Abstract

This narrative review aims to present an overview of the COVID-19 pandemic’s effects on the landscape of pediatric infectious diseases. While COVID-19 generally results in mild symptoms and a favorable prognosis in children, the pandemic brought forth significant consequences. These included persistent symptoms among infected children (“long COVID”), a profound transformation in healthcare utilization (notably through the widespread adoption of telemedicine), and the implementation of optimization strategies within healthcare settings. Furthermore, the pandemic resulted in alterations in the circulation patterns of respiratory pathogens, including influenza, RSV, and Streptococcus pneumoniae. The possible reasons for those changes are discussed in this review. COVID-19 effect was not limited to respiratory infectious diseases, as other diseases, including urinary tract and gastrointestinal infections, have displayed decreased transmission rates, likely attributable to heightened hygiene measures and shifts in care-seeking behaviors. Finally, the disruption of routine childhood vaccination programs has resulted in reduced immunization coverage and an upsurge in vaccine hesitancy. In addition, the pandemic was associated with issues of antibiotic misuse and over-prescription.

Conclusion: In conclusion, the COVID-19 pandemic has left a profound and multifaceted impact on the landscape of pediatric infectious diseases, ranging from the emergence of “long COVID” in children to significant changes in healthcare delivery, altered circulation patterns of various pathogens, and concerning disruptions in vaccination programs and antibiotic usage.

What is Known: • COVID-19 usually presents with mild symptoms in children, although severe and late manifestations are possible. • The pandemic resulted in a dramatically increased use of health care services, as well as alterations in the circulation patterns of respiratory pathogens, decreased rates of other, non-respiratory, infections, disruption of routine childhood vaccination programs, and antibiotic misuse. | |

What is New: • Possible strategies to tackle future outbreaks are presented, including changes in health care services utilization, implementation of updated vaccine programs and antibiotic stewardship protocols. • The decline in RSV and influenza circulation during COVID-19 was probably not primarily related to NPI measures, and rather related to other, non-NPI measures implementation, including specific pathogen-host interactions on the level of the biological niche (the nasopharynx). |

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In May 2023, the World Health Organization declared the end of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, marking a significant milestone in the global fight against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) [1]. The pandemic caused a massive global health crisis, which led to a large-scale change in the practice of pediatric medicine, affecting various social, medical, scientific, and behavioral aspects [2]. Scientists and public health officials around the globe were promoted to enhance our understanding of this devastating illness quickly. As a result, 3 years after the outbreak, we have more insight into the pandemic management and control and have witnessed the emergence of new countermeasures. In this article, we will present an overview of our current knowledge of the pandemic effects on the landscape of pediatric infectious diseases. Significant changes will be highlighted and notable breakthroughs, some surprising and others expected, will be presented, while pointing out knowledge gaps which require further exploration.

Direct impact of COVID-19 on children

Acute COVID-19 in children

Children with COVID-19 usually present with mild symptoms and are at lower risk of hospitalization and life-threatening complications, compared with adults [3]. Numerous surveillance studies on a national level confirmed that disease outcomes in children were mild, with fewer hospitalizations and mortality rates than in adults [4,5,6,7,8]. Even in hospitalized cases, only a third presented with a significant respiratory involvement [4, 9,10,11,12] Furthermore, severe manifestations of COVID-19, including the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), are rare. Although morbidity can be severe, the prognosis of MIS-C and other COVID-19 severe presentations are usually favorable with suitable treatment [13, 14]. The excellent outcomes of young febrile infants with COVID-19 closely resembled other respiratory viral etiologies of fever in this age group, with a low number of fatalities [15].

Long COVID-19

COVID-19 long-term complications were a source of major concern among healthcare providers. There is a variability in reports from different countries regarding the scope of this phenomenon, and the specific symptomology it can present in children affected [16, 17]. An elaborate discussion on this subject will be presented by Töpfer et al.

Burden on healthcare services

Despite the benign course of the disease in the pediatric population, the COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted healthcare service utilization [18,19,20]. The lack of understanding of the COVID-19 pathophysiology and the prognosis in children led to a massive investment in resources during the pandemic. The immense burden of the pandemic on healthcare systems and the long-term sequelae of COVID-19 are significant considerations in attempting to create the most effective response at different levels of treatment [21]. In primary care, the COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated how a global health crisis can profoundly alter healthcare delivery within communities, evident by shifts in patient consultation methods [22]. In the realm of secondary and tertiary healthcare systems, the pandemic has shed light on emerging imperatives such as safeguarding the health of healthcare professionals, creating new protocols and collaborative teamwork, and addressing logistical concerns, including the need for the future design of hospitals to enable effective isolation measures [23]. In addition, it is important to highlight the neglect of children with chronic conditions during the pandemic. These patients might have suffered from a lack of diagnosis, treatment, or additional symptomology during the pandemic period.[24]

All of the above should alert healthcare policymakers regarding the need to tackle future outbreaks with various tools, including (but not limited to) telemedicine, cohorts of patients, healthcare professionals training, and maximizing personnel usage [25, 26]. In addition, due to the long but unknown effect of COVID-19, follow-up on patients might be required and taken into consideration by the physician [25, 27].

COVID-19 impact on other viruses/bacteria

Decline in the rates of respiratory infections

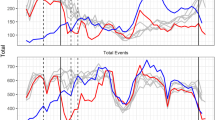

During the pandemic, the patterns of some prevalent pediatric infectious diseases changed dramatically [28]. At the peak of COVID-19, a decrease was noted in other respiratory infectious diseases, such as influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and other vaccine-preventable diseases [29, 30]. Before 2020, the seasonal peaks of RSV and non-pandemic influenza viruses typically occurred during the winter season in the northern and the southern hemispheres, excluding tropical regions [31, 32]. However, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted these patterns [29, 30] resulting in the absence of regular virus circulation in many areas for over a year, which resurged unexpectedly in various ways [28]. Surprisingly, other respiratory viruses, such as rhinovirus and enterovirus (RV/EV), as well as adenovirus, have experienced only minor changes in their circulation and remained near pre-pandemic seasonal levels [33]. The decreased infection rate was not limited to viral infections, as the rates of overall and bacteremic pneumonia, along with other pneumococcal diseases, have also decreased [34]. The cause of this substantial reduction is presently unclear and could be attributed to a variety of factors.

