Abstract

On the basis of the converging evidence showing regulation of drinking behavior by 5-HT3AB receptors and the serotonin transporter, we hypothesized that the interactive effects of genetic variations in the genes HTR3A, HTR3B, and SLC6A4 confer greater susceptibility to alcohol dependence (AD) than do their effects individually. We examined the associations of AD with 22 SNPs across HTR3A, HTR3B, and two functional variants in SLC6A4 in 500 AD and 280 healthy control individuals of European descent. We found that the alleles of the low-frequency SNPs rs33940208:T in HTR3A and rs2276305:A in HTR3B were inversely and nominally significantly associated with AD with odds ratio (OR) and 95 % confidence interval of 0.212 and 0.073, 0.616 (P = 0.004) and 0.261 and 0.088, 0.777 (P = 0.016), respectively. Further, our gene-by-gene interaction analysis revealed that two four-variant models that differed by only one SNP carried a risk for AD (empirical P < 1 × 10−6 for prediction accuracy of the two models based on 106 permutations). Subsequent analysis of these two interaction models revealed an OR of 2.71 and 2.80, respectively, for AD (P < 0.001) in carriers of genotype combinations 5′-HTTLPR:LL/LS(SLC6A4)–rs1042173:TT/TG(SLC6A4)–rs1176744:AC(HTR3B)–rs3782025:AG(HTR3B) and 5′-HTTLPR:LL/LS(SLC6A4)–rs10160548:GT/TT(HTR3A)–rs1176744:AC(HTR3B)–rs3782025:AG(HTR3B). Combining all five genotypes resulted in an OR of 3.095 (P = 2.0 × 10−4) for AD. Inspired by these findings, we conducted the analysis in an independent sample, OZ-ALC-GWAS (N = 6699), obtained from the NIH dbGAP database, which confirmed the findings, not only for all three risk genotype combinations (Z = 4.384, P = 1.0 × 10−5; Z = 3.155, P = 1.6 × 10−3; and Z = 3.389, P = 7.0 × 10−4, respectively), but also protective effects for rs33940208:T (χ 2 = 3.316, P = 0.0686) and rs2276305:A (χ 2 = 7.224, P = 0.007). These findings reveal significant interactive effects among variants in SLC6A4–HTR3A–HTR3B affecting AD. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings and characterize the molecular mechanisms underlying these effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Candidate gene-based association studies performed over many years have focused on various genes within the serotonergic system to identify susceptibility variants for alcohol dependence (AD). Serotonin mediates the reward effects of alcohol along with a network of other neurotransmitters. Previous serotonergic gene-based association studies in AD have been analyzed mostly for single-gene effects, especially in the serotonin transporter (5-HTT) gene (SLC6A4), that yielded modest effect sizes. Yet the serotonergic system is complex, consisting of numerous pre- and post-synaptic receptor subtypes in addition to the transporter system that regulates synaptic amounts of serotonin (Hayes and Greenshaw 2011). Among the serotonergic receptor subtypes in the human nervous system, 5-HT3 receptors are the only known ion-channel receptors evoking fast excitation of serotonergic neurons (Sugita et al. 1992). Acute exposure to alcohol potentiates 5-HT3 receptors at concentrations that produce intoxication (Narahashi et al. 2001; Sung et al. 2000), possibly through altered receptor affinity for serotonin (Narahashi et al. 2001), stabilization of open-channel state (Zhou et al. 1998), or increased release of serotonin (Lovinger 1997). Chronic heavy drinking depletes pre-synaptic serotonin reserves, causing a hypo-serotonergic state that may up-regulate post-synaptic 5-HT3 receptors (Johnson 2000).

The 5-HT3 receptors are assembled in homo- or hetero-pentamers formed by 5-HT3A and 5-HT3B subunits. The 5-HT3A subunit harbors the serotonin binding site (Hodge et al. 2004), and the 5-HT3B subunit is important for trafficking and stabilizing of the 5-HT3AB receptor complex at the cell membrane (Massoura et al. 2011). Two lines of evidence suggest a concerted effect of both subunits on serotonergic dysfunction underlying AD. The first is based on the location of the subunits within the human brain. Whilst the 5-HT3A homomers are uniformly located in various parts of the central and peripheral nervous systems, the 5-HT3AB heteromers are located predominantly in mesocorticolimbic structures implicated in alcohol and other drug addictions. The second is evidence from biochemical studies of greater conductivity with 5-HT3AB hetero-pentamers compared with 5-HT3A homo-pentamers (Lochner and Lummis 2010), whereas 5-HT3B by itself appears to be non-functional (Davies et al. 1999).

The genes encoding 5-HT3AB, namely, HTR3A and HTR3B (Davies et al. 1999), are located next to each other on chromosome 11q23.1 spanning a 90-kbp region (Miyake et al. 1995). So far, only two studies have examined the associations of HTR3A and HTR3B with AD (Ducci et al. 2009; Enoch et al. 2011). In a population of Finnish alcoholics who also had antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), Ducci et al. (2009) showed that the A allele of intronic HTR3B SNP rs3782025 was associated with a higher risk of AD + ASPD. A more recent study conducted in African-American AD men reported an association of the C allele of non-synonymous exonic HTR3B SNP rs1176744 with a higher risk for AD with a relatively large effect size for a complex trait (OR = 1.6; 95 % CI 2.1, 16.6) (Enoch et al. 2011). Additionally, in a pharmacogenetic trial based on an a priori hypothesis, Johnson et al. (2011) demonstrated the influence of functional variants of the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) on conductivity via post-synaptic 5-HT3AB receptors. In that study, drinking severity was improved more by the 5-HT3 antagonist ondansetron in Caucasian alcoholics carrying two genotypes (5′-HTTLPR:LL and rs1042173:TT) in SLC6A4 that previously were characterized as associated with lower expression in alcoholics (Johnson et al. 2008; Seneviratne et al. 2009b).

