Abstract

The autopsy has long been regarded as an important tool for clinical confrontation, education and quality assurance. The aims of this study were to examine the correlation between the clinical diagnosis and autopsy findings in adult patients who died in an intensive care unit (ICU) and to identify the types of errors in diagnosis to improve quality of care. Autopsies from 289 patients who died in the ICU during a 2-year period were studied. Post-mortem examination revealed unexpected findings in 61 patients (21%) including malignancy, pulmonary embolism, aspergillosis, myocardial or mesenteric infarction and unsuspected bacterial, viral or fungal infection. These unexpected findings were classified as Goldman class I errors in 17 (6%), class II in 38 (13%) and class III in six (2%) cases. Although the incidence of unexpected findings with clinical significance was low, post-mortem examination remains a valuable source of pertinent information that may improve the management of ICU patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

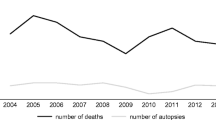

During the past 30 years, autopsy rates have decreased worldwide [2, 40, 49] partly because of the availability of new and more effective technologies for diagnostic procedures, particularly in terms of imaging techniques. Other reasons have also been suggested, including reluctance to ask relatives for their consent and fear of medico-legal implications [23, 30]. Pathologists themselves have sometimes become reluctant to perform autopsies because of the possible infectious risks and the lack of evidence of the usefulness of the autopsy examination [20, 27, 30]. Delays in the communication of autopsy results by pathologists may also contribute to the reduced autopsy rates [32, 33, 42].

However, studies on autopsies have demonstrated their usefulness not only in determining the exact cause of death but also in visualising how a patient responded to treatment. The autopsy is often considered a fundamental element of quality control in medicine, being the ultimate audit of clinical practice [26, 28, 51]. The persisting discordance between clinical and autopsy diagnoses is also an argument for continuing to perform autopsies [9, 17, 34, 36]. Studies carried out during the past 20 years have failed to show a significant increase in diagnostic agreement between ante- and post-mortem diagnoses; this persistent discord is observed in all groups of patients (neonatal, paediatric, elderly and psychiatric patients) and in all hospitals, whether affiliated to a university or not [7, 14, 15, 22, 24–26, 44, 50, 52, 53]. The autopsy also provides an excellent basis for teaching students the fundamentals of anatomy and the manifestations of disease. It provides important information on the effects of newer drugs on normal and on diseased tissues [3, 37, 47] and is a valuable tool for detecting and evaluating emerging diseases [28, 29].

Published discrepancy rates between ante- and post-mortem diagnoses vary between 10 and 50% depending on the criteria for post-mortem examination, the completeness of the post-mortem examination, the methods used to evaluate the differences and the population studied [7, 8, 26, 34, 41, 43, 45, 53]. Despite all the supportive measures available for the treatment of critically ill patients, the difficulty in obtaining an adequate medical history from these patients and the speed at which their critical condition develops can prevent the ICU physician from making a diagnosis that, if established, would probably prevent the death of these patients [19]. The objective of the present study was to compare pre- and post-mortem diagnostic findings and to determine the types of errors in an ICU-patient population to improve quality control of future care.

Patients and methods

We reviewed the clinical and post-mortem findings of all patients who died in the Department of Intensive Care of Erasme University Hospital between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2005 and who underwent post-mortem examination. This department includes five medico-surgical ICUs with 3,000 admissions a year and a 13% mortality rate. Complete body autopsies were performed within 48 h of death, and the procedure included macroscopic and microscopic assessment of all internal organs and the brain when indicated (neurological alterations or specific concerns regarding central nervous system pathology). As recommended by the Association of Directors of Anatomic and Surgical Pathology [1], post-mortem examinations were performed after a written Quality Control and Quality Assurance plan for our Department of Pathology. Data obtained from the charts included age, sex, length of ICU and hospital stay and major clinical findings, including the presumed cause of death and underlying diseases. Autopsy diagnoses included histological and immunohistochemical findings as listed in the final autopsy reports. To avoid subjectivity in the interpretation of histological findings, a second staff pathologist had been consulted in doubtful cases.

