Abstract

Background

Over the last decades, surgeons, researchers, and health administrators have been working hard to define standards for high-quality treatment and care in Surgery departments. However, it is unclear whether patients’ perceptions of medical treatment and care are related and affected by surgeons’ perceptions of their working conditions and job satisfaction. The aim of this study was to evaluate patients’ satisfaction in relation to surgeons’ working conditions.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey with 120 patients and 109 surgeons working in Surgery hospital departments was performed. Surgeons completed a survey evaluating their working conditions and job satisfaction. Patients assessed quality of medical care and treatment and their satisfaction with being a patient in this department.

Results

Seventy percent of the patients were satisfied with performed surgeries and services in their department. Surgeons’ job satisfaction and working conditions rated with moderate scores. Bivariate analyses showed correlations between patients’ satisfaction and surgeons’ job satisfaction and working conditions. Strongest correlations were found between kindness of medical staff, treatment outcome and overall patient satisfaction.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates strong associations between surgeons’ working conditions and patient satisfaction. Based on these findings, hospital managements should improve work organization, workload, and job resources to not only improve surgeons’ job satisfaction but also quality of medical treatment and patient satisfaction in Surgery departments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During the last decade, an increased effort has been made to evaluate quality of medical treatment in Surgery hospital departments [1–3]. In addition, an increasing amount of research studies on surgical patient satisfaction with medical care and treatment have been performed [4–7]. Central dimensions in evaluation are fulfillment of patients’ health care needs and requests in Surgery hospital departments. Patient satisfaction is described as a combination of patients’ expectations regarding medical treatment, care, and their former experiences [8].

Previous studies investigated aspects of medical treatment and care in various medical fields which might have a great influence on patients’ evaluation and satisfaction [9–11].

In particular, a study by Schönfelder et al. [7] found factors which are associated with patient satisfaction in Surgery. The strongest predictors for patient satisfaction found in this study were interpersonal manners of medical practitioners and nurses, organization of operations, admittance, and discharge, as well as perceived length of stay [7].

Further studies mentioned perceptions of quality of medical treatment, clinic-organization of medical procedures and care, medical staffs’ kindness and professionalism, etc. as factors which have been shown to influence patient satisfaction in various medical fields [12, 13].

A study by Grol et al. [14] has demonstrated that general practitioners’ job satisfaction is also associated with patient satisfaction. Moreover, a study by Szecsenyi et al. [15] found also significant correlations between patient satisfaction and health care professionals.

Few published studies also focused on associations between hospital working environments and patient satisfaction in special medical fields (e.g., psychiatric wards). These previously published studies illustrated that patients being treated in hospital departments with high standards of work organization, social and cooperative support and low levels of conflicts or aggression were more satisfied [16, 17].

In addition, several studies have focused on relations between working environment and medical staffs’ satisfaction [18–21]. Attention has been drawn to this research field because associations have been found to turnovers, performance and treatment outcomes (e.g., medical errors), hospital financial outcomes (cost-effectiveness). In consequence, these factors are of great importance not only for each hospital management but also for health services in general [22–25].

Previous studies carried out in German hospitals analyzed doctors’ working conditions and job satisfaction in various hospitals [26–37]. A number of studies focused on German emergency departments using surveys on the quality of medical treatment to evaluate hospital performance and working environments [38–40]. These studies all demonstrated that working conditions such as excessive workloads can have a negative influence on general practice performance, treatment outcomes and medical errors [41–44]. In contrast, only few studies researched on the influence of positive working conditions (job resources) on treatment outcomes or patient satisfaction.

It is reasonable to assume that surgeons’ job satisfaction may influence the work environment and thus the quality of medical treatment in Surgery departments in total. Also, working conditions may influence surgeons’ satisfaction and patient satisfaction with treatment and care.

With regard to this, relations between surgeons’ assessment of their working conditions, job satisfaction and patients’ satisfaction with medical care are of great interest for health services. However, to our knowledge, in Germany, no study exists focusing on patients’ satisfaction with medical treatment in Surgery departments in relation to assessments of surgeons’ job satisfaction.

Results can give a first impression on how important satisfied surgeons are in relation to satisfactory medical treatment. In consequence, measures of patients’ and surgeons’ satisfaction can be used to redesign and optimize work schedules and organization of medical treatment in Surgery departments. All in all, information on this can be useful to improve the overall quality of care in Surgery.

Aims

The present research study aimed at focusing on interrelationships between working conditions, surgeons’ job satisfaction and patient satisfaction.

Regarding this, the aims of this study are (a) to investigate levels of surgeons’ job satisfaction, patients’ satisfaction with medical care in Surgery departments and (b) to analyze correlations between perceived working conditions and these two outcome parameters.

