Abstract

Purpose

We sought to characterize the clinical features and management of patients diagnosed as Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (KHE) without cutaneous involvement.

Methods

The electronic patient chats at six Triple A hospitals in China were searched to find all patient diagnoses with KHE without cutaneous involvement.

Results

Of 30 patients (mean age at diagnosis, 55.6 months), 17 (56.7%) were male. Fourteen (46.7%) patients were associated with Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon (KMP). Patients with KMP were significantly more likely to have lesions involving truck compared to patients without KMP (odds ratio 10.000; 95% confidence interval 1.641–60.921; P = 0.011). Other common complication included severe anemia and decreased range of motion. In the majority of cases (93.3%), the lesions were highly infiltrative and locally invasive with ill-defined margins. Histological examination was required in all patients without KMP for precise diagnosis. In all, 16 (53.3%) patients received corticosteroid treatment, 19 (63.3%) received oral sirolimus treatment, 7 (23.3%) received intravenous vincristine, and 5 (16.7%) patients used propranolol. Patients had varied responses to conventional drugs, whereas all patients receiving sirolimus treatment had better response. In all, three patients (10%) died of disease, all presented with KMP. Feature of these recalcitrant cases (death) included young age, visceral location, extensive involvement, and lack of improvement with high-dose corticosteroids.

Conclusions

Our study clearly demonstrated that KHE without cutaneous involvement could be associated with important complication, which might result in death or severe morbidity. Increased awareness of KHE without cutaneous involvement is required for early diagnosis and aggressive therapy in an attempt to prevent complication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (KHE) is a rare vascular neoplasm occurring primarily in infancy or early childhood. KHE has intermediate malignant characteristics and shows locally aggressive and infiltrative growth, with a low tendency to resolve spontaneously. The annual incidence of KHE has been estimated at 0.071 per 100,000 children (Croteau et al. 2013). KHEs were slightly more common among male than female patients (Ji et al. 2018). The tumors often associated with a life-threatening thrombocytopenia and consumptive coagulopathy known as Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon (KMP). KMP was first described by Kasabach and Merritt in 1940 as a complication of ‘capillary hemangioma’ (Kasabach and Merritt 1940). It is now clear that KMP occurs uniquely with KHE and tufted angioma, not with infantile hemangiomas. In addition, KMP usually associated with severe anemia resulting from intralesional hemorrhage (Ji et al. 2018). KMP is typically associated with more aggressive lesions and poorer outcomes, with a mortality rate estimated at 10–30%. The mortality rate in patients with KHE is strongly influenced by the clinical features, associated complications, speed of diagnosis, and initiation of appropriate treatment (Drolet et al. 2013; O’Rafferty et al. 2015).

KHE has varied locations. Although most KHE presented as visible cutaneous lesions, more than 10% of cases did not have cutaneous involvement (Croteau et al. 2013; Ji et al. 2018). The non-cutaneous sites included retroperitoneum, abdomen, mediastinum, muscle, bone and articular regions. Intrathoracic and retroperitoneal KHEs have an even worse prognosis (Mahajan et al. 2017). In the present study, we conducted a retrospective study to analyze the general clinical characteristics of patients followed up as KHE at our institutions who had no skin involvement in a period of 12 years.

Methods

Data collection

We conducted a retrospective review through the pathology database and medical records dating from January 2006 and January 2018. Data were collected on patients who were diagnosed with KHE without cutaneous involvement. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of West China Hospital of Sichuan University, the study site of the principal investigator, and by the local institution review boards at each participating site. All procedures followed the research protocols approved by West China Hospital of Sichuan University and Sichuan University and wwere conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their parents.

The inclusion criteria were the clinical presentation of vascular tumor with clinical feature of KHE without cutaneous involvement. Diagnosis of KHE was based on clinical presentation/feature, imaging study and/or histological data, according to the findings published previously (Enjolras et al. 1997; Sarkar et al. 1997). Patients with clinical and radiologic features of KHE and associated KMP onset were considered to have KHE even though they did not have histologic confirmation. Patients were excluded if they had insufficient data.

The medical charts, including demographics, clinical presentations, laboratory results, imaging studies, pathological findings, treatment strategies, follow-up examinations and outcomes, were obtained. In addition to obtaining ultrasound (US) results, the available radiology database was queried for computer tomography (CT) scans and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The maximum diameter of the lesion was measured and documented. The depth of the lesion infiltration was determined by radiographic studies. Homogeneous and heterogeneous were visually evaluated and documented based on the texture of the lesions. The density and signal intensity of KHE lesion were documented as hypo, iso and hyper, respectively, compared with those of the muscle. The degree of enhancement was also assessed on CT and/or MRIs. If the degree of enhancement was similar to that of vessels, it was considered intense.

