Abstract

Background

The aim of this study is to present our experience and results with performing laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis evaluating the effect of timing of surgery and the influence of the various types of gallbladder inflammation on patient outcome.

Materials and methods

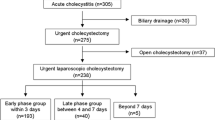

The patients were separated in three groups according to the time between the onset of symptoms and the operation: the “early” group was defined as laparoscopic cholecystectomy completed in the first 72 h after the onset of the symptoms, the “intermediate” group from 4 to 7 days, and the “delayed” group with symptoms lasting more than 8 days.

Results

Two hundred twenty-five patients underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy. There were 115 patients who underwent “early” surgery; 70 patients underwent “intermediate” surgery, and 70 patients underwent “delay” surgery. The total number of converted cases was 32 (12.5%). There were 124 cases of acute cholecystitis, 53 cases of gangrenous cholecystitis, 27 cases of hydrops, and 51 cases of empyema. There was no significant difference in complication rate, mortality, and postoperative hospital stay.

Conclusions

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be accomplished safely in most patients with acute cholecystitis. The timing of surgery has no clinical relevant effect on conversion rates, operative times, morbidity, and postoperative hospital stay.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has become a treatment of choice for symptomatic gallstones or chronic cholecystitis. During the first years in the development of LC, acute cholecystitis (AC) has been considered to be a contraindication for performing this procedure. According to many authors, LC for AC may be technically difficult, related with complication, a high risk of accidental injuries of common bile duct, perforation of gallbladder, and gallstones spillage, etc. As more experience was obtained, AC then became a relative contraindication for LC and has been widely accepted as an effective treatment of AC. The aim of this study is to present our experience and results with performing LC for AC evaluating the effect of timing of surgery and the influence of the various types of gallbladder inflammation on patient outcome.

Materials and methods

Selection of patients and treatment

From August 1993 to December 2006 in the University hospital, Thracian University, Bulgaria, a retrospective study was performed on 255 patients who underwent LC for AC. The diagnosis of all of them was based on clinical signs and symptoms of AC. The clinical findings included abdominal tenderness in a right upper quadrant, fever, and leukocytosis. Patients were consequently excluded from the study if they had: (1) medical history and clinical, ultrasound, and laboratory data of extrahepatic cholestasis; (2) previous upper abdominal surgery; (3) simultaneous acute pancreatitis; (4) evidence of spreading peritonitis. The diagnosis was supported by dynamic ultrasonography and was confirmed by intraoperative finding and histological verification. The initial management of the patients was with second-generation cephalosporins and metronidazole. Intravenous fluid infusion was administrated to correct the volume and electrolyte deficits as well as analgesics. The patients were separated in three groups according to the time between the onset of symptoms and the operation: the “early” group was defined as LC completed in the first 72 h after the onset of the symptoms, the “intermediate” group from 4 to 7 days, and the “delayed” group with symptoms lasting more than 8 days. The decision to operate “early,” “intermediate,” or “delayed” was depended from such factors as a timing from the onset of symptoms to hospital admission, clinical and laboratory data, ultrasound examination (wall thickness of the gallbladder of more than 6 mm with or without a perigallbladder fluid collection), and white blood cell count of more than 15,000. Early cholecystectomy was indicated for patients with mild or moderate acute cholecystitis. In some patients with moderate cholecystitis, continuous medical treatment with “intermediate” or “delayed” cholecystectomy was the optimal treatment. Urgent management of severe acute cholecystitis was always necessary because of organ failure. More than 48–72 h of stabilization before surgery were required for the patients with associated acute medical problems (cardiac failure, acute renal failure, metabolic problems). Urgent or “early” cholecystectomy was required after improvement of patient’s general condition. The LC was usually completed within 72 h of admission. All data including demographic, preoperative, operative finding, postoperative complications were registered in computerized database.