The comparisons between ante- and post-mortem diagnoses were classified as major and minor discrepancies or as a complete agreement according to the classification proposed by Goldman et al. [17]. According to this classification, a class I discrepancy is a missed major diagnosis that would have changed patient management and might have resulted in cure or prolonged survival. A class II discrepancy includes a missed major diagnosis that would not have modified ongoing patient care. A class III discrepancy refers to a missed minor diagnosis associated with the terminal disease but not directly responsible for death, and a class IV discrepancy refers to other missed minor diagnoses. In Goldman class V, there is a complete agreement between clinical and post-mortem diagnoses. In case of multiple unexpected findings, only the most severe level of discrepancy was considered.

Statistical analysis included a chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test to compare categorical variables and a Student’s t test to compare mean values. A p value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Study population

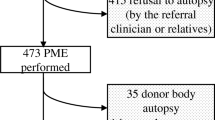

Of the total of 786 patients who died in the 2-year period, 289 (37%) had a post-mortem examination. Refusal of the family was the most frequent reason for not performing an autopsy. For the autopsy cases, the male to female ratio was 1.5, and the median age was 71 years (range, 19–95 years). Of the autopsy population, 19.5% had been admitted to the ICU immediately after surgery. Among the non-surgical patients, the main reason for admission was neurological problems.

The characteristics of these patients are presented in Table 1.

Comparison of clinical and post-mortem diagnoses

Post-mortem examinations revealed unexpected findings in 61 (21%) patients, which were class I in 17 (6%), class II in 38 (13%) and class III in six (2%) patients. The major discrepancies (class I and II) are presented in Table 2 and included fungal, bacterial and viral infection, pulmonary embolism, mesenteric infarction, acute pancreatitis, major haemorrhage and myocardial infarction. Minor findings included non-metastatic malignancy, kidney infarction and lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

Major discrepancies were detected more frequently in the 68 (23.5%) patients staying more than 10 days than in those staying fewer than 10 days in the ICU (31% vs 15%, p = 0.008; Table 3). No statistical difference was observed with regard to sex or age.

Discussion

Our autopsy rate of 37% is greater than the minimal rate of 25% considered adequate [54] and close to the 35% considered as ideal [55]. Post-mortem examination revealed unexpected findings in 21% of our patients, with important diagnoses like malignancy, various types of infection, myocardial or mesenteric infarctions and pulmonary embolism. These unexpected findings were considered as class I in 6% and as class II in 13% of the cases. These results are comparable with our previous study [13] where the discrepancy rate was 23%. Other studies have reported major diagnostic discrepancies in 5–40% of all hospitalised patients and in 7–32% of ICU patients [7, 10, 11, 15, 31, 43, 46, 48, 50]. These differences among studies may be explained not only by different ICU populations but also by differences in the indications for autopsy. Studies from hospitals in which autopsies are predominantly performed in complicated cases may be expected to show higher discrepancy rates [39]. On the other hand, Ong et al. [38] reported a rate as low as 3% for missed major (class I) diagnoses in a study that included only trauma- and burn-related deaths in the ICU.

Several autopsy studies have reported that infections, particularly fungal infections, are the most common discrepant finding [34, 35, 43, 45, 46]. The methods available to diagnose fungal infections in patients do not reliably differentiate colonization from systemic infection, and blood cultures (indicating invasive infection) are negative in 50% of patients with invasive candidiasis [16]. The often rapid fatal outcome after ICU admission suggests that colonization with fungi can occur before ICU admission [12].

In our present series, unexpected fungal infections were identified in only nine patients. Infections were the most frequently missed major diagnoses in the study by Nadrous et al. [35], with a total of 26 missed infections, of which 13 were fungal. Of these fungal infections, three were categorised as type I discrepancies. Silfvast et al. [46] reported that five of the eight class I discrepancies in their analysis of 346 autopsy reports on ICU patients were infections that occurred in patients already being treated for another infection, highlighting the difficulties in diagnosing infections in ICU patients. Previous studies have suggested that transplant recipients may be more prone to missed infections [34, 50]. Mort and Yeston [34] found that 85% of missed diagnoses in a surgical population had an infectious aetiology. Although it may be argued that terminal infections, especially disseminated aspergillosis, would not have been treated more effectively by earlier diagnosis, as new therapies emerge [21], it remains important to recognise atypical presentations of infection, especially in immunocompromised patients. In the present series, 19 of 55 major discrepancies (class I and class II) were of an infectious origin. With regard to the post-surgical patients, three of nine major discrepancies were infections; in these three cases, invasive aspergillosis was detected, and in one of the three patients, immunohistochemistry revealed the presence of cytomegalovirus in lung and colon tissues and of herpes simplex virus in the oesophagus. This patient, however, was immunocompromised with a known non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Early autopsy studies (before 1970) reported clinically undiagnosed malignancies in 18–35% of patients [5]. Since then, newer diagnostic techniques and improved clinical acumen gained from previous autopsy studies have contributed to a decline in the rate of detection of undiagnosed neoplastic diseases to as low as 4% in a series by Goldman et al. [18]. In the present series, 12 cases of malignancy were identified as major discrepancies. Likewise, we detected four cases of clinically undiagnosed pulmonary embolism, emphasising the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for theses diagnoses in the critically ill [6, 7, 50].

