Abstract

T cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (THRLBCL), originally considered an uncommon variant of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), is recognized by the World Health Organisation as a separate clinicopathological entity since 2008. It predominantly affects middle aged men often presenting with advanced stage disease frequently involving spleen, liver and bone marrow at time of diagnosis. According to the WHO, this lymphoma is morphologically characterized by less than 10% of large neoplastic B cells in a background of abundant T cells and frequently histiocytes. Differentiating THRLBCL from other lymphoproliferative disorders such as Nodular Lymphocyte Predominant Hodgkin Lymphoma (NLPHL) and Lymphocyte-Rich classical Hodgkin lymphoma (LRcHL) is important from a clinical point of view and can be achieved in most cases, given adequate biopsy specimens, by careful morphological and immunohistochemical evaluation of both the neoplastic cells as well as the nonneoplastic stromal component. According to this WHO definition, THRLBCL is still considered a clinically heterogeneous entity, though it is noted that especially the cases containing numerous histiocytes behave aggressively and show resistance to current therapies for DLBCL. Gene expression profiling studies of THRLBCL provided evidence for a prominent role for this histiocytic component that is important for a tolerogenic host immune response in which they may assist neoplastic cells in escaping the T cell-mediated immune surveillance. Therefore, reserving the diagnosis of THRLBCL to cases containing a large proportion of histiocytes might be relevant, as modulating their activity could provide new therapeutic options.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

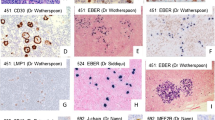

After the description by several groups of a striking infiltrate of reactive T cells in different types of B-cell lymphomas Ramsay et al. introduced in 1988 the term ‘T cell-rich B-cell lymphoma’ (TCRBCL) [1–3]. TCRBCL, occasionally misinterpreted as T cell lymphomas before the era of immunohistochemistry, has been recognized as a caveat for pathologists. A particular subgroup of these TCRBCL may mirror Nodular Lymphocyte Predominant Hodgkin Lymphoma (NLPHL), is characterized by a histiocyte-rich stroma and a poor clinical outcome [4, 5] (Fig. 1). To stress the importance of the histiocytes in these cases, our group introduced in 1992 the term ‘histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma’ (HRBCL) for these TCRBCL in which the background population consisted not only of small reactive T cells but mainly of reactive histiocytes [5].

Morphological and immunohistochemical characterization of THRLBCL (a–e) and NLPHL (f–j). At low magnification, H&E staining illustrates the diffuse (a) versus nodular (b) pattern of lymph node involvement in THRLBCL and NLPHL, respectively. The CD20-positive (c–d) large atypical cells (arrow) of THRLBCL are embedded in stroma-rich in CD68-positive histiocytes (e) and small T lymphocytes in the absence of small B cells. In contrast, in NLPHL (f–j), CD20-positive LP cells (arrow in g) are embedded in nodular aggregates of small B cells (h–i) and surrounded by rosettes of CD3+/CD57+ T cells (asterisk in j)

In the 2001, WHO classification T cell/histiocyte-rich large B cell lymphoma (THRLBCL) was listed as a variant of diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and defined by the ‘presence of scattered large B cells in a background rich in T cells, together with or without histiocytes’ [6]. Within this variant of DLBCL, HRBCL was included. Of interest, clinicopathological studies on THRLBCL according the WHO criteria, thus including cases with a variable number or no histiocytes, resulted in a heterogeneous group of lymphomas with clinical presentation varying from mild to rapidly progressive end-stage disease [7–13].

To improve our diagnostic criteria and concept of HRBCL, a thorough morphologic and immunophenotypic evaluation of 60 cases was performed and the following diagnostic criteria proposed for recognition of an entity we called ‘Histiocyte-rich T cell-rich Large B-cell lymphoma’ [14]: (1) a disturbed lymph node architecture due to a diffuse (or vaguely nodular) neoplastic infiltrate; (2) composed of scattered large atypical neoplastic B cells lacking the expression of CD15; representing only a minority of the overall cell population and occurring as solitary cells (or in very small clusters); and (3) a reactive background infiltrate composed of nonepithelioid histiocytes surrounding the neoplastic cells, small T cells not forming rosettes, and near absent small B cells in the neoplastic areas.