Operative technique

The standard four-trocar technique was usually used. An additional fifth trocar was introduced in difficult cases. In case of suspicion of peritoneal adhesions, we used open technique for introducing the first trocar. For decompression of the gallbladders, all of them were punctured and the liquid content was partially aspirated. When the accidental laceration of gallbladder wall was extensive, the gallstones were collected in the specimen bag and removed from the peritoneal cavity along with the infected gallbladder. When the gallbladder wall was significantly thickened, instead of grasper we used a “crocodile” instrument for a good hold on the gallbladder. To avoid the hazardous procedure, subtotal laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SLC) was performed. The indications for SLC were severe inflammation, dense adhesions, difficulty in identifying and dissecting the structures in triangle of Calot. In case of stone impaction, the gallbladder was incised at the level of Hartmann’s pouch; the stone was extracted, then we tried to find the pathway of the cystic duct, to identify cystic duct and clipped. When this was impossible, the neck of the gallbladder was sutured or ligatured using an Endoloop. The intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) was completed only selectively. Often, the umbilical wound had to be extended for the extraction of the gallbladder when its wall is considerably thickened. Two closed suction silicon drains were used in all patients, placed in the subhepatic space. These were removed in most patients on the second or third day.

Statistical analysis

To establish the statistical significance of the observed differences, the Chi-square test with Yates’ correction, and the Mann–Whitney U test were used. All continuous data were expressed as median (range). For all statistical tests, P < 0.05 was considered to indicate significance.

Results

Two hundred fifty-five patients with clinical data, intraoperative finding, and histologically verified diagnosis of acute cholecystitis underwent LC. One hundred ninety-four (76%) of them were women and 61 (24%) men and the age ranged from 18 to 86. There were 115 (45%) patients who underwent “early” surgery; 70 (27.5%) patients had “intermediate’ surgery and 70 (27.5%) patients had “delay” surgery. The presence of associated diseases (cardiovascular, hypertension, diabetes, morbid obesity, renal, pulmonary problems, cirrhosis, previous surgery in lower abdomen, etc.) was observed in 66.6% of the patients. The demographic and clinical data were comparable between the three groups (Table 1).

The conversion rate in the “early” group was 14 patients (12.2%), in the “intermediate” group eight patients (11.4%), and in the “delay” group ten patients (14.3%).The total number of converted cases was 32 (12.5%). The reasons for conversion were unclear anatomy (19 patients), difficulty in dissection at the Calot’s triangle because of Mirizzi syndrome (four patients), uncontrolled bleeding (four patients), cholecystoenteric fistula (two patients), cancer of gallbladder (two patients), and bile duct injury (one patient). The analysis of evaluated parameters is exposed in Table 2. Although the conversion rate was higher in the “delay” group, this difference was not significant as regards the “early” group (P = 0.650) and “intermediate” group (P = 0.800)—Chi-square test with Yates’ correction. There was no significant difference in complication rate, mortality, and postoperative hospital stay. The significant differences of the conversion were observed according to the grade of severity of inflammatory changes of the gallbladder. There were 124 (48.6%) cases of AC, 53 (20.8%) cases of gangrenous cholecystitis, 27 (10.6%) cases of hydrops of gallbladder, and 51 (20%) cases of empyema. The conversion rate for patients with mild or moderate grade of acute cholecystitis was 6.4% and for hydrops of the gallbladder 7.4%. The conversion rate was considerably higher than that of acute cholecystitis for patients with gangrenous cholecystitis (22%, P = 0.002) and empyema of the gallbladder (19.6%, P = 0.009). This difference is considered to be very statistically significant (Table 3).

Based on operative findings, selective IOC was performed in 12 (4, 7%) patients because of suspicion of bile duct stones. Only with five of them (2%) were ductal stones detected. Laparoscopic stone clearance of the bile duct using flexible transcystic choledochoscop was successful in four of the patients and one underwent successful endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with stones extraction postoperatively.

Taking the experience and the advantage of performing subtotal open cholecystectomy and to avoid the risk of bile duct injury, we applied subtotal procedure in LC in eight patients with empyema of the gallbladder (3.1%). The reasons for it were unclear anatomy in Calot’s triangle, presence of severe inflammation, and predominant fibrosis in the region of the gallbladder’s neck and the cystic duct. Six of them were from the “delay” group and two patients from the “early” group.