The following research questions are answered in our study:

-

1.

How do (a) patients evaluate their satisfaction with medical treatment and care in Surgery departments and (b) surgeons their job satisfaction?

-

2.

How do physicians evaluate their working conditions in Surgery departments?

-

3.

Is there a correlation between surgeons’ job satisfaction and patients’ satisfaction with medical treatment and care?

-

4.

Is there correlation between surgeons perceived working conditions and patients’ satisfaction with medical treatment and care?

Methods

Study design and setting

This study was conducted as a cross-sectional study conducted between 2009 and 2010 in seven General and Visceral Surgery hospital departments in Germany.

The hospital departments were comparable in number of patients/beds and size as far as employed doctors and other medical staff (e.g., nurses). The participating hospitals were all run by non-profit organizations. We did not include university hospitals in order to ensure comparability between the hospitals. Surgical procedures performed by the participating hospitals are illustrated in Table 1.

Participants

All participating surgeons were full-time employed junior doctors or residents specializing in Surgery (general and visceral surgery). Inclusion criterion in this study was: having at least 1 year of work experience in Surgery. One hundred fifty surgeons were requested to fill in an anonymous questionnaire. Participants in our study population were patients receiving Surgery services in hospital. 250 patients were asked to take part in our study.

Data collection

First we presented our study design to surgeons during clinical conferences/meetings. In addition, we informed patients by handing information hand-outs about the purposes and procedures of this study. After this procedure we scheduled dates for administering the survey. In addition, we got a list of patients being at the department at this time and their attending physician. Afterwards potential candidates for our study were recruited by asking patients and their attending doctors of each Surgery department if they are interested to participate in our study. Patients were given a questionnaire and a consent form at the end of their hospital stay. In addition, surgeons were given a questionnaire as well as the consent form.

All questionnaires and consent forms were then collected by our researchers or if participants needed more time they were returned to boxes at the hospitals.

Variables

We included several independent variables in our study: working demands and working resources, etc. (see Tables 2 and 3). Independent variables are the variables that were varied by us as presumed predictors. In our study patient satisfaction and job satisfaction are dependent variables (response that is measured as presumed effects).

Patients’ socio-demographic characteristics might affect their ratings on satisfaction with treatment and care. To control for these mediating variables, we used patients’ data regarding for example, their age, race, gender, length of stay, number of surgical treatments performed. In addition, we also controlled physicians’ age, gender, years of experience, marital status and having children status.

Questionnaires

Working conditions and job satisfaction was evaluated by using the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ) [45]. In addition, patients’ perceptions of medical quality, evaluation of the clinical stay etc. were asked by using a self-assessment questionnaire.

Patient satisfaction questionnaire

The survey used in this study is a general self-assessment questionnaire including a number of questions about perception of medical treatment and care, overall satisfaction with the hospital stay. In addition, the questionnaire included information regarding admission, effects of length of hospital stay, service aspects and motivation to return to this hospital department in case of a readmission (Table 1).

Patients’ evaluation was reported by individual scale items. Each item was scored as an adjectival Likert scale (five categories: 1 = poor, 2 = average, 3 = good, 4 = very good, and 5 = excellent).

We also validated the questionnaire: our results demonstrated that the patient questionnaire is reliable, valid, and practicable.

Cronbach's alpha coefficients for the items ranged from α = 0.70 to α = 0.85. The Intraclass correlation (ICC) values for the subscales varied between 0.82 and 0.90. The ICC values for the items ranged between 0.73 and 0.88.

To evaluate the convergent validity we related the patient satisfaction variables to what it should theoretically be related to. To show the convergent validity of the patient satisfaction questionnaire, the scores on the test were correlated with scores on other tests that are also designed to measure patient satisfaction. High correlations between the test scores would be evidence of a convergent validity.

We performed a pre-study with a sample of 100 surgery patients in hospital and correlated the sum score of our questionnaire with the sum score of the Zurich Questionnaire [46]. Correlation scores were r > 0.70 pointing to an acceptable convergent validity of the questionnaire.

To assess construct validity, two pairs of items were chosen from two different subscales [47]. The items of each pair had to be related to and dependent on each other (r > 0.30), while the items of the different pairs were not related (r < 0.30) [48].

Factor analysis with varimax rotation showed a two-dimensional structure. The first factor grouped ten items containing aspects about medical treatment (surgery procedures), satisfaction with outcome (after surgery), and organizational aspects (approx. 43 % of the variance). The second factor contained aspects on medical care and service (approx. 21 % of the variance).

Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire

The COPSOQ (German version) was used to evaluate surgeons working conditions (job demands and job resources). Table 3 presents the scales used in this study.

