Abstract

Purpose

With the increasing number of elderly patients suffering from cancer, comorbidity and functional impairment become common problems in patients with cancer. Both comorbidity and functional impairment are associated with a shorter survival time in cancer patients, but their independent role has rarely been addressed before.

Methods

Within a prospective trial we recruited 427 cancer patients, irrespective of age and type of cancer, admitted as inpatients prior to the start of chemotherapy. Comorbidity was assessed with the cumulative illness rating scale (CIRS-G), functional impairment with WHO performance status (WHO-PS), basal (ADL) and instrumental (IADL) activities of daily living.

Results

Median follow-up was 34.2 months. A total, 61.4%. of patients died. Median survival time was 21.0 months. Age, kind of tumour (solid vs. haematological), treatment approach (non-curative vs. curative), WHO-PS (2–4 vs. 0–1), IADL (<8 vs. 8), and severe comorbidity (CIRS-level 3–4 vs. none) were significantly associated with shorter survival time in univariate analysis. In a multivariate Cox-regression-analysis, age (HR 1.019; 95%-CI 1.007–1.032; P = 0.003), kind of tumour (HR 1.832; 95%-CI 1.314–2.554; P < 0.001), WHO-PS (HR 1.455; 95%-CI 1.059–2.000; P = 0.021), and comorbidity level 3–4 (HR 1.424; 95%-CI 1.012–2.003; P = 0.043) maintained their significant association.

Conclusions

Age, severe comorbidity, functional impairment, and kind of tumour are independently related to shorter survival time in cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer is the second most leading cause of death in Europe and Northern America (Jemal et al. 2006). About 60% of all people diagnosed with cancer are aged 65 years and more. Due to demographic changes, the number of people with cancer will increase substantially within the next decades (Edwards et al. 2002). Comorbidity and functional impairment are common problems in elderly people.

In cancer patients, a variety of clinical trials and register analyses demonstrated that advanced age is associated with inadequate diagnosis and treatment and with shorter survival time (Gross et al. 2006; Turner et al. 1999; Yancik et al. 2001). But most trials reporting this fact adjust insufficiently for other factors typically related to advanced age, such as presence of comorbidity and functional impairment.

Comorbidity is the presence of one or more additional disorders in the presence of an index disease (Charlson et al. 1987). But as already described by Feinstein over 30 years ago, despite the fact that comorbidity is of major importance in clinical practice, is has not gained much importance in clinical research (Feinstein 1970; Boyd et al. 2005). The presence of comorbidity is associated with shorter survival time in cancer patients (Read et al. 2004; Nagel et al 2004; Satariano and Ragland 1994; Boulos et al. 2006).

Functional status (FS) or performance status (PS) describes the overall fitness of patients. The term PS is more established in oncology and the term FS in geriatric medicine. David Karnofsky first described the overall fitness of cancer patients by a systematic scoring system (Karnofsky et al. 1948). Different scales to measure performance status (PS) have been established in the past (Buccheri et al. 1996). PS is of prognostic importance for toxicity, early death, and overall survival rate in a variety of tumours (Buccheri et al. 1996). Other scales to measure FS have been established in geriatric medicine, such as activities of daily living (ADL) (Mahoney and Barthel 1965a, b), and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) (Lawton and Brody 1969).

The use of scales established in geriatric medicine on elderly cancer patients provides additional information to castern cooperative oncology group (ECOG) PS (Repetto et al. 2002). The prognostic relevance of ADL or IADL score for survival of cancer patients has only been addressed by two reports so far, one for patients with non-small-cell-lung-cancer (NSCLC) (Maione et al. 2005), and one for patients with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) (Wedding et al. 2006).

Both the frequencies of comorbidity and of poor PS/FS increase with advance in age (Repetto et al. 1998; Extermann et al. 998; Hurria et al 2005). But comorbidity and FS are not two sides of one medal. In geriatric medicine, functional impairment, comorbidity, and frailty are addressed as different aspects with some overlap (Fried et al. 2004). All are increasingly common with advanced age. As Extermann et al. (1998) could demonstrate for elderly cancer patients, comorbidity and functional status are independent in elderly cancer patients.

The independent role of comorbidity and FS or PS on survival in cancer patients has rarely been addressed before (Firat et al. 2002a, b; Truong et al. 2005).

Against this background, we analysed the data collected in a prospective study assessing functional status—with both oncological and geriatric scales—and comorbidity in a non-selected group of cancer patients, independent of sex, age, kind of tumour, treatment approach and stage.

Methods

The study was conducted at the Department of Haematology and Oncology at the University Hospital Jena, Germany. The ethical committee of the Friedrich Schiller University of Jena approved the study.