The average length of the LC for each group depended on advanced changes in the gallbladder. The operating time in “early” group was 95 min (range, 50–180), 103 min (50–180) in “intermediate” group, and 120 min (50–180) for “delay” group. The difference of length of operative time between the three groups is statistically not significant (P > 0.05).

We have never hesitated to convert to open procedure in “difficult” cases to prevent severe complications. Median length of time for taking this decision was 15 (10–20) min.

Similarly, there was no significant difference in the mortality, morbidity, and postoperative hospital stay between the three investigated groups. There was no operative mortality or postoperative deaths. The overall complication rate in “early” group was 6.1%, in the “intermediate” 4.3%, and in the “delayed” group 11.4%. The complication rate in the converted group was 6.2%. Most of them were minor wound infections. We observed one major intraoperative complication. The common bile duct of one patient with empyema and Mirizzi syndrome was mistakenly transected as the cystic duct. The injury was discovered at the time of operation. Hepaticojejunostomy of a Roux-en-Y was performed and she recovered uneventfully. The patient was discharged in good condition and followed up to 10 years. There was one case of bile leakage from the drainages and signs of peritonitis. The complication was recognized on time and laparotomy was performed. The laparotomy revealed slipped clips by the cystic duct. There were not any clinical and laboratory data for cholestasis. One patient had undetected common bile stones manifested with postoperative transitory jaundice which required an extraction of the bile duct stones by ERCP and sphincterotomy. The average postoperative hospital stay was from 2 to 3 days and statistically relevant difference between the three groups regarding this parameter was not found.

Discussion

In the beginning, AC was considered a contraindication to LC. As a result of surgeons’ growing experience and skills, during the recent years, laparoscopic surgery has been approved to be a feasible and safe procedure for some simple forms of gallbladder inflammation. The controversial question has remained for an acutely inflamed and complicated gallbladder and the timing of surgery. The application of the laparoscopic approach in these cases is not well defined.

According to many authors, the timing of LC from the onset of symptoms to LC is an important factor determining the outcome for patients—the conversion rate, the operating time, the complications, and the hospital stay. The degree of histological changes and severity of the inflammation of gallbladder’s wall are proportional to the duration from the onset of the symptoms to the operation. It is clear that the more severe inflammatory changes occurred, the more difficult the performance of LC is. The pathological changes of the gallbladder’s wall are lower or moderate during the edema phase of acute inflammation and the performance of LC is an ordinary, easy, and feasible procedure as opposed to the later phase of inflammation when necrosis, hypervascularity, dense adhesions, and abscess formation occurred. The results of multiple randomized trials comparing early LC with delayed LC proved that performing the early surgery was superior to delayed interval surgery rate in terms of a lower conversion and complication and shorter hospital stay. Hence, the preferences and the recommendations of many authors are that the LC should be completed in the “early” phase of the disease [1–4]. Garber et al. [5] advocated early laparoscopic cholecystectomy within 4 days of the onset of symptoms to decrease major complications and conversion rates. Pessaux et al. [6] were of the same mind—LC should be carried out earlier than 3 days following the onset of the symptoms. In Table 4, we present the literature reports and results of the present study of conversion rate according to timing of LC for AC.

However, with the increasing experience, several trials have shown that in spite of the technical difficulties, LC can be safely performed, without complications in the “delayed” phase of the disease. Soffer and coauthors have accomplished 1,967 LC for AC with conversion rate of 14%. They did not find clinically relevant differences regarding conversion rates, operative time, or postoperative length of stay between patients who were operated on within 48 h compared to those patients who were operated on postadmission, days 3–7 [7]. Lau and co-workers, using metaanalytical techniques, evaluated four clinical trials comprising 504 patients. They did not establish any significant differences between the early and delayed LC for AC in terms of conversion, complication rates and operating time [8]. According to Wang et al. [9] the timing of urgent LC for AC has no impact on the conversion rate.

Our study confirmed that LC can be performed safely in most patients with AC. There was no mortality, with low percentage of conversion and complications. The results showed there was no significant difference in conversion rate and postoperative complications between the three investigated groups. The conversion rate in the “delay” group (14.3%) was not significantly higher than the “early” (12.2%) and “intermediate” (11.4%) groups.