In view of these molecular and genetic findings, we hypothesized that, in alcoholics, the combined effects of genetic variations regulating synaptic serotonin levels, coupled with greater expression and function of 5-HT3AB, may confer greater susceptibility to AD than they do individually. To test this hypothesis, in a population of AD and healthy individuals of European descent, we evaluated associations of HTR3A and HTR3B SNPs evenly covering the two genes and their interactions with the SLC6A4 5′-HTTLPR:LL and rs1042173:TT genotypes. Subsequently, we assessed the reproducibility of our findings in a much larger dataset from a genome-wide association study called OZ-ALC-GWAS.

Materials and methods

Primary analysis

Samples

The DNA samples used in the primary analysis were initially from 822 unrelated self-identified Caucasian subjects aged 18–65 years, which included 519 AD subjects and 303 controls. Three hundred and twenty-three of the AD individuals were enrolled at The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and the remainder at the University of Virginia. All AD individuals were currently drinking with no other DSM-IV axis I diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association 1994) other than nicotine dependence scored >8 on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Bohn et al. 1995), and were part of two out-patient clinical trials that tested medications for alcoholism. The ethnicity- and age-matched control individuals were selected from a large genetic study on nicotine addiction and were recruited primarily from the Mid-South States in the US (Texas, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Arkansas) during 1999–2005 (Li et al. 2005; Seneviratne et al. 2009a; Sun et al. 2008). The control individuals had no history of substance abuse or other DSM-IV axis I diagnoses. At all sites that recruited case or control subjects, DSM-IV axis I disorders were diagnosed using the Structured Clinical Interview (First et al. 1994) for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (American Psychiatric Association 1994) Axis I Disorders.

Percentage of females in the AD population was 30.4 and 64.0 % in the control population. The mean age (years ± SD) at study entry for males and females in the AD group was 43.87 ± 10.83 and 43.79 ± 12.81 in the control group. All participants provided written informed consent according to a protocol approved by all involved Institutional Review Boards.

Genotyping

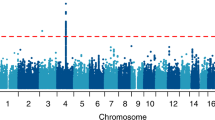

Detailed information on all SNP locations, chromosomal positions, allelic variants, minor allele frequency, and primer/probe sequences is summarized in Supplementary Table 1. All SNPs were selected from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) dbSNP database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/) on the basis of their location within the gene, high heterozygosity (minor allele frequency ≥0.05) for common variants, and biological significance for uniform coverage of the gene (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). The three low-frequency variants (i.e., rs33940208 in HTR3A and rs2276305 and rs17116138 in HTR3B) were examined, as they were located close to known common functional variants or in exonic regions.

The DNA extractions and genotyping of all SNPs and the long (L) and short (S) alleles of 5′-HTTLPR were carried out as described in our previous publication (Seneviratne et al. 2009b). Briefly, SNP genotyping was performed with 50 ng of DNA amplified in a total volume of 10 μl containing 0.25 μl of MGB probe and TaqMan universal PCR master mix. Allelic discrimination analyses were performed on the ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system. To ensure the quality of genotyping, four no-template negative controls and four positive controls were added to each 384-well plate. The 5-HTTLPR L and S alleles were also genotyped with 50 ng of genomic DNA PCR amplified with the primers listed in Supplementary Table 1 and the PCR conditions as described in our earlier publication (Seneviratne et al. 2009b). The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 3.5 % agarose gel, and the amplicons were identified using ethidium bromide staining. About 5 % of the sample was genotyped in duplicate for additional quality control.

Assessment of sample admixture using ancestry-informative markers

The DNA samples from all 822 subjects were genotyped with 24 ancestry-informative markers (AIMs) to test for potential population stratification. These markers have high-frequency differences for South American/European ancestry and European/West African ancestry (Mao et al. 2007). For detailed information, please see our previous publications (Johnson et al. 2011; Seneviratne et al. 2009a). The program Structure (http://pritch.bsd.uchicago.edu/software/structure2_2.html) was run using the 24 AIM datasets to assess population substructure and to estimate genetic ancestry proportion scores for each participant. We analyzed the data set with K = 2 through K = 10, and the simulation parameters were set to 10,000 burn-ins and 10,000 Markov chain Monte Carlo iterations. The K value with the highest probability of capturing stratification was 3; hence, we obtained the ancestry proportion estimates by analyzing the dataset assuming three parental populations (K = 3) and the presence of population admixture. The average rate of missing genotype information for the 24 AIMs was less than 5 % for the entire dataset of 822 subjects. A small group of 42 individuals was identified with 0 % probability to belong to the main population cluster, and thus was excluded from all statistical association analyses described below. A summary of clustering results for the 780 subjects is given in Supplementary Figure 1. Individual genetic ancestry proportion scores for each participant were used as covariates in all association analysis models.

Statistical analysis

All variants except for rs1176746 within HTR3B conformed to the Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE). Hence, rs1176746 was excluded from association analyses, and the remaining variants (10 HTR3A SNPs, 11 HTR3B SNPs, and 2 SLC6A4 variants) were tested for single- and multiple-locus associations with AD.

Single-locus association analysis with AD

Logistic regression and Chi-square tests were performed in SAS (v. 9.1) to analyze genotype and allelic associations of all 23 individual SNPs in HTR3A, HTR3B, and SLC6A4 with AD. For genotype association analysis, we tested additive, dominant, and recessive models, and all statistical models were covariate-adjusted with genetic ancestry scores, age at study entry, and sex.

