Abstract

Objectives

The working population is aging and a shortage of workers is expected in the construction industry. As a consequence, it is considered necessary that construction workers extend their working life. The purpose of this study was to explore factors associated with construction workers’ ability and willingness to continue working until the age of 65.

Methods

In total, 5,610 construction workers that participated in the Netherlands Working Conditions Survey filled out questionnaires on demographics, work-related and health-related factors, and on the ability and willingness to continue working until the age of 65. Logistic regression analyses were applied.

Results

Older workers were more often able, but less willing, to continue working until the age of 65. Frequently using force, lower supervisor support, lower skill discretion, and the occurrence of musculoskeletal complaints were associated with both a lower ability and willingness to continue working. In addition, dangerous work, occasionally using force, working in awkward postures, lack of job autonomy, and reporting emotional exhaustion were associated with a lower ability to continue working, whereas working overtime was associated with a higher ability. Furthermore, low social support from colleagues was associated with a higher willingness.

Conclusion

In addition to physical job demands, psychosocial job characteristics play a significant role in both the ability and willingness to continue working until the age of 65 in construction workers. Moreover, preventing musculoskeletal complaints may support the ability and willingness to continue working, whereas preventing emotional exhaustion is relevant for the ability to continue working.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As in many countries throughout the world, the Dutch construction industry faces the challenges of a rapidly decreasing and aging working population (Eurostat 2008; United Nations 2007). This development is partly explained by the fact that less young workers are entering the construction industry (Beereboom et al. 2005; Griffiths 1997; Sijpersma 2003). Besides, many workers leave the labor market before their official retirement age (Romans 2007; Van Nimwegen and Beets 2006). The age of retirement among construction workers is strongly influenced by collective agreements in which workers are allowed to retire at an earlier age than the official retirement age of 65. However, to encounter the expected shortages of construction workers in the next decades, it is important that more construction workers prolong their (healthy) working life until the official retirement age. Although the willingness to continue working until the age of 65 in the construction industry increased from 25% in 2007 to 36% in 2009, the percentage of workers who thought they were able to continue working until the age of 65 only increased slightly (4%) in these years (Koppes et al. 2011; Van den Bossche et al. 2008). A previous report showed that the ability and willingness are strong predictors for actual taking retirement (Ybema et al. 2010). Thus, in order to support sustainable employability of construction workers until and after the official retirement age, there is a need to develop policies and intervention programs to promote the ability and willingness to continue working.

To date, knowledge on determinants of sustainable employability among blue-collar workers is lacking. Studies on determinants of early retirement among blue-collar workers found that, in addition to collective agreements, mainly physically demanding tasks such as heavy lifting (Szubert and Sobala 2005) and extreme bending of the back (Lund et al. 2001) were important predictors of early retirement. In addition, blue-collar workers with a poor health condition more often retire early (Szubert and Sobala 2005; van den Berg et al. 2010b).

Although the previous studies provided knowledge on determinants of early retirement, this knowledge is insufficient for developing policies and intervention programs that promote sustainable employability of construction workers at an earlier stage. For that purpose, the focus on the determinants should move from early retirement toward the ability and the willingness to continue working until the retirement age. Thus, the objective of the present study was to explore the associations of demographic, work-related, and health-related factors with the ability and willingness to continue working until the age of 65 years in construction workers.

Methods

Study population and design

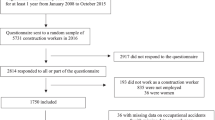

A cross-sectional study was performed, in which data from the Netherlands Working Conditions Surveys (NWCS) of 2007, 2008, and 2009 were used. The NWCS constitutes of a representative sample of the Dutch workforce in the 15–64 year age group, but excludes self-employed individuals (Van den Bossche et al. 2008). Each year, 80,000 individuals were sampled from the Dutch working population database of Statistics Netherlands. This database contains information on all jobs that fall under the worker national insurance schemes and are liable to income tax. Sampling was random, except for a 50% over-sampling of workers with lower response rates, namely workers under the age of 25 years and workers with a non-Western background. Individuals in the sample received the questionnaire mailed to their home address in the first week of November. After one or 2 weeks, reminders were sent to those who had not yet responded. Data collection was stopped after 2 months.

Questionnaires were filled out by 67,552 employees (28.1% of the total sample of workers). The responses were weighed for gender, age, sector, ethnic origin, level of urbanization, geographical region, and level of education, to obtain a sample that is representative for the distribution of these factors in all employees in the Netherlands. In all cases, weight coefficients and standard deviations fall within acceptable limits.

Of the 67,552 workers, 5,803 construction workers were selected for the present study. These workers were defined as those who were working as (a) painters, (b) plumbers, welders, fitters, (c) electricians, (d) assemblers, repairmen, mechanics, or (e) bricklayers, carpenters, and other construction workers. Due to the very small number of women (n = 120), only men were included in the present study (n = 5,683). Only those who had filled out both questions on the ability and willingness to continue working until the age of 65 were included (n = 5,610).

Measurement

The ability and willingness to continue working until the age of 65

The official retirement age in the Netherlands is 65 years. The ability to continue working until the age of 65 was assessed with a single question (“Do you think you are able to continue working in your current profession until the age of 65?”). Answer categories were “yes”, “no”, and “do not know” (Van den Bossche et al. 2008). Workers who answered “yes” were classified as being able to continue working in the current profession until the age of 65, whereas those who answered “no” or “do not know” were classified as not having the ability.

