Abstract

To investigate the biological and socioeconomic factors associated with developmental attainment in socioeconomically disadvantaged children. This study was performed at the Dr. Sami Ulus Children’s Health and Diseases Training and Research Hospital, between January and December 2010. The effects of biological, socioeconomic risk factors on developmental delay were investigated in 692 children (3 months–5 years) using the Denver II. Low-level maternal education (odds ratio [OR], 11.118; 95 % CI, 4.211–29.351), low-level paternal education (OR, 2.107; 95 % CI, 1.333–3.331), low-level household income (OR, 2.673; 95 % CI, 1.098–2.549), and ≥3 children in the family (OR, 1.871; 95 % CI, 1.206–2.903) were strongly associated with abnormal on Denver II; biological risk factors, including birth weight, gestational age at birth, and maternal age at birth <20 years, were correlated with suspect on Denver II results based on univariate analysis. Low-level maternal education (OR, 6.281; 95 % CI, 2.193–17.989), premature birth (32–36 weeks of gestation; OR, 0.535; 95 % CI, 0.290–0.989) were strongly associated with abnormal on Denver II results, and low-level paternal education (OR, 3.088; 95 % CI, 1.521–6.268), low-level household income (OR, 1.813; 95 % CI, 1.069–3.077), low birth weight (<1,500 g; OR, 3.003; 95 % CI, 1.316–6.854), premature birth (27–31 weeks of gestation; OR, 2.612; 95 % CI, 1.086–6.286), and maternal age at birth <20 years (OR, 3.518; 95 % CI, 1.173–10.547) were strongly associated with suspect on Denver II results based on multivariate analysis.

Conclusion

Socioeconomic risk factors were observed to be as important as biological risk factors in the development of children aged 3 months–5 years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The period from birth to 5 years is critical for the development of language, cognitive, emotional, social, behavioral, and physical skills [3, 16]. Early childhood is the most effective time to ensure that all children develop their full potential. Developmental disorders in children range from subtle learning disabilities to severe cognitive/motor impairment. Early recognition of developmental problems is important for timely intervention [12, 13, 19]; however, it was reported that only 30 % of such cases are identified before they begin school [20].

The risk factors associated with developmental problems have been divided into environmental and biological categories, and are often synergistic. A longitudinal population-based study reported the importance of risk factor profiles that change over time. The relative significance of risk factors for developmental problems changes during the first few years of life; biological factors becoming less important and psychosocial factors become more important [23]. Chronic exposure to poverty and its associated factors precludes presumably 200 million children in developing countries from achieving their full developmental and cognitive potential; however, there are few national data on the development of young children in developing countries [11].

Because many studies have documented the negative effects of social and economic deprivation on children [4, 6, 7, 17], developmental screening is critically needed to identify children with developmental problems early in life, especially socially and economically disadvantaged children. The aim of the present study was to determine the etiological factors for developmental delay up to age 5 years and their cumulative risk at a single tertiary center in Turkey.

Materials and methods

Participants

The study included 692 children aged 3 months–5 years that presented to Dr. Sami Ulus Children’s Health and Diseases Training and Research Hospital, Ankara, Turkey, and were administered the Denver II between January 2010 and December 2010. Only children living with both parents were included in the study. Children with vision or hearing impairment, a diagnosis of a progressive neurodegenerative disorder, those participating in a rehabilitation program, and the children with known mental and/or motor developmental disabilities were excluded from the study. The study protocol was approved by the Dr. Sami Ulus Children’s Health and Diseases Training and Research Hospital Ethics Committee, and was performed according to the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent was obtained from the parents before data collection.