Definition

According to previous studies, we designated KHE without cutaneous involvement as deep KHE that located in the mediastinum, retroperitoneum, internal organs, bones and joints (Ji et al. 2018). KMP was defined as a platelet count of less than 100 × 109/L, with or without consumptive coagulopathy and hypofibrinogenemia (Croteau et al. 2013). Severe acquired hypofibrinogenemia was defined as a fibrinogen level less than 1.0 g/L. Severe anemia was defined as a hemoglobin concentration less than 80 g/L. Decreased range of motion (ROM) was defined as ≥ 10° of extension loss, flexion < 120°, or both.

Treatment response was classified as success (better), stabilization (no change) and worse. Based on previous studies, a successful treatment response was defined as an improvement in the patient’s complications, the restoration of hematologic parameters, and a reduction in KHE volume (Ji et al. 2017). Restoration of hematologic parameters was defined as a platelet count > 100 × 109/L, fibrinogen > 1.0 g/L and hemoglobin > 80.0 g/L. CT or MRI scan was used to document a reduction in the size of the tumor by objective measurement.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as the means with ranges or the median with the interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and as frequencies with percentages for qualitative variables. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were assessed for potential associations with developing KMP. Pearson’s Chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test were used to analyze of categorical variables. Student’s t test was used to analyze continuous variables where appropriate. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 22.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Only patients with deep lesions locating in the mediastinum, retroperitoneum, internal organs, bones, muscles and joints were included. A total of 30 patients presented with deep KHE, and 13 of them were female and 17 were males (Table 1). Regarding admission sources, 25 (83.3%) patients were transferred from other hospitals. The demographic features of the patients and the distribution of lesions are shown in Table 1. The median age at discovery of the tumor lesion was 6.0 months (IQR 2.0–29.0 months). The median age at diagnosis of KHE was 12.5 months (IQR 2.9–37.5 months).

Of the 30 patients, trunk was the most common anatomic locations of the lesions. Eight and three patients had lesions involving retroperitoneum and mediastinum, respectively (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2). Three (10.0%) patients had lesions that extended into more than one anatomic region. Three patients had multifocal lesions, all involving vertebrae bodies (Fig. 1). Twelve patients had lesions confining to the bone–joint–muscle area.

A 5.5-year-old boy showed low backache with claudication for 1.5 years. His parents complained that he was unwilling to walk. Sagittal (a), coronal (b), and horizontal (c) T2-weighted MRI reveal hyperintense lesions infiltrating vertebrae from L4 and L5, right ilium and femur. There are observable signal alterations paralleling the right paravertebral area

KMP and other complications

Routine blood parameters and coagulation function were monitored regularly. In total, 14 (46.7%) patients had confirmed KMP. No significant sex distribution was observed between patients with or without KMP [odds ratio (OR) 1.667; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.388–7.153; P = 0.491]. Patients with KMP were younger on age at discovery of tumor (mean 4.3 months) and age at diagnosis of KHE (mean 5.0 months) than patients without KMP (P < 0.05). The average time interval between the presentation of KMP and the diagnosis of the KHE was 2.5 months (range 0.0–12.6). Patients with KMP were significant more likely to have lesions involving truck compared to patients without KMP (OR 10.000; 95% CI 1.641–60.921; P = 0.011).

Severe anemia was common in patients with KMP. Other KMP-related complications include pericardial effusion, pleural effusion and active organ bleeding. Fifteen patients (46.9%) were considered to have decreased ROM with or without chronic pain related to KHE. In ten cases, decreased ROM was evident before the initial assessment. Patient #24 had unexplained profound thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy for 12 months. The tumor mass has not been identified until the patient developed progressively decreased ROM of his right hip joint. The remaining five patients did not have decreased ROM at the time of initial assessment, but decreased ROM occurred thereafter.