Multiple-locus association and interaction analyses with AD

We examined the effects of multiple loci in each of the three genes on AD by assessing haplotype and gene–gene interaction analyses.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) and haplotype analysis: The LD matrices and blocks were determined for all samples using Haploview (v. 4.1) under the analysis criteria of Solid Spine of LD > 0.8 (Barrett et al. 2005). The haplotypes located within each LD block were inferred, and their statistical associations with AD were analyzed using HaploStats (v. 1.2.1) (http://mayoresearch.mayo.edu/mayo/research/biostat/schaid.cfm) following two approaches. As the LD between common tag SNPs and rare or low-frequency variants is low (Liu and Leal 2012), our first approach was to analyze associations of AD with haplotypes located within each LD block formed only by common alleles, excluding the low-frequency alleles located in the midst of haplotypes formed by the common variants (see Fig. 1). The second approach was to include the low-frequency alleles within the LD block to assess their contribution to the haplotypes formed by the common variants. We defined a ‘major haplotype’ as one with a frequency of >5 % in either the AD or the control sample. Bonferroni correction was used to calculate the corrected P value for haplotype analyses for individual haplotypes within each block.

Interactive effects of genotypes at multiple loci in HTR3A, HTR3B, and SLC6A4 on AD: We assessed the interactive effects of genotypes located at multiple loci within and among HTR3A, HTR3B, and SLC6A4 on AD susceptibility using a two-step statistical analysis. In the first step, interactive variant combinations were identified employing a Generalized Multifactor Dimensionality Reduction (GMDR beta version 0.7) (Lou et al. 2007). The GMDR identifies interactive variant combinations with the highest impact on phenotypic variation (high vs. low risk) using a score statistic calculated by accounting for covariates (age, sex, and genetic ancestry). First, an exhaustive computational search was performed for all possible two- to five-locus variant combination models using all 20 common variants. Then, the GMDR selected the best variant combination model(s) for a given order (i.e., two- to five-order combinations) on the basis of their P value derived from the nonparametric sign test, cross-validation consistency (CVC), and testing balanced accuracy (TBA) (Lou et al. 2007). All two- to five-locus variant combinations with sign test P values of <0.05 and CVC of 0.6 were then tested to gain empirical P values for their prediction accuracy using 106 permutations. Following identification of the best variant combinations, specific genotype combinations within the above-detected statistically significant SNP combinations were analyzed for their effects on AD.

Replication analyses using OZ-ALC-GWAS dataset

A total of 6,699 samples representing 2,313 families from the OZ-ALC-GWAS study were included in the replication analysis. A detailed description of the study can be found elsewhere (dbGaP Study Accession: phs000181.v1.p1) (Knopik et al. 2004; Lynskey et al. 2005). Among the individuals who had genotype calls, 892 had missing phenotype information, but all 2,313 families had at least one individual with the required data.

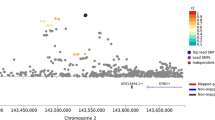

Imputation of non-genotyped SNP data

A total of 370,404 SNPs were genotyped in the OZ-ALC-GWAS study using the Illumina genotyping platform “HumanCNV370v1.” Because genotype information was available for only 7 of the 23 SNPs genotyped in the primary sample, we performed imputations using IMPUTE v. 2.2 (Howie et al. 2009) to generate genotype calls for the following ungenotyped SNPs: rs1062613, rs33940208, rs1176722, rs1176720, rs1176719, rs10160548, rs1150220, rs1176713, rs3758987, rs4938056, rs12270070, rs2276305, rs17116138, rs17614942, and rs1042173. We used pilot CEU haplotypes from the 1000 Genomes project in a 0.59-MB region covering both HTR3A and HTR3B on chromosome 11 and a 0.55-MB region covering SLC6A4 on chromosome 17 (Genomic built 36) as reference panels for imputing HTR3A/B and SLC6A4 SNPs, respectively.

5′-HTTLPR L/S allele predictions

Because the replication sample came from a GWAS study where only SNPs were assayed, we predicted the 5′-HTTLPR 44 bp insertion/deletion (L/S) variant in SLC6A4 using a two-SNP haplotype proxy consisting of rs2129785 and rs11867581, as described by Vinkhuyzen et al. (2011). Briefly, we constructed haplotypes for each individual using a tabulated haplotype phase for each individual in PLINK (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/purcell/plink/) (Purcell et al. 2007), using genotype data for SNPs rs2129785 and rs11867581 available in the OZ-Alc-GWAS data set. The haplotypes rs2129785:A–rs11867581:G and rs2129785:G–rs11867581:A were used as proxies for the 5′-HTTLPR L allele and haplotype rs2129785:A–rs11867581:A as proxy for the 5′-HTTLPR-S allele.

Interaction analysis

Following imputation tests, similar to the analyses in our primary sample, all 23 variants were analyzed for their single- and multiple-locus associations using software packages FBAT (Laird et al. 2000) and PLINK and for gene-by-gene interaction using the GMDR program as described above.

Results

Primary analysis

As mentioned in “Materials and methods”, the control sample had more female subjects than the AD sample, and for this reason, sex was included as a covariate in all analyses. Allele and genotype distributions for all HTR3A, HTR3B, and SLC6A4 variants in the control sample were similar to the frequencies reported in the HapMap data set (Supplementary Table 1). All HTR3A and SLC6A4 variants conformed to the HWE with the exception of SNP rs1176746 in HTR3B that significantly deviated from HWE (P = 9.0 × 10−4) in the control population, which thus was eliminated from subsequent association and interaction analysis. The overall genotype error rate was <1 %.

