Abstract

Background and aims

We report on our series of patients selected for video-assisted thyroidectomy (VAT) over a 7-year period.

Materials and methods

VAT is a gasless procedure performed under endoscopic vision through a single 1×5×2.0-cm skin incision. The eligibility criteria are thyroid nodules ≤35 mm, thyroid volume <30 ml, and no previous conventional neck surgery. Small, low-risk papillary thyroid carcinomas (PTC) were considered eligible.

Results

There were 521 VATs attempted. Conversion was necessary six times (difficult dissection in one case, large nodule size in three, and gross lymph node metastases in two). Thyroid lobectomy was successfully accomplished in 113 cases, total thyroidectomy in 398, and completion thyroidectomy in 14. In 66 patients, the central neck nodes were removed through the same access. Pathology showed benign diseases in 313 cases, PTC in 187, and medullary microcarcinoma in 1. Postoperative complications included 9 transient recurrent nerve palsies, 73 transient hypocalcemias, 3 definitive hypoparathyroidisms, 1 postoperative haematoma, and 2 wound infections. The cosmetic result was excellent. In patients with PTC, no evidence of recurrent disease was shown.

Conclusions

The indications for VAT are still limited. Nonetheless, in selected patients, it seems a valid option for thyroidectomy and even preferable to conventional surgery because of its significant advantages, especially in terms of cosmetic result.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, several techniques for minimally invasive thyroidectomy have been described, with the primary aim to improve the cosmetic results of conventional surgery [1]. The different techniques include endoscopic and video-assisted procedures [2–6] and mini-access, non-endoscopic operations [7, 8].

Video-assisted thyroidectomy (VAT), which we adopted and described since 1998 [6], is a completely gasless procedure that reproduces in each step conventional surgery [6, 9]. The approach is similar to what P. Miccoli described for parathyroidectomy and successively adopted also for thyroidectomy [10].

VAT has been already adopted by several centers, especially in Europe [6, 9–11]. Relatively small comparative studies demonstrated that it can obtain the same results with that of conventional surgery with some significant advantages in terms of cosmetic result and postoperative pain [12–14]. Larger multi-institutional series gave a further demonstration of its efficacy and safety [11]. VAT showed results comparable to those of conventional surgery in terms of the completeness of the surgical resection [15, 16] and no additional risk of cancerous cells seeding [14] in the treatment of small, low-risk papillary thyroid carcinomas (PTC). Moreover, we have recently demonstrated that VAT is feasible also under loco-regional anesthesia [17]. These characteristics rendered it, in less than one decade, a valid and, in selected cases, even a preferable option for the surgical treatment of thyroid diseases.

In this study, we report on the entire series of patients who underwent VAT at our department over a 7-year period.

Materials and methods

Among the 3,165 patients who underwent thyroid operations from June 1998 to June 2005, we selected for VAT 507 patients (441 women and 66 men) with a mean age of 43.7±13.6 years (range 10–78). At the beginning of the experience, the eligibility criteria were: thyroid nodules ≤35 mm and estimated thyroid volume within the normal range (<20 ml); no previous neck surgery and/or radiation therapy; and no thyroiditis. After an initial learning period, previous video-assisted thyroid lobectomy and thyroiditis were still not considered a contraindication for VAT. Patients with Graves’ disease (preoperatively estimated thyroid volume <30 ml), small (T1–small T2), low-risk [18] PTC or RET germline mutation carriers were considered potential candidates for VAT. Concomitant parathyroid adenomas can be removed by the same approach. Absolute contraindications are represented by malignancies other than “low-risk papillary carcinoma” and the presence of preoperatively demonstrated lymph node involvement/metastases. On the other hand, in case of PTC or suspicious nodules, if unexpectedly enlarged lymph nodes are identified in the central compartment, they can be dissected and removed by the same video-assisted procedure (VALD, video-assisted lymph node dissection) [16, 19].

All of the patients gave their informed consent. The operative technique has been already described elsewhere [9]. The procedure is usually performed under general anesthesia, but it can be performed also under loco-regional anesthesia (modified superficial cervical block) [17].