Reasons for changes in other respiratory pathogen circulation

Several researchers have attributed these changes to non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) and mitigation measures used in many countries, such as reduced social interactions (social distancing), increased use of personal protective measures, and changes in healthcare-seeking behaviors [35,36,37,38]. According to these researchers, non-pharmaceutical interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic altered not only the spread of SARS-CoV-2, but also the predictable seasonal circulation patterns of many endemic viral illnesses in children [39].

In contrast, some researchers were reluctant to accept the argument that NPI campaigns affected the circulation patterns of endemic viral infections. As was mentioned above, the circulation patterns of several respiratory viruses, like rhinovirus, enterovirus (RV/EV), and adenovirus, were not affected as RSV and influenza circulation patterns were [33]. Furthermore, the COVID-19 infection rate, the goal of the NPI campaign, was not necessarily affected by social distancing [40]. Only a successful vaccination campaign was effective in reducing morbidity and mortality rates of the disease caused by SARS‑CoV‑2 [41, 42].

Evidently, other explanations are needed for the noted changes in RSV and Influenza circulation patterns [43]. Several studies suggested that the phenomenon of reduced RSV and influenza circulation was a result of the competition of viruses with COVID-19 on the biological niche of the nasopharynx, as it resembles the gate point of respiratory infection [28, 44]. Researchers suggested a variety of theories to explain these dynamics. During the peak of the pandemic, this competition was determined by the benefit of numbers and, therefore, to the wide spread of COVID-19 and the near elimination of other viruses’ circulation. Indeed, as COVID-19 numbers declined, some reports suggested that several respiratory viruses, such as RSV and influenza, returned to their typical, pre-pandemic circulation pattern [45, 46]. This was driven by natural immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and the increased vaccination rates that led to the development of mucosal immunity [47,48,49].

The competition between different respiratory viruses (i.e., the changing circulation patterns) was a result of the COVID-19 effect on the biological niche of the nasopharynx itself. SARS-CoV-2 binds to specific receptors on the surface of epithelial cells of the respiratory tract and therefore affects the pathogen-host interaction of viruses with different viral characteristics [50]. One prominent example of this concept was the finding of the differential impact of the pandemic on enveloped vs. non-enveloped viruses. In the case of enveloped viruses, such as influenza, COVID-19 resulted in the near-complete interruption of transmission of those viruses, as opposed to the impact on non-enveloped viruses, like rhinovirus, which were almost not affected [51].

Non-pharmaceutical interventions probably did not affect the pneumococcal transmission, as studies from Israel and France presented steady pneumococcal carriage and density rates in children during the pandemic [34, 52, 53]. Despite this fact, invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), and other pneumococcal diseases (e.g., pneumonia) rates declined substantially [34]. Therefore, it is more likely to assume that the decline in IPD and pneumonia rates was not affected by NPI’s unmeasured effect on carriage rate, but rather by the disruption of co-infection of viral agents, such as RSV, needed to generate the disease [54].

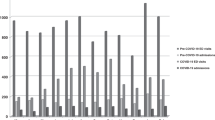

Notably, there were reports of resurgence of RSV and other respiratory pathogens post-COVID-19 pandemic [43, 55]. It was suggested that this recuperation can be a result of genetic bottlenecking brought on by case reduction during the COVID-19 pandemic, now leading to a rise in viral genetic diversity [43, 56]. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Group, in an attempt to elucidate the unanticipated upsurge in respiratory infections occurring between seasons on a global scale, introduced the concept of “immunity debt” [57]. According to this hypothesis, extended periods of limited viral exposure might have led to an increased pool of immunologically susceptible individuals, notably among children. Consequently, the re-emergence of viruses could result in more severe disease outcomes. Supporting this evidence is the resurgence of RSV cases during the winter of 2021–2022 in Italy [58], increased incidence of IPD in England [59], and other reports of hand-foot-mouth epidemic in Egypt [60]. Yet, this phenomenon is not yet fully explained [43, 56].

Future implications

The potentially modified effect of RSV and influenza on IPD suggests that interventions targeting respiratory viruses, such as passive immunization like monoclonal antibodies or active vaccines for RSV and influenza, could prevent a large proportion of pediatric IPD and pneumonia cases in the future [52, 53, 61, 62]. When preparing for the next pandemic, it is crucial to understand the possibility of displacement of viral transmission and seasonality and tackle this by vaccination against RSV and flu according to age and not necessarily according to seasonality.

Reduction in other, non-respiratory, infectious agents

COVID-19 pandemic effects were noted to be wider than just on infectious respiratory disease, as reduced rates of other prevalent diseases in children, such as urinary tract and gastrointestinal infections, were noted, during the pandemic [63]. A study examining data on 375,000 children from Massachusetts pediatric primary care network reported a decline in 12 common childhood infections, including skin and soft tissue infections (− 35%) [64]. In Denmark, acute gastroenteritis in children decreased significantly during COVID-19 restrictions [65]. Similarly, there was a decrease in the incidence of urinary tract infections in Finnish children, with the most prominent decrease observed in daycare-aged children [66]. Probably none of the prevalent infectious mentioned above is presumed to be directly affected by SARS-CoV-2. Still, all those infections presented a notable decline in their incidence. This phenomenon can be explained in several manners [39, 66]. First, improved hygiene measures and social restrictions may have influenced the transmission of pathogens. Second, changes in care-seeking behaviors can play a role as individuals opt out of seeking medical care for such ailments. This argument can also explain why children referring to the emergency department, in case of febrile urinary tract infections, were more severely ill than in the previous two years, probably due to a delayed access, caused by the fear of potential hospital-acquired SARS-CoV-2 infection [67]. In addition, the decline could be a result of a lack of laboratory services and other public health resources invested differently [39, 68].