Single-locus analysis

The results from the allele and genotype association analyses for individual variants are presented in Table 1. Four common SNPs in HTR3B (i.e., rs3758987, rs4938056, rs3782025, and rs1672717) and the 5′-HTTLPR in SLC6A4 were marginally associated with AD. Of these, only the association of AD with rs3782025 in HTR3B remained significant after correcting for multiple comparisons with the SNPSpD program (Nyholt 2004). Among the three low-frequency SNPs examined, minor alleles of both rs33940208 in HTR3A and rs2276305 in HTR3B were significantly protective against AD with ORs of 0.212 (95 % CI 0.073, 0.616; P = 0.004) and of 0.261 (95 % CI 0.088, 0.777; P = 0.016), respectively.

Haplotype-based association analysis

We detected two LD blocks within HTR3A and two LD blocks within HTR3B (Fig. 1). In HTR3A, neither the haplotypes formed by the 6 common SNPs within Haploview-defined “LD Block 3,” nor the haplotypes formed by the four common SNPs within LD Block 4, were significantly associated with AD. Within LD Block 3, the low-frequency SNP rs33940208 and the common SNP rs1062613 located 71 bp upstream of rs33940208 formed a two-SNP minor haplotype (rs1062613:C–rs33940208:T) with a nominally significant protective effect against AD (haplotype score = −2.2259; P value for individual haplotype association analysis = 0.0260 and global P = 0.0347; OR = 0.3706; 95 % CI 0.1283, 1.0705).

In HTR3B, we detected a 5-SNP haplotype in Haploview-defined “LD Block 2” with a significant inverse association with AD (defined as haplotype 1 in Table 2). The LD Block 2 is located in and around four exons that are common to all mRNA isoforms of HTR3B. As shown in Fig. 1, two low-frequency SNPs (rs2276305 and rs17116138) also reside within the region covered by LD block 2.

To further examine the effect of two low-frequency SNPs, we re-analyzed haplotype 1 with the addition of major alleles of rs2276305 and rs17116138 (defined as haplotype 2 in Table 2). The haplotype consisting of minor allele of rs17116138 together with the other six alleles of haplotype 2 (rs12270070:G–rs1176744:A–rs2276305:G–rs17116138:G–rs2276307:A–rs3782025:A–rs1672717:A) was not significantly associated with AD; and the haplotype consisting of the minor allele of rs2276305 had a very low frequency (0.96 %) in our primary sample (haplotype 3 in Table 2). Thus, we were not able to assess whether haplotype 3 would confer a greater protective effect than haplotype 2 or the individual rs2276305:A allele.

Gene–gene interaction analysis

As shown in Table 3, we detected two four-variant interaction models with significant genetic interaction effects on AD, with an empirical P < 10−6, cross-validation consistency (CVC) of 10, and test accuracies (TA) >50 % based on 106 permutation tests. Because three of the four variants included in the two interaction models were identical, we combined the two four-variant models, and the resulting five-variant model was assessed for interactions with AD (third model in Table 3). The five-variant interaction model had a significant genetic interaction effect on AD, albeit with a smaller P value than the two four-variant models, possibly because of the smaller sample size for the five-variant interaction model. Subsequent to detecting the interaction models, we analyzed the “genotype combinations” within the two four-variant and the five-variant interaction models (see right-side panel of Table 3). As shown clearly in Table 3, persons with all three genotype combinations had greater risk of AD than did those with individual constituent genotypes: rs3782025:AG (OR 1.657; 95 % CI 1.187, 2.314), 5′-HTTLPR:LL/LS (OR 1.564; 95 % CI 1.058, 2.311), rs1176744:AG (OR 1.325; 95 % CI 0.955, 1.838), and rs1042173:TT/TG (OR 1.052; 95 % CI 0.681, 1.624). Thus, our results provide evidence for strong genetic interactions within the serotonergic system underlying AD.

Replication analysis in OZ-ALC-GWAS sample

The replication sample consisted of 1,739 DSM-IV-defined alcohol dependents, 4,068 control individuals, and 892 individuals without phenotypic data (affection status). Females were 37.72 % of the AD sample and 56.51 % of the control sample. The mean age (±SD) was 40.94 ± 10.75 in the ADs and 45.85 ± 8.29 in the control subjects. All statistically significant associations (P < 0.05) detected in the primary analyses were examined in the replication sample.

Imputation of missing SNPs and 5′-HTTLPR L/S allele predictions in OZ-ALC-GWAS study

Concordance rates for the 16 imputed SNPs using IMPUTE (v 2.2) ranged from 94 to 100 %, and proportions of missing genotypes were below 6 % for all imputations. The two proxy haplotypes for the 5′-HTTLPR:L allele, rs2129785:A–rs11867581:G, and rs2129785:G–rs11867581:A were present in the OZ-ALC-GWAS sample at frequencies of 0.436 and 0.110, respectively. The frequency of haplotype rs2129785:A–rs11867581:A, proxy for the 5′-HTTLPR:S allele, was 0.454. These estimated frequencies are similar to the L and S allele frequencies detected in the primary sample (0.546 vs. 0.550 for L and 0.454 vs. 0.451 for S).

Single-locus analysis

As shown in Table 4, two low-frequency alleles within HTR3A and HTR3B showed protective effects against AD in the OZ-ALC-GWAS sample: rs2276305:A (χ 2 = 7.224; P = 0.007) and rs33940208:T (χ 2 = 3.316; P = 0.0686). Genotype association analyses for rs2276305:AA/AG and rs33940208:TC/TT also revealed inverse associations with AD (Z = −2.555, P = 0.0106 for rs2276305:AA/AG and Z = −2.014, P = 0.0440 for rs33940208:TC/TT). None of the common variants that were significant (P = 0.05) at the single-locus level in the primary analyses was significant in the OZ-ALC-GWAS sample. However, the rs10160548:T allele, which was included in two interaction models presented in Table 3, was over-represented in ADs in the OZ-ALC-GWAS sample at the single-locus level (Z = 2.542; P = 0.0110).

