Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the effects of shift work schedules on sleep quality and mental health in female nurses in south Taiwan.

Methods

This study recruited 1,360 female registered nurses in the Kaohsiung area for the first survey, and among them, 769 nurses had a rotation shift schedule. Among the 769 rotation shift work nurses, 407 completed another second survey 6–10 months later. Data collection included demographic variables, work status, shift work schedule, sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index), and mental health (Chinese Health Questionnaire-12).

Results

Nurses on rotation shift had the poor sleep quality and mental health compared to nurses on day shift. The nurses on rotation shift had a relatively higher OR of reporting poor sleep quality and poor mental health (OR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.57–3.28; and OR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.39–2.63, respectively). Additionally, rotation shift nurses who had ≥2 days off after their most recent night shifts showed significantly improved sleep quality and mental health (PSQI decreased of 1.23 and CHQ-12 decreased of 0.86, respectively). Comparison of sleep quality between the first and second surveys showed aggravated sleep quality only in nurses who had an increased frequency of night shifts.

Conclusion

Female nurses who have a rotation shift work schedule tend to experience poor sleep quality and mental health, but their sleep quality and mental health improve if they have ≥2 days off after their most recent night shifts. This empirical information is useful for optimizing work schedules for nurses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

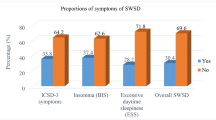

Night shift work is common and is an essential work rotation for nurses since patients in hospitals need 24-hour care. Hence, the detrimental effect of working a night shift is an important occupational hazard of nurses. Working a night shift can affect the sleep/wake cycle by disrupting the synchronous relationship between the natural circadian rhythm of the body and the environment. Studies show that at least 75% of shift workers are affected by sleep disturbance (Akerstedt et al. 2008) and 32.1% of night and 26.1% of rotating shift workers have insomnia or excessive sleepiness (Drake et al. 2004). Compared to nurses who work day shifts, those work rotation shifts and fixed night shifts are 2.82 and 1.80 times more likely to have poor sleep quality, respectively (Gold et al. 1992).

Shift work can also adversely affect psychological health and well-being. A night shift work schedule is associated with increased risk of poor mental health and anxiety/depression (Bara and Arber 2009). One study demonstrated that 69.8% of nurses who worked night shift and rotation shift had poor mental health, whereas only 55.6% of those who worked day shift had poor mental health (Suzuki et al. 2004).

Since poor sleep quality and mental health of nurses can adversely affect the patient treatment, (Gold et al. 1992; Suzuki et al. 2004; Arimura et al. 2010), effectively arranging shift schedules to attenuate the effects of rotation work schedules among health workers is essential. Although the effects of shift work schedules have been studied in other occupations (Rosa and Colligan 1997; Knauth and Hornberger 2003), few studies have discussed the effects of rotation shift work schedules in nurses (Wilson 2002; Berger and Hobbs 2006), and no studies have provided evidence-based information about the optimal and appropriate rotation shift work. Thus, in addition to examine whether night shift work adversely affects sleep quality and mental health, this study also compared different night shift schedules in terms of their effects on sleep quality and mental health. The objective was to determine the sufficient amount of rest needed after a night shift and reduction in night shifts needed to attenuate the detrimental effect of night shift work.

Methods

Study population

The potential study subjects were female registered nurses aged 20–45 years old in the Kaohsiung metropolitan area of southwestern Taiwan, which included Kaohsiung city and county. This study was approved by the Kaohsiung Nursing Association and Internal Review Board of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (KMUH-IRB-940086).

Two of the strategies recommended by Kaohsiung City and Kaohsiung County Nurse Associations were used to recruit study subjects. First, the nursing department supervisors of seven hospitals (two medical centers and five regional/district hospitals) in Kaohsiung city were willing to assist in distributing informed consent forms to their nurses. Of the total number of consent forms distributed, 882 signed informed consent forms were retrieved by July, 2005. A self-administrated structured questionnaire was then mailed to 882 nurses who gave consent to the study and 456 (51.7%) responded.

The name and address of the remaining 7,173 nurses were then obtained from the Kaohsiung City and County Nurse Association. Of the 7,173 self-administrated structured questionnaires and informed consent forms mailed, 1,030 (14.4%) signed informed consent forms and completed questionnaires were retrieved from July 2005 to October 2005.

In April 2006, 776 follow-up questionnaires were mailed to those who reported working rotation shift schedules in the first questionnaire information. Of these, 508 (65.5%) responses were retrieved.