This lymphoma was finally considered as a separate clinicopathological entity in the World Health Organization (WHO) 2008 classification on lymphoid tumors. Based on a consensus expert panel, the 2001 definition on THRLBCL was adapted to cover the lymphoma we described as ‘Histiocyte-rich T cell-rich Large B-cell lymphoma’, and the entity THRLBCL was characterized by ‘a limited number of scattered, large, atypical B cells embedded in a background of abundant T cells and frequently histiocytes’ [15]. Still, the presence of numerous histiocytes was not considered a prerequisite for the diagnosis leaving the entity diagnosed as such too heterogeneous to our opinion.

In this review, we will focus on the pitfalls of diagnosing this rare entity, provide molecular genetic evidence that supports our suggestion to reserve the diagnosis THRLBCL only for cases with a prominent histiocytic background and provide some hope for new therapeutic approaches by mediating their function.

Morphological and immunohistochemical features of THRLBCL

Morphologically, most cases of THRLBCL show a complete disruption of the normal nodal architecture. However, vague nodularity may be present. Scattered large atypical neoplastic B cells are surrounded by a prominent inflammatory background. The neoplastic B cells do not form aggregates or sheets but can vary in size and morphology and can resemble immunoblasts, Hodgkin/Reed–Sternberg-like (HRS) cells or Lymphocyte Predominant-like (LP) cells, typical of DLBCL, classical Hodgkin lymphoma, or NLPHL, respectively [12, 16]. They are embedded within clusters of bland-looking histiocytes and T cells, but T lymphocyte rosetting is typically absent.

Immunohistochemical analysis shows that the neoplastic B cells of THRLBCL mark positive for CD45, CD20 and CD79a, but lack the expression of CD5, CD15 and CD138. Only in rare cases do they express CD30. Tumor cells are typically immunopositive for Bcl6 suggesting their derivation from germinal center B cells although they are mostly CD10-negative. Bcl2 expression, a negative predictive factor in DLBCL, was shown to be positive in up to 50% of THRLBCL. Expression of other histochemical markers such as epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) is variable. The tumoral microenvironment is histochemically characterized by CD68+ histiocytes and lymphocytes with a CD3+/CD5+ profile, which may be CD4+ but most often TIA1+/CD8+ [12, 14, 17, 18].

Differential diagnosis

Even with careful examination of both the neoplastic cells as well as the nonneoplastic cells using immunohistochemistry, differentiating THRLBCL from other hematologic tumors may often remain difficult. The morphologic and immunohistochemical features distinguishing THRLBCL from NLPHL and classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma (cHL) are discussed below and summarized in Table 1.

-

a.

THRLBCL versus NLPHL

Indeed, the distinction between THRLBCL and Nodular Lymphocyte Predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL also known as ‘paragranuloma’) may be difficult. Nevertheless, an important difference between both lymphomas lies in their clinical presentation and prognosis. Therefore, it is crucial to distinguish both entities as NLPHL is an indolent disorder with a favorable prognosis and does not require aggressive treatment in stark contrast to THRLBCL, especially the variant containing many histiocytes [14, 19]. At low magnification, the distinction may not be easy because although THRLBCL most often has a diffuse appearance, it might present with a nodular pattern in a large proportion of cases. Similarities in morphology and immunophenotype of the neoplastic cells further complicate the differential diagnosis. Indeed, the LP (Lymphocyte Predominant) cells or ‘popcorn’ cells of NLPHL and the scattered neoplastic cells of THRLBCL share many characteristics including the expression of pan-B cell markers while lacking the classic HL markers CD15 and CD30 (see Table 1) (adapted from Ref. [20]). In both THRLBCL and NLPHL, neoplastic cells display features of germinal center cells.

However, although NLPHL and THRLBCL are related in as far as their cell of origin is concerned, these lymphomas apparently differ in the host immune response they elicit and differential diagnosis on a pathological basis largely relies on characteristics of the nonneoplastic environment [21, 22]. In THRLBCL, the background stroma is composed of CD8+/TIA1+ small T cells and large numbers of nonepitheloid histiocytes surrounding the neoplastic cells, while small B cells are rare in the neoplastic areas. On the contrary, NLPHL affects the B follicle, and its stroma is composed mainly of small B lymphocytes, with CD4+/CD57+ T cells rosetting around the LP cells. Applying a follicular dendritic cell (FDC) marker, like CD21 or CD23, is helpful as FDC meshworks are partially preserved in the nodular areas containing the small bystander B cells in NLPHL. In contrast, in THRBCL typically affecting the extrafollicular compartment, these follicle mantles and FDC networks are lacking. Alternatively, to FDC stainings, IgD staining can be used to show the presence of residual IgD+ follicle mantles that favor NLPHL [23] above THRBCL. In THRLBCL, large IDO expressing dendritic cells are located in the vicinity of tumor cells and this is not observed in NLPHL. Nearly all stromal components, but not the neoplastic cells, in THRLBCL express STAT1, while in NLPHL STAT1 expression is confined to large dendritic cells adjacent to the T-cell rosettes and some weak expression is discerned in the popcorn cells [23].