As for the post-pandemic period, a growing body of knowledge is collected to understand the effect of COVID-19 on the behavior of non-respiratory infectious agents. For example, the severity and number of group A streptococcus cases in Spain and France in children increased significantly in 2022, compared to the pre-pandemic COVID-19 period [69, 70]. Possible explanations might be “immune debt” [57] or genetic changes of the pathogen itself that are not fully understood [71].

Future implications

Understanding the effect of the pandemic on the landscape of non-respiratory agents is crucial for our efforts to protect children from severe illness. Health system resources should be invested fluidly, according to recorded data, in order to detect and treat the current map of infectious diseases. Special campaigns should be considered to encourage parents to seek treatment earlier to reduce severe disease sequelae. In addition, investing in effective tools, like improving hygiene measures, can help reduce the transmission of pathogens and prevent disease.

Research (drugs, vaccines, publications)

COVID-19 has had a profound impact on global pediatric research. The pandemic has witnessed an unprecedented surge in research publications dedicated to this disease, encompassing efforts to find solutions and explore various applied or related aspects [72,73,74]. A significant decline in non-COVID-19 research alongside an exponential rise in COVID-19-related publications was observed [75]. Additionally, a displacement of clinical trial publications (− 24%) and a redirection of research grants away from fields less closely tied to COVID-19 were noted [76]. This rapid influx of COVID-19 publications, driven in part by editorial policy, may have influenced the overall quality of research output, leading to a neglect of COVID-19-unrelated publications. On the other hand, the worldwide scientific adaptation to COVID-19 has led to unprecedented international collaboration that was considered impossible before [76, 77].

Vaccines

The rapid development of vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic has been a major achievement in the history of modern medicine [78]. The development timeline of the COVID-19 vaccine is nothing short of remarkable, with the first SARS-CoV-2 sequences published to phase 1 trials completed in just 6 months. Additionally, in an effort to promote vaccination in particular vulnerable cohorts, such as pregnant and breastfeeding women, children, and immunocompromised patients, these populations were included in vaccine trial very early in the course of the trials, when the benefit-risk profile of these vaccines was still limited [79]. This timeline starkly contrasts the typical vaccine development timeline of 3 to 9 years [80]. Several factors have contributed to the accelerated development of COVID-19 vaccines. Firstly, there was a prior understanding of the spike protein significance in coronavirus pathogenesis and the importance of neutralizing antibodies against it for immunity [81]. Secondly, nucleic acid vaccine technology platforms have evolved, allowing for the rapid creation and manufacture of thousands of doses once the genetic sequence is known. Lastly, development activities can be conducted in parallel without increasing risks to study participants, further accelerating vaccine development. With the demonstrated clinical efficacy of the mRNA-based vaccines, the usage of such technology to prevent and control future epidemics and pandemics looks promising [82]. This technology is also promising in other, non-infectious disease prevention. Indeed, some early studies suggested a potential benefit from mRNA-based vaccines in preventing and treating specific cancers [83,84,85].

Other issues neglected (e.g., decline in vaccine uptake, burden on the health system, society trust in vaccines/anti-vaccine movement)

Impact on routine vaccination programs

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted routine childhood vaccination programs in many countries. Immunization coverage was lower in COVID-19-affected children than in unaffected children, ranging from as low as 2% lower for BCG and hepatitis B, 0 to 9% for diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccines, followed by a 10% reduction for polio [86]. Coverage reduction was more remarkable in vaccine doses given in later age groups as at least a 28% decrease was noted in human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in England in the year 2020 [87]. It is important to recognize that among population subgroups, COVID-19 affected those from rural areas and low middle-income countries (LMIC), who experienced the highest reduction in vaccine coverage [86, 88]. Lockdowns, travel restrictions, and reduced access to healthcare facilities have resulted in missed or delayed vaccinations for many children. For example, the pandemic limitations have directly affected HPV vaccination rates which in some countries is administered at schools [87]. Another reason that cannot be ignored is the anti-vaccine activists around the world, which led to a break of trust and promoted vaccine hesitancy among many parents worldwide [89,90,91]. This has raised concerns about potential outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, such as measles and pertussis, as well as decreased immunity in the pediatric population, which may have long-term consequences on overall public health [92, 93].

Lastly, health systems themselves attributed the decline in vaccination rate, as they decided to redirect resources, to focus on the SARS-CoV-2 vaccination campaign. For instance, Israel officials decided to suspend its yearly influenza vaccination campaign during the pandemic, to improve public complaints about the new SARS-CoV-2 vaccines (personal communication).

Nations must prioritize adequate vaccination to safeguard against potential pandemics caused by vaccine-preventable diseases including mapping populations who suffered from reduced vaccination rates during the pandemic and filling these gaps for the future, while investing in restoring public trust in vaccination campaigns like influenza that were neglected during COVID-19. For example, expanding vaccine programs to a wider range of age groups could help to increase the coverage rates of HPV. It is advised to streamline the vaccination process by reducing waiting times at health centers, addressing parental concerns and anxieties, improving vaccine availability, and expanding access to remote regions. Ensuring comprehensive catch-up programs is crucial, particularly in LMIC, to prevent any gaps in vaccine coverage.

