Abstract

Background

Dialysis shunt-associated steal syndrome (DASS) is a rare complication of hemodialysis access (HA) which preferably occurs in brachial fistulas. Treatment options are discussed controversially. Aim of this study was to evaluate flow-controlled fistula banding.

Materials and methods

Patients treated between 2002 and 2006 were included in this prospective survey. According to a classification we established, patients were typed DASS I–III (I: short history, no dermal lesions; II: long history, skin lesions; III: long history, gangrene). Surgical therapy was HA banding including controlled reduction (about 50% of initial flow) of HA blood flow (patients type I and II). Patients with type III underwent closure of the HA.

Results

In 15 patients with relevant DASS, blood-flow-controlled banding was performed. In ten patients (all type I), banding led to restitution of the hand function while preserving the HA. In five patients (all type II), banding was not successful; in two patients, closure of the HA was performed eventually. In five patients (type III), primary closure of the HA was performed. Four patients with DASS type II but only two with DASS type I had diabetes mellitus (p = 0.006).

Conclusions

Banding under blood flow control resulting in an approximately 50% reduction in the initial blood flow is an adequate therapeutic option in patients with brachial HA and type I-DASS. In type II-DASS, banding does not lead to satisfying results, more complex surgical options might be more successful. Diabetes is associated with poor HA outcome in case of DASS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A sufficient vascular access is a premise for long time hemodialysis. Because of its easy performance and little complication rates, hemodialysis accesses (HA) according to Cimino–Breschia are commonly used as first HA of choice [1, 2]. In case of primary or secondary insufficiency, other HA are indicated [1]. A rare but important complication of HA is dialysis shunt-associated steal syndrome (DASS). “Steal phenomenon” is the result of a change of hemodynamic flow; the term “steal syndrome” is used in case of clinical symptoms [3]. The cause of DASS is multifactorial. Different forms and characteristics of DASS have been reported on; however, no general classification has been established yet. Because of the risk of severe damage of the extremity, DASS is a complication of high interdisciplinary clinical importance.

Accesses originating from the brachial artery are a major predisposing factor for ischemia [4, 5]. As main therapeutic options for DASS, distal revascularization interval ligation (DRIL procedure [6, 7]) and fistula banding or closure have been described. Especially the DRIL procedure we usually perform in case of DASS after radial fistulas. As a new technique the proximalization of the arterial inflow (PAI) [8] has been published recently. This technique, which needs to be further evaluated, includes implantation of prosthetic material and may be a good alternative in advanced DASS.

However, in case of brachial fistulas, where DRIL as best known technique is not the therapy of first choice (ligation of the patent brachial artery is a key element of the procedure), there is an ongoing debate regarding the best treatment options. Only few reports on HA-preserving therapy, including fistula banding, which at the same time is the least complex surgical intervention, have been published. Aim of this prospective study was to evaluate indication and technique of controlled blood flow reduction (banding) of the fistula vein in brachial fistulas by using a blood-flow-measuring instrument.

Materials and methods

In this prospective study, all patients with DASS after brachial HA that were treated in our institutions (University Hospital Halle and University Teaching Hospital St. Elisabeth Halle) were included. Period of time of the study was 2002–2006. The decision for surgical treatment was made interdisciplinary (angiologist, neurologist, surgeon). As the patients presented different forms of steal syndrome, we established a clinical classification including three types (Table 1). This classification was induced according to pathological changes of the distal limb and according to the time of onset of complaints. According to this classification, either HA-preserving surgery (type I, II) was performed or HA was closed directly (type III).

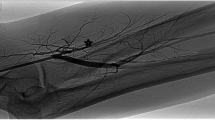

Before surgery, all patients underwent clinical examination (inspection, palpation of the shunt veins and arteries with and without venous congestion, shunt auscultation) as well as angiological examination (Doppler/Duplex, Fig. 1). In case of neurologic symptoms, specific examinations, including electromyography (Fig. 2), were performed by a neurologist. Surgery was performed under local or regional (plexus) anesthesia in all cases.