Haplotype analysis

The two major haplotypes within HTR3B LD block 2 associated with AD in the primary sample (haplotypes 1 and 2 in Table 2) were not associated with AD in the OZ-ALC-GWAS sample. However, the rare haplotype detected in the primary sample (haplotype 3 in Table 2) consisting of the low-frequency allele rs2276305:A was present in the OZ-ALC-GWAS with a large enough sample (16 families; frequency = 0.007) to perform statistical analysis. The haplotype rs12270070:G–rs1176744:A–rs2276305:A–rs17116138:G–rs2276307:A–rs3782025:A–rs1672717:A showed a protective effect against AD with a Z score of −2.596 (P = 0.009).

Gene–gene interaction analysis

All three genotype combinations found to have an interactive effect on AD in the primary sample also had significant interactive effects on AD in the OZ-ALC-GWAS sample, with a Z value of 3.155–4.384 and P value of 0.0016–0.00001 (see Table 4 for details).

Discussion

In the present study, we detected and replicated the finding on the influence of three genotype combinations on the risk for AD and that of two low-frequency alleles protective against AD. The five interacting risk genotypes within SLC6A4 (5′-HTTLPR:LL/LS; rs1042173:TT/TG), HTR3A (rs10160548:GT/TT), and HTR3B (rs1176744:AC; rs3782025:AG) are variants previously shown to be associated with alcoholism or related intermediate phenotypes. As hypothesized, these interacting genotypes were linked to about a threefold greater risk of AD than their constituent individual genotypes. Importantly, allele-based functional differences for three of these five variants (i.e., SLC6A4: 5′-HTTLPR:LL/LS and rs1042173:TT/TG; HTR3B: rs1176744:AC) were demonstrated to be functional in earlier molecular studies. More specifically, alcoholics carrying the 5′-HTTLPR:L allele have lower serotonin transporter binding and reuptake activity than homozygous 5′-HTTLPR:S carriers according to an earlier study conducted by our group (Johnson et al. 2008). Similarly, the rs1042173:T allele was associated with lower expression of serotonin transporters (Lim et al. 2006; Seneviratne et al. 2009b). Thus, the 5′-HTTLPR:L and rs1042173:T alleles, in combination, may lead to a synaptic hyperserotonergic state. The third known functional variant included in the risk genotype combinations was the HTR3B non-synonymous SNP rs1176744 (A/C), which results in a tyrosine to serine change at the 129th amino acid residue in the extracellular N-terminal domain of 5-HT3B (Walstab et al. 2008) close to the 5-HT3AB interface (Krzywkowski et al. 2008). This amino acid substitution significantly increases 5-HT3AB ion channel open time, augmenting serotonergic signaling (Krzywkowski et al. 2008). In a recent study, Enoch et al. (2011) reported a higher risk of AD associated with high activity of the serine allele in African-American male alcoholics. Further, several other studies reported associations of the rs1176744 serine allele with other psychiatric disorders that often are co-morbid with AD in Caucasians (Frank et al. 2004; Hammer et al. 2009, 2012; Yamada et al. 2006). It should be noted that, unlike the study by Enoch et al., in our study, it was the heterozygous genotype of rs1176744 that contributed to all three risk genotype combinations and also showed a trend to risk at the single-locus level (OR = 1.325; 95 % CI 0.955, 1.838; P = 0.092). This suggests a molecular heterosis effect that could be race specific. From a structural point of view, our findings can be interpreted as co-expression of two 5-HT3B subunits in the same individual: one with the amino acid serine at position 129 and the other with tyrosine (“heterozygous” 5-HT3B subunits) leading to a higher risk of AD. In such a situation, it is hard to decipher which variant is more prevalent or the change of direction of serotonergic singling associated with the genotype. However, using cultured tsA-201 cells without any treatment, Krzywkowski et al. (2008) demonstrated that expression of “heterozygous” 5-HT3B subunits in the pentameric 5-HT3AB receptor complex would mimic the heterozygous carrier state. Expression of “heterozygous” 5-HT3B subunits resulted in an increase in the time the channel was open compared with 5-HT3AB complexes expressing two homozygous wild-type 5-HT3B subunits with the tyrosine residue (Hammer et al. 2009; Krzywkowski et al. 2008). Longer open time of the 5-HT3AB channels can lead to enhanced responsiveness of neurons to serotonin. This enhanced responsiveness associated with rs1176744:AG may be heightened by the greater availability of synaptic serotonin that is associated with the SLC6A4: 5′-HTTLPR:LL/LS and rs1042173:TT/TG genotypes.

The molecular mechanisms underlying allelic differences of the other two SNPs included in our risk genotype combinations, rs10160548 in HTR3A and rs3782025 in HTR3B, are not yet elucidated. Nevertheless, as intronic SNPs, it is possible that both rs3782025 and rs10160548 alter mRNA expression through alternate splicing. Furthermore, Ducci et al. (2009) reported an association of the rs3782025:A allele with a higher risk of AD + ASPD in Caucasians. Perhaps because of the inclusion of alcoholics with and without ASPD, our findings indicate an association of AD only with the heterozygous genotype of the rs3782025:A allele.