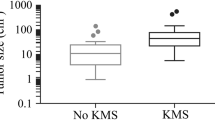

Imaging findings

Initial diagnostic management included ultrasound (US), computer tomography (CT) scans and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Pre-treated CT and/or MRI were available for all patients. Of the entire cohort, the maximum diameter in individual patient ranged from 2.0 cm to 12.0 cm, with a mean size of 4.7 cm. Patients with KMP had an average lesion size (mean 5.6 cm) that was bigger than that of patients without KMP (mean 3.9 cm) (OR 5.607; CI 4.120–7.095; P < 0.001).

The classical appearance of KHE on US is that of a homogenous, ill-defined mass. On unenhanced CT scans, the majority KHE exhibited homogeneous iso-attenuation with adjacent muscle. All cases exhibited heterogeneous notable enhancement after administration of contrast media. On MRI, KHE lesions showed hypo-/isointense signal on T1-weighted imaging relative to muscle, and usually infiltrated multiple tissue planes. On T2-weighted imaging, KHE typically demonstrated heterogeneous hyperintense masses. In the majority of cases (28/30), the mass extends into surrounding vital organ, abdominal spaces, or involving the joints, bones, muscles, and subcutaneous tissues, with ill-defined margins. Only two masses in the pancreas showed well-defined margins (Wang et al. 2017).

In all, 17 cases (56.7%) were found with erosion or remodeling of adjacent joint and/or bone. The bone marrow signal alterations and/or cortical irregularities were common in these cases. Hemorrhage and calcifications were noted in one and two cases, respectively.

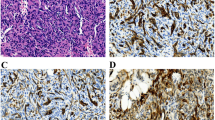

Pathological findings

Biopsies were available in 28 of 30 patients (except patient #24 and #30). Ten specimens were taken during the active phase of KMP. All specimens had the characteristic pathological features of KHE. On light microscopy, the infiltrating nodules were composed of small round vascular channels lined by spindle endothelial cells. Deposition of microthrombi and hemosiderin was observed in ten specimens in the presence of KMP. Immunohistiochemical examinations of all specimens were positive for vascular endothelial markers CD34/CD31 (Fig. 2) and lymphatic endothelial marker D2-40 and Prox-1, but negative for GLUT-1 and HHV-8. Three patients had both early and late biopsy. In three late biopsies of residual lesions, the specimens demonstrated lymphatic spaces and dense fibrosis.

Photomicrographs of kaposiform hemangioendothelioma involving ileum and mesentery. There are nodular vascular proliferations extending deeply throughout the intestinal wall (a hematoxylin and eosin staining, × 40). Closely packed, spindle tumor cells with occasional slit-like or round lumen in a pattern resembling Kaposi sarcoma can be seen at higher magnification (hematoxylin and eosin staining, b × 100; and c × 200)

Treatment

The management regimens were variable (Table 2). Treatments given most commonly were corticosteroids and sirolimus. In all, 16 (53.3%) patients received corticosteroids (orally, intravenously, or intramuscularly administered). Corticosteroid monotherapy typically led to varied degree of improvement at the beginning of treatment, but KMP usually recurred or worsened when the treatment was continuing. In all, three patients died, with all deaths being KMP related. These patients were younger than 6 months at the time of presentation of KMP. The dosages of prednisone or prednisolone in these patients were high as 5–6 mg/kg/day. One patient had huge KHE lesion involving the mediastinum. The patients suffered severe respiratory distress and died from a fatal cardiac arrest. The second patient had KHE involving pelvic cavity. The tumor infiltrated multiple internal organs including bladder and ureter, and lad to severe bilateral hydronephrosis. The third patient had a retroperitoneal KHE. The latter two patients died as a direct result of severe, tumor-related thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy.

Sirolimus plus corticosteroid was the most common treatment regimen for KHE with KMP since 2011. This treatment regimen was effective in controlling the growth of KHE and providing a rapid improvement in hematopoietic parameters (Fig. 3). Parameter for tapering corticosteroids included stabilization or normalization of platelet count.

Deep KHE with KMP involving trunk and right thigh. A 1.3-year-old boy had unexplained profound thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy for 12.6 months. At 13 months of age, the patient demonstrated progressively decreased right hip ROM. Coronal T2-weighted MRI revealed a mixed lesion infiltrating the pelvic cavity, proximal femur and pelvis (a). His platelet count was 6 × 109/L and fibrinogen was 1.30 g/L. The patient received sirolimus in combination with a short-term administration of prednisolone, followed by 10.0 months of sirolimus monotherapy. Prednisolone was successfully tapered and discontinued at 4 and 8 weeks, respectively. At 2.3 years of age, MRI showed obvious tumor shrinkage (b)

For patients without KMP, treatment given most commonly was sirolimus monotherapy (12/16). Conventional drugs, including corticosteroid and propranolol, were less effective than sirolimus in improving the associated musculoskeletal complications (decreased ROM and chronic pain) (Fig. 4).