Preoperative (left, normal flow at congestion of the fistula vein directly behind the anastomosis) and postoperative (right, normal flow after banding) Doppler/Duplex scan of the radial artery. On the left figure, the arrow marks the release of congestion of the fistula vein with an immediate deterioration of the peripheral flow

Stimulation of the ulnar and the median nerve: total nerval functional loss (left, no nerval answer to stimulation) and regain of function after banding (right, nerval answer to stimulation). This figure is presented with the friendly permission of the Springer-Verlag and was published in the “Gefässchirurgie” [25]

As surgical therapy, fistula banding was performed. In case of failing improvement, reoperation was added. In three patients this meant closure of the fistula. In two patients, however, interposition of a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) loop resembling a technique described by Zanow et al. [8] and modified by Henriksson and Bergqvist [9] was performed. In case of fistula banding, aim was to put down the flow to approximately 50% (but never below 250 ml/min) of the initially measured flow. Therefore, a blood flow measurement (Medi-Stim®, Sandakerveien, Norway, Fig. 3), which enables direct and permanent blood flow measuring, was employed. As banding technique circular restriction combined with a longitudinal (non resorbable) suture (“tailoring”) was performed (Fig. 3). Postoperatively, all patients were reexamined angiologically (fistula flow and hand perfusion) and neurologically. The operation was accepted as successful if the hand function could be restored and the fistula be used for dialysis. As follow-up the patients were seen in our vascular outpatient clinic 3 months after surgery, followed by 6-month intervals. Statistical analysis (chi-square test) was done with SSPS; p value was considered significant if <0.05.

Results

Between 2002 and 2006, 737 HA were performed in our institution. In 20 patients a relevant DASS after brachial access and four after radial access (not included in this survey) developed (3.3% DASS in summary). Of the 20 patients, 15 (type I and II) were included in this study. Those patients belonging to group III (n = 5) were excluded from the survey as the fistulas were eventually closed in all cases because of severe gangrene of the limbs. In those patients the time of duration of complaints was more than 2 months (Table 2). Preoperatively, arterial function had been sufficient (adequate biphasic or triphasic flow pattern, no relevant arterial obstruction, patent radial and ulnar arteries) in all ten patients with type I as proved by Doppler/duplex and clinical examination; however, four of the five patients with type II had severe mediasclerosis. Among the 15 patients (seven men and eight women, age 46–84, median 70 years), there were 11 with cephalica, two with basilica, and two with prosthetic straight shunts of the upper arm. According to our classification, ten patients were staged type I and five type II as described above (one initially type I but turned into type II after unsuccessful conservative therapy) and five type III. Of the ten patients staged type I, three suffered from diabetes mellitus; from those staged type II, all but one had diabetes mellitus (Tables 2 and 3).

Of the 15 patients included in the survey in five cases, fistula banding did not lead to an improvement of the symptoms (one patient with dystrophy, four patients with ecrosis and pain at rest) and therefore had to undergo second operation (Table 2). In three cases, closure was performed; in two cases, the shunt could be preserved by interpositioning a PTFE loop. According to our classification, all five patients belonged to group II (one of them, however, initially was group I but not treated by fistula banding early enough). Postoperative specific reexamination of neurologists and angiologists showed a total restitution of the hand (full function) in four cases.

In ten patients the HA could be successfully preserved by fistula banding. All patients were type I-DASS. Duration of symptoms was short (<14 days); symptoms were coldness and numbness as well as severe stress-induced pain without dystrophic or atrophic changes. Five patients (6, 8, 9, 11, 13, Table 3) additionally had acute sensomotoric failure of the hand. In three patients, symptoms of DASS occurred several month after insertion of the HA (patients 6, 8, 9, Table 3); in all three cases, an aneurysm of the fistula vein with high flow was the reason for the acute symptoms of DASS. The other patients did not show any specific changes of the fistula vein.

