Abstract

The objective was to evaluate the prevalence of chronic conditions (CC) in adolescents in Switzerland; to describe their behaviour (leisure, sexuality, risk taking behaviour) and to compare them to those in adolescents who do not have CC in order to evaluate the impact of those conditions on their well-being. The data were obtained from the Swiss Multicentre Adolescent Survey on Health, targeting a sample of 9268 in-school adolescents aged 15 to 20 years, who answered a self-administered questionnaire. Some 11.4% of girls and 9.6% of boys declared themselves carriers of a CC. Of girls suffering from a CC, 25% (versus 13% of non carriers; P=0.007) and 38% of boys (versus 25%; P=0.002) proclaimed not to wear a seatbelt whilst driving. Of CC girls, 6.3% (versus 2.7%; P=0.000) reported within the last 12 months to have driven whilst drunk. Of the girls, 43% (versus 36%; P=0.004) and 47% (versus 39%; P=0.001) were cigarette smokers. Over 32% of boys (versus 27%; P=0.02) reported having ever used cannabis and 17% of girls (versus 13%; P=0.013) and 43% of boys (versus 36%; P=0.002) admitted drinking alcohol. The burden of their illness had important psychological consequences: 7.7% of girls (versus 3.4%; P=0.000) and 4.9% of boys (versus 2.0%; P=0.000) had attempted suicide during the previous 12 months. Conclusion: experimental behaviours are not rarer in adolescents with a chronic condition and might be explained by a need to test their limits both in terms of consumption and behaviour. Prevention and specific attention from the health caring team is necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The management of chronic conditions (CCs) represents an important part of paediatric practice in Western countries and takes a particular form in adolescence [18, 36]. The health needs of adolescents with a chronic illness or a handicap are indeed linked to the illness they suffer from, to adolescence in general, and to psychosocial problems generated by the interaction between the illness, the adolescent and his immediate environment [41].

The international literature concerning CCs in adolescence highlights the importance of these pathologies to the practitioners, who rarely see these adolescents [11, 18, 21, 28, 43]. However, the prevalence of CCs in adolescence is not well known and varies considerably from one survey to another: most surveys suggest that around 10% of children and adolescents may be affected by a CC [2, 37]. Considerable variations in the definition of CCs and in the survey methods prevent international comparisons [6, 22, 32, 39, 44].

Several authors have suggested that recent progress made in prenatal and paediatric care has helped to improve survival of patients and therefore is responsible for a higher prevalence of CCs in adolescence [2, 3, 37]. This prevalence is important, as CCs have a high economic and social impact due to invalidity, or need for health care facilities which are sometimes highly specialised. This problem has become a priority on a public health level and needs to be carefully evaluated, particularly in Switzerland where few studies have been published.

Despite the highly specialised care available in Western countries, the facilities have not always been adapted to the adolescent's needs, considering that the CC affects the young patient in his global process of development. Adolescents affected by chronic illnesses or handicaps have to deal with the same problems and needs as all other adolescents, in puberty and sexuality development, in school and leisure time, in their relationship with peers, in life styles and risk taking, and in somatic health [41]. The results of some studies have shown that despite the feeling of overprotection and the urge to comply with treatment induced by the illness, adolescents affected by a chronic illness or handicap do not take fewer risks than others. They are as sexually active and are not less exposed than others to the risk of pregnancy or sexually transmitted diseases [2, 4, 7, 30, 42]. Drug and alcohol use or risk taking whilst driving, for example, are as frequent or even more frequent than in others [9, 42]. These young people, because of chronic illnesses or handicaps, might feel the need to assert their conformity by testing the norms [3] and by adopting so called "risk-taking behaviours" [1].

A great number of CCs have consequences on the assessment these adolescents make of their well-being [20, 41]. The difficulties they experience may increase the occurrence of problems such as tiredness, difficulties in socialising, harassment (from others), depression, or suicidal ideations [27, 38, 45].

This article presents the results of a Swiss survey. The objectives were to describe these adolescents, to compare them to adolescents who are not affected by CCs: in their behaviour and lifestyle, and in their well-being (expressed malaise, violence, suicide, need for help).

Subjects and methods

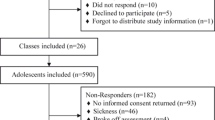

Design of the survey and sample

The data were obtained as part of the Swiss Multicentre Adolescent Survey on Health [19], a detailed description of which is given elsewhere [17]. This national survey was conducted in Switzerland during 1992 and 1993, targeting a representative sample of about 9268 in-school adolescents aged 15 to 20 years. The participants were selected through a one step cluster sampling procedure, stratified by educational background, grade and region. The research protocol was submitted to the Ethics Commission of the Medical Faculty at Lausanne University. A self-administered questionnaire was presented by professionals external to the school in order to ensure optimal confidentiality. It included 80 questions targeting health perception and behaviour, health care utilisation, lifestyles and well-being. The assessment of various health behaviours was limited to the preceding year in order to minimise recall biases.

