Abstract

Purpose

Long-term administration of adjuvant temozolomide is common practice in many institutions, especially when treatment is well tolerated and stable disease is achieved. In this study, we evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of long-term temozolomide in patients with glioblastoma multiforme treated at a single institution.

Methods

One hundred and fourteen patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma were followed for the course of their disease. Treatment consisted of surgery [gross total resection (GTR) subtotal resection (STR) or biopsy] followed by radiotherapy and concomitant temozolomide. Adjuvant temozolomide was administered until evidence for progressive disease or serious side effects occurred. Follow-up was routinely performed every 3 months.

Results

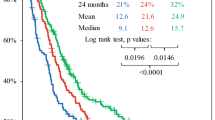

One hundred and fourteen patients with glioblastoma multiforme received a median of 6 cycles of adjuvant first-line temozolomide (range 1–57). For patients with less than 6 cycles, chemotherapy was stopped in 60% for reasons other than progression, while only in 17% of patients receiving 6 or more (P < 0.0001). Median TTP was 7 months (95% CI: 6–10 months). PFS after 6 months was 53%. Median OS in all patients was 15 months (95% CI: 13–18 months). TTP and OS directly correlate with the amount of chemotherapy cycles (each P < 0.0001). No significant influence of the extent of surgical treatment on PFS (P = 0.2141) and OS (P = 0.4308) could be detected.

Conclusion

This data set suggests that long-term administration of temozolomide is safe and efficacious. Side effects occur more frequently in the early phase of drug administration (<6 cycles). There is a strong correlation of long-term temozolomide on PFS and OS regardless of the extent of surgery and other factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Purpose

Glioblastoma multiforme is the most common and highly malignant brain tumour (DeAngelis 2001). The prognosis is dismal, despite concomitant radiochemotherapy followed by adjuvant 6 cycles of temozolomide having become the standard treatment with an overall survival of 14.6 months (Stupp et al. 2005). For neurooncologists and patients, it is sometimes difficult to justify stopping an effective and well-tolerated treatment after 6 cycles when stable disease is achieved. Therefore, it is common practice to prolong the administration of adjuvant temozolomide cycles until there is evidence for tumour progression (Hau et al. 2007, personal communication). There are recent reports in the literature that patients with malignant gliomas tolerate long-term administration of temozolomide very well (Hau et al. 2007; Khasraw et al. 2009). In this retrospective study, we evaluate the safety and effectiveness of long-term administration of adjuvant temozolomide in 114 patients with primary glioblastoma treated at a single institution.

Patients and methods

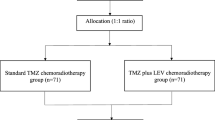

Treatment and follow-up

All patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme treated in our hospital between 2005 and 2008 were retrospectively evaluated. Patients with secondary glioblastoma, recurrent primary glioblastoma or patients receiving postoperative treatment in another institution were not included in this study. Treatment consisted of gross total resection (resection of ≥90% of the initial tumour volume), partial resection or biopsy followed by percutaneous radiotherapy (3D conformal or intensity modulated radiotherapy was given with daily single doses of 2 Gy up to a total dose of 60 Gy) and concomitant temozolomide (patients received a daily dose of 75 mg/m2 for 7 days a week during the duration of radiotherapy). Adjuvant temozolomide with 150–200 mg/m2 for 5 days every 28 days was administered as long as the therapy was tolerated and stable disease was achieved. Patients were followed by MRI and clinical visits every 3 months. Blood testing for haematologic toxicity was performed every 2 weeks. Adverse events were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 3 (Trotti et al. 2003). Upon tumour progression according to the MacDonald criteria or severe side effects related to temozolomide, the therapy regimen was changed (re-operation when possible, re-irradiation when possible, second-line chemotherapy with imatinib, low-dose temozolomide plus COX-II-inhibition or bevacizumab plus irinotecan or a combination of these modalities).

