Abstract

In 1995, a new form of vitamin K prophylaxis with two oral doses of 2 mg mixed micellar phylloquinone (Konakion MM) on the 1st and 4th day of life was introduced in Switzerland. It was hoped that this new galenic preparation of phylloquinone would protect infants with insufficient or absent bile acid excretion from late vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB). Subsequently, the occurrence of VKDB was monitored prospectively between July 1, 1995 and June 30, 2001 with the help of the Swiss Paediatric Surveillance Unit (SPSU). Over a period of 6 years (475,000 deliveries), there were no cases of early (<24 h of age), one case of classical (2–7 days of life), and 18 cases of late (1–12 weeks) VKDB fulfilling standard case definitions. In 13/18 patients with late VKDB there was pre-existing liver disease and in 4/18 patients, parents had refused prophylaxis. The incidence of late VKDB for infants with completed Konakion MM prophylaxis was 2.31/100,000 (95% CI: 1.16–4.14) and for the entire population 3.79/100,000 (95% CI: 2.24–5.98). There was only one case of late VKDB after complete prophylaxis in an infant without underlying liver disease. Conclusion: two oral doses of 2 mg of a mixed micellar vitamin K preparation failed to abolish VKDB. The recommendations for vitamin K prophylaxis in Switzerland have therefore been changed to include a third dose at 4 weeks of age. Starting on January 1, 2004, the incidence of vitamin K deficiency bleeding will again be monitored prospectively by the Swiss Paediatric Surveillance Unit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 1994, Switzerland was the first country to license a newly developed preparation of phylloquinone in the form of mixed micelles of bile acids and lecithin for intravenous, intramuscular and oral use in newborns (Konakion MM paediatric, Roche Pharma (Schweiz) AG). Based on the results of two pharmacokinetic studies, this preparation was suggested for prophylaxis of vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB) in neonates [14, 16]. In particular, it was expected that infants with transient or not yet detected cholestatic disease would have improved enteral absorption and therefore be better protected from late VKDB [1]. It was recommended that the previously used lipid soluble preparation should be replaced by Konakion MM [15]. The dose and the dosing interval remained unchanged: 2 mg were to be given orally on the 1st and 4th day of life.

This report summarises the results of a prospective national 6-year surveillance to study the influence of these new guidelines on the incidence of VKDB.

Subjects and methods

Data collection extended over a period of 6 years from July 1, 1995 until June 30, 2001. Information regarding the incidence of VKDB was prospectively collected on a monthly basis from all 39 paediatric hospitals with the help of the Swiss Paediatric Surveillance Unit (SPSU) [21]. Reported cases were validated with a detailed questionnaire. This instrument is comparable to surveillance units in the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands, Canada, New Zealand and Australia (http://www.inopsu.com). All of theses countries use the same case definition of VKDB which was proposed at a consensus conference in 1994 [18]. Late VKDB is defined by the following criteria: (1) occurrence between the 2nd and the completed 12th week of life, (2) Quick values ≤15%, INR ≥4, prothrombin time ≥4x control value, and (3) at least one of the following: normal or increased platelet count, normal fibrinogen and absence of fibrin degradation products, return of prothrombin time to normal values after vitamin K administration.

Six months after the publication of the new guidelines, their acceptance among health care workers was verified and an interim analysis of their impact on the incidence of VKDB was carried out after 3 years [17]. In the present report, our 6-year experience is summarised and the incidence of VKDB is compared with historical controls from Switzerland as well as reported incidence figures from other countries.

The 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated according to Clopper-Pearson and the chi-squared test was used for comparison of different study populations.

Results

A survey of all obstetric units in Switzerland in 1995 showed that 99% of all newborn infants were receiving vitamin K prophylaxis according to the guidelines; in 5% of babies the new preparation was given parenterally [17]. The response rate to the monthly SPSU inquiries as well as to the questionnaires was 100%.

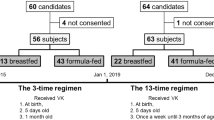

Of 25 reports, 19 met the case definition of VKDB. A total of six patients had to be excluded (Fig. 1). Of the 18 confirmed late cases, 11 had received their vitamin K prophylaxis in accordance with the recommendations. All patients were partially (n=2) or fully (n=16) breast-fed.

There was no case of early VKDB (i.e. onset before 24 h of age). One patient had mild gastrointestinal bleeding on the 2nd day of life with a Quick value of 10%; this case was considered to represent classical VKDB (i.e. onset between 24 h to the end of day 7 of life). The remaining 18 cases were confirmed late VKDB. The bleeding episodes in these patients occurred at a median age of 6 weeks (range 3–12 weeks). Six patients had intracranial haemorrhages of which two were fatal. The other four patients developed significant sequelae. Details are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. One bleeding episode (case 10) occurred in a fully breast-fed infant during the 5th week of life after correct prophylaxis. This case must be classified as idiopathic with no factor predisposing to vitamin K deficiency and thus represents the only true failure of prophylaxis. In 13/18 patients, bleeding episodes were the first manifestations of underlying liver disease with cholestasis.