Definition of the variables (design of the questionnaire)

The participants were asked to answer two questions specifically related to chronic illnesses: (1) "Do you have a physical handicap, that is to say a lesion which affects your body's integrity and limits its functioning in any way?" and (2) "Do you have a chronic illness, that is to say an illness which lasts a long time (at least 6 months) and which may need regular care (e.g. diabetes, scoliosis, etc...)?"

For the purpose of the subsequent analysis, positive answers to both questions were grouped, thus joining the different chronic illnesses and handicaps under a same concept of "Chronic Condition" proposed by Pless and Pinkerton [26] and supported and developed by Ruth Stein [31, 33, 34]. This non-categorised approach allowed us to display the illnesses' consequences, the common needs, and to favour a bio-psycho-social approach, rather than to concentrate on a diagnosis with or without impact on the adolescent's life [34].

Analyses

Using an SPSS-Windows version 10.0 data file, we performed univariate and multivariate analyses to compare the characteristics of the two groups, adolescents with CCs and adolescents without CCs. The χ2 test with a P value <0.05 was used for detecting differences between the two groups.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

The sample was representative of an in-school population of the same age in Switzerland in relation to the different socio-demographic variables [17]. Table 1 shows that adolescents affected by a CC were no different from other adolescents in relation to the socio-demographic variables studied. The matrimonial status alone displayed a higher percentage of divorced parents among boys affected by a CC, although the difference was statistically not significant.

Prevalence

The prevalence of a physical handicap was 4.8% (0.95 confidence interval (CI): 4.2–5.6) among girls and 4.7% (0.95 CI: 4.1–5.3) among boys. The prevalence of a chronic illness was 7.4% (0.95 CI: 6.6–8.2) among girls and 5.8% (0.95 CI: 5.2–6.4) among boys. The prevalence of a CC as defined earlier was slightly higher among girls (11.4%; 0.95 CI: 10.4–12.4) than boys (9.6%; 0.95 CI: 8.8–10.4).

Well-being and need for help

Adolescents suffering from a CC declared themselves as less often in a good mood or well and as more often depressed or desperate (Table 2). Fewer young people with a CC declared themselves satisfied with their personal life (but 75% of them were often satisfied) and they reported making friends less easily than their peers (Table 2). They described themselves as being more worried by their relationship with their friends or parents, and also by the idea of seeing their parents divorced. Moreover, they considered their future less positively than their peers and were less confident of finding a job (Table 2). Fig. 1 shows clearly that more adolescents with a CC, either girls or boys, expressed a need for help, in all the fields explored.

Sexuality

Differences were found only in boys. More boys with a CC reported that they had had a complete sexual relationship. They reported the use of a condom during their latest sexual intercourse more often (Table 3).

Experimental behaviours

Adolescents affected by a CC reported having more experimental behaviours than their peers in relation to seatbelt wearing, or tobacco and alcohol consumption (Table 4). Girls affected by a CC reported to have driven more often under the influence of alcohol, whereas boys affected by a CC reported using cannabis more often than others, during their life as well as during the 30 days preceding the survey. The different variables of experimental behaviours correlated to CCs were included in a logistic regression separately for girls and for boys, confirming that these variables were independently linked to the CC (data not presented).

Violence and suicide

Adolescent girls affected by a CC reported that they were more often victims of sexual aggression (sexual aggression was described as follows: "sexual aggression is when someone in your family, or someone else, touches you in a place you did not want to be touched, or does something to you sexually which they shouldn't have done") and physical violence and more often feared being beaten by their parents (Table 5). Boys as well as girls expressed anger through physical violence more often than their peers.

During the 12 months preceding the survey, adolescents affected by a CC reported suicidal tendencies more frequently and attempting suicide more often. They described the same restraint in talking about it to their friends and family as did their peers and more than 50% of them did not disclose it (Table 6).

Discussion

These analyses, as well as the results of other studies [12, 27, 45], do not show a relationship between CCs and socio-demographic characteristics. The prevalence of CCs in Swiss adolescents is 11.4% among girls and 9.6% among boys. These results are comparable to those found in the international literature, although there are limits to such a comparison as mentioned previously [37, 39, 44]. The prevalence is based on the adolescents' perception of their condition by way of a self-administered questionnaire, thus introducing a declaration bias [45].