The second main finding of our study was the protective effects against AD shown by the two low-frequency synonymous variants rs33940208 in HTR3A exon 1 and rs2276305 in HTR3B exon 5. One important caveat to these findings, however, is that their significance values did not reach the threshold for multiple statistical tests. Nevertheless, these associations had medium to large effect sizes in the primary analysis (Cohen’s d for allelic associations of rs2276305:A and rs33940208:T with AD 0.74 and 0.86, respectively), which were validated by replication in the OZ-ALC-GWAS sample. To our knowledge, low-frequency variants with a protective effect on AD have not been reported previously in European populations. As both rs33940208 and rs2276305 are located within 100 bp of two well-characterized functional common variants (see Fig. 1), they may modulate the functionality of the common variants. The rs33940208:T allele was seen only in carriers of rs1062613:C: The C allele of rs1062613 has been associated with lower HTR3A expression (Kapeller et al. 2008) and the CC genotype with high anxiety and greater amygdala responsiveness to emotional stimuli in humans (Iidaka et al. 2005; Kilpatrick et al. 2011). As high anxiety is a risk factor for AD, one would expect the protective allele to be linked to the non-risk T allele. On the other hand, it is tempting to speculate that the protective effects of the rs33940208:T allele might offset reductions in transcription associated with the rs1062613:C allele, constituting a sub-population with greater expression than in the carriers of the rs1062613:C–rs33940208:G haplotype. Similarly, the other protective allele detected in our study, rs2276305:A, was seen only in carriers of the major allele of the common functional SNP rs1176744:A, which previously has been reported as the non-risk allele (Enoch et al. 2011). Taken together, these findings support the view that functionality attributed to common variants is in fact a consequence of “synthetic associations” arising from combined effects of multiple rare variants in their vicinity (Goldstein 2009). In fact, several examples of similar rare-common SNP modulating effects on other common disorders with high heritability rates such as AD have been reported (Raychaudhuri 2011). Thus, deep sequencing of HTR3A exon 1 and HTR3B exon 5 regions might help detect multi-variant modulating effects on the common functional SNPs rs1062613 and rs1176744.

The present study has two unique strengths. First, we analyzed an ethnically homogenous sample selected using self-reports of ethnicity and then subjected the sample to an additional “filtering” step based on their genetic ancestry using an ancestral marker panel. Second, we strengthened the reliability of our findings by replicating them in a larger independent family-based sample. Both the primary and the replication data set consisted of heavy drinkers who met the criteria for DSM-IV alcohol dependence, and the sex, age, and ethnic compositions were similar. Thus, we believe the two data sets were phenotypically similar. Also, the family-based structure of the replication data set provided us with enhanced statistical power, as risk or protective variants for common diseases segregate over several generations (Zhu and Xiong 2012). In addition to the strengths in the study design, a parallel study conducted recently by our group revealed that rs10160548 in HTR3A, rs1176744 in HTR3B, and 5-HTTLPR and rs1042173 in SLC6A4, which conferred risk for AD, also interacted significantly with each other to influence the risk of nicotine dependence in both Caucasians and African Americans (Yang et al. 2013). A minor concern about the present study is that most of the variants analyzed in the replication dataset were imputed or assessed by employing statistical algorithms rather than direct genotyping of the DNA samples. However, as the reliability rates were above 95 % for all imputations, we do not believe our findings would be affected by this fact.

In conclusion, our findings provide strong evidence for genetic variability underlying AD risk conferred by the interactive effects of SLC6A4, HTR3A, and HTR3B and low-frequency variants, especially some located close to common functional variants. Next-generation sequencing technologies may enable further refining of the identification of genetic variability within SLC6A4, HTR3A, and HTR3B that contributes to the risk of AD and related phenotypes.

References

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC

Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ (2005) Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 21:263–265

Bohn MJ, Babor TF, Kranzler HR (1995) The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation of a screening instrument for use in medical settings. J Stud Alcohol 56:423–432

Davies PA, Pistis M, Hanna MC, Peters JA, Lambert JJ, Hales TG, Kirkness EF (1999) The 5-HT3B subunit is a major determinant of serotonin-receptor function. Nature 397:359–363. doi:10.1038/16941

Ducci F, Enoch MA, Yuan Q, Shen PH, White KV, Hodgkinson C, Albaugh B, Virkkunen M, Goldman D (2009) HTR3B is associated with alcoholism with antisocial behavior and alpha EEG power—an intermediate phenotype for alcoholism and co-morbid behaviors. Alcohol 43:73–84. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.09.005

Enoch MA, Gorodetsky E, Hodgkinson C, Roy A, Goldman D (2011) Functional genetic variants that increase synaptic serotonin and 5-HT3 receptor sensitivity predict alcohol and drug dependence. Mol Psychiatry 16:1139–1146. doi:10.1038/mp.2010.94

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW (1994) Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, New York

Frank B, Niesler B, Nothen MM, Neidt H, Propping P, Bondy B, Rietschel M, Maier W, Albus M, Rappold G (2004) Investigation of the human serotonin receptor gene HTR3B in bipolar affective and schizophrenic patients. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 131B:1–5. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.30070

Goldstein DB (2009) Common genetic variation and human traits. N Engl J Med 360:1696–1698. doi:10.1056/NEJMp0806284

Hammer C, Kapeller J, Endele M, Fischer C, Hebebrand J, Hinney A, Friedel S, Gratacos M, Estivill X, Fichter M, Fernandez-Aranda F, Ehrlich S, Rappold G, Niesler B (2009) Functional variants of the serotonin receptor type 3A and B gene are associated with eating disorders. Pharmacogenet Genomics 19:790–799. doi:10.1097/FPC.0b013e32833132b3