We observed significant differences of the conversion rate according to the degree of severity of the inflammatory changes of the gallbladder. Different forms of AC carry various conversion and complication rates. Unlike simple forms of AC, which is associated with reasonable conversion rate of 6.4%, hydrops (7.4%) was considerably higher for patients with gangrenous cholecystitis (22%) and empyema (19.6%). These results are similar to the investigations of other authors. Elder and co-workers [10] reported a conversion rate for uncomplicated AC (8%), for gangrenous cholecystitis (40%), and for empyema of gallbladder (12.5%). Singer and Mckeen [11] reported a conversion to open cholecystectomy of 13.6% for AC and 75% for gangrenous cholecystitis. The literature reports regarding the conversion rate in LC at different stages of gallbladder disease is shown on Table 5.

The majority of patients in all three groups have had multiple previous episodes of biliary attacks and past history of biliary disease from 1 to 12 years. The consequence of each of them is a formation of dense chronic adhesions, especially in the region of Calot’s triangle, which make the blunt dissection difficult and unsafe. These changes influence the conversion and complication rates to a great degree.

We agree with Hashizume and MacFadyen [12] who “do not consider that conversion to open cholecystectomy should be viewed as a complication or as an operative failure. Rather, it should be seen as representing good surgical judgment.” We believe that a low threshold for conversion is important to minimize the risk of major complications.

Lo et al. [13] advocated an early decision for conversion of LC to open procedure for the treatment of AC. We consider that the surgeon should never hesitate to convert, should make an early decision for it within 15 to 20 min on average, and not persist with a difficult dissection.

LC is a technically feasible procedure for the majority of patients with some simple forms of AC. In their daily practice, the surgeons face difficult gallbladders with severe inflammation and fibrosis in Calot’s triangle with an increased risk of bile duct injury. The preferable procedure in these cases is the subtotal laparoscopic cholecystectomy [14]. We were forced to apply this procedure in eight patients with good postoperative results.

We did not find significant differences of complication rate in the three groups. The complication rate in the converted group was similar to the others. There was one major bile duct injury in the “delay” group with empyema of the gallbladder—transaction of common hepatic duct (grade 3, Bismuth classification). The cause of injury was an unclear anatomy of Calot’s triangle by severe adhesions and a combination of Mirizzi syndrome type I and slim common bile duct. It should be noticed that this injury happened during the initial experience of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. It was recognized at the time of LC. The primary repair with en-Roux-Y hepaticojejunostomy was done. Although C-N Yeh et al. [15] found the laparoscopic treatment for Mirizzi syndrome a “feasible and safe procedure,” we considered Mirizzi syndrome as a contraindication for LC in cases of AC.

There was no significant difference in the postoperative hospital stay. The median hospital stay in each of the evaluated groups was 2 or 3 days, except the converted group, where the average hospital stay was significantly longer—7 days.

Conclusion

LC can be accomplished safely in most patients with AC. The selection of cases suitable for LC should be based mainly on the experience and skills of surgeon. The acceptable conversion and complication rate would be achieved only in the hands of experts of laparoscopic techniques. In order to prevent severe complications, surgeons should never hesitate to convert to open cholecystectomy on time when anatomy of Calot’s triangle is unclear or the procedure is hazardous. But the decision of conversion should be taken on time, prior to the occurrence of complications. In fact, our results showed that performing the LC early was superior in terms of a lower conversion rate and a shorter operating time. These findings also refer to delayed surgery. The difference regarding these parameters is not significant.

LC for AC remains unpopular because of a lack of experienced surgeons, greater efforts for performing the procedure, and longer operative time. The LC for AC is safe when the indications and contraindications for LC were strictly observed. Otherwise, the excellent results of application of LC for AC would be obscured

Abbreviations

- LC:

-

laparoscopic cholecystectomy

- AC:

-

acute cholecystitis

- CBD:

-

common bile duct

- ERCP:

-

endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- IOC:

-

intraoperative cholangiography

- SLC:

-

subtotal laparoscopic cholecystectomy

References

Lo C-M, Fan S-T, Wong J (1998) Prospective randomized study of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg 227(4):461–467 April

