaki M, Airik R, Ghosh AK, Giles RH, Chen R, Slaats GG, Wang H, Hurd TW, Zhou W, Cluckey A, Gee HY, Ramaswami G, Hong CJ, Hamilton BA, Cervenka I, Ganji RS, Bryja V, Arts HH, van Reeuwijk J, Oud MM, Letteboer SJ, Roepman R, Husson H, Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O, Yasunaga T, Walz G, Eley L, Sayer JA, Schermer B, Liebau MC, Benzing T, Le Corre S, Drummond I, Janssen S, Allen SJ, Natarajan S, O’Toole JF, Attanasio M, Saunier S, Antignac C, Koenekoop RK, Ren H, Lopez I, Nayir A, Stoetzel C, Dollfus H, Massoudi R, Gleeson JG, Andreoli SP, Doherty DG, Lindstrad A, Golzio C, Katsanis N, Pape L, Abboud EB, Al-Rajhi AA, Lewis RA, Omran H, Lee EY, Wang S, Sekiguchi JM, Saunders R, Johnson CA, Garner E, Vanselow K, Andersen JS, Shlomai J, Nurnberg G, Nurnberg P, Levy S, Smogorzewska A, Otto EA, Hildebrandt F (2012) Exome capture reveals ZNF423 and CEP164 mutations, linking renal ciliopathies to DNA damage response signaling. Cell 150:533–548. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.028

Costantini F, Shakya R (2006) GDNF/Ret signaling and the development of the kidney. BioEssays 28:117–127. doi:10.1002/bies.20357

Dobson MG, Darlow JM, Hunziker M, Green AJ, Barton DE, Puri P (2013) Heterozygous non-synonymous ROBO2 variants are unlikely to be sufficient to cause familial vesicoureteric reflux. Kidney Int 84:327–337. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.100

Durbec P, Marcos-Gutierrez CV, Kilkenny C, Grigoriou M, Wartiowaara K, Suvanto P, Smith D, Ponder B, Costantini F, Saarma M et al (1996) GDNF signalling through the Ret receptor tyrosine kinase. Nature 381:789–793. doi:10.1038/381789a0

Fan X, Li Q, Pisarek-Horowitz A, Rasouly HM, Wang X, Bonegio RG, Wang H, McLaughlin M, Mangos S, Kalluri R, Holzman LB, Drummond IA, Brown D, Salant DJ, Lu W (2012) Inhibitory effects of Robo2 on nephrin: a crosstalk between positive and negative signals regulating podocyte structure. Cell Rep 2:52–61. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2012.06.002

Gbadegesin RA, Brophy PD, Adeyemo A, Hall G, Gupta IR, Hains D, Bartkowiak B, Rabinovich CE, Chandrasekharappa S, Homstad A, Westreich K, Wu G, Liu Y, Holanda D, Clarke J, Lavin P, Selim A, Miller S, Wiener JS, Ross SS, Foreman J, Rotimi C, Winn MP (2013) TNXB mutations can cause vesicoureteral reflux. J Am Soc Nephrol 24:1313–1322. doi:10.1681/ASN.2012121148

Grieshammer U, Le M, Plump AS, Wang F, Tessier-Lavigne M, Martin GR (2004) SLIT2-mediated ROBO2 signaling restricts kidney induction to a single site. Dev Cell 6:709–717 (pii: S153458070400108X)

Halbritter J, Diaz K, Chaki M, Porath JD, Tarrier B, Fu C, Innis JL, Allen SJ, Lyons RH, Stefanidis CJ, Omran H, Soliman NA, Otto EA (2012) High-throughput mutation analysis in patients with a nephronophthisis-associated ciliopathy applying multiplexed barcoded array-based PCR amplification and next-generation sequencing. J Med Genet 49:756–767. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100973

