Abstract

Background and aims

The aim of this study was to analyze the ability of a training module on a virtual laparoscopic simulator to assess surgical experience in laparoscopy.

Methods

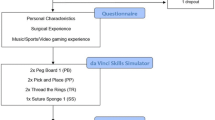

One hundred and fifteen participants at the 120th annual convent of the German surgical society took part in this study. All participants were stratified into two groups, one with laparoscopic experience of less than 50 operations (group 1, n=61) and one with laparoscopic experience of more than 50 laparoscopic operations (group 2, n=54). All subjects completed a laparoscopic training module consisting of five different exercises for navigation, coordination, grasping, cutting and clipping. The time to perform each task was measured, as were the path lengths of the instruments and their respective angles representing the economy of the movements. Results between groups were compared using χ2 or Mann–Whitney U-test.

Results

Group 1 needed more time for completion of the exercises (median 424 s, range 99–1,376 s) than group 2 (median 315 s, range 168–625 s) (P<0.01). Instrument movements were less economic in group 1 with larger angular pathways, e.g. in the cutting exercise (median 352°, range 104–1,628° vs median 204°, range 107–444°, P<0.01), and longer path lengths (each instrument P<0.05).

Conclusion

As time for completion of exercises, instrument path lengths and angular paths are indicators of clinical experience, it can be concluded that laparoscopic skills acquired in the operating room transfer into virtual reality. A laparoscopic simulator can serve as an instrument for the assessment of experience in laparoscopic surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Objective assessment of laparoscopic psychomotor skills is of increasing importance. This assessment used to be difficult to achieve because of measurement difficulties associated with the reliability and validity of assessing surgical skills in vivo and in the laboratory. Virtual reality (VR) has recently been established to overcome these problems and has become a useful tool in the objective psychomotor assessment of laparoscopists [1–7]. It could be shown that a laparoscopic skills assessment device (SAD) can discern levels of laparoscopic manipulative skill, proving the VR SAD to be sensitive and specific for measuring skills relevant for laparoscopic surgery [8–10]. Laparoscopic simulation was also shown to make objective assessments of the acquisition of laparoscopic skills in surgical training [5]. The majority of studies have been performed on the Minimal Invasive Surgical Trainer (MIST), and most studies available up to date on virtual reality systems and their face, concurrent, construct and content validity have been conducted on mostly smaller numbers of participants.

A recent study by Gallagher et al. [2] on 195 experienced surgeons highlighted the importance of establishing criteria levels and performance objectives for laparoscopic performance assessment to determine surgical competence. For laparoscopic surgery in Germany, only one small study consisting of 27 participants from a single institution is available so far [11].

The aim of the present study was to test the ability of the LapSim laparoscopic simulator to assess existing clinical laparoscopic experience in German surgeons and thereby further validate its use in surgical assessment and education.

Materials and methods

From 29th of April until 2nd of May 2003, 115 participants at the 120th annual convent of the German surgical society gave their consent and took part in this study. All participants were stratified into two groups, group 1 with laparoscopic experience of less than 50 operations and group 2 with experience of more than 50 laparoscopic operations. Laparoscopic skills were objectively measured by performing tasks on the LapSim laparoscopic simulator system. It is based on a PC, linked to a jig containing two laparoscopic instruments and a diathermy pedal, and movement is translated into a real-time graphic display. The system used does not possess haptic feedback. All 115 subjects completed a laparoscopic training module consisting of five different exercises for navigation, coordination, grasping, cutting and clipping. This module was performed once by each participant with a supervisor being at the device for assistance at all times. The tasks were of progressive difficulty; the navigation task begins with bilateral movements where virtual spheres appear and have to be touched with the virtual instruments’ tips. The coordination task requires the participant to hold a camera with one hand and locate a virtual ball, pick it up with the other instrument and transfer it into a virtual sphere. In the grasping exercise, vertical pipes need to be grasped, pulled from the ground and placed into a sphere with alternating hands. As with all tasks, this is repeated for a couple of times. In the cutting exercise, once a moving sphere has been grasped and stretched to a certain degree, a coloured endpiece appears, which has to be removed using virtual coagulation. In the last exercise, a virtual vessel needs to be clipped in required areas and then cut in half. The time to perform each task was measured, as were the path lengths of the instruments and their respective angles representing surrogate markers for the economy of the movements. Tissue damage was also recorded.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 11.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Normally distributed continuous data are given as mean (standard deviation) and non-normally distributed data as median (range). All continuous data were compared between both groups by Mann–Whitney U-test. Categorical data were analyzed using χ2 test.