In total, 114 patients (74 men and 40 women, median age 62 years with a range from 22 to 85 years) were included in the retrospective analysis (see Table 1).

Statistical analyses

Time to progression and overall survival were calculated from the time point of diagnosis until progressive disease or death, according to the Kaplan–Meier method. For quantitative data, a 2-sample t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test were performed as appropriate. Binomial proportions were analysed by a Chi square-test. The influence of several parameters (amount of adjuvant chemotherapy cycles, patient’s age, surgical treatment) on overall survival and time to progression was tested with the Logrank test. Furthermore, the Cox proportional hazards model has been used as a multiple model in order to analyse the influence of amount of adjuvant chemotherapy cycles and patients’ age simultaneously. Statistical results with P < 0.05 have been considered statistically significant. All statistical calculations were made with the SAS System, release 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Surgical treatment and tumour histology

Gross total tumour resection was performed in 51 patients, subtotal resection in 47 patients and biopsy was performed in 16 patients. Glioblastoma multiforme was histologically proven in all patients.

Temozolomide administration

The patients received a median of 6 cycles of adjuvant first-line temozolomide with a range from 1 to 57 cycles. About 59 patients received more than 6 cycles of temozolomide, 55 patients at least 6 cycles.

Treatment-related side effects

In 43 patients (38%), chemotherapy was stopped for reasons other than progression, in 39 patients (34%) treatment was stopped due to haematologic side effects (CTC grade 3 thrombocytopenia occurred in 5%, CTC grade 3 pancytopenia in 5% of the patients although no grade 4 haematologic toxicity was detected). Treatment was stopped due to other reasons in 4 patients (e.g. patient’s wish) without any evidence for treatment-related side effects. In all of our patients, there was no evidence for gastrointestinal toxicity or infections during the administration of temozolomide. The rate of severe side effects in our series is low, similar to recent reports (Hau et al. 2007; Khasraw et al. 2009). For patients with less than 6 cycles, chemotherapy was stopped in 60% due to side effects whereas only in 17% of patients receiving 6 or more cycles (P < 0.0001). With an increasing number of chemotherapy cycles, administration had to be stopped less frequently due to side effects (HR 0,909).

Overall survival and time to progression

Median time to progression was 7 months (95% CI: 6–10 months). Progression-free survival after 6 months was 53%. Median overall survival in all observed patients was 15 months (95% CI: 13–18 months). About 20 patients (17.5%) were still alive at the time of evaluation of the study population; their times have been censored. These patients had a median observation time of 28.5 months with a range from 14 to 63 months.

Factors influencing survival periods

Time to progression and overall survival are directly correlated by the amount of chemotherapy cycles (each P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1). No statistically significant influence of the extent of surgical treatment on progression-free survival (P = 0.2141) and overall survival (P = 0.4308) (Fig. 2) could be detected. Patients receiving less than 6 cycles of chemotherapy were significantly older than patients receiving 6 or more cycles (P = 0.0033). Cox regression revealed that number of cycles (P < 0.0001) as well as patients’ age (P = 0.0005) have a significant influence on overall survival. Hazard ratios are 0.915 or 1.030, respectively. For time to progression, however, only the number of cycles had a significant influence (P < 0.0001, HR = 0.911) whereas patients’ age was not significant in this context (P = 0.2541).

Discussion

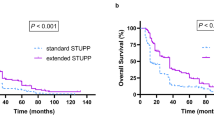

The introduction of combined radio-chemotherapy followed by 6 cycles of high dose temozolomide in patients with glioblastoma multiforme increased overall survival and time to progression for the first time in 30 years in the randomized EORTC trial EORTC-26981/CAN-NCIC-CE3, leading to a progression-free survival after 6 months of 53%, a median survival of 14.6 months and a 2-year survival rate of 26.5% (Stupp et al. 2005).