COVID-19 effect on antibiotic use, stewardship programs, and antibiotic resistance

The COVID-19 pandemic intensified the misuse of drugs, including antibiotics, with no evidence of effectiveness in treating SARS-CoV-2 infection [94]. Several studies attributed the misuse of antibiotics to physicians’ fear of co-infection between SARS-CoV-2 and drug-resistant bacteria or fungi in adults [95]. Others explain that pneumonia from SARS-CoV-2 is challenging to distinguish from other viral and bacterial etiologies. Increased prescriptions in adults may also be associated with a higher prevalence of comorbidities and risk of adverse outcomes. Even though antibiotic prescription at COVID-19-related visits was substantially lower for children and adolescents than adults, the phenomenon has increased the prevalence of antibiotics in medical centers and communities [96,97,98]. The gratuitous use of antibiotics for COVID-19 treatment and the lack of a coherent treatment strategy raise concerns about the emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [99]. Broad-spectrum antimicrobials are frequently prescribed to patients hospitalized with COVID-19, which potentially catalyzes the development of AMR. In a systematic review and meta-analysis during the first 18 months of the pandemic, AMR prevalence was high in COVID-19 patients and varied by hospital and geography, although substantial heterogeneity existed [100].

Physicians and public health professionals should prepare for the next outbreak. Health systems should encourage antimicrobial stewardship as a priority while dealing with a viral pandemic. In addition, antibiotic stewardship guidelines should be enforced to avoid antibiotic misuse and contain the emergence of antimicrobial resistance. Vaccine development should focus on desirable pathogens associated with drug resistance that emerge during a viral pandemic. Immunization programs, including maternal vaccination, should be developed to offer circumventing defense in case of a new global health crisis.

Conclusion

In this article, we attempted to present an overview of our current knowledge of the pandemic’s tremendous effects on the landscape of pediatric infectious diseases, in discrepancy to its mild clinical outcomes. We raised our concerns about persistent symptoms among infected children and necessitated substantial adaptations in healthcare utilization, especially the prompting of the implementation of telemedicine and optimization strategies for healthcare personnel.

We presented the alterations in the circulation patterns of respiratory pathogens, including influenza and RSV, and described their relation to the pandemic with possible explanations for the changes recorded, in comparison to other viral and pneumococcal agents. COVID-19 effect was not limited only to respiratory infectious diseases, as other non-respiratory infectious agents, such as urinary tract and gastrointestinal pathogens, have displayed decreased transmission rates, likely attributable to heightened hygiene measures and shifts in care-seeking behaviors.

Notably, the disruption of routine childhood vaccination programs has resulted in reduced immunization coverage and an upsurge in vaccine hesitancy. In addition, when combating antimicrobial resistance, it is important to address the issues of antibiotic misuse and over-prescription. In preparation for future outbreaks, comprehensive vaccination programs must be prioritized, warranting concerted efforts from physicians and public health professionals.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- SARS‑CoV‑2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- MIS-C:

-

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children

- HPV:

-

Human papillomavirus

- LMIC:

-

Low-middle-income countries

- AMR:

-

Antimicrobial resistance

References

Lenharo M (2023) WHO declares end to COVID-19’s emergency phase. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-01559-z

Van Bavel JJ, Baicker K, Boggio PS, Capraro V, Cichocka A, Cikara M, Crockett MJ et al (2020) Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat Hum Behav 4:460–471. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z

Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, Qi X, Jiang F, Jiang Z, Tong S (2020) Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics 145 https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0702

Jarovsky D, de Freitas FG, Zampol RM, de Oliveira TA, Farias CGA, da Silva D, Cavalcante DTG, Nery SB, de Moraes JC, de Oliveira FI, Almeida FJ, Sáfadi MAP (2023) Characteristics and clinical outcomes of COVID-19 in children: a hospital-based surveillance study in Latin America’s hardest-hit city. IJID Reg 7:52–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijregi.2022.12.003

Nikolopoulou GB, Maltezou HC (2022) COVID-19 in children: where do we stand? Arch Med Res 53:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcmed.2021.07.002

Tagarro A, Epalza C, Santos M, Sanz-Santaeufemia FJ, Otheo E, Moraleda C, Calvo C (2020) Screening and severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in children in Madrid. JAMA Pediatr, Spain. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1346

Zachariah P, Johnson CL, Halabi KC, Ahn D, Sen AI, Fischer A, Banker SL, Giordano M, Manice CS, Diamond R, Sewell TB, Schweickert AJ, Babineau JR, Carter RC, Fenster DB, Orange JS, McCann TA, Kernie SG, Saiman L, Columbia Pediatric C-MG (2020) Epidemiology, clinical features, and disease severity in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a children’s hospital in New York City, New York. JAMA Pediatr 174:e202430. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2430

Zimmermann P, Curtis N (2020) Coronavirus infections in children including COVID-19: an overview of the epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment and prevention options in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 39:355–368. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000002660

Castagnoli R, Votto M, Licari A, Brambilla I, Bruno R, Perlini S, Rovida F, Baldanti F, Marseglia GL (2020) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in children and adolescents: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr 174:882–889. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1467

Kim L, Whitaker M, O'Halloran A, Kambhampati A, Chai SJ, Reingold A, Armistead I, et al. (2020) Hospitalization rates and characteristics of children aged <18 years hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 - COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1-July 25, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69:1081–1088. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6932e3

Mehta NS, Mytton OT, Mullins EWS, Fowler TA, Falconer CL, Murphy OB, Langenberg C, Jayatunga WJP, Eddy DH, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS (2020) SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): what do we know about children? A systematic review. Clin Infect Dis 71:2469–2479. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa556