Tzovaras G, Zacharoulis D, Liakou P, Theodoropoulos T, Paroutoglou G, Hatzitheofilou C (2006) Timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a prospective non randomized study. World J Gastroenterol 12(34):5528–5531 Sept 14

Koo KP, Thirlby RC (1996) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis. What is the optimal timing for operation? Arch Surg 131:540–546 May

Lai RBS, Kwong KH, Leung KL, Kwok SPY, Chan ACW, Chung SCS, Lau WY (1998) Randomized trial of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J of Surg 85:764–767

Garber SM, Korman J, Cosgrove JM, Cohen JR (1997) Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Surg Endosc 11(4):347–350 Apr

Pessaux P, Tuech JJ, Rouge C, Duplessis R, Cervi C, Arnaud JP (2000) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis. A prospective comparative study in patients with acute vs chronic cholecystitis. Surg Endosc 14(4):358–361 Apr

Soffer D, Blackbourne LH, Schulman CI, Goldman M, Habib F, Benjamin R et al (2007) Is there an optimal time for laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis? Surg Endosc 21:805–809 Dec

Lau H, Lo CY, Patyl NG, Yuen WK (2006) Early versus delayed-interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a metaanalysis. Surg Endosc 20(1):82–87 Jan

Wang YC, Yang HR, Chung PK, Jeng LB, Chen RJ (2006) Urgent laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the management of acute cholecystitis: timing does not influence conversion rate. Surg Endosc 20(5):806–808 May

Eldar S, Sabo E, Nash E, Abrahamson J, Matter I (1998) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for various types of gallbladder inflammation. A prospective trial. Surg Laparosc Endosc 8(3):200–207

Singer JA, Mckeen RV (1994) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute or gangrenous cholecystitis. Am Surgeon 60:326–328 May

Hashizume M, MacFadyen BV (1998) The clinical management and results of surgery for acute cholecystitis. Semin Laparosc Surg 5(2):69–80 June

Lo C-M, Fan S-T, Liu C-L, Lai ECS, Wong J (1997) Early decision for conversion of laparoscopic to open cholecystectomy for treatment of acute cholecystitis. Am J Surg 173:513–517 Jun

Michalowski K, Bornman PC, Krige JEJ, Gallagher PJ, Terblanche J (1998) Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy in patients with complicated acute cholecystitis or fibrosis. Br J Surg 85:904–906

Yeh C-N, Jan Y-Y, Chen M-F (2003) Laparoscopic treatment for Mirizzi syndrome. Surg Endosc 17:1573–1578

Kum Ch-K, Eypasch E, Lefering R, Paul A, Neugebauer E, Troidl H (1996) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: is really safe? World J Surg 20:43–49

Cox MR, Wilson TG, Luck AJ, Jeans PL, Padbury RTA, Toouli J (1993) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute inflammation of the gallbladder. Ann Surg 218(5):630–634

Bingener J, Stefanidis D, Richards ML, Schwesinger WH, Sirinek KR (2005) Early conversion for gangrenous cholecystitis: impact on outcome. Surg Endosc 19(8):1139–1141 Aug

Habib FA, Kolachalam RB, Khilnani R, Preventza O, Mittal VK (2001) Role of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the management of gangrenous cholecystitis. Am J Surg 181(1):71–75 Jan

Suter M, Meyer A (2001) A 10-year experience with the use of laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: is it safe? Surg Endosc 15(10):1187–1192 Oct

Tsushimi T, Matsui N, Takemoto Y, Kurazumi H, Oka K, Seyama A, Morita T (2007) Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute gangrenous cholecystitis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 17(1):14–18 Feb

Araujo-Teixeira JP, Rocha-Reis J, Costa-Cabral A, Barros H, Saraiva AC, Araujo-Teixeira AM (1999) Laparoscopy or laparotomy in acute cholecystitis (200 cases). Comparison of the results and factors predictive of conversion. Chirurgie 124(5):529–535 Nov

Koperna Th, Kisser M, Schulz F (1999) Laparoscopic versus open treatment of patients with acute cholecystitis. Hepato-Gastroenterology 46:753–757

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Popkharitov, A.I. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Langenbecks Arch Surg 393, 935–941 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-008-0313-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-008-0313-7