Deep KHE without KMP in a 5-year-old boy. a Physical examination demonstrated swelling and genu valgum of the right knee. b Coronal T2-weighted MRI revealed an ill-defined, enhanced mass without definite solidity. The mass involved the metaphysic and epiphysis of the right femur, proximal tibia, and subcutaneous tissue. The patient received 12.0 months of sirolimus monotherapy. c Clinical photographs at 12 months after the introduction of sirolimus treatment. d MRI at 12.0 months of sirolimus treatment demonstrated a marked decrease in the size of the mass

Nearly complete surgical resection was feasible and offered definitive cure in one patient with KHE involving small bowel (patient #27). Partial resection has been performed in another three patients with KMP. In patient #18 who had retroperitoneal lesion, although surgical excision improved the associated KMP, the patient suffered from rapidly progressing scoliosis despite prolonged corticosteroid treatment, requiring a switch to sirolimus.

Discussion

KHEs without cutaneous involvement present a unique diagnostic and treatment challenge to clinicians due to their heterogeneous clinical manifestation. Previously, several case reports have described the clinical features and management of KHE without cutaneous involvement (Iwami et al. 2006; Rodriguez et al. 2009; San et al. 2008). Our study revealed a wide range of clinical characteristics regarding location and depth of tissue involvement, as well as associated complications, imaging features and pathological features in addition to previously described findings. Increased knowledge of clinical characteristics associated with KHE may be helpful in determining the appropriate diagnosis and avoiding the mortality and long-term morbidity.

In our recent study, we categorized KHEs into three distinct morphological types: superficial, mixed (cutaneous lesions with deep infiltration) and deep (lesions without cutaneous involvement). We found that 12.3% of patients lacked cutaneous involvement. KMP was identified in 69.9% of patients (Ji et al. 2018). We revealed that the greatest risk factor for KMP was young patients with large mixed lesion. These mixed lesions infiltrated deeply into muscle, bone, joint, or with mediastinal or retroperitoneal involvement. Interestingly, deep lesion was not a significant factor for KMP in this cohort (Ji et al. 2018). However, deep KHEs, especially visceral KHEs are usually undetectable, easily missed clinically and generally associated with a high mortality.

The diagnosis of visceral KHEs can be difficult especially when there are no cutaneous clues. Clinically, deep KHE with KMP should be considered in patients presenting with an unexplained thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy, especially in cases coexisting with purpura and anemia (Hall 2001). CT or MRI scan of the abdomen and chest should be recommended for such patients. The co-existence of a vascular mass with prominent thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy, including hypofibrinogenemia, can make the diagnosis of KHE relatively straightforward. In this regard, laboratory evaluation is essential for the diagnosis. In addition, the infiltrative growth pattern has been reported as one of the unique characteristics of KHEs, rendering there lesions distinct from benign vascular tumors, such as infantile hemangiomas (Hu and Zhou 2018; Ryu et al. 2017). In patients with clinical features that were consistent with KHE with KMP, a histopathological examination was not necessary to confirm diagnosis (Drolet et al. 2013). In the present study, two patients with deep KHE and KMP did not undergo incisional or punch biopsy during diagnostic workup.

Three cases of KHE with KMP involving in the mediastinum were reported in the present study, including one case with multifocal KHE. The mediastinal KHEs can lead to respiratory problem. In addition, the infiltrative nature of the lesion can result in pericardia and pleural effusion (Iwami et al. 2006). The differential diagnosis of such a heterogeneous presentation includes malignancy, Gorham–Stout disease, and generalized lymphatic anomaly (GLA). Remarkably, kaposiform lymphangiomatosis (KLA), a more aggressive form of GLA, presents as an intrathoracic disease with worsening respiratory symptoms and hemorrhagic pericardia and pleural effusion. Patients with KLA can be associated with thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy, which is similar to KMP seen in patients with KHE (Croteau et al. 2014). However, KLA is multifocal or diffuse and often has extrathoracic involvement (retroperitoneum and spleen). In addition, the thrombocytopenia in KLA is generally less severe than that observed in KMP (Fernandes et al. 2015). Nonetheless, pathological evaluation is crucial in making the differential diagnosis of KHE and KLA and often requires special immunostaining investigations.

