Abstract

Coproscopic examination of 505 dogs originating from the western or central part of Switzerland revealed the presence (prevalence data) of the following helminthes: Toxocara canis (7.1%), hookworms (6.9%), Trichuris vulpis (5.5%), Toxascaris leonina (1.3%), Taeniidae (1.3%), Capillaria spp. (0.8%), and Diphyllobothrium latum (0.4%). Potential risk factors for infection were identified by a questionnaire: dogs from rural areas significantly more often had hookworms and taeniid eggs in their feces when compared to urban family dogs. Access to small rodents, offal, and carrion was identified as risk factor for hookworm and Taeniidae, while feeding of fresh and uncooked meat did not result in higher prevalences for these helminths. A group of 111 dogs was treated every 3 months with a combined medication of pyrantel embonate, praziquantel, and febantel, and fecal samples were collected for coproscopy in monthly intervals. Despite treatment, the yearly incidence of T. canis was 32%, while hookworms, T. vulpis, Capillaria spp., and Taeniidae reached incidences ranging from 11 to 22%. Fifty-seven percent of the 111 dogs had helminth eggs in their feces at least once during the 1-year study period. This finding implicates that an infection risk with potential zoonotic pathogens cannot be ruled out for the dog owner despite regular deworming four times a year.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The close contact between dogs and humans harbors the risk of transmitting zoonotic agents. Thus, the ascarid worm Toxocara canis is considered to be one of the most frequent canine parasites that represents a considerable health risk especially for children. The nematode has a worldwide distribution, including countries with a high hygienic standard (Magnaval et al. 2001). In Switzerland, surveys on Toxocara infections in humans resulted in seroprevalences of 2.7–6.5% (Sturchler et al. 1986; Jacquier et al. 1991). Other zoonotic intestinal helminths in dogs prevalent in central Europe include the taeniid worms Echinococcus multilocularis and Echinococcus granulosus, the causative agents of alveolar and cystic echinococcosis, respectively (Eckert and Deplazes 2004). E. multilocularis is widespread in foxes of central Europe and increasingly includes dogs as a definitive host (Gottstein et al. 2001). Conversely, E. granulosus has practically disappeared in intermediate hosts in Switzerland and is only rarely found upon immigration or importation of infected dogs originating from endemic areas such as the Mediterranean basin (Eckert 1997). Other helminths that can be detected upon coprological analyses in Switzerland may affect the health status of the infected dogs, e.g., Trichuris vulpis or Ancylostoma caninum, whereas others exhibit only minor pathological potential, e.g., Uncinaria stenocephala, Capillaria spp., or Diphyllobothrium latum.

A major component for the spread of these parasites is the shedding of eggs via dog. Measures to control the infection risk for humans or to interrupt the cycle within the dog population therefore focus on (1) appropriate deworming strategies of the dogs and (2) minimization of the risk of fecal contamination in public places (e.g., playgrounds). For the latter, dog owners are requested to collect and remove the dog feces, whereas veterinarians have to advise dog owners about medication and frequency of anthelminthic treatments. In the present study, we used a questionnaire to document the deworming concept of dog owners and analyzed the efficacy of their treatment concept upon coprological examination of dogs while entering the study (prevalence). Subsequently, the incidence of infection was analyzed upon an anthelminthic treatment strategy followed for a period of 12 months.

Materials and methods

Dogs

A total of 505 dogs originating from the western or central part of Switzerland (cantons of Fribourg, Bern, and Zurich) participated in this study. The majority (n=470) was arbitrarily selected by veterinarians, with the owners’ consent. A general examination of the health status was carried out in the veterinary practice, and a fecal sample was rectally collected at the same time point. Thirty-five animals within this group were dairy farm dogs, and the dog owners were asked to collect fresh fecal samples by themselves.