Child and parent questionnaires

Demographic data on the children, including gender, age, gestational age at birth, and birth weight were collected. Children were grouped according to age (3–24, 25–48, and 49–60 months), gestational age at birth (27–31 weeks, 32–36 weeks, and ≥37 weeks), and birth weight (≤1,500 g, 1,501–2,500 g, and ≥2,501 g). Data on parental level of education, monthly household income, maternal age at birth, and number of siblings were collected. Parental level of education was categorized as illiterate, primary school (8-year compulsory schooling) graduate, and post-primary school (high school and college) graduate; monthly household income was evaluated in two categories as below or higher the national poverty threshold (870 Turkish Liras) [approximately $500]; maternal age at birth as <20 years, 20–40 years, and >40 years; and total number of children as ≤2 and ≥3. Parental level of education, monthly income, and number of children were considered environmental risk factors, and gestational age at birth, birth weight, and maternal age at birth were considered biological risk factors.

Screening test procedure

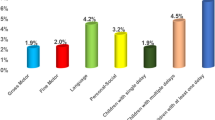

Denver II was administered to all the children by the same child development specialist (EA), who was blinded to history of the cases. Denver II is used to screen children from birth to age 6 years and includes 125 items in four domains: personal–social, language, fine motor skills, and gross motor skills. Denver II has inter-rater and test–retest reliability of 0.99 ± 0.01 and 0.90 ± 0.12, respectively. Denver II results were interpreted as follows: ≥2 delayed items: abnormal; 1 delay and 1 caution: suspected; and no delay or 1 caution: normal. The Turkish version of Denver II was reported to be valid and reliable for use in Turkey by Durmazlar et al. [8]. Premature born children younger than 2 years of age were tested after calculating the corrected age.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS v.11.5 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics are shown as the number of cases and percentage. The potential of risk factors to have statistically significant effects on suspected or abnormal development (according to Denver II) was evaluated via univariate multinomial logistic regression analysis. The odds ratio (OR) and 95 % confidence interval (CI) for each independent variable were also calculated. Determination of the most predictive factors that differentiated normal-suspect and normal-abnormal was performed via multivariate multinomial logistic regression. Adjusted ORs were calculated regarding all variables in the model. Any variable in the univariable analysis with a P value <0.25 was accepted as a candidate for the multivariable model, along with all variables of known clinical importance. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In all, 81.9 % of the children were aged 3–24 months at the time of interview, 54.6 % were male, and 63.3 % of the children were born full term; 15.3 % of the mothers and 20.5 % of the fathers are post-primary school graduates and 75.7 % of the families had low household income. Demographic, biological, and socioeconomic data for the children and parents are shown in Table 1. Among the 692 children, 361 (52.2 %) had normal, 138 (19.9 %) suspect, and 193 (27.9 %) abnormal on Denver II results (Table 2); there were not any differences between genders.

Univariate multinomial logistic regression analysis of the potential risk factors showed that the probability of suspect on Denver II results of the children of illiterate mothers was significantly higher than in those whose mother was a post-primary school graduate (OR, 3.706; 95 % CI, 1.181–11.6332; P = 0.025). The probability of abnormal on Denver II results in the children of illiterate and primary school graduate mothers was significantly higher than in those whose mother was a post-primary school graduate (OR, 11.118; 95 % CI, 4.211–29.351; P < 0.001 and OR, 2.336; 95 % CI, 1.330–4.105; P = 0.003, respectively). The probability of suspect and abnormal on Denver II results in the children of fathers with a low-level education (illiterate/primary school graduate) was significantly higher than in those whose father was a post-primary school graduate (OR, 3.056; 95 % CI, 1.704–5.480; P < 0.001 and OR, 2.107; 95 % CI, 1.333–3.331; P < 0.001, respectively).

The probability of suspect and abnormal on Denver II results in the children of families with a low household income was significantly higher (OR, 1.854; 95 % CI, 1.137–3.024; P = 0.013; and OR, 2.673; 95 % CI, 1.098–2.549; P = 0.017, respectively). As compared to the children from families with ≤2 children, the probability of suspect on Denver II results in the children of families with ≥3 children did not differ significantly (P = 0.795) and the probability of abnormal on Denver II results was significantly higher (OR, 1.871; 95 % CI, 1.206–2.903; P = 0.005).