Fan et al. described four different immunoarchitectural patterns in NLPHL, with the nodular B cell-rich form (pattern A) being the most frequent and classical form, which should be easy to distinguish from THRLBCL [24]. However, the differential diagnosis becomes more challenging when the number of T cells increases (T cell-rich nodular areas or pattern D) or when the LP cells are predominantly localized outside the B cell-rich nodules (THRLBCL-like areas or patterns C/E). From a purely morphological perspective, distinguishing NLPHL/pattern E from THRBCL is virtually impossible, especially in small biopsy specimens. It is the clinical setting of an advanced clinical stage at time of diagnosis and poor response to treatment that can suggest the diagnosis of THRBCL, while a limited stage and favorable response to treatment would favor the diagnosis of diffuse NLPHL. Since transition was suggested of a NLPHL pattern to a T cell/histiocyte-richlike or diffuse pattern [25], this was not related to a bad prognosis [26, 27]. Finally, increase in the number of atypical cells resembling the image of DLBCL does occur in both NLPHL and THRLBCL only heralding a worse prognosis in the latter [14].

-

b.

THRLBCL versus LRcHL

At low power examination, lymphocyte-rich classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma (LRcHL) can mimic THRLBCL as both entities are characterized by scarce neoplastic cells embedded in a nonneoplastic inflammatory stroma. Without additional immunohistochemical stainings, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish the large atypical cells in THRLBCL from Hodgkin/Reed–Sternberg cells typical for cHL. While the large atypical cells of THRLBCL express CD20, they lack expression of CD15 and CD30. Based on their opposite immunohistochemical profile, the combined use of CD20 and CD15 is helpful to differentiate THRLBCL from LRcHL. Apart from differences in the neoplastic cells, careful study of the nonneoplastic background reveals differences in the composition of the nonneoplastic cells, which in LRcHL typically is composed of abundant small T cells that do form rosettes around the neoplastic cells in the absence of histiocytes [28].

Does THRLBCL occur in childhood?

However, the disease entity THRLBCL preferentially affects middle aged men, a handful of reports were made about TCRBCL (not necessarily THRLBCL) in the pediatric population where it tends to be a local disease [29, 30]. They report a striking predominance of the male gender and unique morphological characteristics of the atypical B cells (large lobulated nucleus with pale chromatin resembling LP cells) as well as absence of EBV infection. In contrast to the reports on THRLBCL in adults, only few pediatric patients presented with advanced stages, and bone marrow involvement by TCRBCL in children was never reported. The little available information on therapy and follow-up showed that the prognosis was favorable after a short intensive polychemotherapy regimen for aggressive lymphomas [30]. In our experience, THRLBCL is extremely rare, if even existing, in a pediatric population and other conditions should be ruled out first, in particular, congenital or acquired immunodeficiencies causing an aberrant immune respons or Hodgkin lymphoma.

Is THRLBCL related to EBV?

Although the association between EBV and THRBCL has not been extensively studied, EBV positivity is not a typical feature of THRLBCL and only a small portion of reported cases display in situ findings of latent EBV infection (e.g., EBER or LMP1 positivity), mostly in cases that show a morphologic resemblance to cHL [31]. Nevertheless, the consensus chapter on THRLBCL in the 2008 WHO classification advises to consider these cases within the spectrum of aggressive EBV-positive DLBCL and avoid classifying them as THRLBCL. One may wonder if some of these cases represent a type of “grey zone lymphoma” with features intermediate between cHL and THRLBCL and correspond to HL cases reported in the older literature that were associated with a poorer prognosis that showed expression of CD20 but not CD15 [32].

Molecular genetics of THRLBCL

The molecular genetic background of THRLBCL is hardly explored as the number of atypical B cells is very low. In single cell analyses of the atypical cells in THRLBCL, monoclonal immunoglobulin rearrangements have been demonstrated [33]. However, conventional PCR technique on whole tissue sections to detect clonality is limited by the number of neoplastic cells.