Nachega JB, Sam-Agudu NA, Machekano RN, Rabie H, van der Zalm MM, Redfern A, Dramowski A et al (2022) Assessment of clinical outcomes among children and adolescents hospitalized with COVID-19 in 6 sub-Saharan African countries. JAMA Pediatr 176:e216436. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.6436

Ben-Shimol S, Livni G, Megged O, Greenberg D, Danino D, Youngster I, Shachor-Meyouhas Y et al (2021) COVID-19 in a subset of hospitalized children in Israel. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 10:757–765. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpids/piab035

Chow EJ, Englund JA (2022) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infections in children. Infect Dis Clin North Am 36:435–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idc.2022.01.005

Yarden Bilavski H, Balanson S, Damouni Shalabi R, Dabaja-Younis H, Grisaru-Soen G, Youngster I, Glikman D, Ben Shimol S, Somech E, Tasher D, Stein M, Gottesmanm G, Livni G, Megged O (2021) Benign course and clinical features of COVID-19 in hospitalised febrile infants up to 60 days old. Acta Paediatr 110:2790–2795. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15993

Chua PEY, Shah SU, Gui H, Koh J, Somani J, Pang J (2021) Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of non-severe and severe pediatric and adult COVID-19 patients across different geographical regions in the early phase of pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Investig Med 69:1287–1296. https://doi.org/10.1136/jim-2021-001858

Lopez-Leon S, Wegman-Ostrosky T, Ayuzo Del Valle NC, Perelman C, Sepulveda R, Rebolledo PA, Cuapio A, Villapol S (2022) Long-COVID in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Sci Rep 12:9950. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13495-5

Mafham MM, Spata E, Goldacre R, Gair D, Curnow P, Bray M, Hollings S, Roebuck C, Gale CP, Mamas MA, Deanfield JE, de Belder MA, Luescher TF, Denwood T, Landray MJ, Emberson JR, Collins R, Morris EJA, Casadei B, Baigent C (2020) COVID-19 pandemic and admission rates for and management of acute coronary syndromes in England. Lancet 396:381–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31356-8

Moynihan R, Johansson M, Maybee A, Lang E, Legare F (2020) COVID-19: an opportunity to reduce unnecessary healthcare. BMJ 370:m2752. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2752

Moynihan R, Sanders S, Michaleff ZA, Scott AM, Clark J, To EJ, Jones M, Kitchener E, Fox M, Johansson M, Lang E, Duggan A, Scott I, Albarqouni L (2021) Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on utilisation of healthcare services: a systematic review. BMJ Open 11:e045343. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045343

Mogharab V, Ostovar M, Ruszkowski J, Hussain SZM, Shrestha R, Yaqoob U, Aryanpoor P et al (2022) Global burden of the COVID-19 associated patient-related delay in emergency healthcare: a panel of systematic review and meta-analyses. Global Health 18:58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-022-00836-2

Khalil-Khan A, Khan MA (2023) The impact of COVID-19 on primary care: a scoping review. Cureus 15:e33241. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.33241

Pandita KK, Noor T, Sahoo SK (2022) COVID-19 pandemic: hospital preparedness in a tertiary care hospital in North East India. J Family Med Prim Care 11:2877–2883. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1571_21

Serlachius A, Badawy SM, Thabrew H (2020) Psychosocial challenges and opportunities for youth with chronic health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JMIR Pediatr Parent 3:e23057. https://doi.org/10.2196/23057

Haldane V, De Foo C, Abdalla SM, Jung AS, Tan M, Wu S, Chua A, Verma M, Shrestha P, Singh S, Perez T, Tan SM, Bartos M, Mabuchi S, Bonk M, McNab C, Werner GK, Panjabi R, Nordstrom A, Legido-Quigley H (2021) Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from 28 countries. Nat Med 27:964–980. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01381-y

Mann DM, Chen J, Chunara R, Testa PA, Nov O (2020) COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: evidence from the field. J Am Med Inform Assoc 27:1132–1135. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa072

Arsenault C, Gage A, Kim MK, Kapoor NR, Akweongo P, Amponsah F, Aryal A et al (2022) COVID-19 and resilience of healthcare systems in ten countries. Nat Med 28:1314–1324. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01750-1

Komori A, Mori H, Naito T (2022) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on other infections differs by their route of transmission: a retrospective, observational study in Japan. J Infect Chemother 28:1700–1703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiac.2022.08.022

Toelen J, Ritz N, de Winter JP (2021) Changes in pediatric infections during the COVID-19 pandemic: ‘a quarantrend for coronials’? Eur J Pediatr 180:1965–1967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-021-03986-4

Van Brusselen D, De Troeyer K, Ter Haar E, Vander Auwera A, Poschet K, Van Nuijs S, Bael A, Stobbelaar K, Verhulst S, Van Herendael B, Willems P, Vermeulen M, De Man J, Bossuyt N, Vanden Driessche K (2021) Bronchiolitis in COVID-19 times: a nearly absent disease? Eur J Pediatr 180:1969–1973. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-021-03968-6

Broberg EK, Waris M, Johansen K, Snacken R, Penttinen P, European Influenza Surveillance N (2018) Seasonality and geographical spread of respiratory syncytial virus epidemics in 15 European countries, 2010 to 2016. Euro Surveill 23 https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.5.17-00284

Kenah E, Chao DL, Matrajt L, Halloran ME, Longini IM, Jr. (2011) The global transmission and control of influenza. PLoS One 6:e19515. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019515

Olsen SJ, Winn AK, Budd AP, Prill MM, Steel J, Midgley CM, Kniss K, et al. (2021) Changes in influenza and other respiratory virus activity during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, 2020–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 70:1013–1019. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7029a1

Danino D, Ben-Shimol S, van der Beek BA, Givon-Lavi N, Avni YS, Greenberg D, Weinberger DM, Dagan R (2022) Decline in pneumococcal disease in young children during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in israel associated with suppression of seasonal respiratory viruses, despite persistent pneumococcal carriage: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 75:e1154–e1164. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab1014