But the best length of treatment in patients with glioblastoma is up to now not clearly defined; therefore, termination of chemotherapy after 6 adjuvant cycles of temozolomide seems to be arbitrary. It is common practice for many neurooncologists to prolong adjuvant temozolomide in patients with stable disease that tolerate the treatment well (Hau et al. 2007, personal communication). There are, however, concerns about cumulative toxicity when temozolomide is administered for a longer period of time.

In our series, we describe retrospectively a single institution experience of long-term administration of temozolomide as first-line therapy in 114 well-documented patients with primary glioblastoma. We found a low rate of severe side effects in accordance to the EORTC/NCIC study especially in patients receiving more than 6 cycles of temozolomide. This is similar to a recent report focusing on long-term adjuvant temozolomide in primary or recurrent malignant gliomas by Hau et al. 2007. Also in this study no evidence for an increase in side effects was found. Recently, additional data on patients treated with temozolomide for several years were published (Khasraw et al. 2009).

The strongest predictive factor for survival in our patients was the amount of administered chemotherapy cycles. We found a median survival and 2-year survival of 15 months and 27.5% which is similar to the EORTC/NCIC study by Stupp et al. but results are inferior to those published by Hau et al. They reported a median survival time of 30.6 months. This discrepancy might be due to the fact that 17.5% (n = 20) of the patients in our series were still alive at the time of evaluation of the study population and were therefore censored from the Kaplan–Meier analyses. Without censoring, the median survival of 28.5 months of these patients is in line with the data reported by Hau et al. The fact that their data is mainly based on a questionnaire sent to 50 german neurooncological centres reporting about their patient’s clinical course is the main limitation of their study. Furthermore, the patients with anaplastic gliomas (n = 43), primary or recurrent glioblastomas (n = 73) receiving temozolomide as first- or second-line therapy were mixed.

Patients receiving less than 6 cycles of temozolomide in our study were significantly older than patients receiving at least 6 cycles. The results of the Cox regression suggest that time to progress is mainly determined by the number of cycles, not by patients’ age. Also regarding overall survival, the number of cycles seems to play a more important role than patients’ age. Interestingly, the extent of surgical treatment in our patient population had no influence on time to progression or overall survival. Although 44,7% of the patients had complete tumour resection, documented with MRI within the first 48 h after surgery, this was no statistically significant predictor of survival. We therefore conclude that there might be subsets of patients that benefit from prolongation of adjuvant temozolomide cycles, especially younger patients or patients in whom gross total resection is not possible.

Further investigations are needed to define these patients who remain sensitive to temozolomide clearly.

Conclusion

Patients with glioblastoma receiving temozolomide, having stable disease and no significant side effects can continue to receive chemotherapy beyond the standard of 6 cycles arbitrarily defined by the EORTC/NCIC trial. The long-term administration of temozolomide is safe and effective, there seems to be no cumulative toxicity. Related side effects leading to withdrawal of treatment most frequently occur within the first 6 cycles of therapy.

The most important factor influencing time to progression and overall survival appears to be the number of chemotherapy cycles. In this series, no influence of the extent of surgical treatment was observed.

References

DeAngelis LM (2001) Brain Tumours. N Engl J Med 344:114–123

Hau P, Koch D, Hundsberger T et al (2007) Safety and feasibility of long-term temozolomide treatment in patients with high-grade glioma. Neurology 68:688–690

Khasraw M, Bell D, Wheeler H (2009) Long-term use of temozolomide: could you use temozolomide safely for life in gliomas? J Clin Neurosci 16:854–855

Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ et al (2005) Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 35:978–996

Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A et al (2003) CTCAE v3.0: development of a comprehensive grading system for the adverse effects of cancer treatment. Semin Radiat Oncol 13:176–181

Conflict of interest statement

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

M. Seiz and U. Krafft contributed equally to this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seiz, M., Krafft, U., Freyschlag, C.F. et al. Long-term adjuvant administration of temozolomide in patients with glioblastoma multiforme: experience of a single institution. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 136, 1691–1695 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-010-0827-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-010-0827-6