The method allowed us to question a representative sample of Swiss adolescents aged 15-20 years attending school or in an apprenticeship (represents circa 80% of the 15-20-year-olds). The participation rate of the survey and the response rate to the questions were high, but our survey did not include the dropouts and those young people working without any training, thus introducing a selection bias. The adolescents with CCs who were unable to follow a normal school, such as those mentally handicapped and severely physically as well as sensory handicapped, were not included. Studies conducted in France and in Switzerland have suggested that it may be more difficult to follow a traditional training pathway when affected by a severe condition [7, 8]. The Swiss survey reported a higher prevalence of CCs among dropouts: 21% (versus 11%) among girls (P<0.005), and 15% (versus 8%) among boys (P<0.005) [8]. The prevalence results are thus underestimated if the general population is considered.

Three main results emerge from this investigation: the magnitude of risk-taking behaviour among the adolescents affected by a CC; the extent of expressed needs, either directly (need for help) or indirectly (problems in social life and mental health); and the great number of victims of violence among the young people affected by a CC.

The high frequency of risk-taking behaviour by adolescents affected by CCs may seem surprising. Some conditions, such as diabetes for example, have been described as having a protective effect on health related behaviour [9, 10, 13]. But most studies have observed a higher frequency of behaviours such as alcohol consumption, driving under the influence of alcohol (among girls), cannabis and tobacco consumption, among adolescents affected by a CC [5, 6, 29, 38, 42]. This active sensation seeking is a part of the personality development and independence inherent to adolescence and may include non-adherence to treatment and lack of compliance with medication. In a more pathological context, associations have been made between sensation-seeking or challenges made to death and depressed moods, anxiety disorders, conflicts with parents, or difficulties in coping with various life events [15].

These assumptions support the use of the concept "experimental behaviours" rather than the use of "risk-taking behaviours", the latter term reflecting the underlying negative aspect of an adult judgement on adolescents [16, 42]. There are also positive aspects to risk-taking: it can express a wish of independence and freedom, a search to test one's limits and to obtain a better knowledge of oneself. This view is particularly important for adolescents affected by a CC, as they have to develop specific adaptative strategies [23, 24].

Sexuality is an important sign of autonomy and maturity acquired during adolescence. Stevens et al. [35] cites a number of studies in which adolescents affected by a CC seemed to have a lower rate of sexual activity than others. They suggested that it is due to a delay in gaining overall social maturity as demonstrated by other studies [14] and to a reserve of their parents to discuss sexuality or puberty with them [35]. On the contrary, it has been observed in the present survey that boys affected by a CC had a higher rate of sexual activity and seemed to protect themselves more often than others. Other studies have noted the same tendencies and also a higher prevalence of pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases among this group, suggesting that in spite of frequent contact with health care professionals, their knowledge and skills about contraception and sexuality are deficient [2, 4, 7, 30, 42].

Experimental behaviours are also influenced by the adolescent's environment but no model has so far been established to report the complexity of this issue [42]. An American survey [5] has underlined the importance of protective factors (familial connectedness, religious values, school network, parental presence) to prevent negative outcomes of experimental behaviours. Other studies have suggested that the higher anxiety levels and the negative body image linked to the chronic illness are responsible for bad perceived well-being, for lower perceived popularity and for lower self-esteem [38, 45]. These perceptions being more highly correlated to intra-familial cohesion than to the CC per se, the authors have proposed that a poor supportive network (family, peer group and friends) plays a role in the adolescent's perception of well-being and in health-compromising behaviour [45]. Moreover, it was observed in a Canadian study that although these adolescents have friends, they have few out-of-school activities and cannot, therefore, entirely share their generation's culture, preventing them from feeling integrated in a group or accepted by their peers [35].

This negative feeling of self-worth could also be related to the high prevalence of violence or of sexual victimisation among the adolescents affected by a CC, as suggested in other studies [40]. Despite the medical follow-up and frequent contacts with health care professionals, the adolescents affected by a CC do not disclose these concerns to their friends or family (more than 50% of them did not discuss it at all) more frequently than other adolescents, and they do not seek mental health services more often [40]. This need for help, which appeared clearly in the Swiss survey in relation to various fields, illustrates the lack of self-confidence these adolescents experience and the lack of support given to them by the people they are in contact with on a regular basis, such as their family, their peers, or the health care professionals.