Chinazzi M, Davis JT, Ajelli M, Gioannini C, Litvinova M, Merler S, Pastore YPA, Mu K, Rossi L, Sun K, Viboud C, Xiong X, Yu H, Halloran ME, Longini IM Jr, Vespignani A (2020) The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science 368:395–400. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba9757

Heymann DL, Shindo N, Scientific WHO, Technical advisory group for infectious H, (2020) COVID-19: what is next for public health? Lancet 395:542–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30374-3

Lai S, Ruktanonchai NW, Zhou L, Prosper O, Luo W, Floyd JR, Wesolowski A, Santillana M, Zhang C, Du X, Yu H, Tatem AJ (2020) Effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions to contain COVID-19 in China. Nature 585:410–413. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2293-x

Xiao J, Shiu EYC, Gao H, Wong JY, Fong MW, Ryu S, Cowling BJ (2020) Nonpharmaceutical measures for pandemic influenza in nonhealthcare settings-personal protective and environmental measures. Emerg Infect Dis 26:967–975. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2605.190994

Dadras O, Alinaghi SAS, Karimi A, MohsseniPour M, Barzegary A, Vahedi F, Pashaei Z, Mirzapour P, Fakhfouri A, Zargari G, Saeidi S, Mojdeganlou H, Badri H, Qaderi K, Behnezhad F, Mehraeen E (2021) Effects of COVID-19 prevention procedures on other common infections: a systematic review. Eur J Med Res 26:67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-021-00539-1

Khataee H, Scheuring I, Czirok A, Neufeld Z (2021) Effects of social distancing on the spreading of COVID-19 inferred from mobile phone data. Sci Rep 11:1661. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81308-2

Chen X, Huang H, Ju J, Sun R, Zhang J (2022) Impact of vaccination on the COVID-19 pandemic in U.S. states. Sci Rep 12:1554. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05498-z

Watson OJ, Barnsley G, Toor J, Hogan AB, Winskill P, Ghani AC (2022) Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis 22:1293–1302. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00320-6

Chow EJ, Uyeki TM, Chu HY (2023) The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on community respiratory virus activity. Nat Rev Microbiol 21:195–210. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-022-00807-9

Rubin R (2021) Influenza’s unprecedented low profile during COVID-19 pandemic leaves experts wondering what this flu season has in store. JAMA 326:899–900. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.14131

Jiang ML, Xu YP, Wu H, Zhu RN, Sun Y, Chen DM, Wang F, Zhou YT, Guo Q, Wu A, Qian Y, Zhou HY, Zhao LQ (2023) Changes in endemic patterns of respiratory syncytial virus infection in pediatric patients under the pressure of nonpharmaceutical interventions for COVID-19 in Beijing, China. J Med Virol 95:e28411. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.28411

Mosscrop LG, Williams TC, Tregoning JS (2022) Respiratory syncytial virus after the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic - what next? Nat Rev Immunol 22:589–590. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-022-00764-7

Kozlowski PA, Mantis NJ, Frey A (2022) Editorial: mucosal vaccination: strategies to induce and evaluate mucosal immunity. Front Immunol 13:905150. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.905150

Russell MW, Mestecky J (2022) Mucosal immunity: the missing link in comprehending SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission. Front Immunol 13:957107. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.957107

Russell MW, Moldoveanu Z, Ogra PL, Mestecky J (2020) Mucosal immunity in COVID-19: a neglected but critical aspect of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front Immunol 11:611337. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.611337

Lamers MM, Haagmans BL (2022) SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 20:270–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-022-00713-0

Kim HM, Lee EJ, Lee NJ, Woo SH, Kim JM, Rhee JE, Kim EJ (2021) Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on respiratory surveillance and explanation of high detection rate of human rhinovirus during the pandemic in the Republic of Korea. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 15:721–731. https://doi.org/10.1111/irv.12894

Dagan R, van der Beek BA, Ben-Shimol S, Greenberg D, Shemer-Avni Y, Weinberger DM, Danino D (2023) The COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity for unravelling the causative association between respiratory viruses and pneumococcus-associated disease in young children: a prospective study. EBioMedicine 90:104493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104493

Rybak A, Levy C, Angoulvant F, Auvrignon A, Gembara P, Danis K, Vaux S, Levy-Bruhl D, van der Werf S, Bechet S, Bonacorsi S, Assad Z, Lazzati A, Michel M, Kaguelidou F, Faye A, Cohen R, Varon E, Ouldali N (2022) Association of nonpharmaceutical interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic with invasive pneumococcal disease, pneumococcal carriage, and respiratory viral infections among children in France. JAMA Netw Open 5:e2218959. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.18959

McCullers JA (2006) Insights into the interaction between influenza virus and pneumococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev 19:571–582. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00058-05

Kandeel A, Fahim M, Deghedy O, Roshdy WH, Khalifa MK, Shesheny RE, Kandeil A, Naguib A, Afifi S, Mohsen A, Abdelghaffar K (2023) Resurgence of influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in Egypt following two years of decline during the COVID-19 pandemic: outpatient clinic survey of infants and children, October 2022. BMC Public Health 23:1067. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15880-9

Abu-Raya B, Vineta Paramo M, Reicherz F, Lavoie PM (2023) Why has the epidemiology of RSV changed during the COVID-19 pandemic? EClinicalMedicine 61:102089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102089

Cohen R, Ashman M, Taha MK, Varon E, Angoulvant F, Levy C, Rybak A, Ouldali N, Guiso N, Grimprel E (2021) Pediatric Infectious Disease Group (GPIP) position paper on the immune debt of the COVID-19 pandemic in childhood, how can we fill the immunity gap? Infect Dis Now 51:418–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idnow.2021.05.004