Halbritter J, Porath JD, Diaz KA, Braun DA, Kohl S, Chaki M, Allen SJ, Soliman NA, Hildebrandt F, Otto EA (2013) Identification of 99 novel mutations in a worldwide cohort of 1,056 patients with a nephronophthisis-related ciliopathy. Hum Genet 132:865–884. doi:10.1007/s00439-013-1297-0

Humbert C, Silbermann F, Morar B, Parisot M, Zarhrate M, Masson C, Tores F, Blanchet P, Perez MJ, Petrov Y, Khau Van Kien P, Roume J, Leroy B, Gribouval O, Kalaydjieva L, Heidet L, Salomon R, Antignac C, Benmerah A, Saunier S, Jeanpierre C (2014) Integrin alpha 8 recessive mutations are responsible for bilateral renal agenesis in humans. Am J Hum Genet 94:288–294. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.12.017

Hwang DY, Dworschak GC, Kohl S, Saisawat P, Vivante A, Hilger AC, Reutter HM, Soliman NA, Bogdanovic R, Kehinde EO, Tasic V, Hildebrandt F (2014) Mutations in 12 known dominant disease-causing genes clarify many congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Kidney Int 85:1429–1433. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.508

Ichikawa I, Kuwayama F, Pope JC, Stephens FD, Miyazaki Y (2002) Paradigm shift from classic anatomic theories to contemporary cell biological views of CAKUT. Kidney Int 61:889–898. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00188.x

Jeanpierre C, Mace G, Parisot M, Moriniere V, Pawtowsky A, Benabou M, Martinovic J, Amiel J, Attie-Bitach T, Delezoide AL, Loget P, Blanchet P, Gaillard D, Gonzales M, Carpentier W, Nitschke P, Tores F, Heidet L, Antignac C, Salomon R (2011) RET and GDNF mutations are rare in fetuses with renal agenesis or other severe kidney development defects. J Med Genet 48:497–504. doi:10.1136/jmg.2010.088526

Kohl S, Hwang DY, Dworschak GC, Hilger AC, Saisawat P, Vivante A, Stajic N, Bogdanovic R, Reutter HM, Kehinde EO, Tasic V, Hildebrandt F (2014) Mild recessive mutations in six fraser syndrome-related genes cause isolated congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. J Am Soc Nephrol. doi:10.1681/ASN.2013101103

Li X, Chen Y, Liu Y, Gao J, Gao F, Bartlam M, Wu JY, Rao Z (2006) Structural basis of Robo proline-rich motif recognition by the srGAP1 Src homology 3 domain in the Slit-Robo signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 281:28430–28437. doi:10.1074/jbc.M604135200

Lindenmeyer MT, Eichinger F, Sen K, Anders HJ, Edenhofer I, Mattinzoli D, Kretzler M, Rastaldi MP, Cohen CD (2010) Systematic analysis of a novel human renal glomerulus-enriched gene expression dataset. PLoS One 5:e11545. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011545

Lu W, van Eerde AM, Fan X, Quintero-Rivera F, Kulkarni S, Ferguson H, Kim HG, Fan Y, Xi Q, Li QG, Sanlaville D, Andrews W, Sundaresan V, Bi W, Yan J, Giltay JC, Wijmenga C, de Jong TP, Feather SA, Woolf AS, Rao Y, Lupski JR, Eccles MR, Quade BJ, Gusella JF, Morton CC, Maas RL (2007) Disruption of ROBO2 is associated with urinary tract anomalies and confers risk of vesicoureteral reflux. Am J Hum Genet 80:616–632. doi:10.1086/512735

MacArthur DG, Manolio TA, Dimmock DP, Rehm HL, Shendure J, Abecasis GR, Adams DR, Altman RB, Antonarakis SE, Ashley EA, Barrett JC, Biesecker LG, Conrad DF, Cooper GM, Cox NJ, Daly MJ, Gerstein MB, Goldstein DB, Hirschhorn JN, Leal SM, Pennacchio LA, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Sunyaev SR, Valle D, Voight BF, Winckler W, Gunter C (2014) Guidelines for investigating causality of sequence variants in human disease. Nature 508:469–476. doi:10.1038/nature13127