Anthelminthic treatment of dogs

The veterinarians who participated in the present study selected 111 healthy dogs from the above mentioned group, and the owners complied to apply a defined anthelminthic treatment schedule for a period of 12 months. The dogs were perorally treated with a combination of pyrantel embonate, praziquantel, and febantel every 3 months (Drontal Plus, Bayer, Germany). The dosage was according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Coprological analyses

All fecal samples were tested by a standardized flotation method according to Rommel et al. (2000). This technique uses zinc chloride in a concentration of 44% (w/v) and is suitable for the coproscpic detection of helminth eggs exhibiting a specific weight of less than 1.2.

Fecal samples were further analyzed for the presence of intestinal Echinococcus sp. with an Echinococcus coproantigen ELISA (Deplazes et al. 1999). If taeniid eggs were found, these were further isolated and purified by a combination of sequential sieving and flotation in zinc chloride solution. Purified eggs were then subjected to an E. multilocularis-specific PCR (Mathis et al. 1996). For the present study, speciation will not be addressed for data evaluation, and we will refer only to the family of Taeniidae. We considered this acceptable by two reasons: (a) private clinics do not diagnostically discriminate taeniid eggs in view of speciation, and (b) praziquantel used in this study does identically affect all taeniid species known to occur in Swiss dogs.

All dogs that participated in the anthelminthic treatment study were followed up monthly in the veterinary practices. A clinical examination and collection of fecal samples was done as outlined above for entering the study.

Questionnaire

The dog owners had to fill out a questionnaire to provide information on the husbandry system [farm dog (including dogs from rural areas with access to farms), urban (family) dog], feeding habits, and anthelminthic treatment. Questionnaire parameters are outlined in “Results”.

Statistical analyses

Coprological results (positive/negative) and risk factor information collected from questionnaires were cross-tabulated and analyzed using a two-tailed Fisher’s exact test (FET; 2×2 tables) or chi-square test (CST, 2×j tables). To identify risk factors for overall helminth infestation, a multivariable logistic regression (LR) approach was used (NCSS 2004; http://www.ncss.com). All risk factors with P values less than 0.20 in the univariable analysis were jointly entered into the LR model. Subsequently, nonsignificant variables were removed as risk factors, together with all other factors of interest tested for their confounding effect on the remaining risk factors [more than 10% change in the odds ratio (OR) estimates]. Finally, two-way interactions between all remaining variables in the model were assessed for their statistical significance. In all statistics, P values less than 0.05 were considered significant, and those less than 0.01 were considered highly significant.

Results

First sample analysis (prevalence) and questionnaire

From 505 examined dogs (prevalence study), 99 (19.6%) had at least one helminthic species detectable in their feces. The most commonly found parasites were T. canis (6.9%), hookworms (6.9%), T. vulpis (5.5%), Toxascaris leonina (1.3%), Taeniidae (1.3%), Capillaria spp. (0.8%), and D. latum (0.4%). Multiple infections with four, three, or two different species were found in 16 dogs (Table 1). From seven dogs with taeniid eggs, one was positive only in the E. multilocularis coproantigen ELISA, and one was positive for both coproantigen ELISA and E. multilocularis-specific PCR.

Addressing a potential age-related distribution of the parasites, no respective findings could be shown. The different helminth species were found in all age categories, and a chi-square test did not reveal significant differences, neither for qualitative grouping (helminth positive/negative; P=0.5) nor for individual parasites (Table 2; due to the small numbers in several categories, the obtained values have to be interpreted with caution).

Based on the questionnaire, 26.9% of dogs that demonstrated the presence of helminth eggs in their feces were farm dogs, whereas the respective prevalence for dogs from urban areas was 16.6%. The difference between farm and urban dogs was significant (FET P=0.016). At the individual worm level, significant differences were observed for hookworms (P<0.01) and Taeniidae (P=0.015), while the difference between T. canis (P=0.82), T. leonina (P=0.68), T. vulpis (P=0.67), Capillaria spp. (P=0.66), and D. latum (P=1.0) was not significant.