Although the presence of KMP in young children with vascular lesions can be highly suggestive of KHE, KHE can occur without KMP in 29–43% of cases (Croteau et al. 2013; Enjolras et al. 2000; Ji et al. 2018; Lyons et al. 2004; Ryan et al. 2010). In patients with clinical features that are not typical of KHE, it is necessary to exclude the possibility of other diseases. Definitive preoperative differential diagnosis between deep KHE and a malignant tumor is particularly challenging in patients with multilevel spine involvement without KMP (Lisle et al. 2009). Even in patients with deep KHE involving extremities, definitive diagnosis is often delayed because of slow disease progression and the constellation of symptoms. For such cases, a complete diagnostic workup should include laboratory tests, imaging studies and pathological evaluations.

Direct extension from mediastinal and retroperitoneal to pancreas, mesentery and pericardium has been reported (Croteau et al. 2013; Ji et al. 2018). In most cases, the total resection of tumor was unviable treatment option due to infiltrative feature of the deep KHE. In the present study, the girl (patients #18) suffered progressive scoliosis after partial resection of her retroperitoneal lesion, highlights the potential of these tumors to cause significant bony deformation despite the resolution of KMP.

Previously, vincristine has been advocated for first-line treatment of KHE. However, many patients failed to respond to vincristine (Liu et al. 2016; Rodriguez et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2015a, b). Corticosteroid is recommended as another first-line therapy because of its success in rapidly normalizing platelet counts, although many patients experienced a relapse of KMP associated with an enlargement of the lesion (Croteau et al. 2013; Tlougan et al. 2013). Successful use of vincristine plus ticlopidine and aspirin plus ticlopidine has also been reported in some cases (Fernandez-Pineda et al. 2010, 2013).

Recently, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor, sirolimus, proved to be effective in the treatment of refractory or severe cases (Blatt et al. 2010; Boccara et al. 2017; Hammill et al. 2011; Kai et al. 2014; Tasani et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2015a, b; Zhang et al. 2018). A Phase II study demonstrated the response rate of sirolimus therapy in ten patients with KHE and KMP was impressive (Adams et al. 2016). However, many patients needed concurrent medical therapies. As seen in our current study, all patients with KMP requiring multimodal therapy, corticosteroids or sirolimus alone are usually not sufficient to treat KMP. Additionally, data from our multicenter study emphasize that the KHE treatment regimen should be tailored to individual patients and guided by specific clinical circumstances. In cases of KMP, sirolimus in combination with the short-term administration of corticosteroid is recommended for controlling life-threatening conditions (Ji et al. 2017).

Other than KMP, we demonstrated that decreased ROM was another common complication in patients with deep KHE. Patients with deep KHE in the bone–joint–muscle area may suffer from reduced quality of life due to function impairment (e.g., decreased ROM) and chronic pain. The destructive growth patterns of the tumor and the development of muscular and periarticular fibrosis can cause pain and functional limitations, all of which may affect the ability to perform routine daily activities (Schaefer et al. 2017). Remarkably, histological examination of residual lesions, including the three late biopsies presented here, demonstrated features consistent with KHE, as well as a notable dense fibrosis (Enjolras et al. 2000). In this respect, long-term surveillance in patients with KHE is recommended.

Conclusions

KHE without cutaneous involvement may be associated with mortality or severe and lasting morbidity. Incidence of death is higher in lesions with KMP involving retroperitoneum or mediastinum. Diagnosis of KHE without cutaneous involvement is often delayed and preceded by KMP and other complications. Increased awareness of deep KHE may allow for better risk stratification and individualized treatment of KHE. Further investigation into the pathophysiology and development of treatment and surveillance guidelines of KHE are urgently needed to improve outcomes for these patients.