Patients

Patients aged 18 years and older, admitted as inpatients to the hospital in order to newly undergo first line chemotherapy treatment for current cancer stage were asked to participate in a clinical trial including measurement of functional status and comorbidity. Informed consent was obtained after patients had received their diagnosis and a recommendation to undergo chemotherapy.

For all patients, data on sex, age, kind of tumour—classified as solid or haematological-diagnosis, and treatment approach, curative versus non-curative, were documented in the patients’ records.

Functional status

Performance-status (PS)

Patients’ PS was measured according to the WHO-PS (World-Health-Organisation 1979). For further analysis, patients were grouped into those with good PS (WHO-PS 0–1) and those with poor PS (WHO-PS 2–4).

Activities of daily living (ADL)

ADL-score was assessed with the Barthel-Index (Mahoney and Barthel 1965a, b). A sum score of all ten items was calculated, and patients were classified as those “without limitations” in case of full sum score (= 100) and those “with limitations” in case of sum score below 100.

Instrumental activities of daily living (IADL)

IADL-score was assessed with the score published by Lawton and Brody (1969). A sum score of all eight items was calculated, and patients were classified‚ as those “without limitations” in case of full sum score (= 8) and those “with limitations” in case of sum score <8. If at least one single item was assessed “with help” (score = 0), the dichotomous appraisal of this patient was “with limitations”.

Comorbidity

Comorbidity at the time of inclusion in the study prior to the start of chemotherapy was recorded with the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale, geriatric version (Linn et al. 1968). It differentiates between 14 organ systems. Every comorbidity of a patient was assigned to one of the 14 organ systems and rated from 0 (no comorbidity) to 4 (extremely severe comorbidity). In the case of an occurrence of more than one disease in one organ system, only the most severe one was rated. If a disease could directly be traced back to the cancer diagnosis, it was not recorded as co-morbidity. The number of organ systems with severe comorbidity (level 3 or 4) was used for further analyses.

Statistics

Data management and data analysis were performed with the statistical packages SPSS® Version 12 and SAS® Release 8.02. To assure high quality of data concerning completeness, rightness and consistency, plausibility checks were performed. The statistical measurements frequency and relative frequency were calculated for categorical variables, mean and standard deviation for metrical variables. The outcome of a statistic test with P < 0.05 is called significant, and with P < 0.10 a trend. Survival analysis was performed according to Kaplan–Meier analysis. Log rank test to compare differences in survival between groups, and Cox-regression analysis for those items with significant results in univariate analysis were calculated. For selection of variables (addition of a further variable to the Cox model) difference of −2 Log Likelihood was tested for statistical significance (P value < 0.05).

Results

Patients’ characteristics

Four hundred and twenty-seven patients were included. Patients’ characteristics are reported in Table 1. Patients’ diagnoses are reported in Fig. 1.

Solid tumours were more common in elderly patients, 41.8% in those aged below 60 years, 54.9% in those aged 60–69 years, 40.2% in those aged 70–79 years, and 19.0% in those aged 80 years and more (P = 0.006).

Treatment approach was curative in 56.4% of patients with haematological neoplasia and 7.9% in those with a solid tumour (P < 0.001), in 48.9% of those aged below 60 years, in 24.1% of those aged 60–69 years, in 26.4% of those aged 70–79 years, and in 14.3% of those aged 80 years and more (P < 0.001). According to classification of the UICC, 78.7% of patients with solid tumour had stage IV disease.

Median time of follow-up of surviving patients was 34.2 months (mean 36.8; 95% CI: 33.9–39.6 months). Two hundred and sixty-two patients died (61.4%). Median survival time of patients who died was 9.1 months (mean 13.2; 95% CI 11.6–14.8 months).

The association between sex, age-group, kind of tumour, treatment approach, WHO-PS, ADL, IADL, and CIRS concerning the relative frequency of patients who died, the median survival time, and the 95% confidence intervals are reported in Table 1.

In a univariate analysis (Kaplan–Meier analysis, Log-rank test), age, kind of tumour, treatment approach, WHO-PS, IADL, and comorbidity were significantly associated with overall survival. For ADL, a trend was observed (see Table 1).

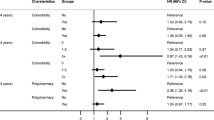

Within a multivariate Cox-regression analysis, age, kind of tumour, WHO-PS, IADL and comorbidity maintained their significant association with overall survival. Treatment approach was not any longer significant, so were IADL. Results of Cox-regression analysis are reported in Table 2.