We also checked and validated the COPSOQ although researchers have done this previously [49, 50]. Our results confirm reliability, validity and applicability of the COPSOQ, scores were satisfactory. Cronbach's alpha coefficients for the items ranged between α = 0.73 and 0.84 and all intercorrelations were measured between r = 0.40 and 0.72.

All items relating to working conditions and their outcomes (e.g., working demands, working resources, and job satisfaction) were transformed to a scale ranging from 0 (“do not agree at all”) to 100 (“fully agree”) [37]. The category “does not apply” and item non-response were coded as missing data.

Statistical methods

We analyzed descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations). In addition, we analyzed the data with regard to their distribution. We consequently used parametric and non-parametric tests (T tests, Mann–Whitney U tests, Pearson and Spearman correlation analyses). All differences or correlations were considered to be statistically significant at p < 0.05-level.

Confounders (mediating variables) were controlled by using Sobel's test statistic; additional logistic regression analyses were carried out. In addition, we constructed regression models.

In general, we used the PASW® software package for statistical analyses.

Results

Of the 400 administered questionnaires, 55 % valid questionnaires were returned (n = 220). Return rates varied by group: 98 of the surgeons and 122 of the patients returned the questionnaires.

Patients’ characteristics

The majority of the patients were male (62 %); 55 % were married, 51 % had children. Patients’ age ranged between 28 and 82 years (mean = 43; SD = 6.4).

About 89 % of all participating patients were admitted by a specialist or by their general practitioner, 1 % was transferred from another clinic, and about 1 % reported self-admission. Nine percent of the patients did not answer this question.

A percentage of 74 of the patient sample evaluated the length of stay to be appropriate, 11 % reported their length to be inappropriate (too long or too short), and 15 % did not answer this question. Sixteen percent considered their hospital stay to be too short, 3 % to be too long, 8 % did not answer this question.

Medical complications after surgery were reported by 19 % of the patients. A percentage of 72 of all patients would use this specific surgery hospital department again.

Physicians’ characteristics

The study sample included 41 % female physicians and 59 % male physicians. 30 % were single and 41 % had no children. Age ranged from 27 to 54 years (M = 33; SD = 5.12). The mean number of physicians’ experience in the current job was M = 4.15 years, SD = 2.26 years.

Patient satisfaction

The results showed that about 70 % of the patients were satisfied with performed medical treatments and services in their Surgery department; that means they evaluated with good scores. Mean for overall satisfaction was M = 3.1 (SD = 0.91; Table 2).

Patients’ satisfaction with various dimensions of medical treatment (e.g., satisfaction with staff, treatment, organizational procedures) ranges between 2.67 and 3.23. Mean scores and standard deviations for the subscales are presented in Table 2.

Correlations between patient demographics, satisfaction and visit characteristics

We found that gender was not significantly correlated with patient satisfaction: significant differences between male and female patients’ satisfaction ratings were found.

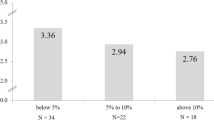

We also analyzed age differences and found that the patients' age was related to assessments of satisfaction (p < 0.05). A positive correlation between increase of age and patient satisfaction was found. Figure 1 illustrates groups of patients differentiated with regard to their age. Correlation tests showed that the association between age and patient satisfaction is not linear. Significant differences did not occur between all included age groups. Younger patients in particular (<25) differed the most compared to older patients >60 years (p < 0.05).

Our results also showed a significant difference in reported satisfaction between patients complaining about medical complications and patients without medical difficulties. The first group evaluated their overall satisfaction as less satisfied (M = 2.6) in comparison to patients without complications (M = 3.6; p < 0.01). In addition, those patients with complications also reported a significant lower motivation to return to this hospital department in case of a further readmission than patients without medical difficulties (p < 0.05). Patients who were satisfied with the length of their hospital stay also showed more overall satisfaction (M = 3.8) than patients who evaluated their hospital stay with being too short (3.1), or too long (3.2, p < 0.05).

Surgeons’ satisfaction ratings and working conditions

Evaluations of working demands and working resources are illustrated in Table 3. Working demands such as working under pressure have been validated as high in all seven hospital departments (M = 70.38, SD = 13.12). Emotional demands were evaluated as stressful (M = 67.52, SD = 13.56). Job resources were rated with scores between M = 34.68 and 67.59. The highest scores were reported for “possibilities for development” (M = 67.59, SD = 13.10) and “social support from colleagues” (M = 65.67, SD = 14.38). Receiving “feedback at work” was scored lowest with M = 34.68, SD = 16.62.