Overall, the incidence of late VKDB was 3.79/100,000 (95% CI: 2.24–5.98). If patients who had received no or incomplete prophylaxis or prophylaxis with the old fat-soluble preparation were excluded, the incidence was 2.31/100,000 (95% CI: 1.16–4.14).

Discussion

With a two-dose-regimen of vitamin K prophylaxis used in Switzerland since 1994, idiopathic late VKDB, i.e. bleeding episodes occurring in infants without underlying disease after correctly given prophylaxis, has become extremely rare (0.2/100,000; 95% CI: 0.005–1.1). However, in October 1994, representatives of countries with national surveillance programmes argued that “if the baby bleeds before diagnosis of a liver disease, the vitamin K prophylaxis has failed” [18]. Clearly, this goal was not achieved in Switzerland with the introduction of a two-dose-regimen of mixed micellar vitamin K during the 1st week of life. Prospective surveillance showed that the incidence of late VKDB was 2.31/100,000 (95% CI: 1.16–4.14). In the years 1993–1994, when the Cremaphor-based lipid soluble preparation was used, the incidence was slightly higher with 4.13/100,000 (95% CI: 1.34–9.64) [13]; however, this difference is not statistically significant (P=0.247) and comparison with historical controls is of somewhat limited value since early diagnosis of cholestatic liver disease may have improved. In addition, 30% of the bleeding episodes represented intracranial haemorrhages with severe consequences for the patients (Table 1).

Recently, Pereira et al. [11] have shown that the intestinal absorption of mixed micellar vitamin K is unreliable in infants with conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia. In this study, serum concentrations of vitamin K after an oral dose of 2 mg were compared with serum concentrations achieved by the administration of 1 mg intravenously. This represents a much lower oral dose than the 10 mg used by Amedee-Manesme et al. [1] in their frequently cited study which formed the basis for the hypothesis that mixed micellar vitamin K is better absorbed even in the absence of bile acids.

There is an ongoing debate about the most appropriate regimen for prophylaxis of late VKDB [8, 19]. Intramuscular administration of 1 mg of vitamin K shortly after delivery must be considered the gold standard since it prevents all forms of VKDB almost entirely [5, 12]. The reasons for the increased benefit with intramuscular administration of vitamin K following birth are not clear, but are possibly related to storage at the site of injection with slow release over the first weeks of life [10].

Comparable but not complete protection can be achieved with vitamin K fortified formula or daily oral supplementation with 25 µg of vitamin K of fully breast-fed infants [3, 4]. In Denmark, weekly administration of 1 mg of vitamin K in fully breast-fed infants up to the age of 3 months has yielded good results [7]. In a randomised trial, Greer and colleagues [6] have shown that three 2 mg oral doses of mixed micellar vitamin K (birth, 7, 30 days of life) resulted in higher plasma concentrations (at 14 and 56 days) than those measured after a single 1 mg intramuscular dose at birth. In Germany, three oral doses of 2 mg of Konakion at birth, 7 and 30 days of life are currently recommended. Both Cremophor-based lipid soluble and mixed micellar products are available. The incidence of late VKDB in children with cholestatic disease was independent of the type of vitamin K preparation used. It has been estimated that with this three-dose-regimen, the incidence of late VKDB after complete prophylaxis with Konakion MM is 0.44/100,000 (95% CI: 0.19–0.87) and with lipid soluble vitamin K preparations 0.76/100,000 (95% CI: 0.36–1.39) [20]. This difference is not statistically significant (P=0.276).

We are worried that the intramuscular administration of vitamin K would not be acceptable to many parents and some health care professionals in Switzerland, possibly resulting in a surge of late VKDB. In this context, it is important to note that even in countries which recommend intramuscular vitamin K prophylaxis, the incidence of late VKDB is not zero (Grenier D, personal communication). Frequent oral administration of small doses of vitamin K only to fully breast-fed infants may be too complicated and could fail due to poor compliance. Prophylactic measures must follow simple rules and should be accessible to all, otherwise they can cause confusion [2, 9]. Therefore, we have decided on a pragmatic and mnemotechnically simple revision of the Swiss guidelines: Konakion MM 2 mg p.o. at the age of 4 h, 4 days and 4 weeks for all infants who are normally fed. The dose on the 4th day coincides with blood sampling for newborn screening. The third dose at 4 weeks of age will be administered during the well baby examination which has recently been approved by the Swiss Office for Social Security. Exceptions to this rule are included in the new guidelines (http://www.neonet.ch). The impact of the new guidelines will once again be evaluated with a prospective surveillance project starting January 1, 2004.