Model

Due to significant results in the Log rank test, age, kind of tumour, treatment approach, WHO-PS, IADL, and comorbidity were included in a multivariate Cox-regression model to predict survival time. The single most predictive item was treatment approach, followed by kind of tumour, WHO-PS, age, IADL, and comorbidity. The Cox model improved significantly (P < 0.001) when two items were selected. The two items with the best prediction were age and kind of tumour. When three items were included, the model further improved significantly (P = 0.003). As third item, WHO-PS was added. When four items were included, the goodness-of-fit further improved significantly (P = 0.038). The fourth item with the best improvement of the model was comorbidity. The addition of treatment approach and IADL did not improve the model further. Results of the model are reported in Table 3.

Discussion

Survival is one of the major end-points within the care for cancer patients. Factors influencing survival time can be related to the disease, to the patient, and to the treatment. Whereas the influence of characteristics of the disease has been studied extensively, patients’ characteristics, especially in elderly cancer patients’ are less well described in most trials. Geriatric medicine has established geriatric assessment, amongst others to improve the description of patients’ characteristics (Rubenstein et al. 1989).

Most of the trials reporting survival dependence of age adjust insufficiently for age-related changes such as comorbidity and functional impairment. The presented report is one of the first addressing age, functional impairment, and comorbidity at the same time, when analysing survival of cancer patients.

Limitations of the presented work are that the analysis includes a heterogeneous cohort of patients and was not restricted to single diagnoses, stages of disease, and to homogeneous treatment protocols. Having in mind that for different diagnoses a variety of prognostic important variables are known, the sample size is rather small. Thus the presented data shall stimulate further trials in homogeneous cohorts of patients including a structured assessment of comorbidity and of functional status.

In the past, this has been performed for patients with NSCLC. Firat et al. (2002a, b) demonstrated that comorbidity and poor PS were independent prognostic factors for overall survival in stage I and stage III NSCLC. Age did not contribute significantly. According to Maione et al. (2005), in elderly patients with advanced NSCLC limitations in IADL are one of the important prognostic factors for poor survival in addition to ECOG-PS = 2, higher number of metastatic sites, and poor initial quality of life, but not comorbidity.

In a cohort of patients with AML, we could demonstrate that limitations in IADL are of prognostic importance even after adjusting for other major prognostic factors, such as poor PS and adverse cytogenetic risk group (Wedding et al. 2006). However, comorbidity did not have a significant influence.

In a population-based analysis of patients with endometrial carcinoma, Truong et al. (2005) could not identify comorbidity as a factor of survival in a multivariate Cox model, including age at diagnosis, PS, stage, grade, lymphovascular invasion, surgery, and radiotherapy use.

For further entities, analyses like these are important, to learn whether age remains to be an adverse prognostic factor even after adjusting for age-associated changes, such as functional impairment and comorbidity.

Read et al. (2004) reported on the influence of comorbidity on one year’s survival rate in 11,558 patients with breast, lung, colon, or prostate cancer. When the survival by the kind of tumour and the stage was very short, comorbidities had no significant influence on 1-year survival rate, but they did not include PS in their analysis. As the median time of survival was 21.0 months in our cohort of patients, the results are in line with the data reported by Read.

A further limitation is that we included inpatients only. Thus the cohort of patients may describe a group of patients with poor prognoses compared to patients who can be treated as outpatients. In addition, the cohort comprises a high rate (55.5%) of patients with haematological malignancies, compared to 6–10% in all cancer patients in Germany. This reflects the restriction of the trial to inpatients, the specialisation of our hospital and a referral bias. As the survival of patients with haematological type of cancer is longer than that of patients with a solid tumour, both limitations might equalise each other.

Guidelines for the treatment of elderly patients with cancer recommend a systematic geriatric assessment, including amongst others ADL, IADL, and co-morbidities (Friedrich et al. 2003; Extermann et al. 2005). The presented data support the need to collect systematic data on PS/FS and co morbidities in cancer patients, to improve prognostic accuracy, and potentially improve the care for elderly patients with cancer in future.