The patient is placed in a supine position, with slight extension in the neck. A 15- to 20-mm skin incision is performed between the sternal notch and the cricoid cartilage, in the midline. The cervical linea alba is then opened, as far as possible. The thyroid lobe is carefully dissected from the strap muscles. Operative space is maintained by small conventional retractors, which are used to medially retract the thyroid and to laterally retract the strap muscles. The endoscope (5-mm, 30°) and the surgical instruments are inserted through the single skin incision, without any trocar insertion. Small (2–3 mm in diameter) conventional forceps and special instruments derived from ENT and plastic surgery (forceps, scissors, spatulas, and spatula-shaped aspirator) are used for dissection. For hemostasis, we use small (3 mm in diameter) conventional clips or the 5-mm, 14 cm in length Harmonic Scalpel (HS) scissors (Ethicon ENDO-SURGERY, Cincinnati, OH 45242-2839, USA). After sectioning the middle thyroid vein, the thyroid lobe is retracted downward to expose the vessels of the upper pole and, in most of the procedures, the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve is identified. After sectioning the vessels of the superior pole, the traction over the lobe is oriented medially so as to expose the tracheo-esophageal groove. The recurrent laryngeal nerve is usually identified where it crosses the inferior thyroid artery and then dissected away from the thyroid lobe under endoscopic vision as well as from the parathyroid glands. After removing the retractors, the thyroid lobe is extracted through the skin incision, taking care to avoid any rupture. The dissection of the lobe is then completed under direct vision. In case of total thyroidectomy, the procedure is completed on the opposite side. In case of malignant or suspicious nodules, if unexpectedly enlarged lymph nodes are identified in the central compartment, a VALD is performed.

Results

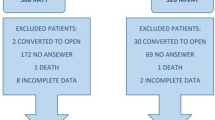

Five hundred twenty-one VAT procedures were attempted in 507 patients. The pre-operative diagnoses were euthyroid multinodular goiter in 92 (18.2%) cases, toxic multinodular goiter in 35 (6.9%), toxic adenoma in 26 (5.1%), Graves’ disease in 12 (2.4%), follicular (indeterminate) nodule in 143 (28.2%), suspicious nodule in 144 (28.4%), low-risk PTC in 54 (10.6%), and RET mutation in 1 (0.2%). The mean maximum diameter of the nodules was 21.2±9.5 mm (range 6–45 mm). Mean thyroid gland weight was 24.1±15.9 g (range 4–70).

A loco-regional anesthesia (VAT-AL) was performed in 15 cases (five lobectomy and ten total thyroidectomy, 3.0%).

The procedure was successfully carried out in 515 cases (98.8%): 113 lobectomies, 398 total thyroidectomies, and 14 completion thyroidectomies. The conversion to conventional procedure was necessary six times (1.1%) because of difficult dissection in one case, large nodule size which had been underestimated by preoperative ultrasonography in three cases, and intra-operative finding of gross central neck and upper mediastinum lymph node metastases in the remaining two.

A VALD was performed in 75 patients with thyroid carcinoma: in 63 of them with preoperative diagnosis of small, low-risk PTC or suspicious nodules, only the enlarged central neck nodes were removed; in the remaining 12 (11 with PTC and 1 with germline RET mutation), a complete central compartment lymph node dissection was carried out (VALD). The mean number of lymph node removed during central compartment dissection (CCD) was 7.6±1.2 (range 6–12). Concomitant parathyroidectomy for a parathyroid adenoma was performed in 16 patients.

The mean operative time was 59±21 min (range 20–150) for thyroid lobectomy, 65±15 (range 35–220) for total thyroidectomy, and 51±20 (range 30–100) for completion thyroidectomy.

Among the patients who successfully underwent VAT, final histology showed benign diseases in 313 cases, PTC in 187, and medullary microcarcinoma in 1 with germline RET mutation. Lymph node metastases of PTC were found in 16 patients.

Postoperative complications included 9 transient recurrent nerve palsies (1% of the nerves at risk), with complete recovery of nerve function within 1 month after surgery; 73 transient hypocalcemias (17.7%) (which required calcium and vitamin D administration for less than 6 months); 3 definitive hypocalcemias (0.7%) (which required administration of calcium and vitamin D for more than 6 months postoperatively); 1 postoperative haematoma (0.2%) requiring re-operation; and 2 wound infections (0.4%). Mean postoperative stay was 2.6+1.2 days. The cosmetic results were considered excellent by most of the patients.