Hammer C, Cichon S, Muhleisen TW, Haenisch B, Degenhardt F, Mattheisen M, Breuer R, Witt SH, Strohmaier J, Oruc L, Rivas F, Babadjanova G, Grigoroiu-Serbanescu M, Hauser J, Roth R, Rappold G, Rietschel M, Nothen MM, Niesler B (2012) Replication of functional serotonin receptor type 3A and B variants in bipolar affective disorder: a European multicenter study. Transl Psychiatry 2:e103. doi:10.1038/tp.2012.30

Hayes DJ, Greenshaw AJ (2011) 5-HT receptors and reward-related behaviour: a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 35:1419–1449. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.03.005

Hodge CW, Kelley SP, Bratt AM, Iller K, Schroeder JP, Besheer J (2004) 5-HT(3A) receptor subunit is required for 5-HT3 antagonist-induced reductions in alcohol drinking. Neuropsychopharmacology 29:1807–1813. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300498

Howie BN, Donnelly P, Marchini J (2009) A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet 5:e1000529. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000529

Iidaka T, Ozaki N, Matsumoto A, Nogawa J, Kinoshita Y, Suzuki T, Iwata N, Yamamoto Y, Okada T, Sadato N (2005) A variant C178T in the regulatory region of the serotonin receptor gene HTR3A modulates neural activation in the human amygdala. J Neurosci 25:6460–6466. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5261-04.2005

Johnson BA (2000) Serotonergic agents and alcoholism treatment: rebirth of the subtype concept—an hypothesis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 24:1597–1601

Johnson BA, Javors MA, Roache JD, Seneviratne C, Bergeson SE, Ait-Daoud N, Dawes MA, Ma JZ (2008) Can serotonin transporter genotype predict serotonergic function, chronicity, and severity of drinking? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 32:209–216. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.07.030

Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Seneviratne C, Roache JD, Javors MA, Wang XQ, Liu L, Penberthy JK, DiClemente CC, Li MD (2011) Pharmacogenetic approach at the serotonin transporter gene as a method of reducing the severity of alcohol drinking. Am J Psychiatry 168:265–275. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050755

Kapeller J, Houghton LA, Monnikes H, Walstab J, Moller D, Bonisch H, Burwinkel B, Autschbach F, Funke B, Lasitschka F, Gassler N, Fischer C, Whorwell PJ, Atkinson W, Fell C, Buchner KJ, Schmidtmann M, van der Voort I, Wisser AS, Berg T, Rappold G, Niesler B (2008) First evidence for an association of a functional variant in the microRNA-510 target site of the serotonin receptor-type 3E gene with diarrhea predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 17:2967–2977. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddn195

Kilpatrick LA, Labus JS, Coveleskie K, Hammer C, Rappold G, Tillisch K, Bueller JA, Suyenobu B, Jarcho JM, McRoberts JA, Niesler B, Mayer EA (2011) The HTR3A polymorphism c. −42C>T is associated with amygdala responsiveness in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 140:1943–1951. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.03.011

Knopik VS, Heath AC, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Slutske WS, Nelson EC, Statham D, Whitfield JB, Martin NG (2004) Genetic effects on alcohol dependence risk: re-evaluating the importance of psychiatric and other heritable risk factors. Psychol Med 34:1519–1530

Krzywkowski K, Davies PA, Feinberg-Zadek PL, Brauner-Osborne H, Jensen AA (2008) High-frequency HTR3B variant associated with major depression dramatically augments the signaling of the human 5-HT3AB receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:722–727. doi:10.1073/pnas.0708454105

Laird NM, Horvath S, Xu X (2000) Implementing a unified approach to family-based tests of association. Genet Epidemiol 19 Suppl 1: S36-42. doi:10.1002/1098-2272(2000)19:1+<::AID-GEPI6>3.0.CO;2-M

Li MD, Beuten J, Ma JZ, Payne TJ, Lou XY, Garcia V, Duenes AS, Crews KM, Elston RC (2005) Ethnic- and gender-specific association of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha4 subunit gene (CHRNA4) with nicotine dependence. Hum Mol Genet 14:1211–1219

Lim JE, Papp A, Pinsonneault J, Sadee W, Saffen D (2006) Allelic expression of serotonin transporter (SERT) mRNA in human pons: lack of correlation with the polymorphism SERTLPR. Mol Psychiatry 11:649–662. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001797

Liu DJ, Leal SM (2012) Estimating genetic effects and quantifying missing heritability explained by identified rare-variant associations. Am J Hum Genet 91:585–596. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.008

Lochner M, Lummis SC (2010) Agonists and antagonists bind to an A–A interface in the heteromeric 5-HT3AB receptor. Biophys J 98:1494–1502. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4313

Lou XY, Chen GB, Yan L, Ma JZ, Zhu J, Elston RC, Li MD (2007) A generalized combinatorial approach for detecting gene-by-gene and gene-by-environment interactions with application to nicotine dependence. Am J Hum Genet 80:1125–1137

Lovinger DM (1997) Serotonin’s role in alcohol’s effects on the brain. Alcohol Health Res World 21:114–120

Lynskey MT, Nelson EC, Neuman RJ, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, Knopik VS, Slutske W, Whitfield JB, Martin NG, Heath AC (2005) Limitations of DSM-IV operationalizations of alcohol abuse and dependence in a sample of Australian twins. Twin Res Hum Genet 8:574–584. doi:10.1375/183242705774860178

Mao X, Bigham AW, Mei R, Gutierrez G, Weiss KM, Brutsaert TD, Leon-Velarde F, Moore LG, Vargas E, McKeigue PM, Shriver MD, Parra EJ (2007) A genomewide admixture mapping panel for Hispanic/Latino populations. Am J Hum Genet 80:1171–1178. doi:10.1086/518564

Massoura AN, Dover TJ, Newman AS, Barnes NM (2011) The identification of N-glycosylated residues of the human 5-HT3B receptor subunit: importance for cell membrane expression. J Neurochem 116:975–983. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07129.x