Surgeons rated their job satisfaction with moderate scores (M = 59.34; SD = 13.81; see Table 3). In addition, we analyzed associations between surgeons’ working conditions and their perceived job satisfaction. Table 4 illustrates these associations: job demands (quantitative job demands; working under pressure) correlated significantly negative to surgeons’ job satisfaction. That means surgeons who scored their job demands as high valued their job satisfaction low. In addition, our findings illustrated positive correlations between perceived job resources and job satisfaction. Surgeons who scored high at items such as “having influence at work”, “possibilities for development”, “social support” etc. valued their job satisfaction high (see Table 4).

Bivariate analyses

Bivariate analyses showed correlations between patients’ overall satisfaction and surgeons’ job satisfaction (r = 0.49, p < 0.01). The higher surgeons rated their job satisfaction the higher patients rated their overall satisfaction.

Moreover, our results showed that the better surgeons have rated their working conditions the better patients evaluated their satisfaction. In detail, analyses showed significant negative correlations between physicians’ assessments of their working demands and patient satisfaction (r = −0.38; p < 0.01). In contrast, positive correlations were analyzed between working resources (social support, feedback, etc.) and patient satisfaction (r = 0.42, p < 0.01).

Confounder analyses

Confounder analyses showed that the included independent variables were not significantly related to the mediating variables (p > 0.05). In addition, the mediating variables were not significantly related to the dependent variables (job and patient satisfaction; p > 0.05).

Discussion

As far as we know, this is the first German study investigating associations between physicians’ job satisfaction, working conditions and patient satisfaction with hospital care.

Study limitations

Some limitations of this study should be mentioned. First, the sample may not be representative for all Surgery departments in Germany. Additional investigations with a greater number of participants in various territories should be done. Second, study design was cross-sectional which limits the generalizability of our results. In general, cross-sectional analyses are of limited value in supporting causal effects [48]. Factors such as working conditions can change over time and might influence findings. Further studies including longitudinal analyses are advised to present supplementary information for the associations between job satisfaction, hospital working environment and patient satisfaction.

In addition, some questions of the patient satisfaction questionnaire might be too general and need to be adapted to give (1) specific details for medical care/treatment in Surgery and (2) more specialized information about patient needs. A supplementary qualitative study should be conducted. In doing so, more specific personal aspects which might influence patient satisfaction could be investigated.

Patient satisfaction

Regarding patient satisfaction our findings are concordant to prior performed studies. These findings were similar in particular for age differences [51–54]. Older patients tended to be more satisfied than younger patients. In contrast to our results, previous research also found significant gender differences [55–58].

In line with other previous studies, our results indicate that professional medical treatment has highly positive effects on patient satisfaction [59–61]. In contrast, different studies also showed that medical complications are strong predictors for patient dissatisfaction [62, 63]. Post-discharge complications can be seen as a generalizable factor for dissatisfaction.

Our results also revealed that patients with shorter lengths of hospital stay were more satisfied than patients who reported that their hospital stay was “too long”. This result is also consistent with previously performed studies in various medical fields [58, 64, 65].

Kindness of health care professionals and communication between patient and attending physician were mentioned in several studies as important factors for satisfied patients [66–69]. Unfortunately, as shown in our previously performed time and motion studies, little time has been used for doctor–patient interaction [28, 29, 31–34]. Work overload, pressures associated with numerous working demands can lead to less time spent on doctors’ patient talk [70]. A study performed by Argentero et al. [71] gave evidence of significant associations between kindness in medical practice (e.g., towards patients and their relatives) and physicians’ workload and emotional exhaustion.

Physicians working conditions and job satisfaction

Our assessments of working demands and resources are comparable to research previously investigated in other related medical fields (e.g. Internal Medicine, Pediatrics and Radiotherapy) [37, 72–74]. Evaluations of job satisfaction are also concordant with other studies having investigated this job outcome [37, 73, 75].

As discussed in prior publications, current working conditions and work environment in health services (e.g., financial restrictions, reductions in hospital staff members) reduce doctors’ job satisfaction in general [25, 76] and particularly with regard to Germany [37, 73].

Associations between physicians’ working conditions, job satisfaction, and patient satisfaction

One of our research questions referred to whether there are associations between surgeons working conditions/job satisfaction and patient satisfaction. The findings showed that surgical patient satisfaction is related to physicians’ perception of their work environment and their job satisfaction. Results have demonstrated that surgical patients are less satisfied in hospitals where surgeons reported unsatisfactory, unacceptable working conditions and reduced job satisfaction. Former studies performed by several researchers, as mentioned above, showed that satisfied medical staff has a strong influence on patients’ satisfaction [77–79].