Measurement

Demographic variables

Demographic variables included age, marital status, number of children, duration of employment, and medical center (yes or no). Compared to men, women in Chinese populations tend to assume more responsibilities for family care even though they have their own jobs. Thus, the variables of marital status and number of children may confound the relation between nursing works and sleep quality and mental health. In addition, data regarding hospital size and duration of employment were also collected, because they were probably related to physical and mental load.

Shift schedule and shift work arrangement

Workplace and work schedule were evaluated by questionnaires, and shift work was divided into three main work schedules: day shift, non-night shift, and rotation shift. A non-night shift was defined as a shift ending before midnight. Rotation shift was defined as a work schedule that included the day shift (from 8 AM to 4 PM), evening shift (from 4 PM to 12 midnight or from 2 PM to 10 PM), and night shift (from 12 midnight to 8 AM).

Nurses who worked rotation shift were asked three further questions about their work schedule: 1. How frequently did your shift change in the last 2 months?; 2. How many days off did you receive when you switched from the night shift to other shifts?; 3. In the last 2 months, how many night shifts did you work?

Sleep quality

Sleep Quality was measured by Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), which measures self-reported sleep habits over the last month (Buysse et al. 1989). The Index measures seven components using nineteen individual items. The total score ranges from 0 to 21. To fit the characteristic of sleep pattern in the study population, the original questions “When have you usually gone to bed at night?” and “When have you usually gotten up in the morning?” were modified as “How long have you slept between going to bed and getting up?” Higher scores reflected poorer overall sleep quality. A previous study of primary insomniacs and healthy controls in community-dwelling adults reported that the cutoff score of 5 in the Chinese version PSQI has a sensitivity and specificity of 98 and 55%, respectively (Tsai et al. 2005).

Mental health

The Chinese Health Questionnaire 12-item (CHQ-12) was used to evaluate the mental health status. The CHQ-12 was translated from General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) and modified by adding culturally relevant items (Cheng and Williams 1986). The 12-item self-rated CHQ-12 was designed to assess nonorganic and nonpsychotic mental disorder in a population. The total score ranged from 0 to 12 where a higher total CHQ-12 score indicated worse mental health. The optimal cutoff point was 3/4 by relative operating characteristic (ROC) analysis (Chong and Wilkinson 1989). The sensitivity and specificity of CHQ-12 were 77.8 and 76.9%, respectively; therefore, only scores ≥4 score were considered indicators of poor mental health (Chong and Wilkinson 1989).

Statistical analysis

Of the 1,486 questionnaires received, 45 questionnaires were excluded because they did not provide shift schedule information, and 81 were excluded because they did not provide sufficient information to calculate of PSQI or/and CHQ-12 scores. The remaining 1,360 nurses were recruited for the final analysis.

Among the 508 questionnaires received in the second survey, 17 were excluded because the respondent quit the job, 33 were excluded because the respondent transferred to day shift. Another 13 were excluded because they did not provide sufficient information to calculate PSQI or/and CHQ-12 scores. The remaining 445 questionnaires were then merged with the 769 questionnaires received from respondent who worked rotation shift according to the first survey. After excluding 38 incomplete questionnaires from first survey, the second phase of the study analyzed 407 participants.

The participants were categorized by shift work schedules as day shift, non-night shift, and rotation shift. Demographic variables, sleep quality, and mental health were compared among these three groups using Chi-squared test and ANOVA (analyses of variances) test. Significant demographic variables observed in the univariate analysis, including age, duration of employment, marital status, number of children, and medical center (yes or no), were included in the multivariate models. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) tests were used to compare the three groups after adjusting for other factors on the sleep quality and mental health. Linear and logistic regression models were further used to adjust for potential confounding factors.

For those who worked rotation shift, the adjusted mean (SE, standard error) of the sleep quality and mental health was described in the shift arrangement variables (frequency of shift change, number of days off after night shift and cumulative night shift days), and these shift arrangement variables were compared separately after ANCOVA tests of demographic factors. Chi-squared test of PSQI categories and CHQ-12 categories across the shift arrangement variables and the regression analyses were performed to examine the independent effect of groups on the PSQI and CHQ-12 scores.

Changes in sleep quality and mental health scores were further compared between the primary and secondary surveys using paired t test stratified by groups with unchanged, increased, and decreased frequency of night shifts in the last two months between these two surveys. The JMP 8.0 for Windows was used to perform all the statistical analyses, and the significance level (P value) was set to 0.05.