Miyake A, Mochizuki S, Takemoto Y, Akuzawa S (1995) Molecular cloning of human 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptor: heterogeneity in distribution and function among species. Mol Pharmacol 48:407–416

Narahashi T, Kuriyama K, Illes P, Wirkner K, Fischer W, Muhlberg K, Scheibler P, Allgaier C, Minami K, Lovinger D, Lallemand F, Ward RJ, DeWitte P, Itatsu T, Takei Y, Oide H, Hirose M, Wang XE, Watanabe S, Tateyama M, Ochi R, Sato N (2001) Neuroreceptors and ion channels as targets of alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 25:182S–188S

Nyholt DR (2004) A simple correction for multiple testing for single-nucleotide polymorphisms in linkage disequilibrium with each other. Am J Hum Genet 74:765–769

Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC (2007) PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 81:559–575. doi:10.1086/519795

Raychaudhuri S (2011) Mapping rare and common causal alleles for complex human diseases. Cell 147:57–69. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.011

Seneviratne C, Ait-Daoud N, Ma JZ, Chen G, Johnson BA, Li MD (2009a) Susceptibility locus in neurokinin-1 receptor gene associated with alcohol dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology 34:2442–2449. doi:10.1038/npp.2009.65

Seneviratne C, Huang W, Ait-Daoud N, Li MD, Johnson BA (2009b) Characterization of a functional polymorphism in the 3′ UTR of SLC6A4 and its association with drinking intensity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 33:332–339. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00837.x

Sugita S, Shen KZ, North RA (1992) 5-Hydroxytryptamine is a fast excitatory transmitter at 5-HT3 receptors in rat amygdala. Neuron 8:199–203

Sun D, Ma JZ, Payne TJ, Li MD (2008) Beta-arrestins 1 and 2 are associated with nicotine dependence in European American smokers. Mol Psychiatry 13:398–406. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4002036

Sung KW, Engel SR, Allan AM, Lovinger DM (2000) 5-HT(3) receptor function and potentiation by alcohols in frontal cortex neurons from transgenic mice overexpressing the receptor. Neuropharmacology 39:2346–2351 (pii:S0028390800000642)

Vinkhuyzen AA, Dumenil T, Ryan L, Gordon SD, Henders AK, Madden PA, Heath AC, Montgomery GW, Martin NG, Wray NR (2011) Identification of tag haplotypes for 5HTTLPR for different genome-wide SNP platforms. Mol Psychiatry 16:1073–1075. doi:10.1038/mp.2011.68

Walstab J, Hammer C, Bonisch H, Rappold G, Niesler B (2008) Naturally occurring variants in the HTR3B gene significantly alter properties of human heteromeric 5-hydroxytryptamine-3A/B receptors. Pharmacogenet Genomics 18:793–802. doi:10.1097/FPC.0b013e3283050117

Yamada K, Hattori E, Iwayama Y, Ohnishi T, Ohba H, Toyota T, Takao H, Minabe Y, Nakatani N, Higuchi T, Detera-Wadleigh SD, Yoshikawa T (2006) Distinguishable haplotype blocks in the HTR3A and HTR3B region in the Japanese reveal evidence of association of HTR3B with female major depression. Biol Psychiatry 60:192–201. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.11.008

Yang Z, Seneviratne C, Wang S, Ma JZ, Payne TJ, Wang J, Li MD (2013) Serotonin transporter and receptor genes significantly impact nicotine dependence through genetic interactions in both European American and African American smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend 129:217–225. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.007

Zhou Q, Verdoorn TA, Lovinger DM (1998) Alcohols potentiate the function of 5-HT3 receptor-channels on NCB-20 neuroblastoma cells by favouring and stabilizing the open channel state. J Physiol 507(Pt 2):335–352

Zhu Y, Xiong M (2012) Family-based association studies for next-generation sequencing. Am J Hum Genet 90:1028–1045. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.022

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to MDL (Grants R01 DA012844 and 5 R01DA013783) and from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to BAJ (Grants 7 U10 AA011776-10, 1 N01 AA001016-000, 7 R01 AA010522-12, and 5 R01 AA012964-06) and NA-D (Grant 5 K23 AA000329-06). We are grateful to Dr. Shaolin Wang for his help with the statistical analyses. Additionally, we are thankful to the NIH GWAS data repository for providing us access to their dataset, through project 771 to Ming D. Li, under the title of “Genome-wide association analysis for addiction and type 2 diabetes”. GWAS of Alcohol Research using Australian twins and their families (OZ-ALC): Funding support for the [CIDR-OZ-ALC GWAS] was provided through the [Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR)] and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). [CIDR-OZ-ALC GWAS] is a genome-wide association study funded as part of NIAAA grant 5 R01 AA013320-04. Assistance with phenotype harmonization and genotype cleaning, as well as with general study coordination, was provided by the [CIDR-OZ-ALC GWAS]. Assistance with data cleaning was provided by the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Support for collection of datasets and samples was provided by the MARC: Risk Mechanisms in Alcoholism and Comorbidity (MARC; P60 AA011998-11). Funding support for genotyping, which was performed at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Inherited Disease Research, was provided by the NIH GEI (U01HG004438), the NIAAA, and the NIH contract “High throughput genotyping for studying the genetic contributions to human disease” (HHSN268200782096C).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seneviratne, C., Franklin, J., Beckett, K. et al. Association, interaction, and replication analysis of genes encoding serotonin transporter and 5-HT3 receptor subunits A and B in alcohol dependence. Hum Genet 132, 1165–1176 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-013-1319-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-013-1319-y