Conclusion and recommendations

CCs do not prevent experimental behaviours during adolescence; on the contrary they seem to drive these young people to test their own limits, in terms of consumption (alcohol, drugs) as well as in terms of behaviours (sexuality, violence). Moreover, this study shows the high prevalence of depressive moods and suicidal tendency among the adolescents with a CC. Therefore, health promotion and preventive strategies have to be reinforced towards adolescents affected by a CC.

Several preventive strategies could be established: (1) by encouraging intra-familial communication, which is a protective element against risk-taking [25, 45]; (2) by ensuring a global management of the adolescent and her/his CC, by attention to their distress, concerns and questions through an appropriate counselling; (3) by giving her/him the possibility to discuss difficult subjects, and by clinical assessment of the difficulties related to suicide or sexuality and (4) by the screening of the experimental behaviours, and a motivational interview to explain the processes and to show the factors and the dangers, especially the negative outcomes directly linked to their illness, and by counselling and guidance [42]. These strategies can be carried out by the general or specialised practitioners who are in charge of the medical follow-up. They should also associate the skills of a physician trained in adolescent medicine in order to develop a bio-psycho-social approach and prepare these adolescents for adulthood by means of a "transitional care" approach.

Abbreviations

- CC:

-

chronic conditions

- CI:

-

confidence interval

References

Alvin P, Marcelli D (1997) Les maladies chroniques: enjeux physiques et psychiques. In : Michaud PA, Alvin P, Deschamps JP, Frappier JY, Marcelli D, Tursz A (eds) La Santé des adolescents: approches, soins, prévention. Editions Payot, Doin et Université de Montréal, Lausanne, Paris, Montréal, pp 185–207

Bailliere's Clinical Paediatrics International Practice and Research (1994) Current issues in the adolescent patient, chapter 8, p 345

Blum RW (1992) Chronic illness and disability in adolescence. J Adolesc Health 13: 364–368

Blum RW (1997) Sexual health contraceptive needs of adolescents with chronic conditions. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 151: 290–297

Blum RW, Kelly A, Ireland M (2001) Health-risk behaviors and protective factors among adolescents with mobility impairments and learning and emotional disabilities. J Adolesc Health 28: 481–490

Choquet M, Ledoux S (1994) Adolescents. Enquête nationale. Analyse et prospective. INSERM, Paris

Choquet M, Du Pasquier-Fediaevsky L, Manfredi R (1997) Sexual behavior among adolescents reporting chronic conditions: a French national survey. J Adolesc Health 20: 62–67

Delbos Piot I, Narring F, Michaud P-A (1995) La santé des jeunes hors du système de formation: comparaison entre jeunes hors formation et en formation dans le cadre de l'enquête sur la santé et les styles de vie des 15–20 ans en Suisse romande. Santé publique 1: 59–72

Frey MA, Guthrie B, Loveland-Cherry C, Soo Park P, Foster CM (1997) Risky behavior and risk in adolescents with IDDM. J Adolesc Health 20: 38–45

Gold MA, Gladstein J (1993) Substance use among adolescents with diabetes mellitus: preliminary findings. J Adolesc Health 14: 80–84

Gordon Rouse KA, Ingersoll GM, Orr DP (1998) Longitudinal health endangering behavior risk among resilient and nonresilient early adolescents. J Adolesc Health 23: 297–302

Gortmaker SL, Walker DK, Weitzman M, Sobbol AM (1990) Chronic conditions, socio-economic risks, and behavioural problems in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 85: 267–276

Jacobson A, Hauser S, Willett J, Wolfsdorf JI, Dvorak R, Herman L, De Groot M (1997) Psychological adjustment to IDDM: 10-year follow-up of onset cohort of child and adolescent patients. Diabetes Care 20: 811–818

Kokkonen J (1995) The social effects in adult life of chronic physical illness since childhood. Eur J Pediatr 154: 676–681

Le Breton D (1991) Passion du risque. Métaillé, Paris

Michaud P-A, Blum RW, Ferron C (1998) "Bet you I will !" Risk or experimental behaviour during adolescence?. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 152: 224–226

Narring F, Michaud P-A (1995) Methodological issues in adolescent health surveys: the case of the Swiss multicenter-adolescent survey on health. Soz Preventivmed 40: 172–182

Narring F, Michaud P-A (2000) Les adolescents et les soins ambulatoires: résultats d'une enquête nationale auprès des jeunes de 15–20 ans en Suisse. Arch Pediatr 7: 25–33

Narring F, Tschumper A-M, Michaud P-A, Vanetta F, Meyer R, Wydler H (1994) La santé des adolescents en Suisse: rapport d'une enquête nationale sur la santé et les styles de vie des 15–20 ans. Cahiers de recherches Doc IUMSP No 113a 107p, Institut de Médecine Sociale et Préventive, Lausanne