Cytogenetic analysis was successful in a limited number of cases only but no recurrent abnormalities have been identified yet [21, 34–36]. Comparative genomic hybridization performed on microdissected tumor cells demonstrated that chromosomal imbalances are more numerous in NLPHL as compared to those found in THRLBCL [36]. This finding strongly argues against the hypothesis that THRLBCL develops from NLPHL as tumor progression cannot coincide with a decreased number of chromosomal abnormalities. However, the atypical B cells in both lymphomas were found to share rare imbalances on chromosomes 4q and 19p suggesting a similar precursor for both disorders.

The difficulty of performing molecular genetic studies or microarray gene expression profiling in THRLBCL is that the signature of the neoplastic cells will be outnumbered by the signature of the predominant stromal reaction. Isolation of single tumor cells from the nonneoplastic background is required if one wants to investigate the gene expression profile of the neoplastic cell component but these data are largely lacking at present.

Interestingly, as gene expression profiling of several lymphoma types has shown, the profile of lymphomas is not only defined by the characteristics of the neoplastic cells but also of the stromal component or host immune response that plays a role in predicting the prognosis [37, 38]. To investigate whether the microenvironment surrounding the neoplastic cells of THRBCL could play an important role in determining the clinical outcome in THRLBCL, we investigated the functional meaning and the biological significance of this distinctive stroma by comparing the gene expression profile of whole tissue sections from THRLBCL cases (with prominent histiocytic component) with that of NLPHL [23]. Our GEP profiles of THRLBCL indicate a macrophage/histiocyte-activated status by which the tumor cells acquire several mechanisms to escape T cell-mediated immune surveillance by suppressing the proliferation and activation of effector T cells and their conversion to regulatory T cells. Similar to the data from Chetaille et al., the molecular signature we found in THRLBCL was dominated by an interferon-dependent pathway including STAT-1 [39]. Both IFN-γ as well as proteins that are upregulated in macrophages upon treatment with IFN-γ, including indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and Chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 8 (CCL8), are upregulated in THRLBCL. CCL8, one of the most potent monocyte chemoattractants, may contribute to the histiocyte-rich composition of the stroma in THRLBCL while IFN-γ is responsible for the activation of histiocytes and, in synergy with Toll-like receptor ligands, for the production of high levels of IDO by histiocytes and dendritic cells. IDO, which might be expressed by tumor cells as well, has been described to promote tumoral immune tolerance in a variety of hematopoietic malignancies [40, 41]. IDO degrades tryptophan thus lowering tryptophan concentration in the local microenvironment. Such altered microenvironment protects tumor cells from rejection by the immune system as T lymphocytes are very sensitive to tryptophan shortage. IDO thus suppresses local T cell responses and alters the conversion of effector T cells into T regulatory cells. Our findings may explain the peculiar composition of the stroma in THRLBCL as well as the bad prognosis of these patients.

Of interest, other genes found to be upregulated in THRLBCL overlapped significantly with genes found to be related to an unfavorable immune response in a subset of follicular lymphomas and genes found to be related to host inflammatory response in DLBCL [37, 38]. Our data are also in concordance with the GEP study by Monti et al. that recognized a particular subtype of DLBCL, which they indicated as DLBCL with “host inflammatory response” [42]. Cases of this subtype showed several characteristics reminiscent of THRLBCL, not only by their morphology but also by their clinical presentation and outcome.

On the contrary, the molecular signature in NLPHL identified B-cell characteristics, implying that the follicular component seen in typical NLPHL is the predominant feature. Since there was minimal overlap with the signature from the purified lymphocyte-predominant cells as reported by Brune et al., [43] we concluded that the profile was determined by the abundant background B cells and not by the scarce neoplastic cells.

Treatment

Multiple study groups compared the clinical outcome between DLBCL and THRLBCL. Some retrospective studies showed comparable outcome, while others report that THRLBCL, especially using a more restricted diagnosis (rich in histiocytes), has a worse prognosis and may, therefore, need more aggressive therapy [7, 14, 44, 45]. This dichotomy results in uncertainty about the best therapeutic approach when the diagnosis of THRLBCL is made. Nevertheless, new insights in the molecular pathogenesis of this disease will provide clues for targeted therapy with newly developed drugs adapted to the specific characteristics of the neoplastic cells or its stromal component. Mediating the host stromal response that is hallmarked by an increased expression of IFN-γ, CCL8, IDO and VSIG4, could, e.g., be done through inhibition of IDO [46].