Myocardial infarction is also a commonly missed major diagnosis. Perkins et al. [39] found that only 55% of patients undergoing a post-mortem examination had an electrocardiogram performed at any stage during their ICU stay. These authors suggested that the index of suspicion for ischaemic heart disease is inappropriately low in the critically ill patient. Although an electrocardiogram is performed almost every day in our ICU, post-mortem examination still revealed myocardial infarction as a major discrepancy in eight patients.

We found a higher rate of major discrepancies in patients staying more than 10 days in the ICU. Mort and Yeston [34] reported that patients staying more than 48 h were more likely to have a major discrepancy than those who died within 48 h of ICU admission. Other studies, however, have reported no relation between the length of stay and post-mortem findings [4, 10, 15, 35, 39].

There are several limitations of this study, including that this is a retrospective analysis and that the diagnostic work-up of each individual was not critically reviewed; it is possible that variability in the investigation influenced the incidence of missed diagnoses. The strength of the study is the large number of patients hospitalised in a large medico-surgical department of intensive care. Nevertheless, these findings from an academic hospital may not be applicable to other units.

In conclusion, this study reveals a number of significant discrepancies between clinical diagnoses before death and post-mortem findings, even in a large academic institution. Our observations reinforce the importance of the post-mortem examination in identifying suspected or unexpected diagnoses, even in patients receiving close monitoring and intensive care. The post-mortem examination should not be seen as a means of providing evidence of clinical malpractice but rather as a positive educational tool to improve patient care in an attempt to reduce the number of clinically missed diagnoses; autopsy should be considered in every patient who dies in the ICU.

References

Association of Directors of Anatomic and Surgical Pathology (1991) Recommendations on quality control and quality assurance in anatomic pathology. Am J Surg Pathol 15:1007–1009

Baker PB, Zarbo RJ, Howanitz PJ (1996) Quality assurance of autopsy face sheet reporting, final autopsy report turnaround time, and autopsy rates: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 10,003 autopsies from 418 institutions. Arch Pathol Lab Med 120:1003–1008

Baron JH (2000) Clinical diagnosis and the function of the autopsy. J R Soc Med 93:463–466

Battle RM, Pathak D, Humble CG, Key CR, Vanatta PR, Hill RB, Anderson RE (1987) Factors influencing discrepancies between premortem and postmortem diagnoses. JAMA 258:339–344

Bauer FW, Robbins SL (1972) An autopsy study of cancer patients. I. Accuracy of the clinical diagnoses (1955 to 1965) Boston City Hospital. JAMA 221:1471–1474

Berlot G, Dezzoni R, Viviani M, Silvestri L, Bussani R, Gullo A (1999) Does the length of stay in the intensive care unit influence the diagnostic accuracy? A clinical-pathological study. Eur J Emerg Med 6:227–231

Blosser AS, Zimmerman HE, Stauffer JL (1998) Do autopsies of critically ill patients reveal important findings that were clinically undetected? Crit Care Med 26:1332–1336

Boers M, Nieuwenhuyzen Kruseman AC, Eulderink F, Hermans J, Thompson J (1988) Value of autopsy in internal medicine: a 1-year prospective study of hospital deaths. Eur J Clin Investig 18:314–320

Burton EC, Troxclair DA, Newman WP 3rd (1998) Autopsy diagnoses of malignant neoplasms: how often are clinical diagnoses incorrect? JAMA 280:1245–1248