Only a minority of the dogs (12.7%) did not receive any anthelminthic treatment, whereas 73.1% were treated once or twice a year. Additional treatments were given to 13.7% of the dogs every second month, while three dogs were treated monthly (0.5%; Table 3). The frequency of treatment did have little effect on the presence of helminth eggs in dog feces and only resulted in a significant reduction of hookworm eggs (CST P=0.018), while no significant difference was observed for other parasites (Fig. 1).

Prevalence of helminth eggs in Swiss dog feces in dependence of anthelminthic treatment (based on the questionnaire). Findings of the first coprological analysis (n=379). Frequency of treatment based on the questionnaire: no treatment (black bar), once to twice a year (open bar), more than twice a year (grey bar). Significant differences are marked with an asterisk

The dog owners had to categorize the feeding behaviors of their dogs. Of the 398 dogs, 78 (19.6%) regularly received fresh uncooked meat. The prevalence of helminths in such dogs (26.9%) was not significantly higher than in dogs receiving uniquely canned or cooked food (16.6%; FET P=0.27). The FET was also performed for individual helminthes and gave no P values lower than 0.1 for T. canis. (P=0.119), T. leonina (P=1.0), hookworms (P=0.823), T. vulpis (P=0.613), Capillaria spp. (P=0.584), D. latum (1.0), and Taeniidae (P=0.335).

According to the dog owners, 60.9% of the dogs were not permanently under control and had the possibility to hunt small rodents, had access to offal and carrion, or were eating garbage. Among these dogs, the prevalence of helminth eggs was 25.1%. The prevalence in “controlled” dogs was 14.1%, which is significantly lower (FET P=0.008). At the individual helminth level, only hookworm eggs (FET P=0.009) were significantly more often detected in “uncontrolled” dogs, while no difference was found for T. canis (P=0.140), T. leonina (P=0.411), T. vulpis (P=0.413), Capillaria spp. (P=0.160), D. latum (0.152), and Taeniidae (P=0.085).

In the final multivariable LR model, deworming (coded yes/no) was identified as a protective factor for detection of helminth eggs in dog feces [OR 0.52, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.26–1.04], while uptake of offal, carrion, or garbage was a risk factor (OR 2.12, 95% CI 1.08–4.14). The variable farm dog remained in the model as a confounder but was not significantly associated with the helminth status (P=0.22).

Effects of regular anthelminthic treatment

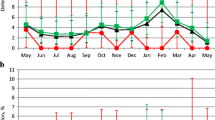

A group of 111 dogs was treated every 3 months with combined medication of pyrantel embonate, praziquantel, and febantel. The yearly incidence of T. canis, hookworms, T. vulpis, Capillaria spp., and Taeniidae was between 11 and 32% (Fig. 2). Sixty-three dogs (56.8%) had helminth eggs in their feces at least once a year. The treatment did not result in a significant reduction of egg secretion, neither for nematodes nor for cestodes, as determined by chi-square test. Fig. 3 shows the prevalence of the individual parasites detected 1, 2, and 3 months after treatment (mean prevalence of four samples collected during the 1-year period).

Prevalence of helminth eggs in Swiss dog feces after treatment every 3 months with pyrantel embonate, praziquantel, and febantel (n=111). Samples were collected in monthly intervals for 1 year. Bars represent the percentage of positive dogs for the specified parasite: 1 month (black bar), 2 months (open bar), and 3 months (grey bar) after drug application. The respective coprological specimen was collected at the same time point when the next treatment was administered