References

Adams DM, Trenor CR, Hammill AM, Vinks AA, Patel MN, Chaudry G, Wentzel MS, Mobberley-Schuman PS, Campbell LM, Brookbank C, Gupta A, Chute C, Eile J, McKenna J, Merrow AC, Fei L, Hornung L, Seid M, Dasgupta AR, Dickie BH, Elluru RG, Lucky AW, Weiss B, Azizkhan RG (2016) Efficacy and safety of sirolimus in the treatment of complicated vascular anomalies. Pediatrics 137(2):e20153257. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3257

Blatt J, Stavas J, Moats-Staats B, Woosley J, Morrell DS (2010) Treatment of childhood kaposiform hemangioendothelioma with sirolimus. Pediatr Blood Cancer 55(7):1396–1398. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.22766

Boccara O, Puzenat E, Proust S, Leblanc T, Lasne D, Hadj-Rabia S, Bodemer C (2017) The effects of sirolimus on Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon coagulopathy. Br J Dermatol. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15883

Croteau SE, Liang MG, Kozakewich HP, Alomari AI, Fishman SJ, Mulliken JB, Trenor CR (2013) Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: atypical features and risks of Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon in 107 referrals. J Pediatr 162(1):142–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.06.044

Croteau SE, Kozakewich HP, Perez-Atayde AR, Fishman SJ, Alomari AI, Chaudry G, Mulliken JB, Trenor CR (2014) Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis: a distinct aggressive lymphatic anomaly. J Pediatr 164(2):383–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.10.013

Drolet BA, Trenor CR, Brandao LR, Chiu YE, Chun RH, Dasgupta R, Garzon MC, Hammill AM, Johnson CM, Tlougan B, Blei F, David M, Elluru R, Frieden IJ, Friedlander SF, Iacobas I, Jensen JN, King DM, Lee MT, Nelson S, Patel M, Pope E, Powell J, Seefeldt M, Siegel DH, Kelly M, Adams DM (2013) Consensus-derived practice standards plan for complicated Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma. J Pediatr 163(1):285–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.080

Enjolras O, Wassef M, Mazoyer E, Frieden IJ, Rieu PN, Drouet L, Taieb A, Stalder JF, Escande JP (1997) Infants with Kasabach–Merritt syndrome do not have “true” hemangiomas. J Pediatr 130(4):631–640

Enjolras O, Mulliken JB, Wassef M, Frieden IJ, Rieu PN, Burrows PE, Salhi A, Leaute-Labreze C, Kozakewich HP (2000) Residual lesions after Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon in 41 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 42(2 Pt 1):225–235

Fernandes VM, Fargo JH, Saini S, Guerrera MF, Marcus L, Luchtman-Jones L, Adams D, Meier ER (2015) Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis: unifying features of a heterogeneous disorder. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62(5):901–904. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.25278

Fernandez-Pineda I, Lopez-Gutierrez JC, Ramirez G, Marquez C (2010) Vincristine-ticlopidine-aspirin: an effective therapy in children with Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon associated with vascular tumors. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 27(8):641–645. https://doi.org/10.3109/08880018.2010.508299

Fernandez-Pineda I, Lopez-Gutierrez JC, Chocarro G, Bernabeu-Wittel J, Ramirez-Villar GL (2013) Long-term outcome of vincristine-aspirin-ticlopidine (VAT) therapy for vascular tumors associated with Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60(9):1478–1481. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24543

Hall GW (2001) Kasabach–Merritt syndrome: pathogenesis and management. Br J Haematol 112(4):851–862

Hammill AM, Wentzel M, Gupta A, Nelson S, Lucky A, Elluru R, Dasgupta R, Azizkhan RG, Adams DM (2011) Sirolimus for the treatment of complicated vascular anomalies in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer 57(6):1018–1024. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.23124

Hu PA, Zhou ZR (2018) Clinical and imaging features of Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma. Br J Radiol 91(1086):20170798. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20170798

Iwami D, Shimaoka S, Mochizuki I, Sakuma T (2006) Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma of the mediastinum in a 7-month-old boy: a case report. J Pediatr Surg 41(8):1486–1488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.04.013

Ji Y, Chen S, Xiang B, Li K, Xu Z, Yao W, Lu G, Liu X, Xia C, Wang Q, Li Y, Wang C, Yang K, Yang G, Tang X, Xu T, Wu H (2017) Sirolimus for the treatment of progressive kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: a multicenter retrospective study. Int J Cancer 141(4):848–855. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.30775

Ji Y, Yang K, Peng S, Chen S, Xiang B, Xu Z, Li Y (2018) Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: clinical features, complications and risk factors for Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon. Br J Dermatol 179(2):457–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.16400

Kai L, Wang Z, Yao W, Dong K, Xiao X (2014) Sirolimus, a promising treatment for refractory Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 140(3):471–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-013-1549-3

Kasabach H, Merritt K (1940) Capillary hemangioma with extensive purpurareport of a case. Am J Dis Child 5(59):1070–1093. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1940.01990160135009