Results

The mean age of the 1,360 participants was 29.9 years, and 56.5% of the subjects worked rotation shift. More than one-half of the nurses in the rotation shift were younger than 30 years (58.4%), were single (67.5%), and had no children (72.7%), and these proportions significantly differed from day shift and non-night shift workers (Table 1).

Sleep quality and mental health were significantly worse in the rotation shift (adjusted mean PSQI, 8.99; adjusted mean CHQ-12, 4.98) than in other work schedules after adjusting for age, duration of employment, marital status, number of children, and medical center (yes vs. no) (Table 2). Compared to nurses who worked day shift, the average PSQI and CHQ-12 scores significantly increased (1.59 and 0.72, respectively) in nurses who worked rotation shift after adjusting for confounding factors (Table 2).

At cut-points of >5 in PSQI and ≥4 in CHQ-12, 78 and 58% of the study participants had poor sleep quality and mental health, respectively. The percentages of poor sleep quality and mental health were even higher in nurses on rotation shift (84.3 and 65.9%) (Table 3). After adjusting for other covariates, nurses who worked rotation shift had a 2.26-fold (95% CI = 1.57–3.28) higher risk of poor sleep quality and a 1.91-fold (95% CI = 1.39–2.26) higher risk of poor mental health compared to nurses who worked day shift.

Among the 769 rotation shift nurses, average PSQI and CHQ-12 were significantly decreased in those who had received ≥2 days off after the last night shift than in those who had received 1 day off (Table 4). The poor sleep quality and mental health were also ameliorated in the group of nurses with ≥2 days off after their last night shift compared to those with 1 day off since their last night shift. However, only the amelioration of poor mental health reached to be statistically significant (Table 5). In addition, the more days of night shift in the 2 months, the higher averaged PSQI scores were found (Table 4).

In the 407 nurses on rotation shift, PSQI scores did not significantly differ between the first and second surveys (paired t test, P value = 0.6374). However, in the group of nurses who indicated that their night shift had increased between the first and second surveys, PSQI scores had significantly increased by 0.82 between the first and second surveys (Table 6). In contrast, all mean CHQ-12 scores significantly increased between the first and second years regardless of the change in frequency of night shifts (Table 6).

Discussion

This study showed that nurses who worked rotation shift appeared to have poorer sleep quality and mental health compared to the two other groups those worked without night shift. Of nurses who worked night shift, those with 2 days off after the last night shift had improved sleep quality and mental health. Comparison of the first and second surveys indicated that increased frequency of night shifts worsened sleep quality. However, decreased frequency of night shifts apparently did not improve sleep quality. In all of these nurses, mental health was worse than that in the previous year.

The night shift nurses in this study had the worst sleep quality (PSQI score: 9.04) compared to those who worked day shift (PSQI score: 7.32) or non-night shift (PSQI score: 7.20). This finding is consistent with other studies (Ruggiero 2005; van Mark et al. 2010). Ruggiero reported that nurses who worked a fixed night shift and rotation shift had higher PSQI scores (7.86 and 7.31, respectively) compared to those who worked day shift (PSQI score, 6.37) (Ruggiero 2005). A study of the general population by van Mark et al. (2010) also reported that shift workers had a significantly higher mean PSQI score compared to day workers (6.73 vs. 4.66) regardless of occupation. In another study that used Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) in a questionnaire survey, Drake et al. (2004) reported that the prevalence of insomnia or excessive sleepiness was 32 and 26% in night and rotation shift workers, respectively, but only 18% in day workers.

A plausible biological explanation for the association between night shift work and sleep quality might be the endogenous signal of darkness, melatonin, which is an important component of the internal timekeeping system (Pandi-Perumal et al. 2008). Melatonin promotes falling asleep and sleep by inhibiting suprachiasmatic nucleus, and the secretion of melatonin is suppressed by light. Hence, alteration of melatonin levels by extended exposure to light could trigger the desynchronicity between the internal hormonal environment and the external environment, which may explain why nurses who work night shift are susceptible to poor sleep quality.

Sufficient rest after a night shift may also attenuate the disturbance of sleep for nurses with rotating schedules. Internal circadian rhythms adjust very slowly in the sleep/wake cycle, and shift workers can often return to night sleep and daytime activities while their altered sleep/wake schedule is not maintained long enough to allow sufficient adaptation (Lamond et al. 2003). Hence, the ergonomic recommendation is that at least 2 days off after the last night for decreasing the reduction in sleep before morning shift (Rosa and Colligan 1997; Knauth and Hornberger 2003; Berger and Hobbs 2006). After a night shift, two days off are generally recommended on application of shift system, especially in industries. However, no empirical data support that this recommendation is widely observed in nurses who work rotation schedule. This study found that nurses who had 2 or more days off after night shifts had significantly improved sleep quality compared with those who with only one day off, which supported the general recommendation.