The probability of suspect on Denver II results in the children with a gestational age at birth of 27–31 and 32–36 weeks was significantly higher than in those with a gestational age of ≥37 weeks (OR, 5.944; 95 % CI, 3.489–10.125; P < 0.001 and OR, 2,133; 95 % CI, 1.314–3.462; P = 0.002, respectively). Gestational age at birth did not have a significant effect on the probability of abnormal on Denver II results (P > 0.05). The probability of suspect on Denver II results in those with a birth weight of 1,501–2,500 g and ≤1,500 g was significantly higher than in those with a birth weight ≥2,501 g (OR, 2.476; 95 % CI, 1.453–4.221; P < 0.001 and OR, 5.519; 95 % CI, 3.347–9.099; P < 0.001, respectively). Birth weight did not have a significant effect on the probability of abnormal on Denver II results (P > 0.05).

The probability of suspect on Denver II results in the children of mothers aged <20 years at birth was significantly higher than in those whose mother was aged 20–40 years (OR, 2.760; 95 % CI, 1.014–7.517; P = 0.047). There was not a significant effect of maternal age at birth on the probability of abnormal on Denver II results (P > 0.05; Table 3).

When the cumulative effects of all risk factors likely to be associated with suspect or abnormal on Denver II results were analyzed via multivariate multinomial logistic regression analysis, the most predictive factor for abnormal on Denver II results was an illiterate mother (OR, 6.281; 95 % CI, 2.193–17.989; P < 0.001), followed by gestational age at birth of 32–36 weeks (OR, 0.535; 95 % CI, 0.290–0.989; P = 0.046). The most predictive factor of suspect on Denver II results was a father with low-level education (OR, 3.088; 95 % CI, 1.521–6.268; P = 0.002), followed by birth weight ≤1,500 g (OR, 3.003; 95 % CI, 1.316–6.854; P = 0.009), maternal age at birth <20 years (OR, 3.518; 95 % CI, 1.173–10.547; P = 0.025), low household income (OR, 1.813; 95 % CI, 1.069–3.077; P = 0.027), and gestational age at birth of 27–31 weeks (OR, 2.612; 95 % CI, 1.086–6.286; P = 0.032; Table 4).

Discussion

The present findings show that socioeconomic factors of the family had a greater effect than biological factors on the children’s development up to age 5 years. Our hospital is a multidisciplinary reference center serving a region with a relatively low socioeconomic level. Although 8-year primary school education is compulsory in Turkey, 5.2 % of the mothers and 1.6 % of the fathers in the study were illiterate. Only 15.3 % of the mothers and 20.5 % of the fathers had post-primary school education. As low-level education is highly associated with low household income, approximately 75 % of the families had an income below the national poverty level. The Denver II abnormal results rate was high (27.9 %), which might have been due to the high number of socioeconomically disadvantaged children and prematurely born children included in the study. It is well known that many risk factors are implicated in the etiology of developmental impairment in young children, including biological, social, and environmental [4, 5, 15, 17, 18]; therefore, determining which risk factors are important for development in children during the first 5 years in Turkey, and early intervention for children developmentally at risk and optimal allocation of limited resources are essential.

In the present study, univariate multinomial logistic regression analysis of the effects of biological risk factors, such as maternal age at birth, premature birth, and low birth weight, showed that they were associated with the probability of suspect on Denver II, but were not associated with the probability of abnormal results. In addition, socioeconomic risk factors had a significant effect on the probability of suspect and abnormal on Denver II results. These results are consistent with To et al. [23], who reported that socioeconomic risk factors might be more important than biological risk factors.

Maternal education is defined as an important factor in child development in the previous studies [1, 23]. The present study observed that maternal level of education was associated with the probability of suspect and abnormal on Denver II results. The probability of suspect and abnormal on Denver II results in the children of illiterate mothers was 3.7-fold and 11.1-fold greater, respectively, than in those whose mother was a post-primary school graduate. The probability of abnormal on Denver II results in the children whose mother was a primary school graduate was 2.3-fold greater than in those whose mother was a post-primary school graduate. Besides maternal education, the present study observed that paternal education was also associated with the probability of suspect and abnormal on Denver II results. The probability of suspect and abnormal on Denver II results in the children whose father had low-level education (illiterate/primary school graduate) was 3-fold and 2.107-fold greater, respectively, than in those whose father was post-primary school graduate.