Among patients with PTC, follow-up has been completed in 141 (74.2%). In 63 (44.7%) pT1 low-risk patients, sTg on LT4 was undetectable (<0.1 ng/ml) and an ultrasound neck scan showed no thyroid remnant or lymph node involvement. In the remaining 78, mean sTg on LT4 was 0.1 ng/ml (range <0.1–0.6) and sTg off LT4 6.5±6.4 ng/ml (range <0.1–22.4); neck ultrasonography showed no thyroid remnant or lymph node involvement, mean 24-h RAIU was 2.6±4.1% (range 0–22.6%). Anyway, RAI uptake was absent in 11 patients (14.1%) and <2% in 48 (61.5%). The patient with germline RET mutation and medullary microcarcinoma showed undetectable basal and stimulated CT.

Discussion

During the last decade, there was a strong impulse towards the development of minimally invasive techniques for thyroidectomy, and several procedures have been described [1]. Although it is not possible to argue which is the best technique, it is quite clear that VAT encountered most favors. It has been adopted by different surgical teams, and quite a number of large series, also multi-institutional, have been published [6, 9–14].

The application of minimally invasive techniques for thyroid surgery was mainly determined by the attempt to improve the cosmetic result of this operation. Despite no advantages should be expected from VAT in terms of surgical stress, previously published papers demonstrated that it has some advantages over conventional operations not only in terms of cosmetic result but also of analgesic requirements and postoperative recovery with a similar complication rate [12–14].

The present data, based on a quite large series of patients, confirm that VAT is characterized by a complication rate not higher than that of conventional surgery and by an excellent cosmetic result.

In spite of these results, the introduction of VAT encountered several skepticism, which are focused mainly on its role in the treatment of thyroid malignancy and its real clinical impact. However, in a previously published comparative study, we have already demonstrated that thyroid gland manipulation is not substantially different in VAT and conventional surgery and that there is no additional risk of thyroid capsule rupture and thyroid cells seeding in patients who undergo VAT [14]. Furthermore, the results obtained in terms of the completeness of surgery (as evaluated by postoperative sTg on and off LT4, ultrasound scan, and radioiodine uptake) are similar to those of conventional surgery [15, 16]. These results convinced us to currently propose VAT for small, low-risk PTC in absence of overt lymph node involvement at preoperative work-up. On the other hand, the radicalness of the surgical resection should be regarded also as a possibility to perform a central neck node clearance, when indicated. The results of this study also confirm that removal of enlarged central neck nodes and CCD is feasible, with no additional morbidity. Obviously, conversion is mandatory if the node clearance cannot be as accurate as in conventional surgery. Nonetheless, we still consider that preoperatively demonstrated overt lymph node involvement is an absolute contraindication for video-assisted procedures.

Some have argued that VAT and all minimally invasive procedures are characterized by higher costs when compared with conventional surgery because of longer operative time and special instrumentation. However, it has been already demonstrated that, after a learning period, operative time is similar to that of conventional operations [6, 9–14]. Moreover, all the instruments are re-useable with the exception of HS. Indeed, HS is disposable and could be considered as an additional cost, but it is not peculiar of minimally invasive surgery. Its use is proposed more and more frequently also in conventional surgery because, in several experiences, it has been demonstrated that it allows for a significant reduction of the operative time [20]. In other words, after a learning period, the overall costs for VAT are similar to those of conventional surgery.

Thus, the main limit of VAT probably still remain the relatively small number of patients who fulfil the selection criteria. Undoubtedly, this could reduce the clinical impact of the procedure. However, in our experience, at present, more than 20% of the patients who require for a thyroidectomy are potential candidates for VAT. Despite that they still represent a minority of the patients we operated on, this percentage is not negligible.

As VAT has demonstrated significant advantages over conventional surgery, with no additional morbidity, we think that this option should be offered to patients who undergo thyroidectomy, at least in selected referral centers, and it should be included in the armamentarium of the modern endocrine surgeons.