With regard to the results of the present study, reorganization of schedules and hospital department structures might have the potential to improve the workplace for physicians and at the same time improve patient satisfaction with clinical care. More and regular job resources such as social support and constructive/helpful feedback should be guaranteed in every hospital department. In addition, a continuous supervision (expert consultations) and mentoring programs can support medical staff [80–82].

Remarkably, associations between surgeons’ job satisfaction and patients’ satisfaction can also indicate that satisfied patients can make doctors happier and more satisfied with their jobs. Patients’ satisfaction might also reflect having performed high-quality care.

Our findings also indicate that kindness of medical staff is highly correlated with the overall satisfaction of patients. Additional studies also demonstrated that patient satisfaction is mainly influenced by “communication with doctors and kindness of medical staff” [83]. Unfortunately, surgeons working under constant time pressure and handling more than one medical task at the same time have less time for individual contact with patients.

Prior studies demonstrated that on average only 10 % of the time during an average working day were spent on direct patient care [28, 30, 34]. It is well known that work overload, working under pressure, and multitasking, reduce the time for direct patient communication [84, 85]. Moreover, such a working environment can also decrease kindness of medical staff, a fact that has been illustrated by several studies [86–88].

However, it is important to note the fact that the present study did not investigate the direction of causality. On the basis of our investigation it is not clear, whether (1) satisfied surgeons have a positive influence on patients’ satisfaction or (2) whether satisfied patients make surgeons more satisfied with their jobs, or (3) also possible, both samples have an influence on each others’ satisfaction.

Conclusion

This study gives valuable information on relations between perceived working conditions and perceptions of patients’ satisfaction with clinical practice. Results revealed that physicians’ working conditions are related to both physicians’ job satisfaction and patient satisfaction.

In addition, our results demonstrated that healthcare professionals need to be attentive to the needs of each individual patient. This study illustrates the need for health care administrators to focus more on hospital management practices of their organization and efforts to improve the quality of medical care by changing employee working conditions, and satisfaction.

References

Lantz PM, Janz NK, Fagerlin A, Schwartz K, Liu L, Lakhani I, Salem B, Katz SJ (2005) Satisfaction with surgery outcomes and the decision process in a population-based sample of women with breast cancer. Health Serv Res 40:745–767

Ellison LM, Pinto PA, Kim F, Ong AM, Patriciu A, Stoianovici D, Rubin H, Jarrett T, Kavoussi LR (2004) Telerounding and patient satisfaction after surgery. J Am Coll Surg 199:523–530

Myles PS, Williams DL, Hendrata M, Anderson H, Weeks AM (2000) Patient satisfaction after anaesthesia and surgery: results of a prospective survey of 10,811 patients. Br J Anaesth 84:6–10

Hildebrand P, Duderstadt S, Jungbluth T, Roblick UJ, Bruch HP, Czymek R. Evaluation of the quality of life after surgical treatment of chronic pancreatitis. Jop 12:364–371

Braun KP, Braun V, Brookman-Amissah S, May M, Ptok H, Lippert H, Gastinger I (2009) Treatment of rectal carcinoma: satisfaction of general practitioners with surgical clinics. Chirurg 80:1147–1151

Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, Sandler HM, Northouse L, Hembroff L, Lin X, Greenfield TK, Litwin MS, Saigal CS et al (2008) Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med 358:1250–1261

Schoenfelder T, Klewer J, Kugler J. Factors associated with patient satisfaction in surgery: the role of patients' perceptions of received care, visit characteristics, and demographic variables. J Surg Res 164:e53–e59

Dowd BE, Kralewski JE, Kaissi AA, Irrgang SJ (2009) Is patient satisfaction influenced by the intensity of medical resource use by their physicians? Am J Manag Care 15:e16–e21

Valenstein M, Mitchinson A, Ronis DL, Alexander JA, Duffy SA, Craig TJ, Barry KL (2004) Quality indicators and monitoring of mental health services: what do frontline providers think? Am J Psychiatry 161:146–153

Kelson M (1996) User involvement in clinical audit: a review of developments and issues of good practice. J Eval Clin Pract 2:97–109

Castillo L, Dougnac A, Vicente I, Munoz V, Rojas V (2007) Predictors of the level of patient satisfaction in a university hospital. Rev Med Chil 135:696–701

Middelboe T, Schjodt T, Byrsting K, Gjerris A (2001) Ward atmosphere in acute psychiatric in-patient care: patients' perceptions, ideals and satisfaction. Acta Psychiatr Scand 103:212–219

Corrigan PW (1990) Consumer satisfaction with institutional and community care. Community Ment Health J 26:151–165