Neinstein LS, Zeltzer LK (1996) Chronic illness in the adolescent. In: Neinstein LS (ed) Adolescent health care, a practical guide. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, pp 1173–1198

Newacheck PW, Halfon N (1998) Prevalence and impact of disabling chronic conditions in childhood. Am J Public Health 88: 610–617

Newacheck PW, Taylor WR (1992) Childhood chronic illness: prevalence, severity and impact. Am J Public Health 82: 364–371

Patterson J (1991) Family resilience to the challenge of child's disability. Pediatr Ann 20: 491–499

Patterson J, Blum RW (1994) La maladie chronique et le handicap chez les jeunes: risques et adaptation. Med Hyg 52: 1406–1409

Patterson J, Blum RW (1996) Risk and resilience among children and youths with disabilities. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 150: 692–698

Pless IB, Pinkerton P (1975) Chronic childhood disorder: promoting patterns of adjustment. Year Book Medical Publishers, Chicago

Pless IB, Cripps HA, Davies JMC, Wadsworth MEJ (1989) Chronic physical illness in childhood: psychological and social effects in adolescence and adult life. Dev Med Child Neurol 31: 746–755

Resnick M, Hutton L (1987) Resiliency among physically disabled adolescents. Psychiatr Ann 17: 796–799

Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, Tabor J, Beuhring T, Sieving RE, Shew M, Ireland M, Bearinger LH, Udry JR (1997) Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA 278: 823–832

Sawyer S, Tully M-A, Colin A (2001) Reproductive and sexual health in males with cystic fibrosis: a case for health professional education and training. J Adolesc Health 28: 36–40

Stein REK, Jessop DJ (1982) A noncategorical approach to chronic childhood illness. Public Health Reports 97: 354–356

Stein REK, Silver EJ (1999) Operationalizing a conceptually based noncategorical definition :a first look at US children with chronic conditions. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 153: 68–74

Stein REK, Bauman LJ, Westbrook LE, Coupey SM, Ireys HT (1993) Framework for identifying children who have chronic conditions: the case for a new definition. J Pediatr 122: 342–347

Stein REK, Westbrook LE, Bauman LJ (1997) The questionnaire for identifying children with chronic conditions: a measure based on a noncategorical approach. Pediatrics 99: 513--521

Stevens SE, Steele CA, Jutal JW, Kalnins IV, Bortolussi JA, Biggar WD (1996) Adolescents with physical disabilities: some psychosocial aspects of health. J Adolesc Health 19: 157–164

Strategies to promote and maintain the healthy development of young people (1992) Summary of the discussions of a UNICEF/WHO working group, 4–6 November 1991, New York. WHO, Geneva, p 29

Surís JC (1995) Global trends of young people with chronic and disabling conditions. J Adolesc Health 17: 17–22

Surís JC (1996) Chronic illness and emotional distress in adolescence. J Adolesc Health 19: 153–156

Surís JC, Blum RW (1993) Disability rates among adolescents: an international comparison. J Adolesc Health 14: 548–552

Surís JC, Resnick MD, Cassuto N, Blum RW (1996) Sexual behaviour of adolescents with chronic disease and disability. J Adolesc Health 19: 124–131

Taddeo D, Frappier JY (1997) Les adolescents porteurs de maladie chronique: accompagnement et guidance. In: Michaud P-A, Alvin P, Deschamps JP, Frappier JY, Marcelli D, Tursz A (eds) La Santé des adolescents: approches, soins, prévention. Editions Payot, Doin et Université de Montréal, Lausanne, Paris, Montréal, pp 208–220

Tursz A, Souteyrand Y, Salmi R (1993) Adolescence et risque. Ed Syros, Paris, p 111

Valencia LS, Cromer BA (2000) Sexual activity and other high-risk behaviors in adolescents with chronic illness: a review. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 13: 53–64

Westbrook LE, Silver EJ, Stein REK (1998) Implications for estimates of disability in children: a comparison of definitional components. Pediatrics 101: 1025--1030

Wolman C, Resnick MD, Harris JL, Blum RW (1994) Emotional well-being among adolescents with and without chronic conditions. J Adolesc Health 15: 199–204

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the Federal Office of Public Health, Switzerland. Grants Nb. 316.91.5139, 316.92.5321, and 316.94.5604.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miauton, L., Narring, F. & Michaud, PA. Chronic illness, life style and emotional health in adolescence: results of a cross-sectional survey on the health of 15-20-year-olds in Switzerland. Eur J Pediatr 162, 682–689 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-003-1179-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-003-1179-x