Discussion

Coprological analysis of samples from 505 healthy dogs provided an insight into the distribution and occurrence of intestinal parasites in Swiss dogs. These findings show similar parasite patterns as described by others, with the exception of lacking lungworm (Deplazes et al. 1995; Barutzki and Schaper 2003; Epe et al. 2004). In the present study, the funnel technique according to Baermann–Wetzel, which is specific for detection of viable larvae, was not used. According to other authors, T. canis and hookworms are the most commonly found helminths in dogs. However, the parasite prevalence was lower in our study than in samples obtained from dogs at the veterinary hospital for routine diagnosis or samples collected from stray dogs (Deplazes et al. 1995; Barutzki and Schaper 2003). Interestingly, there was no age-related distribution of the parasites. Especially T. canis, which is described as typical parasite of pups, was not found in animals of age less than 1 year (Scothorn et al. 1965). This may be partially explained by optimal anthelminthic treatment that dog owners apply especially in the early phase of life, as all dogs in this age segment received at least one treatment. Furthermore, the low number of pups included in the study may lead to an underestimation of parasite detection and makes a statistical analysis rather difficult. It was shown that treatment had a slight positive effect in reducing the detection rate of helminthes, which was even significant for hookworms. However, more frequent treatment did not necessarily result in a further decrease of parasite detection. A quantification of parasitic stages in the feces was not done, nor was information available on the active substance used and the form of application. Interpretation on partial effects and dosage problems was therefore not possible.

Additional information became available from the controlled treatment with a combined application of pyrantel embonate, praziquantel, and febantel every 3 months. Surprisingly, despite regular treatment, the yearly incidence of T. canis was 32%, while hookworms, T. vulpis., Capillaria spp., and taeniid eggs were detected in 11–22% of the dogs at least once a year. As the prepatency period of the mentioned parasites is less than 3 months, it can be assumed that reinfection most likely occurred. However, a comparison of parasitological findings 1, 2, and 3 months after treatment did not result in significant differences for individual parasites, although we observed a tendency toward a lower parasite detection rate in the first month compared to the subsequent months (T. canis, hookworms, and T. vulpis). It cannot be excluded that treatment does not completely eliminate the parasites, and helminth eggs still may be detected in fecal samples. The used substances are described to have an efficacy of 92–98% against the parasites described in our study (Lloyd and Gemmell 1992; Prelezov and Bauer 2003; Mehlhorn et al. 2003). As every treatment was done under controlled conditions by the veterinarian, an inappropriate application or wrong dosage is very unlikely.

The feeding of fresh uncooked meat was not identified as a risk factor for infection with intestinal helminths, while the uncontrolled feeding of rodents, offal, or carrion was identified to be responsible for the appearance of hookworm and taeniid eggs. It is probable that especially small rodents serve as intermediate (Taenia sp. and Echinococcus sp.) or paratenic hosts (hookworms and T. canis). Twenty dogs shed parasites which must have originated from ingestion of foreign feces as they were not dog specific (mainly Eimeria spp. oocysts; data not shown). With the exception of one, all were defined as “uncontrolled feeder.” Coprophagia is an important factor that should not be neglected when performing and interpreting parasitological analyses. Several parasite stages that are only passing the intestinal tract may not be easily distinguished from dog-specific parasites (e.g., Capillaria spp. or taeniid eggs from cat feces). Furthermore, it may be possible that the prevalence of canine parasites is overestimated due to coprophagia of fox feces, which is abundant in rural as well as urban areas (e.g., taeniid eggs, Toxocara, hookworms). This hypothesis is favored by the fact that coprophagia was identified as a significant risk factor for the presence of hookworm (FET P=0.009) and taeniid eggs in dog feces (P=0.002).

Several parasites detected in the dog feces are of zoonotic potential. Especially T. canis (Glickman and Shofer 1987) and E. multilocularis (Deplazes and Eckert 2001), the latter was identified in one dog in the prevalence study by antigen testing and PCR, can cause significant health problems in humans.

The present findings show that despite regular treatment and efficient drug components four times a year, only 39 of 111 dogs did not have any helminth stages in all fecal samples, and helminths may be present in almost two third of the dog population. Veterinarians should therefore inform dog owners that even after deworming, dogs may be a potential infection source for humans.