Grol R, Mokkink H, Smits A, van Eijk J, Beek M, Mesker P, Mesker-Niesten J (1985) Work satisfaction of general practitioners and the quality of patient care. Fam Pract 2:128–135

Szecsenyi J, Goetz K, Campbell S, Broge B, Reuschenbach B, Wensing M. Is the job satisfaction of primary care team members associated with patient satisfaction? BMJ Qual Saf 20:508-514

Friis S (1986) Characteristics of a good ward atmosphere. Acta Psychiatr Scand 74:469–473

Rossberg JI, Friis S (2003) A suggested revision of the ward atmosphere scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 108:374–380

Djukic M, Kovner CT, Brewer CS, Fatehi FK, Cline DD (2011) Work environment factors other than staffing associated with nurses' ratings of patient care quality. Health Care Manage Rev

Gulliver P, Towell D, Peck E (2003) Staff morale in the merger of mental health and social care organizations in England. J Psychiatry Ment Health Nurs 10:101–107

Zhang Y, Feng X (2011) The relationship between job satisfaction, burnout, and turnover intention among physicians from urban state-owned medical institutions in Hubei, China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 11:235

Shelledy DC, Mikles SP, May DF, Youtsey JW (1992) Analysis of job satisfaction, burnout, and intent of respiratory care practitioners to leave the field or the job. Respir Care 37:46–60

Grayson D, Boxerman S, Potter P, Wolf L, Dunagan C, Sorock G, Evanoff B et al (2005) Do transient working conditions trigger medical errors? research findings. In: Henriksen K, Battles J, Marks E, Lewin D (eds) Advances in patient safety: from research to implementation. Volume 1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), Rockville

Warwicker T (1998) Managerialism and the British GP: the GP as manager and as managed. J Manag Med 12:331–348, 320

Dahlin M, Fjell J, Runeson B (2010) Factors at medical school and work related to exhaustion among physicians in their first postgraduate year. Nord J Psychiatry 64:402–408

Musich S, Hook D, Baaner S, Spooner M, Edington DW (2006) The association of corporate work environment factors, health risks, and medical conditions with presenteeism among Australian employees. Am J Health Promot 21:127–136

Hauschild I, Vitzthum K, Klapp BF, Groneberg DA, Mache S (2011) Time and motion study of anesthesiologists' workflow in German hospitals. Wien Med Wochenschr 161:433–440

Kloss L, Musial-Bright L, Klapp BF, Groneberg DA, Mache S (2010) Observation and analysis of junior OB/GYNs' workflow in German hospitals. Arch Gynecol Obstet 281:871–878

Mache S, Bernburg M, Scutaru C, Quarcoo D, Welte T, Klapp BF, Groneberg DA (2009) An observational real-time study to analyze junior physicians' working hours in the field of gastroenterology. Z Gastroenterol 47:814–818

Mache S, Busch D, Vitzthum K, Kusma B, Klapp BF, Groneberg DA (2011) Cardiologists' workflow in small to medium-sized German hospitals: an observational work analysis. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 12:475–481

Mache S, Jankowiak N, Scutaru C, Groneberg DA (2009) Always out of breath? An analysis of a doctor's tasks in pneumology. Pneumologie 63:369–373

Mache S, Kelm R, Bauer H, Nienhaus A, Klapp BF, Groneberg DA (2010) General and visceral surgery practice in German hospitals: a real-time work analysis on surgeons' work flow. Langenbecks Arch Surg 395:81–87

Mache S, Kloss L, Heuser I, Klapp BF, Groneberg DA (2011) Real time analysis of psychiatrists' workflow in German hospitals. Nord J Psychiatry 65:112–116

Mache S, Kusma B, Vitzthum K, Nienhaus A (2012) Klapp BF. Groneberg DA: Analysis and evaluation of geriatricians' working routines in German hospitals Geriatr Gerontol Int 12:108–115

Mache S, Schoffel N, Kusma B, Vitzthum K, Klapp BF, Groneberg DA (2011) Cancer care and residents' working hours in oncology and hematology departments: an observational real-time study in German hospitals. Jpn J Clin Oncol 41:81–86

Mache S, Vitzthum K, Klapp BF, Groneberg DA (2011) Doctors' working conditions in emergency care units in Germany: a real-time assessment. Emerg Med J

Mache S, Vitzthum K, Kusma B, Nienhaus A, Klapp BF, Groneberg DA (2010) Pediatricians' working conditions in German hospitals: a real-time task analysis. Eur J Pediatr 169:551–555

Mache S, Vitzthum K, Nienhaus A, Klapp BF, Groneberg DA (2009) Physicians' working conditions and job satisfaction: does hospital ownership in Germany make a difference? BMC Health Serv Res 9:148