References

Duh QY (2003) Presidential address: minimally invasive endocrine surgery—standard treatment of treatment or hype? Surgery 134:849–857

Gagner M, Inabnet WB (2001) Endoscopic thyroidectomy for solitary thyroid nodules. Thyroid 11:161–163

Shimizu K, Akira S, Jasmi AY, Kitamura Y, Kitagawa W, Akasu H, Tanaka S (1999) Video-assisted neck surgery: endoscopic resection of thyroid tumors with a very minimal neck wound. J Am Coll Surg 188:697–703

Ikeda Y, Takami H, Tajima G, Sasaki Y, Takayama J, Kurihara H, Niimi M (2002) Total endoscopic thyroidectomy: axillary or anterior chest approach. Biomed Pharmacother 56(Suppl 1):72s–78s

Ohgami M, Ishii S, Arisawa Y, Ohmori T, Noga K, Furukawa T, Kitajima M (2000) Scarless endoscopic thyroidectomy: breast approach for better cosmesis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 10:1–4

Bellantone R, Lombardi CP, Raffaelli M, Rubino F, Boscherini M, Perilli V (1999) Minimally invasive, totally gasless video-assisted thyroid lobectomy. Am J Surg 177:342–343

Ferzli GS, Sayad P, Abdo Z, Cacchione RN (2001) Minimally invasive, nonendoscopic thyroid surgery. J Am Coll Surg 192:665–668

Brunaud L, Zarnegar R, Wada N, Ituarte P, Clark OH, Duh QY (2003) Incision length for standard thyroidectomy and parathyroidectomy. When is it minimally invasive? Arch Surg 138:1140–1143

Bellantone R, Lombardi CP, Raffaelli M, Boscherini M, De Crea C, Traini E (2002) Video-assisted thyroidectomy. J Am Coll Surg 194:610–614

Miccoli P, Berti P, Raffaelli M, Conte M, Materazzi G, Galleri D (2001) Minimally invasive video-assisted thyroidectomy. Am J Surg 181:567–570

Miccoli P, Bellantone R, Mourad M, Walz M, Raffaelli M, Berti P (2002) Minimally invasive video-assisted thyroidectomy: multiinstitutional experience. World J Surg 26:972–975

Miccoli P, Berti P, Raffaelli M, Materazzi G, Baldacci S, Rossi G (2001) Comparison between minimally invasive video-assisted thyroidectomy and conventional thyroidectomy: a prospective randomised study. Surgery 130:1039–1043

Bellantone R, Lombardi CP, Bossola M, Boscherini M, De Crea C, Alesina PF, Traini E (2002) Video-assisted vs conventional thyroid lobectomy—a randomized trial. Arch Surg 137:301–304

Lombardi CP, Raffaelli M, Princi P, Lulli P, Rossi ED, Fadda G, Bellantone R (2005) Safety of video-assisted thyroidectomy versus conventional surgery. Head Neck 27:58–64

Miccoli P, Elisei R, Materazzi G, Capezzone M, Galleri D, Pacini F, Berti P, Pinchera A (2002) Minimally invasive video-assisted thyroidectomy for papillary carcinoma: a prospective study of its completeness. Surgery 132:1070–1074

Bellantone R, Lombardi CP, Raffaelli M, Alesina PF, De Crea C, Traini E, Salvatori M (2003) Video-assisted thyroidectomy for papillary thyroid carcinoma. Surg Endosc 17:1604–1608

Lombardi CP, Raffaelli M, Modesti C, Boscherini M, Bellantone R (2004) Video-assisted thyroidectomy under local anesthesia. Am J Surg 187:515–518

Shaha AR (2004) Implications of prognostic factors and risk group in the management of differentiated thyroid cancer. Laryngoscope 114:393–402

Bellantone R, Lombardi CP, Raffaelli M, Boscherini M, Alesina PF, Princi P (2002) Central neck lymph node removal during minimally invasive video-assisted thyroidectomy for thyroid carcinoma: a feasible and safe procedure. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 12:181–185

Siperstein AE, Berber E, Morkoyun E (2002) The use of the harmonic scalpel vs conventional knot tying for vessel ligation in thyroid surgery. Arch Surg 137:137–142

Acknowledgement

No competing interest is declared for this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lombardi, C.P., Raffaelli, M., Princi, P. et al. Video-assisted thyroidectomy: report of a 7-year experience in Rome. Langenbecks Arch Surg 391, 174–177 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-006-0023-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-006-0023-y