Developmental interventions during early childhood, such as parental education and preschool education, are important for improving developmental outcomes in children in low-income and middle-income countries [10]; however, a UK study reported that young children with delayed development were likely to be exposed to repeated socioeconomic disadvantage [9]. The present study observed that the rate of suspect and abnormal on Denver II results was higher in the children from families with low monthly income.

Abubakar et al. [1] reported that as a mother’s gravidity increases the risk of poor developmental outcome in subsequent children increases. Similarly, the present study observed that the probability of abnormal on Denver II results in the children from families with ≥3 children was approximately 2-fold greater than in those from families with ≤2 children. This may be due to decrease in the quality and quantity of the time allocated for each child in large and crowded families.

When all risk factors associated with the probability of abnormal on Denver II results were analyzed via multivariate multinomial logistic regression analysis in the present study, in other words following adjustment for other risk factors, maternal level of education was observed to be the most important factor. As previously reported, maternal level of education is an important factor in the development of children. Even in premature infants that are biologically at risk, a literate mother positively affects the development of the child [22]. In the present study, premature birth had no effect on the probability of abnormal on Denver II results, based on univariate multinomial logistic regression analysis, whereas multivariate multinomial logistic regression analysis showed that it was a risk factor (P = 0.046).

The most predictive factor of suspect on Denver II results was low-level paternal education. Although earlier studies emphasized the importance of maternal education, the present study observed that paternal education was also an important factor for child development. Other factors in the present study associated with the probability of suspect on Denver II results were birth weight ≤1,500 g, maternal age at birth <20 years, low household income, and gestational age at birth of 27–31 weeks. Similar to the present study, Halpern et al. [14] reported that low birth weight and low household income were associated with suspected developmental delay. In fact, “suspect” result is not abnormal. Some of these children could turn out to be normal and the others, abnormal. This depends on the variable environmental and biological factors of the population. Early detection of these children by developmental screening tests and early intervention may provide better results.

With improvements in the quality of newborn intensive care and child development units in Turkey, early developmental assessment is more frequently performed in children with biological risk factors, such as premature birth and low birth weight, whereas the effects of socioeconomic risk factors remain overlooked. There are relatively few studies concerning the effects of environmental factors on child development in Turkey [2, 8]. Nonetheless, in regions with environmental risk factors such as low socioeconomic status early developmental assessment of children is crucial. Additionally, low socioeconomic status is a risk factor for developmental delay in children, and poverty and lack of education may reduce parental access to information about interventions for their children [21]. Examination of those factors that support development during infancy is important for the design of effective interventions for infants at risk of developmental problems. The limitation of the study is not being able to be a longitudinal study.

Conclusion

The present study’s findings show that socioeconomic factors might be more important than biological factors for the development of children up to 5 years of age. Besides the well-known effect of maternal education, paternal education was a crucial factor in the development of children.

References

Abubakar A, Holding P, Van de Vijver FJ, Newton C, Van Baar A (2010) Children at risk for developmental delay can be recognised by stunting, being underweight, ill health, little maternal schooling or high gravidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 51:652–659

Bayoglu BU, Bakar EE, Kutlu M, Karabulut E, Anlar B (2007) Can preschool developmental screening identify children at risk for school problems? Early Hum Dev 83:613–617

Bennett FC, Guralnick MJ (1991) Effectiveness of developmental intervention in the first 5 years of life. Pediatr Clin North Am 38:1513–1528

Bradley RH, Corwyn RF (2002) Socioeconomic status and child development. Annu Rev Psychol 53:371–399

Bradley RH, Corwyn RF, McAdoo HP, Coll CG (2001) The home environments of children in the United States part I: variations by age, ethnicity, and poverty status. Child Dev 72:1844–1867