Combes A, Mokhtari M, Couvelard A, Trouillet JL, Baudot J, Hénin D, Gibert C, Chastre J (2004) Clinical and autopsy diagnoses in the intensive care unit: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med 164:389–392

Dhar V, Perlman M, Vilela MI, Haque KN, Kirpalani H, Cutz E (1998) Autopsy in a neonatal intensive care unit: utilization patterns and associations of clinicopathologic discordances. J Pediatr 132:75–79

Dimopoulos G, Piagnerelli M, Berre J, Eddafali B, Salmon I, Vincent JL (2003) Disseminated aspergillosis in intensive care unit patients: an autopsy study. J Chemother 15:71–75

Dimopoulos G, Piagnerelli M, Berre J, Salmon I, Vincent JL (2004) Post mortem examination in the intensive care unit: still useful? Intensive Care Med 30:2080–2085

Egervary M, Szende B, Roe FJ, Lee PN (2000) Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of lung cancer in Budapest in an institute specializing in chest diseases. Pathol Res Pract 196:761–766

Fernandez-Segoviano P, Lazaro A, Esteban A, Rubio JM, Iruretagoyena JR (1988) Autopsy as quality assurance in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 16:683–685

Geha DJ, Roberts GD (1994) Laboratory detection of fungemia. Clin Lab Med 14:83–97

Goldman L, Sayson R, Robbins S, Cohn LH, Bettmann M, Weisberg M (1983) The value of the autopsy in three medical eras. N Engl J Med 308:1000–1005

Goldman L (1984) Diagnostic advances v the value of the autopsy. 1912–1980. Arch Pathol Lab Med 108:501–505

Gut AL, Ferreira AL, Montenegro MR (1999) Autopsy: quality assurance in the ICU. Intensive Care Med 25:360–363

Haber SL (1996) Whither the autopsy? Arch Pathol Lab Med 120:714–717

Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF, Bennett JE, Greene RE, Oestmann JW, Kern WV, Marr KA, Ribaud P, Lortholary O, Sylvester R, Rubin Rh, Wingard JR, Stak P, Durand C, Caillot D, Thiel E, Chandrasekar PH, Hodges MR, Schlamm HT, Troke PF, De Pauw B, Invasive Fungal Infections Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Global Aspergillus Study Group (2002) Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med 347:408–415

Juvin P, Teissiere F, Brion F, Desmonts JM, Durigon M (2000) Postoperative death and malpractice suits: is autopsy useful? Anesth Analg 91:344–346

Kamal IS, Forsyth DR, Jones JR (1997) Does it matter who requests necropsies? Propective study of clinical audit on rate of requests. BMJ 314:1729

Kumar P, Taxy J, Angst DB, Mangurten HH (1998) Autopsies in children: are they still useful? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 152:558–563

Kumar P, Angst DB, Taxy J, Mangurten HH (2000) Neonatal autopsies: a 10-year experience. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 154:38–42

Landefeld CS, Chren MM, Myers A, Geller R, Robbins S, Goldman L (1988) Diagnostic yield of the autopsy in a university hospital and a community hospital. N Engl J Med 318:1249–1254

Lundberg GD (1996) College of American Pathologists Conference XXIX on restructuring autopsy practice for health care reform: let’s make this autopsy conference matter. Arch Pathol Lab Med 120:736–738

Lundberg GD (1998) Low-tech autopsies in the era of high-tech medicine: continued value for quality assurance and patient safety. JAMA 280:1273–1274

Marche C (1990) The autopsy and AIDS. Evaluation and perspectives. Ann Pathol 10:225–228

Marwick C (1995) Pathologists request autopsy revival. JAMA 273:1889–1891

McPhee SJ, Bottles K (1985) Autopsy: moribund art or vital science? Am J Med 78:107–113

McPhee SJ, Bottles K, Lo B, Saika G, Crommie D (1986) To redeem them from death. Reactions of family members to autopsy. Am J Med 80:665–671

McPhee SJ (1996) Maximizing the benefits of autopsy for clinicians and families. What needs to be done. Arch Pathol Lab Med 120:743–748

Mort TC, Yeston NS (1999) The relationship of pre mortem diagnoses and post mortem findings in a surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 27:299–303