References

Boulos DL, Groome PA, Brundage MD et al (2006) Predictive validity of five comorbidity indices in prostate carcinoma patients treated with curative intent. Cancer 106(8):1804–1814

Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW (2005) Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. Jama 294(6):716–724

Buccheri G, Ferrigno D, Tamburini M (1996) Karnofsky ECOG performance status scoring in lung cancer: a prospective, longitudinal study of 536 patients from a single institution. Eur J Cancer 32A(7):1135–1141

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40(5):373–383

Edwards BK, Howe HL, Ries LA et al (2002) Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973–1999, featuring implications of age and aging on US cancer burden. Cancer 94(10):2766–2792

Extermann M, Overcash J, Lyman GH, Parr J, Balducci L (1998) Comorbidity and functional status are independent in older cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 16(4):1582–1587

Extermann M, Aapro M, Bernabei R et al (2005) Use of comprehensive geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: recommendations from the task force on CGA of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG). Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 55(3):241–252

Feinstein AR (1970) The pre-therapeutic classification of co-morbidity in chronic disease. J Chronic Dis 23:455–469

Firat S, Bousamra M, Gore E, Byhardt RW (2002a) Comorbidity and KPS are independent prognostic factors in stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 52(4):1047–1057

Firat S, Byhardt RW, Gore E (2002b) Comorbidity and Karnofksy performance score are independent prognostic factors in stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: an institutional analysis of patients treated on four RTOG studies. Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 54(2):357–364

Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G (2004) Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 59(3):255–263

Friedrich C, Kolb G, Wedding U, Pientka L (2003) Comprehensive geriatric assessment in the elderly cancer patient. Onkologie 26(4):355–360

Gross CP, McAvay GJ, Krumholz HM, Paltiel AD, Bhasin D, Tinetti ME (2006) The effect of age and chronic illness on life expectancy after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer: implications for screening. Ann Int Med 145(9):646–653

Hurria A, Gupta S, Zauderer M, et al (2005) Developing a cancer-specific geriatric assessment: a feasibility study. Cancer 104(9):1998–2005

Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E et al (2006) Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin 56(2):106–130

Karnofsky DA, Adelmann WH, Craver FL (1948) The use of nitrogen mustard in the palliative treatment of carcinoma. Cancer 1:634–656

Lawton MP, Brody EM (1969) Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 9(3):179–186

Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L (1968) Cumulative illness rating scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 16(5):622–626

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW (1965a) Functional evaluation. Md Med J 14:61–65

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW (1965b) Functional evaluation: the barthel index. Md State Med J 14:61–65

Maione P, Perrone F, Gallo C et al (2005) Pretreatment quality of life and functional status assessment significantly predict survival of elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer receiving chemotherapy: a prognostic analysis of the multicenter Italian lung cancer in the elderly study. J Clin Oncol 23(28):6865–6872

Nagel G, Wedding U, Rohrig B, Katenkamp D (2004) The impact of comorbidity on the survival of postmenopausal women with breast cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 130(11):664–670

Read WL, Tierney RM, Page NC et al (2004) Differential prognostic impact of comorbidity. J Clin Oncol 22(15):3099–3103

Repetto L, Venturino A, Vercelli M et al (1998) Performance status and comorbidity in elderly cancer patients compared with young patients with neoplasia and elderly patients without neoplastic conditions (see comments). Cancer 82(4):760–765

Repetto L, Fratino L, Audisio RA et al (2002) Comprehensive geriatric assessment adds information to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status in elderly cancer patients: an Italian Group for Geriatric Oncology Study. J Clin Oncol 20(2):494–502

Rubenstein LZ, Siu AL, Wieland D (1989) Comprehensive geriatric assessment: toward understanding its efficacy. Aging (Milano) 1(2):87–98

Satariano WA, Ragland DR (1994) The effect of comorbidity on 3-year survival of women with primary breast cancer. Ann Int Med 120(2):104–110

Truong PT, Kader HA, Lacy B et al (2005) The effects of age and comorbidity on treatment and outcomes in women with endometrial cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 28(2):157–164

Turner NJ, Haward RA, Mulley GP, Selby PJ (1999) Cancer in old age–is it inadequately investigated and treated? BMJ 319(7205):309–312

Wedding U, Rohrig B, Klippstein A, Fricke HJ, Sayer HG, Hoffken K (2006) Impairment in functional status and survival in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 132(10):665–671

World-Health-Organisation (1979) WHO handbook for reporting results of cancer treatment. WHO, Geneva

Yancik R, Wesley MN, Ries LA, Havlik RJ, Edwards BK, Yates JW (2001) Effect of age and comorbidity in postmenopausal breast cancer patients aged 55 years and older. Jama 285(7):885–892

Acknowledgment

The study was supported by German Cancer Aid (Grant No. 70-2445-Hö-3). Ulrich Wedding is currently research follow of the “Forschungskolleg Geriatrie” of the Robert Bosch Foundation, Stuttgart, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wedding, U., Röhrig, B., Klippstein, A. et al. Age, severe comorbidity and functional impairment independently contribute to poor survival in cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 133, 945–950 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-007-0233-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-007-0233-x