Abstract

Pathological staging and surgical margin status of radical prostatectomy specimens are next to grading the most important prognosticators for recurrence. A central review of pathological stage and surgical margin status was performed on a series of 552 radical prostatectomy specimens of patients, participating in the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer trial 22911. Inclusion criteria of the trial were pathological stage pT3 and/or positive surgical margin at local pathology. All specimens were totally embedded. Data of the central review were compared with those of local pathologists and related to clinical follow-up. Although a high concordance between review pathology and local pathologists existed for seminal vesicle invasion (94%, κ=0.83), agreement was much less for extraprostatic extension (57.5%, κ=0.33) and for surgical margin status (69.4%, κ=0.45). Review pathology of surgical margin status was a stronger predictor of biochemical progression-free survival in univariate analysis [hazard ratio (HR)=2.16 and p=0.0002] than local pathology (HR=1.08 and p>0.1). The review pathology demonstrated a significant difference between those with and without extraprostatic extension (HR=1.83 and p=0.0017), while local pathology failed to do so (HR=1.05 and p>0.8). The observations suggest that review of pathological stage and surgical margin of radical prostatectomy strongly improves their prognostic impact in multiinstitutional studies or trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pathological staging of radical prostatectomy specimens is considered an important tool for the assessment of the prognosis of individual patients and it helps the urologist in decision-making with regard to the installment of adjuvant therapy. Another important role of pathological staging of radical prostatectomy specimens is the definition of a homogeneous patient population to be studied in the context of a clinical study or trial.

To enable an accurate pathological staging, the radical prostatectomy specimens should be processed in a uniform way, allowing the whole specimen to be examined microscopically. Several consensus guidelines on processing and reporting of radical prostatectomy specimens were published recently [9, 14], avoiding confusion and variation among pathologists. Preferentially, the prostatectomy specimens should be totally embedded and the apex and bladder neck should be sectioned in a parasagittal plane for an optimal appreciation of the surgical margins.

The prognostic impact of pathological stage is undisputed; particularly, the invasion of seminal vesicles is considered a highly unfavorable feature. However, as a consequence of widespread prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing, a stage shift in prostatectomy specimens was noted in recent years [5, 17] and the prognostic significance of pathological stage in current patient populations may have diminished. Although the prognostic impact of surgical margin status is somewhat more controversial, most but not all investigators were able to confirm the prognostic impact of this parameter in multivariate analyses [1, 2, 13, 15].

Another factor that may detract from the prognostic impact of pathological staging and determination of surgical margin is the degree of interobserver variation among pathologists. Most pathologists would agree that a substantial interobserver variation exists for grading of prostate cancer, but this issue has rarely been addressed for pathological staging and surgical margin status [7]. Prostatectomy specimens of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) trial 22911 were centrally reviewed as a part of the study protocol designed to study the potential benefit of postoperative external radiotherapy in patients with a pathological stage pT3 prostate cancer and/or positive surgical margins, while negative for locoregional or distant metastasis. The first results of this trial were published recently [3]. Here, we report on the degree of interobserver variation between local pathologists and review pathology (by a single pathologist) for pathological stage, including seminal vesicle invasion and extraprostatic extension, and for surgical margin status. In addition, the prognostic impact of these parameters was analyzed using biochemical recurrence-free survival (PSA failure after prostatectomy) as outcome parameter.

Materials and methods

Patients and surgical specimens

Prostatectomy specimens of 566 participants of the EORTC study 22911 were reviewed, of which 14 belonged to ineligible cases leaving a total of 552 cases (280 in the wait-and-see arm and 272 in the postoperative irradiation arm) eligible. In each participating center the protocol was approved by the local/national ethics review committee. Informed consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with national laws.

The total number of participants of this multiinstitutional trial was 1,005, but only the prostatectomy specimens of 11 major participating hospitals were reviewed.

After formalin fixation, the prostatectomy specimens were totally embedded after inking the outer surface of the specimens essentially using the same protocol for grossing in all participating hospitals [14, 16]. This includes separate embedding of parasagittal sections of the apex and bladder neck margin. Exclusion criteria for pathological review were hormonal therapy before prostatectomy or incomplete embedding of the prostatectomy.