Results

Surgeons from group 2 were older, but there was no gender difference between the two groups, with 84% of all surgeons being male (Table 1). Group 1 needed a median of 424 s (range 99–1,376 s) to complete the exercises, whereas group 2 finished the whole task within median 315 s (range 168–625 s) (P<0.01; Table 2). The experienced group was faster throughout the single exercises; this difference did not reach significance in the coordination exercise. The exercises differed in their ability to differentiate experts from novices, with the cutting exercise showing the largest differences concerning time, path lengths and angular pathways of the instruments and inflicted tissue damage (Table 3).

Path lengths of the instruments in the cutting exercise were longer in group 1 in comparison to group 2 (Table 3, P<0.05, each instrument). Also, the angular paths of the instruments were larger among group 1 compared to group 2 (Table 3, P<0.01), except for the coagulation device in the cutting exercise (Table 3, P=0.1). Group 1 also caused more tissue damage when performing the tasks (P=0.01, Table 3) and showed altogether significantly worse results concerning time, economy of the movements and accuracy. To rule out a possible influence of the chosen grouping, additional data analysis was carried out, comparing surgeons who had performed less than 50 operations with surgeons having performed more than 100 laparoscopic procedures, and the significance of the data remained the same (data not shown).

Discussion

The majority of training in surgery still occurs on patients with direct mentoring by experienced surgeons during the procedure. Moreover, traditionally, it was assumed that a surgeon became proficient after performing a procedure a certain number of times or after a certain length of training, without an objective measurement of the actually acquired skill and not taking into account the variability in individual learning rates. With the widespread use of laparoscopic surgery and its particular demands such as the visual-proprioceptive conflict and reduced degrees of freedom of the surgical instruments in comparison to open surgery, assessment of laparoscopic psychomotor skills has become increasingly important. With an ever increasing effort to ensure standardized treatment for the safety of patients, many criteria levels and performance objectives have been established in the different specialties. Reports of serious complications have highlighted the importance of adequate training and evaluation before attempting surgical procedures on patients. Randomized studies could show that virtual reality training significantly reduces the error rate in the operating room [12–14]. So far, for laparoscopy, no objective national or international benchmarks exist at which to aim, as number of procedures and duration of training are only crude surrogate measures of skill. The traditional approach to training produces surgeons with considerably variable skills, which have only been subjectively assessed [2]. Gallagher et al. have recently published their study on 195 surgeons who reported to have completed more than 50 laparoscopic procedures. The aim of their study was to benchmark laparoscopic performance of this experienced group in different tasks on the well-established MIST VR simulator [2]. They found that between 2 and 12% of the surgeons performed more than two standard deviations from the mean, and Cuschieri [15] had previously estimated that between 5 and 10% may not ever acquire a sufficient level of skill to perform laparoscopic surgery. Objective assessments of the technical skills component of determining surgical competence are therefore essential right from the very beginning of surgical training as many other high-skill/high-risk professions have already established as state-of-the-art in their training.

So far, hardly any data have been available on the assessment of German laparoscopic surgeons. One small study on 27 surgeons from a single department had looked into the validity of a laparoscopic simulator as an assessment tool for German laparoscopic surgeons [11].

In the present study, a programmed module on the LapSim VR laparoscopy simulator could be shown to differentiate between more and less experience in 115 laparoscopic surgeons from different institutions after one completion of the five different tasks. This makes the system a feasible instrument allowing for a quick evaluation of basic technical skills. The results show that some exercises were less suited to the task of skills assessment than others, revealing limitations of the system. Interestingly, the coordination exercise failed to show a significant difference between experienced surgeons and beginners. This could be due to the relatively unrealistic nature of this exercise as described in Materials and Methods. It also needs to be noted that six surgeons from the experienced group actually performed worse than the median of beginners, whereas seven beginners performed better than the median of confirmed surgeons. These results do not allow the conclusions that these surgeons are either not competent laparoscopists or that the beginners are particularly talented. These subtleties cannot be answered by a single run through this particular simulator module. As it was not recorded whether participants had had prior exposure to laparoscopic simulators, above-average results especially in beginners might be influenced by this and not necessarily reflect above-average surgical aptitude. The present module is also not suited to assess the more advanced aspects of surgical strategy or choosing the right dissection level. Therefore, the module needs to be modified and the different tasks reprogrammed and revalidated to be better suited for more detailed assessment. It is a prerogative that these instruments will be further developed to become a reliable testing standard. The achievement of technical skills in terms of basic abilities is of course only the very first step in the course of laparoscopic surgical education. It goes without saying, and stands in no contradiction to the above said, that a simulator can never replace clinical training and tutoring through an experienced surgeon. Moorthy et al. [16] have most recently recommended that the surgical community should follow the example of other high reliability organizations such as aviation and should design training programs, where continuous assessment is an integral part of training. This will essentially lead to a safer, objectively assessed intraoperative performance with improved quality of care for patients.