Conclusion and perspectives

T cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma (THRLBCL) is a relatively new entity. Morphologically differentiating THRLBCL from Nodular Lymphocyte Predominant Hodgkin Lymphoma (NLPHL) is not always easy. Since these entities have a different prognosis and require a different therapeutic approach, an initial correct histopathological diagnosis is of the utmost importance. The clue to a correct differential diagnosis lies in the careful morphologic and immunohistochemical examination of the tumor microenvironment, which defines the major difference between the two entities.

GEP studies stress the significant role of the microenvironment in THRLBCL and emphasize the crucial role of its histiocytes supporting their presence as a diagnostic hallmark in the identification of this particular lymphoma. Because of these results, we suggest to diagnose lymphoma cases as THRLBCL only if the nonneoplastic component is rich in histiocytes. However, in addition to further studies on the biological significance of the peculiar stroma characterizing THRLBCL, molecular and cytogenetic studies of isolated tumor cells are necessary to provide more insights in the pathogenesis and the more precise delineation of THRLBCL from other lymphomas.

References

Jaffe E et al (1984) Diffuse B cell lymphoma with T cell predominance in patients with follicular lymphoma or ‘pseudo T cell lymphoma’. Lab Investig 50:27A–28A

Mirchandani I et al (1985) B-cell lymphomas morphologically resembling Tcell lymphomas. Cancer 56:1578–1583

Ramsay AD, Smith WJ, Isaacson PG (1988) T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol 12(6):433–443

Chittal SM et al (1991) Large B-cell lymphoma rich in T-cells and simulating Hodgkin’s disease. Histopathology 19(3):211–220

Delabie J et al (1992) Histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma. A distinct clinicopathologic entity possibly related to lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin’s disease, paragranuloma subtype. Am J Surg Pathol 16(1):37–48

Gatter KC, Warnke R (2001) Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. In: Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman J (eds) World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. IARC Press, Lyon, pp 171–4

Bouabdallah R et al (2003) T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphomas and classical diffuse large B-cell lymphomas have similar outcome after chemotherapy: a matched-control analysis. J Clin Oncol 21(7):1271–1277

De Wolf-Peeters C, Pittaluga S (1995) T-cell rich B-cell lymphoma: a morphological variant of a variety of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas or a clinicopathological entity? Histopathology 26(4):383–385

Greer JP et al (1995) T-cell-rich B-cell lymphomas: diagnosis and response to therapy of 44 patients. J Clin Oncol 13(7):1742–1750

Harris NL (1999) Hodgkin’s lymphomas: classification, diagnosis, and grading. Semin Hematol 36(3):220–232

Krishnan J, Wallberg K, Frizzera G (1994) T-cell-rich large B-cell lymphoma. A study of 30 cases, supporting its histologic heterogeneity and lack of clinical distinctiveness. Am J Surg Pathol 18(5):455–465

Lim MS et al (2002) T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma: a heterogeneous entity with derivation from germinal center B cells. Am J Surg Pathol 26(11):1458–1466

Rodriguez J, Pugh WC, Cabanillas F (1993) T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma. Blood 82(5):1586–1589

Achten R et al (2002) T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. J Clin Oncol 20(5):1269–1277

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H et al (2008) WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, 4th edn. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon

Dogan A et al (2003) Micronodular T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma of the spleen: histology, immunophenotype, and differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol 27(7):903–911

Fraga M et al (2002) T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma is a disseminated aggressive neoplasm: differential diagnosis from Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Histopathology 41(3):216–229

Gascoyne RD et al (1997) Prognostic significance of Bcl-2 protein expression and Bcl-2 gene rearrangement in diffuse aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Blood 90(1):244–251

Diehl V et al (1999) Clinical presentation, course, and prognostic factors in lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin’s disease and lymphocyte-rich classical Hodgkin’s disease: report from the European Task Force on Lymphoma Project on Lymphocyte-Predominant Hodgkin’s Disease. J Clin Oncol 17(3):776–783

Abramson JS (2006) T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma: biology, diagnosis, and management. Oncologist 11(4):384–392