Christ M, Dodt C, Geldner G, Hortmann M, Stadelmeyer U, Wulf H (2010) Presence and future of emergency medicine in Germany. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther 45:666–671

Blaschke S, Muller GA, Bergmann G (2008) Reorganization of the interdisciplinary emergency unit at the university clinic of Gottingen. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther 43:314–317

Weltermann B, vom Eyser D, Kleine-Zander R, Riedel T, Dieckmann J, Ringelstein EB (1999) Supply of emergency physicians for patients with stroke in the Munster area. A cross-sectional study of the quality of regional health care. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 124:1192–1196

van den Hombergh P, Kunzi B, Elwyn G, van Doremalen J, Akkermans R, Grol R, Wensing M (2009) High workload and job stress are associated with lower practice performance in general practice: an observational study in 239 general practices in the Netherlands. BMC Health Serv Res 9:118

Brady AM, Malone AM, Fleming S (2009) A literature review of the individual and systems factors that contribute to medication errors in nursing practice. J Nurs Manag 17:679–697

Montgomery VL (2007) Effect of fatigue, workload, and environment on patient safety in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med 8:S11–S16

Fernandez Taylor KR (2007) Excessive work hours of physicians in training in El Salvador: putting patients at risk. PLoS Med 4:e205

Kristensen TS, Hannerz H, Hogh A, Borg V (2005) The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire—a tool for the assessment and improvement of the psychosocial work environment. Scand J Work Environ Health 31:438–449

Schmidt J, Lamprecht F, Wittmann WW (1989) Satisfaction with inpatient management. Development of a questionnaire and initial validity studies. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 39:248–255

Trochim W, Donnelly J (2008) The research methods knowledge base. Mason, USA

Bortz J (2007) Statistik. Für human- und sozialwissenschaftler. Springer, Berlin

Nuebling M, Hasselhorn HM (2010) The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire in Germany: from the validation of the instrument to the formation of a job-specific database of psychosocial factors at work. Scand J Public Health 38:120–124

Bjorner JB, Pejtersen JH (2010) Evaluating construct validity of the second version of the Copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire through analysis of differential item functioning and differential item effect. Scand J Public Health 38:90–105

Jaipaul CK, Rosenthal GE (2003) Are older patients more satisfied with hospital care than younger patients? J Gen Intern Med 18:23–30

Rahmqvist M (2001) Patient satisfaction in relation to age, health status and other background factors: a model for comparisons of care units. Int J Qual Health Care 13:385–390

Rahmqvist M, Bara AC (2011) Patient characteristics and quality dimensions related to patient satisfaction. Int J Qual Health Care 22:86–92

Finkelstein BS, Singh J, Silvers JB, Neuhauser D, Rosenthal GE (1998) Patient and hospital characteristics associated with patient assessments of hospital obstetrical care. Med Care 36:AS68–AS78

Schmittdiel J, Grumbach K, Selby JV, Quesenberry CP Jr (2000) Effect of physician and patient gender concordance on patient satisfaction and preventive care practices. J Gen Intern Med 15:761–769

Gross R, McNeill R, Davis P, Lay-Yee R, Jatrana S, Crampton P (2008) The association of gender concordance and primary care physicians' perceptions of their patients. Women Health 48:123–144

Bertakis KD (2009) The influence of gender on the doctor–patient interaction. Patient Educ Couns 76:356–360

Binsalih SA, Waness AO, Tamim HM, Harakati MS, Al Sayyari AA (2011) Inpatients' care experience and satisfaction study. J Fam Community Med 18:111–117

Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R (2011) Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care 17:41–48

Glickman SW, Boulding W, Manary M, Staelin R, Roe MT, Wolosin RJ, Ohman EM, Peterson ED, Schulman KA (2010) Patient satisfaction and its relationship with clinical quality and inpatient mortality in acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 3:188–195

Liu SS, Amendah E, Chang EC, Pei LK (2008) Satisfaction and value: a meta-analysis in the healthcare context. Health Mark Q 23:49–73

Agoritsas T, Bovier PA, Perneger TV (2005) Patient reports of undesirable events during hospitalization. J Gen Intern Med 20:922–928

Downey-Ennis K. Patient satisfaction. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 24:196–197

Nguyen Thi PL, Briancon S, Empereur F, Guillemin F (2002) Factors determining inpatient satisfaction with care. Soc Sci Med 54:493–504

Tokunaga J, Imanaka Y (2002) Influence of length of stay on patient satisfaction with hospital care in Japan. Int J Qual Health Care 14:493–502

Moore P, Vargas A, Nunez S, Macchiavello S (2011) A study of hospital complaints and the role of the doctor–patient communication. Rev Med Chil 139:880–885