Pathological review

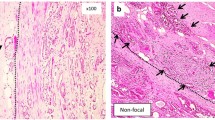

The pathological review was performed by a single pathologist with experience in urogenital pathology (THvdK) and included the examination of all slides of the radical prostatectomy specimen. In addition to Gleason score, pathological stage [Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) 1997], presence of extraprostatic extension, invasion of seminal vesicles, and surgical margin status were recorded. If extraprostatic (or extracapsular) extension was present, its extent [focal, i.e., extending <1 high power field (hpf), or otherwise extensive, i.e., >1 hpf] and sidedness were recorded. Extraprostatic extension was defined by either infiltration of the carcinoma of the prostatic pseudocapsule into the direct vicinity or beyond the adipose tissue (Fig. 1a) or within the neurovascular bundle beyond the outer contour of the adjacent pseudocapsule (Fig. 1b). Bladder invasion was determined by invasion in the large bundles of smooth muscle, characteristic of the muscularis propria of the urinary bladder. Positive margin status was recorded in case of the presence of tumor cells within the inked margin. For positive surgical margin, apical and nonapical (designated as lateral) involvement was distinguished.

a Micrograph showing adipose tissue (solid arrow) at the edge of the pseudocapsule and a single tumor gland (double-line arrow) at the level of and beyond the adipose tissue fulfilling the requirement of extraprostatic extension. b Micrograph showing infiltration of neurovascular bundle by scattered foci of poorly differentiated carcinoma (double-line arrow). The contour of the outer edge of the prostatic pseudocapsule is depicted by the interrupted line. Although adipose tissue is not identified in the vicinity of the cancer, this is also considered extraprostatic extension

Follow-up and endpoint

Details of the follow-up of the EORTC trial 22911 were described elsewhere [3]. Clinical follow-up with digital rectal examination and PSA tests were done at 4, 8, and 12 months after treatment, then every 6 months until the end of the fifth year. Chest radiography and bone scans were done every year or in case of clinical or biochemical suspicion of progression. CT scans and liver ultrasound were used for confirmation of progression. Biochemical recurrence was defined as a PSA increase of more than 0.2 ng/ml over the lowest postoperative value measured on three occasions at least 2 weeks apart.

Local recurrence had to be documented by digital rectal examination.

The primary trial endpoint and endpoint of the present analysis is biochemical progression-free survival defined as the time from randomization to first clinical or biochemical recurrence or death due to any cause.

Statistics

Agreement between local pathology and review pathology on the 552 prostatectomy specimens was measured by the total percentage of agreement and by simple kappa statistics [4].

The prognostic value of staging parameters and surgical margin status defined by local and review pathology was analyzed on the 280 cases of the wait-and-see arm of the trial as postoperative irradiation will influence the biochemical and clinical progression-free interval [3]. The prognostic impact of local and review pathology for the different parameters was analyzed by Cox regression model [6] with estimation of hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals. Event-free rates were estimated by Kaplan–Meier [12].

Results

The median follow-up time for the 552 patients included in this analysis was 4.7 years. The age range of the patients varied between 47 and 75 years (median 66 years) and preoperative PSA level varied from 0.3 to 159.4 ng/ml (median 12.5 ng/ml) (Table 1). The patients included in this analysis had a slightly better overall prognosis than those excluded from the analysis (p=0.056), probably owing to differences in referral patterns between centers, as can be inferred from the lower rate of positive surgical margins and involvement of seminal vesicles.

Level of agreement between review and local pathology

A total of 552 radical prostatectomies were reviewed for extraprostatic extension, seminal vesicle invasion, and surgical margin status. Review data were not available for extraprostatic extension, seminal vesicle invasion, and surgical margin status in 5, 9, and 28 cases, respectively. This was due to incomplete sets of slides or impossibility of interpretation of the histological slides.

Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5 show that the agreement and corresponding kappa value is good for seminal vesicle invasion (Table 2), but mediocre for extraprostatic extension (Table 3) and surgical margin status (Table 4).

The local pathology more frequently judged a case positive for extraprostatic extension (78.1%, 421/552) than the review pathologist (54.5%, 301/552). The review pathologist did not find extraprostatic extension in 35% of the cases judged as extraprostatic extension by local pathology (151/431). In contrast, 19% of the cases scored without extraprostatic extension by local pathology were considered positive for extraprostatic extension by review pathology (23/121).

Surgical margin involvement was recorded in 53.3% by the review pathologist (294/552) and in 58.9% by local pathology (325/552). Negative margins as judged by local pathology were scored positive by review pathology in 26.4% of the cases (60/227) and conversely, 24.9% of the cases that scored positive by local pathology (81/325) were judged negative by the review pathology.

The level of agreement between local and review pathology was similar when the analysis was restricted to the four hospitals contributing more than 75 patients each to the study. Among these four hospitals, however, a large variation in agreement with review pathology existed for extraprostatic extension and surgical margin status. For extraprostatic extension one hospital showed considerably less agreement with review pathology (κ=0.0) than the other three hospitals (κ>0.30). Excluding that hospital, the agreement was κ=0.42 (0.34–0.51). For surgical margin status, there was again significant heterogeneity among the large hospitals (p<0.0001), and agreement was κ=0.64, 0.51, 0.13, 0.18 with review pathology.

In a separate analysis we showed that the year of entry did not influence the level of agreement, neither did it influence seminal vesicle invasion, extraprostatic extension, or margin status (data not shown).

At review pathology a distinction was made between focal and extensive extraprostatic invasion. Analysis of the discrepancies between review and local pathology showed that when the 84 cases with focal extension only were excluded (i.e., only extensive extraprostatic extension at review was considered), the agreement between review and local pathology remained essentially the same (κ=0.31 for extensive extraprostatic extension and κ=0.33 for all cases).

The breakdown of the surgical margin status results according to site is given in Table 4. If review pathology showed a positive surgical margin of the apex (n=126), the local pathology would also judge the margin positive in 83% of the cases, but this proportion dropped to 76% of the cases when only the lateral margin was involved, according to the review pathologist (128/168), and the local pathologist agreed on the negative margin status in only 65% of the cases scored negative by review pathology (149/203).

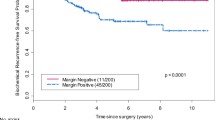

Influence of review pathology on the prognostic impact of staging parameters

Because postoperative radiotherapy influenced the long-term clinical outcome (biochemical progression-free survival and clinical recurrence), the analysis of the prognostic impact of local and review pathology was restricted to the wait-and-see arm of the trial (n=268 patients with review pathology). Kaplan–Meier analysis for biochemical progression-free survival showed that surgical margin status by review pathology was a stronger predictor compared to local pathology (Fig. 2). HR of positive margins by review pathology for biochemical recurrence was 2.16 (95% CI 1.43–3.26 and p<0.0002), while local pathology surgical margin status was not significantly related to biochemical recurrence (HR=1.08, 95% CI 0.74–1.56, and p>0.1) in univariate analysis.

For extraprostatic extension, including those with focal and extensive extension, review pathology demonstrated a significant difference (in univariate analysis) between the two subsets (HR=1.83, 95% CI 1.25–2.68, and p=0.0017), while local pathology was not able to demonstrate a significant difference (HR=1.05, 95% CI 0.66–1.68, and p>0.1).

Seminal vesicle involvement was a strong predictor of biochemical recurrence when assessed by the review pathologist (HR=2.03, 95% CI 1.33–3.10, and P=0.0008) and by the local pathologist (HR=1.99, 95% CI 1.35–2.95, and P=0.0004), owing to the very high agreement between the two assessments.