Postoperative subject-specific reexamination of the 12 patients with preserved HA by neurologists and angiologists showed a sufficient arterial blood flow in all cases and normal neurologic functions in those cases with neurologic symptoms. Time of follow-up was 6–70 months (mean follow-up 18 months). In all but one (shunt had to be closed because of puncture-related infection after 2 months) cases, the HA could be used for dialysis. Three patients died (for cardial insufficiency in all cases) after 36, 50, and 70 months, respectively, with patent HA. The remaining eight patients still undergo hemodialysis via banded HA. No revision of the HA was necessary in the DASS type I group. Of the three patients with type II in two cases, revision was necessary after 18 and 24 month, respectively, for shunt thrombosis. Thirty-days patency was 100%, 1-year patency 91%, and 2-year patency 75% (secondary patency 91%).

Gender and age did not show any significant differences between the two patient groups (HA preserving vs HA closure; Tables 2 and 3). Statistical analysis (chi-square test) showed that underlying diabetes mellitus was significantly associated (p = 0.006) with the development of DASS types II and III (the latter group was excluded from surgical evaluation) and with the need for closure of the HA, respectively (p < 0.001).

Discussion

A sufficient access is a premise for long time dialysis. A rare but important complication of HA is DASS (2–10% [10, 11]). A dialysis access always means a change of the hemodynamic flow of the extremities, which usually does not lead to clinical symptoms [12]. Moderate ischemic symptoms can occur but mostly resolve spontaneously within several weeks [13]. According to our experience, only few patients suffer from minor problems such as intermittent coolness of the hand or weakness after exercise. In 15 (2%) own patients (data not presented), these symptoms resolved within a few weeks of conservative treatment. In rare cases, however, ischemia-associated complications with the need for surgical intervention may develop.

As far as we know to date, DASS cannot be predicted. Neither the patients’ medical history nor certain measuring methods or surgical techniques can satisfyingly minimize the risk of development of DASS [12, 14, 15].

Accesses originating from the brachial artery are a major predisposing factor for ischemia. The absence of collateral vessels around the elbow seems to be one of the reasons [4, 5]. According to our experience, too, DASS after brachial fistulas occurs more often than in radial fistulas. The development of a DASS seems to be multifactorial. Occlusive arterial disease, stenotic areas, underlying neuropathic diseases, or calcifying sclerosis have been described as risk factors for the development of DASS [3, 4]. Typical severe ischemic pain, either stress-induced or at rest, pallor or livid discoloration, necrosis, or gangrene are clear signs of DASS [14]. More difficult to evaluate are reversible or irreversible neurologic symptoms. In many cases, their pathogenesis remains unclear [11]. Carpal-tunnel-syndromes as well as dystrophy syndromes have been described [16, 17]. Another rare neurologic manifestation of DASS is the ischemic monomelic neuropathy (IMN), with assumably distal axonopathy in combination with diabetic polyneuropathy or peripheral arteriosclerosis as preconditions [11, 18, 19]. Neurologic as well as nonneurologic symptoms after DASS can occur acutely or after longer periods [11, 17]. Several therapeutic options preserving HA function in DASS have been described: Angioplasty [20] as nonoperating intervention and HA banding, DRIL (distal revascularization interval ligature) procedure [6, 7], RUDI (revision using distal inflow) procedure [21], and loop-interposition [8, 9] as operating techniques. However, because of little experience, procedures are mostly chosen individually and results are discussed controversially (Table 4). Although fistula banding is the easiest way of treating DASS, there are only few reports on the success of this technique. One reason is the inherent problem with balancing fistula flow with distal flow [22]. Especially the question, if in case of brachial-HA fistula banding can be performed with satisfying results, has not been answered yet, although procedures such as DRIL (ligation of a patent brachial artery) are not the therapy of first choice at this localization. No prospective study has been published on the intraoperative evaluation of flow reduction measurements, respectively. However, according to our results, fistula banding can lead to very good long-term results with the premise of correct indication. Therefore, we evaluated a classification of the different types of DASS. Accordingly, we found that, in case of type I-DASS, a successful fistula banding could be performed even in case of neurologic deficiency. Patients with long-durating symptoms, on the other hand, often showed damages such as dystrophic symptoms or necrosis (type II-DASS). Reasons for this development might be a deteriorated arterial inflow, e.g., due to mediasclerosis and a retrograde flow mechanism diminishing the blood flow to the forearm. Accordingly, in our survey, fistula banding was not successful in any of such cases and does not seem to be an adequate technique at this stage of disease. In two of five patients, we therefore added a technique that minimized the retrograde blood flow component by inserting a PTFE loop. If such a technique is generally successful in type II-DASS, it has not been evaluated yet [9, 21]. Undoubtedly, such an operation is more invasive, and allogene material has to be used. Type III-DASS (patients with extended tissue loss or gangrene) probably cannot be sufficiently therapied without sacrificing the HA. Accordingly, in order not to venture the limb, we closed the HA in such patients. If techniques such as DRIL can be a sufficient therapy in DASS type III, it is unknown because of missing experience. Some authors generally propagate closure of the HA in case of tissue loss (which would be types II and III according to our classification) [11]. In our patients, type II as well as type III were significantly associated with diabetes mellitus. This has been described by other authors, too [3]. According to our results, diabetes mellitus is an important factor for poor outcome regarding successful intervention in DASS. However, if patients with diabetes mellitus develop type I-DASS (as three of our patients) banding procedure as described should be performed.