McPherson E, Carey J, Kramer A, Hall JG, Pauli RM, Schimke RN, Tasin MH (1987) Dominantly inherited renal adysplasia. Am J Med Genet 26:863–872. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320260413

Nguyen Ba-Charvet KT, Brose K, Marillat V, Kidd T, Goodman CS, Tessier-Lavigne M, Sotelo C, Chedotal A (1999) Slit2-Mediated chemorepulsion and collapse of developing forebrain axons. Neuron 22:463–473

Nguyen-Ba-Charvet KT, Picard-Riera N, Tessier-Lavigne M, Baron-Van Evercooren A, Sotelo C, Chedotal A (2004) Multiple roles for slits in the control of cell migration in the rostral migratory stream. J Neurosci 24:1497–1506. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4729-03.2004

Pellegrin S, Mellor H (2008) Rho GTPase activation assays. Curr Protoc Cell Biol 38:14.8.1–14.8.19. doi:10.1002/0471143030.cb1408s38

Pepicelli CV, Kispert A, Rowitch DH, McMahon AP (1997) GDNF induces branching and increased cell proliferation in the ureter of the mouse. Dev Biol 192:193–198. doi:10.1006/dbio.1997.8745

Piper M, Georgas K, Yamada T, Little M (2000) Expression of the vertebrate Slit gene family and their putative receptors, the Robo genes, in the developing murine kidney. Mech Dev 94:213–217

Rasouly HM, Lu W (2013) Lower urinary tract development and disease. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med 5:307–342. doi:10.1002/wsbm.1212

Saisawat P, Kohl S, Hilger AC, Hwang DY, Yung Gee H, Dworschak GC, Tasic V, Pennimpede T, Natarajan S, Sperry E, Matassa DS, Stajic N, Bogdanovic R, de Blaauw I, Marcelis CL, Wijers CH, Bartels E, Schmiedeke E, Schmidt D, Marzheuser S, Grasshoff-Derr S, Holland-Cunz S, Ludwig M, Nothen MM, Draaken M, Brosens E, Heij H, Tibboel D, Herrmann BG, Solomon BD, de Klein A, van Rooij IA, Esposito F, Reutter HM, Hildebrandt F (2014) Whole-exome resequencing reveals recessive mutations in TRAP1 in individuals with CAKUT and VACTERL association. Kidney Int 85:1310–1317. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.417

Sanchez MP, Silos-Santiago I, Frisen J, He B, Lira SA, Barbacid M (1996) Renal agenesis and the absence of enteric neurons in mice lacking GDNF. Nature 382:70–73. doi:10.1038/382070a0

Sanna-Cherchi S, Sampogna RV, Papeta N, Burgess KE, Nees SN, Perry BJ, Choi M, Bodria M, Liu Y, Weng PL, Lozanovski VJ, Verbitsky M, Lugani F, Sterken R, Paragas N, Caridi G, Carrea A, Dagnino M, Materna-Kiryluk A, Santamaria G, Murtas C, Ristoska-Bojkovska N, Izzi C, Kacak N, Bianco B, Giberti S, Gigante M, Piaggio G, Gesualdo L, Kosuljandic Vukic D, Vukojevic K, Saraga-Babic M, Saraga M, Gucev Z, Allegri L, Latos-Bielenska A, Casu D, State M, Scolari F, Ravazzolo R, Kiryluk K, Al-Awqati Q, D’Agati VD, Drummond IA, Tasic V, Lifton RP, Ghiggeri GM, Gharavi AG (2013) Mutations in DSTYK and dominant urinary tract malformations. N Engl J Med 369:621–629. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1214479