Seiler A, Visintainer P, Brzostek R, Ehresman M, Benjamin E, Whitcomb W, Rothberg MB (2011) Patient satisfaction with hospital care provided by hospitalists and primary care physicians. J Hosp Med

Cousin G, Schmid Mast M, Roter DL, Hall JA (2011) Concordance between physician communication style and patient attitudes predicts patient satisfaction. Patient Educ Couns

Thornton RL, Powe NR, Roter D, Cooper LA (2011) Patient–physician social concordance, medical visit communication and patients' perceptions of health care quality. Patient Educ Couns 85:e201–e208

Rodin G, Mackay JA, Zimmermann C, Mayer C, Howell D, Katz M, Sussman J, Brouwers M (2009) Clinician–patient communication: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 17:627–644

Argentero P, Dell'Olivo B, Ferretti MS (2008) Staff burnout and patient satisfaction with the quality of dialysis care. Am J Kidney Dis 51:80–92

Sehlen S, Vordermark D, Schafer C, Herschbach P, Bayerl A, Pigorsch S, Rittweger J, Dormin C, Bolling T, Wypior HJ et al (2009) Job stress and job satisfaction of physicians, radiographers, nurses and physicists working in radiotherapy: a multicenter analysis by the DEGRO Quality of Life Work Group. Radiat Oncol 4:6

Rosta J, Gerber A (2008) Job satisfaction of hospital doctors. Results of a study of a national sample of hospital doctors in Germany. Gesundheitswesen 70:519–524

Buddeberg-Fischer B, Klaghofer R, Abel T, Buddeberg C (2005) Junior physicians' workplace experiences in clinical fields in German-speaking Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly 135:19–26

Lux G, Stabenow-Lohbauer U, Langer M, Bozkurt T (1996) Gastroenterology in Germany—determination of current status and perspectives. Results of a survey among members of the German Society of Digestive and Metabolic Diseases. Z Gastroenterol 34:542–548

Yu S, Gu G, Zhou W, Wang S (2008) Psychosocial work environment and well-being: a cross-sectional study at a thermal power plant in China. J Occup Health 50:155–162

Corrigan PW, Lickey SE, Campion J, Rashid F (2000) Mental health team leadership and consumers satisfaction and quality of life. Psychiatr Serv 51:781–785

DiMatteo MR, Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, Ordway L, Kravitz RL, McGlynn EA, Kaplan S, Rogers WH (1993) Physicians' characteristics influence patients' adherence to medical treatment: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Health Psychol 12:93–102

Giupponi G, Hensel S, Muller P, Soelva M, Schweigkofler H, Steiner E, Pycha R, Moller-Leimkuhler AM (2009) The patient's satisfaction in relation with the treatment in hospital psychiatry: a comparison between Italy and Germany. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 77:346–352

Kalen S, Ponzer S, Silen C (2011) The core of mentorship: medical students' experiences of one-to-one mentoring in a clinical environment. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract

Stamm M, Buddeberg-Fischer B (2011) The impact of mentoring during postgraduate training on doctors' career success. Med Educ 45:488–496

Gil KM, Savitski JL, Bazan S, Patterson LR, Kirven M (2009) Obstetrics and gynaecology chief resident attitudes toward teaching junior residents under normal working conditions. Med Educ 43:907–911

Sitzia J, Wood N (1997) Patient satisfaction: a review of issues and concepts. Soc Sci Med 45:1829–1843

Weigl M, Muller A, Zupanc A, Angerer P (2009) Participant observation of time allocation, direct patient contact and simultaneous activities in hospital physicians. BMC Health Serv Res 9:110

Arora S, Sevdalis N, Nestel D, Woloshynowych M, Darzi A, Kneebone R (2010) The impact of stress on surgical performance: a systematic review of the literature. Surgery 147:318–330, 330 e311-316

Alarcon GM, Lyons JB (2011) The relationship of engagement and job satisfaction in working samples. J Psychol 145:463–480

Mathieson F, Barnfield T, Young G (2009) What gets in the way of clinical contact? Student perceptions of barriers to patient contact. N Z Med J 122:23–29, quiz 29-31

Rousseau V, Aube C (2011) Social support at work and affective commitment to the organization: the moderating effect of job resource adequacy and ambient conditions. J Soc Psychol 150:321–340

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients and physicians for their participation.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mache, S., Vitzthum, K., Klapp, B.F. et al. Improving quality of medical treatment and care: are surgeons’ working conditions and job satisfaction associated to patient satisfaction?. Langenbecks Arch Surg 397, 973–982 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-012-0963-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-012-0963-3