As an interesting aspect in three patients, acute DASS occurred after a long period of normal fistula function; in all cases, the reason was an aneurysm of the fistula vein. Accordingly, pathological changes and not time of fistula insertion seem to be the important aspects for clinical evaluation (types I–III). Whether early treatment of type I-DASS by fistula banding can prevent the development of type II/type III-DASS or if different pathophysiological changes irrespective of time of duration lead to the different types of DASS is not clear yet and needs further investigation.

Conclusion

DASS is a rare but important complication of HA and mostly occurs in brachial HA. As far as we know, DASS cannot be predicted. The cause of DASS is multifactorial. Because of that there are different forms and characteristics of DASS with different ways of treatment. We evaluated a classification of three different types of DASS that we have established in our institution. We found that HA banding under blood flow control as easily performable procedure is an adequate therapeutic option in patients with brachial HA and type I-DASS. In type II-DASS, banding does not lead to satisfying results. In such cases, as in type III-DASS, more complex surgical options might lead to better results. Diabetes is associated with poor outcome in patients with DASS.

References

Burkhart HM, Cikrit DF (1997) Arteriovenous fistulae for hemodialysis. Semin Vasc Surg 10(3):162–165

Wehrli H, Chenevard R, Zaruba K (1989) Surgical experiences with the arteriovenous hemodialysis shunt (1970–1988). Helv Chir Acta 56(4):621–627

White JG, Kim A, Josephs LG (1999) The hemodynamics of steal syndrome and its treatment. Ann Vasc Surg 13:308–312

Miles AM (1999) Vascular steal syndrome and ischaemic monomelic neuropathy: Two variants of upper limb ischaemia after haemodialysis vascular access surgery. Nephrol Dial Transplant 14:297–300

Haisch CE, Cerilli J (1997) Vascular access procedures for renal dialysis. In: Textbook of surgery, 15th edn. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, pp 429–436

Korzets A, Kantarovsky A, Lehmann J, Sachs D, Gershkovitz R, Hasdan G, Vits M, Portnoy I (2003). The “DRIL” procedure—a neglected way to treat the steal syndrome of the hemodialysed patient. Israel Med Assoc J 5(11):782–785