Discussion

Although it is frequently reported that grading of prostate cancer has a high interobserver variation, irrespective of the grading system used [10, 11] interobserver variation for staging parameters of radical prostatectomy specimens has rarely been investigated. Ekici et al. [7] studied a limited series of prostatectomy specimens from a single institution. They reported a high interobserver variation between the findings in the pathology report and those of the review pathologist, especially for surgical margin status and extraprostatic extension. Similarly, we demonstrate a surprisingly high rate of disagreement on a much larger series of radical prostatectomy specimens retrieved from several large institutions participating in this EORTC study (trial 22911).

All institutions adhered to a similar embedding pathology protocol, including total embedding of the prostatectomy specimen and allowing separate examination of apex and bladder neck, following the guidelines published before [14]. If the centers taken into account are only those attributing more than 75 cases to the trial, the level of (dis)agreement with review pathology remained essentially the same. It is most likely that the discrepancies can be attributed to differences in the interpretation of the findings and/or overlooking of some pathological details related to the investigated parameters. As for surgical margins, during review we strictly adhered to the guideline that tumor cells should really be in contact with ink to consider the margin positive, irrespective of the (minute) distance to the inked surface. This is in line with the finding of Epstein et al. [8] that a close margin (i.e.,<0.1 mm) should not be designated as positive surgical margin because this would not impact the prognosis. Also, lacerations in the capsule were accounted for as they may cause a false-positive diagnosis of positive margins, even though tumor cells may be covered by ink at these sites due to leakage. Similarly, presence of tumor cells in the outer surface of the specimen not covered by ink was not considered as evidence for a positive margin.

Current guidelines prescribe that only in the case of covering by ink (applied before the sectioning of the radical prostatectomy specimen) should the margin be considered as positive. It is important to note that application of these rules during our review led to the emergence of surgical margin status as a prognostic parameter, which was maintained after inclusion of the (reviewed) Gleason score in the multivariate analysis. Another potential source for discrepancies concerning the surgical margin status may be the assumption that the mere presence of carcinoma in sections of the apex would automatically signify a positive resection margin. This dates back to the time that in some institutions the apex was cut in a transversal plane precluding a proper evaluation of its resection margins. The observation that in our series the agreement at the apex margin status compared to lateral margin status is only marginally higher (Table 4) is not in line with this explanation.

Overlooking of extraprostatic extension may have played a role in the minority of the cases where review pathology recorded extraprostatic extension where local pathology failed to do so. In that case, comparatively more often, focal extraprostatic extension would be observed by review pathology than in the prostatectomies with consensus between review and local pathology concerning the presence of extraprostatic extension. Because this was not the case, this explanation for the higher frequency of extraprostatic extension during review cannot be maintained. Another potential source for discrepancy may be the judgment of tumor infiltrating the neurovascular bundle. The absence of adipose tissue may lead to underestimation of the presence of extraprostatic extension. Variation in agreement with central review among the four larger hospitals was considerable for both extraprostatic extension (one outlier) and surgical margin status (two outliers). This might suggest that different sets of criteria are being used in different pathology laboratories, while within a pathology laboratory the criteria are relatively uniform.

Similar to the paper by Ekici et al. [7], the level of agreement for seminal vesicle invasion was high. Apparently, most pathologists are aware of the requirement of tumor invasion of the muscular coat of the seminal vesicle in the extraprostatic part of the organ.

A potential limitation of this study may be that only pathological stage T3 cancers and/or those with a positive margin status (at local pathology) were included. Our conclusions are therefore likely to be valid particularly for the subset of patients with more advanced prostate cancer. Nevertheless, our study indicates that the observed strong interobserver variation for surgical margin status and extraprostatic extension bears consequences both directly for optimal patient care and for the outcome of trials on large groups of patients. A further search for the causes underlying the discrepancies is warranted to improve and further specify guidelines on reporting of radical prostatectomy specimens.

Review of radical prostatectomy specimens of participants of a trial is likely to improve the outcome of the study and should be an integrated part of any trial design.