Lisle JW, Bradeen HA, Kalof AN (2009) Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma in multiple spinal levels without skin changes. Clin Orthop Relat Res 467(9):2464–2471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-009-0838-2

Liu XH, Li JY, Qu XH, Yan WL, Zhang L, Yang C, Zheng JW (2016) Treatment of kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma. Int J Cancer 139(7):1658–1666. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.30216

Lyons LL, North PE, Mac-Moune LF, Stoler MH, Folpe AL, Weiss SW (2004) Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: a study of 33 cases emphasizing its pathologic, immunophenotypic, and biologic uniqueness from juvenile hemangioma. Am J Surg Pathol 28(5):559–568

Mahajan P, Margolin J, Iacobas I (2017) Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon: classic presentation and management options. Clin Med Insights Blood Disord 10:1179545X–17699849X. https://doi.org/10.1177/1179545X17699849

O’Rafferty C, O’Regan GM, Irvine AD, Smith OP (2015) Recent advances in the pathobiology and management of Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon. Br J Haematol 171(1):38–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.13557

Rodriguez V, Lee A, Witman PM, Anderson PA (2009) Kasabach–merritt phenomenon: case series and retrospective review of the mayo clinic experience. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 31(7):522–526. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181a71830

Ryan C, Price V, John P, Mahant S, Baruchel S, Brandao L, Blanchette V, Pope E, Weinstein M (2010) Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon: a single centre experience. Eur J Haematol 84(2):97–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01370.x

Ryu YJ, Choi YH, Cheon JE, Kim WS, Kim IO, Park JE, Kim YJ (2017) Imaging findings of Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma in children. Eur J Radiol 86:198–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.11.015

San MF, Spurbeck W, Budding C, Horton J (2008) Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: a rare cause of spontaneous hemothorax in infancy. Review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg 43(1):e37–e41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.08.068

Sarkar M, Mulliken JB, Kozakewich HP, Robertson RL, Burrows PE (1997) Thrombocytopenic coagulopathy (Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon) is associated with Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and not with common infantile hemangioma. Plast Reconstr Surg 100(6):1377–1386

Schaefer BA, Wang D, Merrow AC, Dickie BH, Adams DM (2017) Long-term outcome for kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: a report of two cases. Pediatr Blood Cancer 64(2):284–286. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26224

Tasani M, Ancliff P, Glover M (2017) Sirolimus therapy for children with problematic kaposiform haemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma. Br J Dermatol. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15640

Tlougan BE, Lee MT, Drolet BA, Frieden IJ, Adams DM, Garzon MC (2013) Medical management of tumors associated with Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon: an expert survey. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 35(8):618–622. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0b013e318298ae9e

Wang Z, Li K, Dong K, Xiao X, Zheng S (2015a) Successful treatment of Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon arising from Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma by sirolimus. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 37(1):72–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0000000000000068

Wang Z, Li K, Yao W, Dong K, Xiao X, Zheng S (2015b) Steroid-resistant kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: a retrospective study of 37 patients treated with vincristine and long-term follow-up. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62(4):577–580. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.25296

Wang C, Li Y, Xiang B, Li F, Chen S, Li L, Ji Y (2017) Successful management of pancreatic Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma with sirolimus: case report and literature review. Pancreas 46(5):e39–e41. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPA.0000000000000801

Zhang G, Chen H, Gao Y, Liu Y, Wang J, Liu XY (2018) Sirolimus for treatment of Kaposiform haemangioendothelioma with Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Dermatol. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.16400

Funding

This work was supported by Grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant nos: 81401606 and 81400862) and the Science Foundation for Excellent Youth Scholars of Sichuan University (Grant no: 2015SU04A15).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Author Yi Ji declares that they have no conflict of interest. Author Siyuan Chen declares that they have no conflict of interest. Author Lizhi Li declare that they have no conflict of interest. Author Kaiying Yang declares that they have no conflict of interest. Author Chunchao Xia declares that they have no conflict of interest. Author Li Li declares that they have no conflict of interest. Author Gang Yang declares that they have no conflict of interest. Author Feiteng Kong declares that they have no conflict of interest. Author Guoyan Lu declares that they have no conflict of interest. Author Xingtao Liu declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Written informed consent for publication of this study was obtained from all patients and patient’s parents.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ji, Y., Chen, S., Li, L. et al. Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma without cutaneous involvement. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 144, 2475–2484 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-018-2759-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-018-2759-5