Jean-Baptiste RS, Gahtan V (2004) Distal revascularization-interval ligation (DRIL) procedure for ischemic steal syndrome after arteriovenous fistula placement. Surg Technol Int 12:201–205

Zanow J, Kruger U, Scholz H (2006) Proximalization of the arterial inflow: a new technique to treat access-related ischemia. J Vasc Surg 43(6):1216–1221

Henriksson AE, Bergqvist D (2005) Steal syndrome after brachiocephalic fistula for vascular access: Correction with a new simple surgical technique. J Vasc Access 5:13–15

Isoda S, Kajiwara H, Kondo J, Matsumoto A (1994) Banding a hemodialysis arteriovenous fistula to decrease blood flow and resolve high output cardiac failure: report of a case. Surg Today 24(8):734–736

Unek IT, Birklik M, Cavdar C (2005) Reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome due to arteriovenous fistula. Hemodial Int 9:344–348

Kwun KB, Schanzer H, Finkler N, Haimov M, Burrows L (1979) Hemodynamic evaluation of angioaccess procedures of hemodialysis. Vasc Surg 13:170–177

Valji K, Hye RJ, Roberts AC (1995) Hand ischemia in patients with hemodialysis access grafts. Angiographic diagnosis and treatment. Radiology 196:697–701

Aschwanden M, Hess P, Labs KH, Dickenmann M, Jaeger K (2003) Dialysis access-associated steal syndrome: The intraoperative use of duplex ultrasound scan. J Vasc Surg 37(1):211–213

Lazarides MK, Staramos DN, Panagopoulos GN (1998) Indications for surgical treatment of angioaccess induced arterial “steal”. J Am Coll Surg 187(4):422–426

Martinelli P, Baruzzi A, Montagna P (1981) Carpal tunnel syndrome in a patient with a cimino–brescia fistula. Eur Neurol 20(6):478–480

Harding AE, Le Fanu J (1977) Carpal tunnel syndrome related to antebrachial cimino–brescia fistula. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 40(5):511–513

Weinberg DH, Simovic D, Isner J (2001) Chronic ischemic monomelic neuropathy from critical limb ischemia. Neurology 57(6):1008–1012

Hye RJ, Wolf YG (1994) Ischemic monomelic neuropathy: an underrecognized complication of hemodialysis access. Ann Vasc Surg 8(6):578–582

Asif A, Leon C, Merrill D, Bhimani B, Ellis R, Ladino M, Gadalean FN (2006) Arterial steal syndrome: a modest proposal for an old paradigm. Am J Kidney Dis 48(1):88–97

Minion DJ, Moore E, Endean E (2005) Revision using distal inflow: a novel approach to dialysis-associated steal syndrome. Ann Vasc Surg 19:625–628

Goel N, Miller GA, Jotwani MC, Licht J, Schur I, Arnold WP (2006) Minimally Invasive Limited Ligation Endoluminal-assisted Revision (MILLER) for treatment of dialysis access-associated steal syndrome. Kidney Int 70(4):765–770

Morsy AH, Kulbasdi M, Chen C, Isiklar H, Lumsden AB (1998) Incidence and characteristics of patients with hand ischemia after a hemodialysis access procedure. J Surg Res 74(1):8–10

Odland M, Kelly PH, Ney AL, Andersen RC, Bubrick MP (1991) Management of dialysis-associated steal syndrome complicating upper extremity arteriovenous fistulas: use of intraoperative digital photoplethysmography. Surgery 110(4):664–669

Thermann F, Kornhuber M, Brauckhoff M (2006) Dialysis associated steal syndrome—can the access be preserved? Gefässchirurgie 11:360–363 (copyright by the Springer Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thermann, F., Ukkat, J., Wollert, U. et al. Dialysis shunt-associated steal syndrome (DASS) following brachial accesses: the value of fistula banding under blood flow control. Langenbecks Arch Surg 392, 731–737 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-007-0207-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-007-0207-0