Brauninger A et al (1999) Molecular analysis of single B cells from T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma shows the derivation of the tumor cells from mutating germinal center B cells and exemplifies means by which immunoglobulin genes are modified in germinal center B cells. Blood 93(8):2679–2687

Marafioti T et al (1997) Origin of nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin’s disease from a clonal expansion of highly mutated germinal-center B cells. N Engl J Med 337(7):453–458

Van Loo P et al (2009) T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma shows transcriptional features suggestive of a tolerogenic host immune response. Haematologica 95(3):440–448

Fan Z et al (2003) Characterization of variant patterns of nodular lymphocyte predominant hodgkin lymphoma with immunohistologic and clinical correlation. Am J Surg Pathol 27(10):1346–1356

Hansmann ML et al (1989) Nodular paragranuloma can transform into high-grade malignant lymphoma of B type. Hum Pathol 20(12):1169–1175

Boudova L et al (2003) Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma with nodules resembling T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma: differential diagnosis between nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma and T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma. Blood 102(10):3753–3758

Torlakovic E et al (2001) The transcription factor PU.1, necessary for B-cell development is expressed in lymphocyte predominance, but not classical Hodgkin’s disease. Am J Pathol 159(5):1807–1814

Sanders ME et al (1988) Molecular pathways of adhesion in spontaneous rosetting of T-lymphocytes to the Hodgkin’s cell line L428. Cancer Res 48(1):37–40

Lones MA, Cairo MS, Perkins SL (2000) T-cell-rich large B-cell lymphoma in children and adolescents: a clinicopathologic report of six cases from the Children’s Cancer Group Study CCG-5961. Cancer 88(10):2378–2386

Tiemann M et al (2005) Proliferation rate and outcome in children with T-cell rich B-cell lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study from the NHL-BFM-study group. Leuk Lymphoma 46(9):1295–1300

Axdorph U et al (2002) T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma—diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. APMIS 110(5):379–390

Jaffe E, Muller-Hermelink H (1999) Relationship between Hodgkin’s disease and nonHodgkin’s lymphomas. In: Mauch P, Armitage J, Diehl V et al (eds) Hodgkin’s disease. Lippincott Raven, Philadelphia, pp 181–194

Osborne BM, Butler JJ, Pugh WC (1990) The value of immunophenotyping on paraffin sections in the identification of T-cell rich B-cell large-cell lymphomas: lineage confirmed by JH rearrangement. Am J Surg Pathol 14(10):933–938

Achten R et al (2002) Histiocyte-rich, T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma: a distinct diffuse large B-cell lymphoma subtype showing characteristic morphologic and immunophenotypic features. Histopathology 40(1):31–45

Braeuninger A et al (1997) Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells in lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin disease represent clonal populations of germinal center-derived tumor B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94(17):9337–9342

Franke S et al (2001) Lymphocyte predominance Hodgkin disease is characterized by recurrent genomic imbalances. Blood 97(6):1845–1853

Dave SS et al (2004) Prediction of survival in follicular lymphoma based on molecular features of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. N Engl J Med 351(21):2159–2169

Lenz G et al (2008) Stromal gene signatures in large-B-cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med 359(22):2313–2323

Chetaille B et al (2009) Molecular profiling of classical Hodgkin lymphoma tissues uncovers variations in the tumor microenvironment and correlations with EBV infection and outcome. Blood 113(12):2765–3775

Curti A et al (2009) The role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in the induction of immune tolerance: focus on hematology. Blood 113(11):2394–2401

Ninomiya S et al (2011) Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in tumor tissue indicates prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Ann Hematol 90(4):409–416

Monti S et al (2005) Molecular profiling of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identifies robust subtypes including one characterized by host inflammatory response. Blood 105(5):1851–1861

Brune V et al (2008) Origin and pathogenesis of nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma as revealed by global gene expression analysis. J Exp Med 205(10):2251–2268

El Weshi A (2007) T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma: clinical presentation, management and prognostic factors: report on 61 patients and review of literature. Leuk Lymphoma 48(9):1764–1773

Aki H et al (2004) T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of 21 cases and comparison with 43 cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Res 28(3):229–236

Lob S et al (2009) Inhibitors of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase for cancer therapy: can we see the wood for the trees? Nat Rev Cancer 9(6):445–452

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tousseyn, T., De Wolf-Peeters, C. T cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma: an update on its biology and classification. Virchows Arch 459, 557–563 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-011-1165-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-011-1165-z