Abbreviations

- CI :

-

confidence interval

- SPSU :

-

Swiss Paediatric Surveillance Unit

- VKDB :

-

vitamin K deficiency bleeding

References

Amedee-Manesme O, Lambert WE, Alagille D, De Leenheer AP (1992) Pharmacokinetics and safety of a new solution of vitamin K1(20) in children with cholestasis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 14: 160–165

Ansell P, Roman E, Fear NT, Renfrew MJ (2001) Vitamin K policies and midwifery practice: questionnaire survey. BMJ 322: 1148–1152

Cornelissen EA, Kollee LA, van Lith TG, Motohara K, Monnens LA (1993) Evaluation of a daily dose of 25 micrograms vitamin K1 to prevent vitamin K deficiency in breast-fed infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 16: 301–305

Cornelissen EA, Hirasing RA, Monnens LA (1996) Prevalence of hemorrhages due to vitamin K deficiency in The Netherlands, 1992–1994. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 140: 935–937

Cornelissen M, von Kries R, Loughnan P, Schubiger G (1997) Prevention of vitamin K deficiency bleeding: efficacy of different multiple oral dose schedules of vitamin K. Eur J Pediatr 156: 126–130

Greer FR, Marshall SP, Severson RR et al (1998) A new mixed micellar preparation for oral vitamin K prophylaxis: randomised controlled comparison with an intramuscular formulation in breast fed infants. Arch Dis Child 79: 300–305

Hansen KN, Ebbesen F (1996) Neonatal vitamin K prophylaxis in Denmark: three years’ experience with oral administration during the first three months of life compared with one oral administration at birth. Acta Paediatr 85: 1137–1139

Hey E (2003) Vitamin K--what, why, and when. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 88: F80–F83

Jonville-Bera AP, Autret E (1997) Study of the use of vitamin K in neonates in France. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 52: 333–337

Loughnan P, McDougall P (1994) The duration of vitamin K1 efficacy: is intramuscular vitamin K1 acting as a depot preparation? In: Sutor AH, Hathaway EW (eds) Vitamin K in infancy. Schattauer Verlag, Stuttgart, pp 225–234

Pereira SP, Shearer MJ, Williams R, Mieli-Vergani G (2003) Intestinal absorption of mixed micellar phylloquinone (vitamin K1) is unreliable in infants with conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia: implications for oral prophylaxis of vitamin K deficiency bleeding. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 88: F113–F118

Puckett RM, Offringa M (2000) Prophylactic vitamin K for vitamin K deficiency bleeding in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: CD002776

Schubiger G, Tönz O (1994) Epidemiological data on vitamin K prophylaxis in Switzerland. In: Sutor AH, Hathaway WE (eds) Vitamin K in infancy. Schattauer Verlag, Stuttgart, pp 177–178

Schubiger G, Tönz O, Grüter J, Shearer MJ (1993) Vitamin K1 concentration in breast-fed neonates after oral or intramuscular administration of a single dose of a new mixed-micellar preparation of phylloquinone. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 16: 435–439

Schubiger G, Roulet M, Laubscher B (1994) Vitamin K1-Prophylaxe bei Neugeborenen: Neue Empfehlungen. Schweizerische Ärztezeitung 75: 2036–2037

Schubiger G, Grüter J, Shearer MJ (1997) Plasma vitamin K1 and PIVKA-II after oral administration of mixed-micellar or cremophor EL-solubilized preparations of vitamin K1 to normal breast-fed newborns. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 24: 280–284

Schubiger G, Stocker C, Bänziger O, Laubscher B, Zimmermann H (1999) Oral vitamin K1 prophylaxis for newborns with a new mixed-micellar preparation of phylloquinone: 3 years experience in Switzerland. Eur J Pediatr 158: 599–602

Tripp J, Cornelissen M, Loughnan P, McNinch A, Schubiger G, von Kries R (1994) Suggested protocol for the reporting of prospective studies of vitamin K deficiency bleeding. In: Sutor HA, Hathaway WE (eds) Vitamin K in infancy. Schattauer Verlag, Stuttgart, pp 395–401

Tripp JH, McNinch AW (1998) The vitamin K debacle: cut the Gordian knot but first do no harm. Arch Dis Child 79: 295–297

Von Kries R, Hachmeister A, Gobel U (2003) Oral mixed micellar vitamin K for prevention of late vitamin K deficiency bleeding. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 88: F109–F112

Zimmermann H, Desgrandchamps D, Schubiger G (1995) The Swiss Paediatric Surveillance Unit (SPSU). Soz Praventivmed 40: 392–395

Acknowledgements

We thank all participating hospitals of the Swiss Paediatric Surveillance Unit for their contributions and the following physicians for providing detailed information regarding the reported cases: Aarau: G. Zeilinger, V. Jenni; Basel: C. Rudin; Baden: M. Wopmann, G. Staubli; Bern: C. Aebi, G. P. Ramelli, A. Schibler, B. Müller, R. von Vigier, S. Schibli; La Chaux-de-Fonds: A. Corboz; Chur: W. Bär, H. Fricker, J. Schellenberg; Geneva: P. S. Hüppi, S. Sizonenko; Luzern: P. Imahorn, P. Steinmann; Neuchâtel: B. Laubscher, Y. Kernen; St. Gallen: C. Kind, J. Micallef; Winterthur: U. Zimmermann, M. von der Heiden; Zurich: U. Lips, M. Steinlin, O. Bänziger.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schubiger, G., Berger, T.M., Weber, R. et al. Prevention of vitamin K deficiency bleeding with oral mixed micellar phylloquinone: results of a 6-year surveillance in Switzerland. Eur J Pediatr 162, 885–888 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-003-1327-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-003-1327-3