Chiu SH, DiMarco MA (2010) A pilot study comparing two developmental screening tools for use with homeless children. J Pediatr Health Care 24:73–80

Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov PK (1994) Economic deprivation and early childhood development. Child Dev 65:296–318

Durmazlar N, Ozturk C, Ural B, Karaagaoglu E, Anlar B (1998) Turkish children’s performance on Denver II: effect of sex and mother’s education. Dev Med Child Neurol 40:411–416

Emerson E, Graham H, McCulloch A, Blacher J, Hatton C, Llewellyn G (2009) The social context of parenting 3-year-old children with developmental delay in the UK. Child Care Health Dev 35:63–70

Engle PL, Fernald LC, Alderman H, Behrman J, O’Gara C, Yousafzai A, de Mello MC, Hidrobo M, Ulkuer N, Ertem I, Iltus S (2011) Strategies for reducing inequalities and improving developmental outcomes for young children in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 378:1339–1353

Grantham-McGregor S, Cheung YB, Cueto S, Glewwe P, Richter L, Strupp B (2007) Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. Lancet 369:60–70

Guralnick MJ (2010) Early intervention approaches to enhance the peer-related social competence of young children with developmental delays: a historical perspective. Infants Young Child 23:73–83

Guralnick MJ (2011) Why early intervention works: a systems perspective. Infants Young Child 24:6–28

Halpern R, Barros AJ, Matijasevich A, Santos IS, Victora CG, Barros FC (2008) Developmental status at age 12 months according to birth weight and family income: a comparison of two Brazilian birth cohorts. Cad Saude Publica 24(Suppl 3):S444–S450

Hediger ML, Overpeck MD, Ruan WJ, Troendle JF (2002) Birthweight and gestational age effects on motor and social development. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 16:33–46

Hertzman C, Wiens M (1996) Child development and long-term outcomes: a population health perspective and summary of successful interventions. Soc Sci Med 43:1083–1095

Lugo-Gil J, Tamis-LeMonda CS (2008) Family resources and parenting quality: links to children’s cognitive development across the first 3 years. Child Dev 79:1065–1085

Lung FW, Shu BC, Chiang TL, Lin SJ (2011) Maternal mental health and childrearing context in the development of children at 6, 18 and 36 months: a Taiwan birth cohort pilot study. Child Care Health Dev 37:211–223

McCarton CM, Brooks-Gunn J, Wallace IF, Bauer CR, Bennett FC, Bernbaum JC, Broyles RS, Casey PH, McCormick MC, Scott DT, Tyson J, Tonascia J, Meinert CL (1997) Results at age 8 years of early intervention for low-birth-weight premature infants. The infant health and development program. JAMA 277:126–132

Palfrey JS, Singer JD, Walker DK, Butler JA (1987) Early identification of children’s special needs: a study in five metropolitan communities. J Pediatr 111:651–659

Porterfield SL, McBride TD (2007) The effect of poverty and caregiver education on perceived need and access to health services among children with special health care needs. Am J Public Health 97:323–329

Resegue R, Puccini RF, Silva EM (2008) Risk factors associated with developmental abnormalities among high-risk children attended at a multidisciplinary clinic. Sao Paulo Med J 126:4–10

To T, Guttmann A, Dick PT, Rosenfield JD, Parkin PC, Tassoudji M, Vydykhan TN, Cao H, Harris JK (2004) Risk markers for poor developmental attainment in young children: results from a longitudinal national survey. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 158:643–649

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Scott B. Evans for English language editing.

Conflict of interest

We as the authors state that there is no conflict of interest and the work is not a part of any commercial organization.

Ethical approval

Dr Sami Ulus Children’s Health and Diseases Training and Research Hospital (no. B.1041SM4060017, 20.05.09*3425).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ozkan, M., Senel, S., Arslan, E.A. et al. The socioeconomic and biological risk factors for developmental delay in early childhood. Eur J Pediatr 171, 1815–1821 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-012-1826-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-012-1826-1