Smith JM, Stablein DM, Munoz R, Hebert D, McDonald RA (2007) Contributions of the Transplant Registry: the 2006 Annual Report of the North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies (NAPRTCS). Pediatr Transplant 11:366–373. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3046.2007.00704.x

Tang MJ, Worley D, Sanicola M, Dressler GR (1998) The RET-glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) pathway stimulates migration and chemoattraction of epithelial cells. J Cell Biol 142:1337–1345

Vega QC, Worby CA, Lechner MS, Dixon JE, Dressler GR (1996) Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor activates the receptor tyrosine kinase RET and promotes kidney morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 93:10657–10661

Vivante A, Kohl S, Hwang DY, Dworschak GC, Hildebrandt F (2014) Single-gene causes of congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) in humans. Pediatr Nephrol 29:695–704. doi:10.1007/s00467-013-2684-4

Ward ME, Rao Y (2005) Investigations of neuronal migration in the central nervous system. Methods Mol Biol 294:137–156

Wong K, Ren XR, Huang YZ, Xie Y, Liu G, Saito H, Tang H, Wen L, Brady-Kalnay SM, Mei L, Wu JY, Xiong WC, Rao Y (2001) Signal transduction in neuronal migration: roles of GTPase activating proteins and the small GTPase Cdc42 in the Slit-Robo pathway. Cell 107:209–221

Yamazaki D, Itoh T, Miki H, Takenawa T (2013) srGAP1 regulates lamellipodial dynamics and cell migratory behavior by modulating Rac1 activity. Mol Biol Cell 24:3393–3405. doi:10.1091/mbc.E13-04-0178

Acknowledgments

We thank the physicians and the participating families, Anna Pisarek-Horowitz for assistance with early mouse embryonic kidney dissection, and Nine V. A. M. Knoers for mutation analysis of SRGAP1 in additional affected individuals. F.H. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the Warren E. Grupe Professor of Pediatrics. This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01DK088767 to FH; R01DK078226 to WL), by the March of Dimes Foundation (6-FY11-241 to FH; 1-FY12-426 to WL), by the Excellence Initiative of the German Federal and State Governments (EXC 294 to TBH), by the Excellence Initiative of the German Research Foundation (GSC-4, Spemann Graduate School to CS), by grants from the Dutch Kidney Foundation (KSTP12_010 to AMvE; CP11.18 to KYR), by Fonds NutsOhra (1303-070 to AMvE), and by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program FP7/2009 (305608, EURenOmics to GvdH and KYR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

D.-Y. Hwang, S. Kohl and X. Fan contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

439_2015_1570_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Supplementary material 1 (PDF 4287 kb) Supplementary Figure 1. Srgap1 is expressed in early mouse developing kidney. Supplementary Figure 2. Srgap1 is expressed in mouse metanephric mesenchyme and developing glomeruli at E13.5 and E14.5. Supplementary Figure 3. Srgap1 and Robo2 are coexpressed in metanephric mesenchyme, cap mesenchyme, and renal corpuscles in mice at E.11.5 and E15.5. Slit2 is expressed in ureteric bud and ureteric tip at E11.5 and E15.5. Supplementary Figure 4. SRGAP1 partially colocalizes with ROBO2 in developing podocytes. Supplementary Figure 5. Overexpression of mutant SRGAP1 does not alter CDC42 activity in cultured HEK293T cells. Supplementary Figure 6. Mutations in SLIT2 detected in individuals with CAKUT reduce the chemorepulsive effect of SLIT2

439_2015_1570_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Supplementary material 2 (PDF 26 kb) Supplementary Figure 7. Similar amounts of SLIT2 proteins present in the conditioned media used for the SVZa assay (Figure 4)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hwang, DY., Kohl, S., Fan, X. et al. Mutations of the SLIT2–ROBO2 pathway genes SLIT2 and SRGAP1 confer risk for congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Hum Genet 134, 905–916 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-015-1570-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-015-1570-5