References

Ackerman DA, Barry JM, Wicklund RA, Olson N, Lowe BA (1993) Analysis of risk factors associated with prostate cancer extension to surgical margin and pelvic node metastasis at radical prostatectomy. J Urol 150:1845–1850

Blute ML, Bostwick DG, Bergstralh EJ, Slezak JM, Martin SK, Amling CL, Zincke H (1997) Anatomic site-specific positive margins in organ-confined prostate cancer and its impact on outcome after radical prostatectomy. Urology 50:733–739

Bolla M, van Poppel H, Collette L, van Cangh P, Vekemans K, Da Pozzo L, de Reijke TM, Verbaeys A, Bosset JF, van Velthoven R, Marechal JM, Scalliet P, Haustermans K, Pierart M, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (2005) Postoperative radiotherapy after radical prostatectomy: a randomised controlled trial (EORTC trial 22911). Lancet 366:572–578

Cohen J (1960) A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas 20:37–46

Cooperberg MR, Lubeck DP, Mehta SS, Carroll PR, CaPSURE (2003) Time trends in clinical risk stratification for prostate cancer: implications for outcomes (data from CaPSURE). J Urol 170:S21–S25

Cox DR (1959) The analysis of exponentially distributed life-times with two types of failure. J R Stat Soc B 21:411–421

Ekici S, Ayhan A, Erkan I, Bakkaloğlu M, Őzen H (2003) The role of the pathologist in the evaluation of radical prostatectomy specimens. Scand J Urol Nephrol 37:387–391

Epstein JI, Sauvageot J (1997) Do close but negative margins in radical prostatectomy specimens increase the risk of postoperative progression? J Urol 157:241–243

Epstein JI, Amin M, Boccon-Gibod L, Egevad L, Humphrey PA, Mikuz G, Newling D, Nilsson S, Sakr W, Srigley JR, Wheeler TM, Montironi R (2005) Prognostic factors and reporting of prostate carcinoma in radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy specimens. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl 216:34–63

Gallee MP, Ten Kate FJ, Mulder PG, Blom JH, van der Heul RO (1990) Histological grading of prostatic carcinoma in prostatectomy specimens. Comparison of prognostic accuracy of five grading systems. Br J Urol 65:368–375

Glaessgen A, Hamberg H, Pihl CG, Sundelin B, Nilsson B, Egevad L (2002) Interobserver reproducibility of percent Gleason grade 4/5 in total prostatectomy specimens. J Urol 168:2006–2010

Kaplan EL, Meier P (1958) Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 53:457–481

Khan MA, Partin AW (2005) Surgical margin status after radical retropubic prostatectomy. BJU Int 95: 281–284

Montironi R, van der Kwast T, Boccon-Gibod L, Bono AV, Boccon-Gibod L (2003) Handling and pathology reporting of radical prostatectomy specimens. Eur Urol 44: 626–636

Palisaar RJ, Graefen M, Karakiewicz PI, Hammerer PG, Huland E, Haese A, Fernandez S, Erbersdobler A, Henke RP, Huland H (2002) Assessment of clinical and pathologic characteristics predisposing to disease recurrence following radical prostatectomy in men with pathologically organ-confined prostate cancer. Eur Urol 41:155–1561

Stamey TA, McNeal JE, Freiha FS, Redwine E (1988) Morphometric and clinical studies on 68 consecutive radical prostatectomies. J Urol 139:1235–1241

Van der Kwast TH, Ciatto S, Martikainen PM, Hoedemaeker R, Laurila M, Pihl CG, Hugosson J, Neetens I, Nelen V, Di Lollo S, Roobol MJ, Maatanen L, Santonja C, Moss S, Schroder FH (2006) Detection rates of high-grade prostate cancer during subsequent screening visits. Results of the European randomized screening study for prostate cancer. Int J Cancer 118:2538–2542

Acknowledgements

This publication was supported by grants number 5U10 CA488-21 to 5U10-CA488-34 from the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD, USA) and by a grant from Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (Comité de l’Isère, Grenoble, France). The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or of the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van der Kwast, T.H., Collette, L., Van Poppel, H. et al. Impact of pathology review of stage and margin status of radical prostatectomy specimens (EORTC trial 22911). Virchows Arch 449, 428–434 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-006-0254-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-006-0254-x