Treggiari D, Piubelli C, Formenti F, Silva R, Perandin F (2022) Resurgence of respiratory virus after relaxation of COVID-19 containment measures: a real-world data study from a regional hospital of Italy. Int J Microbiol 2022:4915678. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4915678

Bertran M, Amin-Chowdhury Z, Sheppard CL, Eletu S, Zamarreno DV, Ramsay ME, Litt D, Fry NK, Ladhani SN (2022) Increased incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease among children after COVID-19 pandemic, England. Emerg Infect Dis 28:1669–1672. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2808.220304

Farahat RA, Shaheen N, Kundu M, Shaheen A, Abdelaal A (2022) The resurfacing of hand, foot, and mouth disease: are we on the verge of another epidemic? Ann Med Surg (Lond) 81:104419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104419

Binns E, Koenraads M, Hristeva L, Flamant A, Baier-Grabner S, Loi M, Lempainen J, Osterheld E, Ramly B, Chakakala-Chaziya J, Enaganthi N, Simo Nebot S, Buonsenso D (2022) Influenza and respiratory syncytial virus during the COVID-19 pandemic: time for a new paradigm? Pediatr Pulmonol 57:38–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.25719

Dagan R, Danino D, Weinberger DM (2022) The pneumococcus-respiratory virus connection-unexpected lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 5:e2218966. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.18966

Gilligan P (2022) Impact of COVID-19 on infectious diseases and public health. American Society for Microbiology

McBride DL (2021) Social Distancing for COVID-19 Decreased infectious diseases in children. J Pediatr Nurs 58:100–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2021.02.018

Plantener E, Nanthan KR, Deding U, Damkjær M, Marmolin ES, Hansen LH, Petersen JJH, Pinilla R, Coia JE, Wolff DL, Song Z, Chen M (2023) Impact of COVID-19 restrictions on acute gastroenteritis in children: a regional, Danish, register-based study. Children 10:816

Kuitunen I, Artama M, Haapanen M, Renko M (2022) Urinary tract infections decreased in Finnish children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Pediatr 181:1979–1984. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-022-04389-9

Cesca L, Conversano E, Vianello FA, Martelli L, Gualeni C, Bassani F, Brugnara M, Rubin G, Parolin M, Anselmi M, Marchiori M, Vergine G, Miorin E, Vidal E, Milocco C, Orsi C, Puccio G, Peruzzi L, Montini G, Dall’Amico R, on the behalf of the Italian Society of Pediatric N (2022) How COVID-19 changed the epidemiology of febrile urinary tract infections in children in the emergency department during the first outbreak. BMC Pediatr 22:550. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03516-7

Hatoun J, Correa ET, Donahue SMA, Vernacchio L (2020) Social distancing for COVID-19 and diagnoses of other infectious diseases in children. Pediatrics 146 https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-006460

Cobo-Vazquez E, Aguilera-Alonso D, Carrasco-Colom J, Calvo C, Saavedra-Lozano J, Ped GASnWG (2023) Increasing incidence and severity of invasive group A streptococcal disease in Spanish children in 2019–2022. Lancet Reg Health Eur 27:100597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2023.100597

Cohen PR, Rybak A, Werner A, Bechet S, Desandes R, Hassid F, Andre JM, Gelbert N, Thiebault G, Kochert F, Cahn-Sellem F, Vie Le Sage F, Angoulvant PF, Ouldali N, Frandji B, Levy C (2022) Trends in pediatric ambulatory community acquired infections before and during COVID-19 pandemic: a prospective multicentric surveillance study in France. Lancet Reg Health Eur 22:100497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100497

Lamagni T, Guy R, Chand M, Henderson KL, Chalker V, Lewis J, Saliba V, Elliot AJ, Smith GE, Rushton S, Sheridan EA, Ramsay M, Johnson AP (2018) Resurgence of scarlet fever in England, 2014–16: a population-based surveillance study. Lancet Infect Dis 18:180–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30693-X

Chen Q, Allot A, Lu Z (2020) Keep up with the latest coronavirus research. Nature 579:193. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00694-1

Subbiah V (2023) The next generation of evidence-based medicine. Nat Med 29:49–58. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02160-z

Teixeira da Silva JA, Tsigaris P, Erfanmanesh M (2021) Publishing volumes in major databases related to COVID-19. Scientometrics 126:831–842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03675-3

Raynaud M, Goutaudier V, Louis K, Al-Awadhi S, Dubourg Q, Truchot A, Brousse R, Saleh N, Giarraputo A, Debiais C, Demir Z, Certain A, Tacafred F, Cortes-Garcia E, Yanes S, Dagobert J, Naser S, Robin B, Bailly E, Jouven X, Reese PP, Loupy A (2021) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on publication dynamics and non-COVID-19 research production. BMC Med Res Methodol 21:255. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-021-01404-9

Riccaboni M, Verginer L (2022) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on scientific research in the life sciences. PLoS One 17:e0263001. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263001

Sohrabi C, Mathew G, Franchi T, Kerwan A, Griffin M, Soleil CDMJ, Ali SA, Agha M, Agha R (2021) Impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on scientific research and implications for clinical academic training - a review. Int J Surg 86:57–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.12.008

Heaton PM (2020) The COVID-19 vaccine-development multiverse. N Engl J Med 383:1986–1988. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe2025111

Luxi N, Giovanazzi A, Capuano A, Crisafulli S, Cutroneo PM, Fantini MP, Ferrajolo C, Moretti U, Poluzzi E, Raschi E, Ravaldi C, Reno C, Tuccori M, Vannacci A, Zanoni G, Trifiro G, Ccg I (2021) COVID-19 Vaccination in pregnancy, paediatrics, immunocompromised patients, and persons with history of allergy or prior SARS-CoV-2 infection: overview of current recommendations and pre- and post-marketing evidence for vaccine efficacy and safety. Drug Saf 44:1247–1269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-021-01131-6