References

Barutzki D, Schaper R (2003) Endoparasites in dogs and cats in Germany 1999–2002. Parasitol Res 90 (Suppl 3):S148–S150

Deplazes P, Eckert J (2001) Veterinary aspects of alveolar echinococcosis—a zoonosis of public health significance. Vet Parasitol 98:65–87

Deplazes P, Guscetti F, Wunderlin E, Bucklar H, Skaggs J, Wolff K (1995) Endoparasite infection in stray and abandoned dogs in southern Switzerland. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd 137:172–179

Deplazes P, Alther P, Tanner I, Thompson RC, Eckert J (1999) Echinococcus multilocularis coproantigen detection by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in fox, dog, and cat populations. J Parasitol 85:115–121

Eckert J (1997) Epidemiology of Echinococcus multilocularis and E. granulosus in central Europe. Parassitologia 39:337–344

Eckert J, Deplazes P (2004) Biological, epidemiological, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis, a zoonosis of increasing concern. Clin Microbiol Rev 17:107–135

Epe C, Coati N, Schnieder T (2004) Results of parasitological examinations of faecal samples from horses, ruminants, pigs, dogs, cats, hedgehogs and rabbits between 1998 and 2002. Dtsch Tierarztl Wochenschr 111:243–247

Gottstein B, Saucy F, Deplazes P, Reichen J, Demierre G, Busato A, Zuercher C, Pugin P (2001) Is high prevalence of Echinococcus multilocularis in wild and domestic animals associated with disease incidence in humans? Emerg Infect Dis 7:408–412

Glickman LT, Shofer FS (1987) Zoonotic visceral and ocular larva migrans. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 17:39–53

Jacquier P, Gottstein B, Stingelin Y, Eckert J (1991) Immunodiagnosis of toxocarosis in humans: evaluation of a new enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit. J Clin Microbiol 29:1831–1835

Lloyd S, Gemmell MA (1992) Efficacy of a drug combination of praziquantel, pyrantel embonate, and febantel against helminth infections in dogs. Am J Vet Res 53:2272–2273

Magnaval JF, Glickman LT, Dorchies P, Morassin B (2001) Highlights of human toxocariasis. Korean J Parasitol 39:1–11

Mathis A, Deplazes P, Eckert J (1996) An improved test system for PCR-based specific detection of Echinococcus multilocularis eggs. J Helminthol 70:219–222

Mehlhorn H, Hanser E, Harder A, Hansen O, Mencke N, Schaper R (2003) Synergistic effects of pyrantel and the febantel metabolite fenbendazole on adult Toxocara canis. Parasitol Res 90 (Suppl 3):S151–S153

Prelezov PN, Bauer C (2003) Comparative efficacy of flubendazole chewable tablets and a tablet combination of febantel, pyrantel embonate and praziquantel against Trichuris vulpis in experimentally infected dogs. Dtsch Tierarztl Wochenschr 110:419–421

Rommel M, Eckert J, Kutzer E, Körting W, Schnieder T (2000) Veterinärmedizinische Parasitologie, 5th edn. Blackwell, Berlin

Scothorn MW, Koutz FR, Groves HF (1965) Prenatal Toxocara canis infection in pups. J Am Vet Med Assoc 146:45–48

Sturchler D, Bruppacher R, Speiser F (1986) Epidemiological aspects of toxocariasis in Switzerland. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 116:1088–1093

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to U. Brönnimann and P. Stünzi for excellent technical assistance. Furthermore, the collection of samples from and the clinical examination of the dogs by the veterinarians is greatly acknowledged. We are also thankful to all the dog owners who were willing to participate in this study. This project was financed by the Swiss Federal Veterinary Office (BVET). Additional support was obtained from the EU project no. BBW 00.0498.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

H. Sager and Ch. Steiner Moret contributed equally to the present work. This work is part of the doctoral thesis of Ch. Steiner Moret

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sager, H., Moret, C.S., Grimm, F. et al. Coprological study on intestinal helminths in Swiss dogs: temporal aspects of anthelminthic treatment. Parasitol Res 98, 333–338 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-005-0093-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-005-0093-8