Since an increased frequency of night shifts can worse sleep, successive night shifts should be minimized to avoid difficulty adapting to circadian rhythms and to avoid accumulation of sleep deficits. Schernhammer et al. (2004) indicated that the number of nights worked within a 2-week period has a significant negative correlation with melatonin level (r = −0.30, P = 0.008). In their study, subjects who worked over 4, 1–4, and 0 night shifts within the past 2 weeks had urinary creatinine-adjusted 6-sulfatoxymelatonin concentration (ng/ml) of 12, 18, and 27, respectively. The results of the current study and follow-up study agreed that the frequency of night shifts within a 2-month period correlated negatively with sleep. Additionally, nurses who had worked an increased number of night shifts between first and second survey had significantly worse sleep quality during the second year compared to the first year, and their average PSQI increased from 8.87 to 9.68 (P value = 0.007). These results suggest that appropriately limiting the frequency of night shift might attenuate their detrimental effects.

This high stress of shift work may also result in poor mental health if (Conway et al. 2008) social marginalization (Costa 2003) and family conflict (Fujimoto et al. 2008) because of the shift work decrease satisfaction of physical and psychical needs. Epidemiological and electroencephalographic studies also show that sleep disturbance and chronic insomnia are common triggers of depression and as predictors of depressive disorder (Srinivasan et al. 2009). In nurses, deterioration of mental health may be detrimental not only to their own physical health but also to the health of their patients. The previous studies indicate that medical errors correlate negatively with mental health status (Suzuki et al. 2004; Arimura et al. 2010).

This study also showed that the rotation shift group had significantly poorer mental health compared to the other two groups because of their poor sleep quality. Among the nurses in the rotation shift, the CHQ-12 score was better in those who had received at least 2 days off after since their last night shift than in those who had received only 1 day off (CHQ-12 score: 4.44 vs. 5.26). Therefore, adequate rest time apparently benefits both mental health and sleep quality.

The second survey further showed that all nurses in the rotation shift group had significantly worse mental health compared to the previous year, and those with a high frequency of shift work seemed to the largest decrease in the mental health. These observations suggest that increased frequency of shift work might be associated with detrimental mental health. The trend of poor mental health of all nurses also reflected that nurses are to be in less friendly situations. This is a wake-up alarm for working environment of nurses and quality of patient care. In recent years, hospital accreditation for regional/district hospitals and the payment system for the National Health Insurance Scheme have increased the work load of nurses in Taiwan. In addition to caring for patients, nurses need to provide documents required for hospital accreditation and documents required by the National Health Insurance system. However, a few nurses received formal education and training to perform these additional duties, which may detrimentally affect their mental health. Further studies of insufficiencies in the training of nurses would help hospital managers and nursing educators recognize and further minimize the impact.

The main limitation of this study is the low response rate. However, the mean ages of respondents in the initial survey performed by Kaohsiung City and County Nurses Association were 30.2 and 29.9 years, respectively, which were similar to the mean ages in this study (30.1 and 29.7 years, respectively). Therefore, we are confident that our finding can be representative of Kaohsiung area nurses aged 20–45 years.

This study found that female nurses who work rotation shift experience poor sleep quality and mental health and that 2 or more days off after the last night shift might improve their sleep quality and mental health. These findings provide useful empirical information for arranging shift schedules. To adjust rotation schedules to improve the health of nurses and the care of patients, further interventional or longitudinal research is needed to clarify the effects of differing shift schedules of nurses. Future studies may consider whether the managers of hospital nursing departments should reconsider the appropriate number of days off after the last night shift and the appropriate number of consecutive night shifts.