Folegatti PM, Bittaye M, Flaxman A, Lopez FR, Bellamy D, Kupke A, Mair C et al (2020) Safety and immunogenicity of a candidate Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus viral-vectored vaccine: a dose-escalation, open-label, non-randomised, uncontrolled, phase 1 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 20:816–826. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30160-2

Martin JE, Louder MK, Holman LA, Gordon IJ, Enama ME, Larkin BD, Andrews CA, Vogel L, Koup RA, Roederer M, Bailer RT, Gomez PL, Nason M, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ, Graham BS, Team VRCS (2008) A SARS DNA vaccine induces neutralizing antibody and cellular immune responses in healthy adults in a Phase I clinical trial. Vaccine 26:6338–6343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.09.026

Kumar A, Blum J, Le Thanh T, Havelange N, Magini D, Yoon IK (2022) The mRNA vaccine development landscape for infectious diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 21:333–334. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41573-022-00035-z

Barbier AJ, Jiang AY, Zhang P, Wooster R, Anderson DG (2022) The clinical progress of mRNA vaccines and immunotherapies. Nat Biotechnol 40:840–854. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-022-01294-2

Deng Z, Tian Y, Song J, An G, Yang P (2022) mRNA vaccines: the dawn of a new era of cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol 13:887125. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.887125

Miao L, Zhang Y, Huang L (2021) mRNA vaccine for cancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer 20:41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-021-01335-5

Summan A, Nandi A, Shet A, Laxminarayan R (2023) The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on routine childhood immunization coverage and timeliness in India: retrospective analysis of the National Family Health Survey of 2019–2021 data. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia 8:100099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lansea.2022.100099

Lavie M, Lavie I, Laskov I, Cohen A, Grisaru D, Grisaru-Soen G, Michaan N (2023) Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on human papillomavirus vaccine uptake in Israel. J Low Genit Tract Dis 27:168–172. https://doi.org/10.1097/LGT.0000000000000729

Raut A, Huy NT (2022) Impediments to child education, health and development during the COVID-19 pandemic in India. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia 1:100005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lansea.2022.04.001

Hotez PJ (2021) Mounting antiscience aggression in the United States. PLoS Biol 19:e3001369. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001369

Karafillakis E, Van Damme P, Hendrickx G, Larson HJ (2022) COVID-19 in Europe: new challenges for addressing vaccine hesitancy. Lancet 399:699–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00150-7

Wilkinson E (2022) Is anti-vaccine sentiment affecting routine childhood immunisations? BMJ 376:o360. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.o360

Patel M, Lee AD, Redd SB, Clemmons NS, McNall RJ, Cohn AC, Gastanaduy PA (2019) Increase in measles cases - United States, January 1-April 26, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 68:402–404. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6817e1

SeyedAlinaghi S, Karimi A, Mojdeganlou H, Alilou S, Mirghaderi SP, Noori T, Shamsabadi A, Dadras O, Vahedi F, Mohammadi P, Shojaei A, Mahdiabadi S, Janfaza N, Keshavarzpoor Lonbar A, Mehraeen E, Sabatier JM (2022) Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on routine vaccination coverage of children and adolescents: a systematic review. Health Sci Rep 5:e00516. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.516

Neves FPG, Mestrovic T, Pinto TCA (2023) Editorial: drug resistance in maternal and paediatric bacterial and fungal infections: is COVID-19 changing the landscape. Front Microbiol 14:1177669. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1177669

Fontana C, Favaro M, Minelli S, Bossa MC, Altieri A (2021) Co-infections observed in SARS-CoV-2 positive patients using a rapid diagnostic test. Sci Rep 11:16355. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95772-3

Dutcher L, Li Y, Lee G, Grundmeier R, Hamilton KW, Gerber JS (2022) COVID-19 and antibiotic prescribing in pediatric primary care. Pediatrics 149 https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-053079

Kronman MP, Gerber JS, Grundmeier RW, Zhou C, Robinson JD, Heritage J, Stout J, Burges D, Hedrick B, Warren L, Shalowitz M, Shone LP, Steffes J, Wright M, Fiks AG, Mangione-Smith R (2020) Reducing antibiotic prescribing in primary care for respiratory illness. Pediatrics 146 https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0038

Wittman SR, Martin JM, Mehrotra A, Ray KN (2023) Antibiotic receipt during outpatient visits for COVID-19 in the US, From 2020 to 2022. JAMA Health Forum 4:e225429. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.5429

Malik SS, Mundra S (2022) Increasing consumption of antibiotics during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for patient health and emerging anti-microbial resistance. Antibiotics (Basel) 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12010045

Kariyawasam RM, Julien DA, Jelinski DC, Larose SL, Rennert-May E, Conly JM, Dingle TC, Chen JZ, Tyrrell GJ, Ronksley PE, Barkema HW (2022) Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis (November 2019-June 2021). Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 11:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-022-01085-z

Funding

No funding has been received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Moshe Shmueli, Idan Lender, and Shalom Ben-Shimol have all contributed equally to the conception and design of the review, drafted and revised the manuscript and approve its publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Shalom Ben-Shimol has received within the last 35 months grants by Pfizer. He serves as scientific consultant and on the review board of Pfizer and MSD, and belongs to the speaker bureau of Pfizer, MSD, and GSK. The other authors do not report any conflict of interest.

Additional information

Communicated by Tobias Tenenbaum

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Shmueli, M., Lendner, I. & Ben-Shimol, S. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the pediatric infectious disease landscape. Eur J Pediatr 183, 1001–1009 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-05210-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-05210-x