Nadrous HF, Afessa B, Pfeifer A, Peters SG (2003) The role of autopsy in the intensive care unit. Mayo Clin Proc 78:947–950

Nichols L, Aronica P, Babe C (1998) Are autopsies obsolete? Am J Clin Pathol 110:210–218

O’Grady G (2003) Death of the teaching autopsy. BMJ 327:802–803

Ong AW, Cohn SM, Cohn KA, Jaramillo DH, Parbhu R, McKenney MG, Barquist ES, Bell MD (2002) Unexpected findings in trauma patients dying in the intensive care unit: results of 153 consecutive autopsies. J Am Coll Surg 194:401–406

Perkins GD, McAuley DF, Davies S, Gao F (2003) Discrepancies between clinical and postmortem diagnoses in critically ill patients: an observational study. Crit Care 7:R129–R132

Potet F (1996) Autopsy. A method for evaluating the quality of care. Ann Pathol 16:409–413

Rao MG, Rangwala AF (1990) Diagnostic yield from 231 autopsies in a community hospital. Am J Clin Pathol 93:486–490

Roberts WC (1978) The autopsy: its decline and suggestion for its revival. N Engl J Med 299:332–338

Roosen J, Frans E, Wilmer A, Knockaert DC, Bobbaers H (2000) Comparison of premortem clinical diagnoses in critically ill patients and subsequent autopsy findings. Mayo Clin Proc 75:562–567

Salib E, Tadros G, Ambrose A (2000) Autopsy in elderly psychiatric inpatients: a retrospective review of autopsy findings of deceased elderly psychiatric inpatients in north Cheshire 1980–1996. Med Sci Law 40:20–27

Sarode VR, Datta BN, Banerjee AK, Banerjee CK, Joshi K, Bhusnurmath B, Radotra BD (1993) Autopsy findings and clinical diagnoses: a review of 1,000 cases. Human Pathol 24:194–198

Silfvast T, Takkunen O, Kolho E, Andersson LC, Rosenberg P (2003) Characteristics of discrepancies between clinical and autopsy diagnoses in the intensive care unit: a 5-year review. Intensive Care Med 29:321–324

Slavin G, Kirkham N, Underwood JCE, Molt JM, Hopkins A, Jackson BT, Windsor CWO (1991) The autopsy and audit. Report of the Joint Working Party of the Royal College of Pathologists, the Royal College of Physicians of London and the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Royal College of Pathologists, London

Sonderegger-Iseli K, Burger S, Muntwyler J, Salomon F (2000) Diagnostic errors in three medical areas: a necropsy study. Lancet 355:2027–2031

Start RD, Firth JA, Macgillivray F, Cross SS (1995) Have declining clinical necropsy rates reduced the contribution of necropsy to medical research? J Clin Pathol 48:402–404

Tai DY, El-Bilbeisi H, Tewari S, Mascha EJ, Wiedemann HP, Arroliga AC (2001) A study of consecutive autopsies in a medical ICU: a comparison of clinical cause of death and autopsy diagnosis. Chest 119:530–536

The Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia Autopsy Working Party (2004) The decline of the hospital autopsy: a safety and quality issue for healthcare in Australia. Med J Aust 180:281–285

Tse GM, Lee JC (2000) A 12-month review of autopsies performed at a university-affiliated teaching hospital in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 6:190–194

Twigg SJ, McCrirrick A, Sanderson PM (2001) A comparison of post mortem findings with post hoc estimated clinical diagnoses of patients who die in a United Kingdom intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med 27:706–710

Yalamarthi S, Ridley S, Barker T (1998) Agreement between ante-mortem diagnoses, death certificates and post-mortem causes of death in critically ill patients. Clin Intensive Care 9:100–104

Yesner R, Robinson MJ, Goldman L, Reichert CM, Engel L (1985) A symposium on the autopsy. Pathol Annu 20:441–477

Acknowledgement

The authors declare that the experiments comply with the current laws of Belgium.

This work has been carried out with the support of grants awarded by the “Fondation Yvonne Boël” (Brussels, Belgium).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maris, C., Martin, B., Creteur, J. et al. Comparison of clinical and post-mortem findings in intensive care unit patients. Virchows Arch 450, 329–333 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-006-0364-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-006-0364-5