From the existing data in the literature, it can be concluded that virtual laparoscopy is a valuable tool to train surgical beginners without endangering patients. Our study has added the aspect that virtual laparoscopy furthermore offers to reliably assess basic laparoscopic abilities in inexperienced as well as experienced surgeons.

References

Gallagher AG, Lederman AB, McGlade K, Satava RM, Smith CD (2004) Discriminative validity of the Minimally Invasive Surgical Trainer in Virtual Reality (MIST-VR) using criteria levels based on expert performance. Surg Endosc 18:660–665

Gallagher AG, Smith CD, Bowers SP, Seymour NE, Pearson A, McNatt S, Hananel D, Satava RM (2003) Psychomotor skills assessment in practicing surgeons experienced in performing advanced laparoscopic procedures. J Am Coll Surg 197:479–488

Gallagher AG, Satava RM (2002) Virtual reality as a metric for the assessment of laparoscopic psychomotor skills. Learning curves and reliability measures. Surg Endosc 16:1746–1752

Gallagher AG, Richie K, McClure N, McGuigan J (2001) Objective psychomotor skills assessment of experienced, junior, and novice laparoscopists with virtual reality. World J Surg 25:1478–1483

McNatt SS, Smith CD (2001) A computer-based laparoscopic skills assessment device differentiates experienced from novice laparoscopic surgeons. Surg Endosc 15:1085–1089

Schijven M, Jakimowicz J (2003) Construct validity: experts and novices performing on the Xitact LS500 laparoscopy simulator. Surg Endosc 17:803–810

Taffinder N, Sutton C, Fishwick RJ, McManus IC, Darzi A (1998) Validation of virtual reality to teach and assess psychomotor skills in laparoscopic surgery: results from randomised controlled studies using the MIST VR laparoscopic simulator. Stud Health Technol Inform 50:124–130

Grantcharov TP, Bardram L, Funch-Jensen P, Rosenberg J (2003) Learning curves and impact of previous operative experience on performance on a virtual reality simulator to test laparoscopic surgical skills. Am J Surg 185:146–149

Grantcharov TP, Rosenberg J, Pahle E, Funch-Jensen P (2001) Virtual reality computer simulation—an objective method for evaluation of laparoscopic surgical skills. Surg Endosc 15:242–244

Grantcharov TP, Bardram L, Funch-Jensen P, Rosenberg J (2003) Impact of hand dominance, gender, and experience with computer games on performance in virtual reality laparoscopy. Surg Endosc 17:1082–1085

Hassan I, Sitter H, Schlosser K, Zielke A, Rothmund M, Gerdes B (2004) A virtual reality simulator for objective assessment of surgeons’ laparoscopic skill. Chirurg. Online first, DOI: 10.1007/s00104-004-0936-3

Grantcharov TP, Kristiansen VB, Bendix J, Bardram L, Rosenberg J, Funch-Jensen P (2004) Randomized clinical trial of virtual reality simulation for laparoscopic skills. Br J Surg 91:146–150

Seymour NE, Gallagher AG, Roman SA, O’Brien MK, Bansal VK, Andersen DK, Satava RM (2002) Virtual reality training improves operating room performance: results of a randomized, double-blinded study. Ann Surg 236:458–463

Hyltander A, Liljegren E, Rhodin PH, Lonroth H (2002) The transfer of basic skills learned in a laparoscopic simulator to the operating room. Surg Endosc 16:1324–1328

Cuschieri A (1995) Whither minimal access surgery: tribulations and expectations. Am J Surg 169:9–19

Moorthy K, Munz Y, Sarker SK, Darzi A (2003) Objective assessment of technical skills in surgery. BMJ 327:1032–1037

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of Tyco Healthcare Germany, who provided part of their exhibition area to perform this study during the annual meeting of the German Surgical Society in Munich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Langelotz, C., Kilian, M., Paul, C. et al. LapSim virtual reality laparoscopic simulator reflects clinical experience in German surgeons. Langenbecks Arch Surg 390, 534–537 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-005-0571-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-005-0571-6