References

Akerstedt T, Ingre M, Broman JE, Kecklund G (2008) Disturbed sleep in shift workers, day workers, and insomniacs. Chronobiol Int 25(2):333–348. doi:10.1080/07420520802113922

Arimura M, Imai M, Okawa M, Fujimura T, Yamada N (2010) Sleep, mental health status, and medical errors among hospital nurses in Japan. Ind Health 48(6):811–817. doi:JST.JSTAGE/indhealth/MS1093

Bara AC, Arber S (2009) Working shifts and mental health–findings from the British Household Panel Survey (1995–2005). Scand J Work Environ Health 35(5):361–367

Berger AM, Hobbs BB (2006) Impact of shift work on the health and safety of nurses and patients. Clin J Oncol Nurs 10(4):465–471

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ (1989) The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28(2):193–213. doi:0165-1781(89)90047-4

Cheng TA, Williams P (1986) The design and development of a screening questionnaire (CHQ) for use in community studies of mental disorders in Taiwan. Psychol Med 16(2):415–422

Chong MY, Wilkinson G (1989) Validation of 30- and 12-item versions of the Chinese Health Questionnaire (CHQ) in patients admitted for general health screening. Psychol Med 19(2):495–505

Conway PM, Campanini P, Sartori S, Dotti R, Costa G (2008) Main and interactive effects of shiftwork, age and work stress on health in an Italian sample of healthcare workers. Appl Ergon 39(5):630–639. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2008.01.007

Costa G (2003) Shift work and occupational medicine: an overview. Occup Med (Lond) 53(2):83–88

Drake CL, Roehrs T, Richardson G, Walsh JK, Roth T (2004) Shift work sleep disorder: prevalence and consequences beyond that of symptomatic day workers. Sleep 27(8):1453–1462

Fujimoto T, Kotani S, Suzuki R (2008) Work-family conflict of nurses in Japan. J Clin Nurs 17(24):3286–3295. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02643.x

Gold DR, Rogacz S, Bock N, Tosteson TD, Baum TM, Speizer FE, Czeisler CA (1992) Rotating shift work, sleep, and accidents related to sleepiness in hospital nurses. Am J Public Health 82(7):1011–1014

Knauth P, Hornberger S (2003) Preventive and compensatory measures for shift workers. Occup Med (Lond) 53(2):109–116

Lamond N, Dorrian J, Roach GD, McCulloch K, Holmes AL, Burgess HJ, Fletcher A, Dawson D (2003) The impact of a week of simulated night work on sleep, circadian phase, and performance. Occup Environ Med 60(11):e13

Pandi-Perumal SR, Trakht I, Srinivasan V, Spence DW, Maestroni GJ, Zisapel N, Cardinali DP (2008) Physiological effects of melatonin: role of melatonin receptors and signal transduction pathways. Prog Neurobiol 85(3):335–353. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.04.001

Rosa RR, Colligan MJ (1997) Plain language about shiftwork

Ruggiero JS (2005) Health, work variables, and job satisfaction among nurses. J Nurs Adm 35(5):254–263. doi:00005110-200505000-00009

Schernhammer ES, Rosner B, Willett WC, Laden F, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE (2004) Epidemiology of urinary melatonin in women and its relation to other hormones and night work. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13(6):936–943

Srinivasan V, Pandi-Perumal SR, Trakht I, Spence DW, Hardeland R, Poeggeler B, Cardinali DP (2009) Pathophysiology of depression: role of sleep and the melatonergic system. Psychiatry Res 165(3):201–214. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2007.11.020

Suzuki K, Ohida T, Kaneita Y, Yokoyama E, Miyake T, Harano S, Yagi Y, Ibuka E, Kaneko A, Tsutsui T, Uchiyama M (2004) Mental health status, shift work, and occupational accidents among hospital nurses in Japan. J Occup Health 46(6):448–454. doi:JST.JSTAGE/joh/46.448

Tsai PS, Wang SY, Wang MY, Su CT, Yang TT, Huang CJ, Fang SC (2005) Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (CPSQI) in primary insomnia and control subjects. Qual Life Res 14(8):1943–1952. doi:10.1007/s11136-005-4346-x

van Mark A, Weiler SW, Schroder M, Otto A, Jauch-Chara K, Groneberg DA, Spallek M, Kessel R, Kalsdorf B (2010) The impact of shift work induced chronic circadian disruption on IL-6 and TNF-alpha immune responses. J Occup Med Toxicol 5:18. doi:10.1186/1745-6673-5-18

Wilson JL (2002) The impact of shift patterns on healthcare professionals. J Nurs Manag 10(4):211–219. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2834.2002.00308.x.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their thanks to Kaohsiung County Nurses Association and Kaohsiung City Nurses Association. The project was supported by the Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (No: ISOH95-M318, IOSH96-M318) and the National Science Council (No: NSC97-2314-B-037-018-MY3).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, PC., Chen, CH., Pan, SM. et al. Atypical work schedules are associated with poor sleep quality and mental health in Taiwan female nurses. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 85, 877–884 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-011-0730-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-011-0730-8