The willingness to continue working until the age of 65 was also assessed with a single question (“Would you like to work until the age of 65?”) with three answer categories (yes, no, and do not know). Workers who answered “yes” were classified as willing to continue working until the age of 65, whereas those who answered “no” or “do not know” were classified as not willing.

Demographic factors

Age was categorized into four groups, i.e., 15–34 years, 35–44 years, 45–54 years, and 55–64 years. Workers were also asked whether they had a partner, and whether their partner had a paid job.

Work-related factors

Working overtime was asked on a 3-point scale (no, incidentally, and structurally). Those who answered “incidentally” or “structurally” were categorized as “yes”, whereas the others were classified as “no”. Shift work and dangerous work were asked on a 3-point scale (no, yes sometimes, and yes regularly) Those who answered “yes sometimes” or “yes regularly” were categorized as “yes”, whereas the others were classified as “no”.

Three questions on physical job demands were derived from the Dutch Labour Force Survey (using force, working in awkward postures, and exposure to vibrations) with answers on a 3-point scale (no, yes sometimes, and yes regularly). The three physical job demands were interrelated with Spearman’s correlation coefficients varying from 0.55 to 0.60.

Questions on quantitative job demands, job autonomy, skill discretion, and social support were based on the Job Content Questionnaire (Karasek et al. 1998; Karasek 1985; Van den Bossche et al. 2008). Four items on a 4-point scale (never to always) were used to measure quantitative job demands. Job autonomy was measured with five items on a 3-point scale (no, yes sometimes, and yes regularly), and skill discretion was measured with three items on a 4-point scale (never to always). Co-worker support and supervisor support were measured separately with four items, each on a 4-point rating scale (1 = totally disagree; 4 = totally agree) derived from the Job Content Questionnaire (Karasek et al. 1998; Karasek 1985; Van den Bossche et al. 2008). Because of the skewed distributions, three levels (low, intermediate, and high) were distinguished using the 25th and 75th percentile scores of the continuous scales.

Emotional job demands were measured with three items derived from the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire on a four-point scale (never to always) (Kristensen and Borg 2000; Van den Bossche et al. 2008). Based on the skewed total score, three levels (low, intermediate, and high) were distinguished using the 25th and 75th percentile scores of the continuous scales.

Health-related factors

Emotional exhaustion was measured using five questions of the Utrecht Emotional Exhaustion Scale with answers on a 7-point scale ranging from never to every day (Schaufeli and Van Dierendonck 2000). Based on the cutoff value of 3.2 defined by Schaufeli and Van Dierendonck (2000), the skewed sum score was dichotomized into “no emotional exhaustion” and “emotional exhaustion”.

Regarding musculoskeletal symptoms, the questions were based on the Dutch Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (Hildebrandt et al. 2001; Hildebrandt 2001). Workers were asked to rate the occurrence of pain or discomfort in the neck or shoulders in the previous 12 months using two questions on a 5-point scale (never, once only but of a short duration, once only but of a long duration, more than once but always of a short duration, and frequent and prolonged). Workers who answered “never” on both questions were classified as having no musculoskeletal symptoms. Those who answered “more than once” or “frequent and prolonged” on one of the two questions were classified as frequently having musculoskeletal symptoms. Workers who answered “only once” were classified as having occasional neck or shoulder symptoms.

Statistical analyses

Logistic regression analyses were carried out in order to study the associations of demographic, work-related, and health-related factors with the ability and willingness to continue working until the age of 65. Separate models were constructed for the ability and for the willingness to continue working until the age of 65. First, univariate logistic regression analyses were performed to study the association between one independent variable and the dependent variable. The measure of association was expressed by the odds ratio (OR) and the 95% confidence interval. Odds ratios of the independent variables with a p value < 0.05 in the univariate regression analyses were selected for further analyses. Second, multivariate analyses were carried out using backward selection. Only variables with a p value of < 0.05 were retained in the final multivariate model. After construction of these models, independent variables that were not in the final model, but had a p value between < 0.2 in the univariate regression analyses were included one by one to evaluate their influence on the overall fit of the model. By default, age was retained in the multivariate models. In additional analyses, willingness to continue working was added to the final multivariate model of the ability to continue working and vice versa. Nagelkerke’s R 2 was used as measure for the explained variance of the multivariate models. All analyses were performed using version 17.0 of the Statistical Package of Social Sciences for windows (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study participants (n = 5,610), which included 316 painters (6%), 1,030 plumbers, welders, and fitters (18%), 1,072 electricians and assemblers (19%), 1,546 repairmen and mechanics (28%), and 1,646 bricklayers, carpenters, and other construction workers (29%). In total, 30% of the construction workers stated to be able to continue working in their current profession until the age of 65, whereas 29% of the construction workers were willing to continue working until the age of 65. The ability and willingness to continue working were significantly correlated (Spearman r = 0.29). While 50% of all construction workers stated they were neither able nor willing to continue working until the age of 65, only 15% of all workers stated they were able as well as willing to continue working.

Table 2 shows the univariate and multivariate associations of demographic, work-related, and health-related factors with the ability and the willingness to continue working until the age of 65. In the univariate analyses, all demographic, work-related, and health-related factors, except shift work, were significantly associated with the ability to continue working until the age of 65. In the multivariate model, construction workers between 45 and 54 years (OR 1.30; Table 2), or aged 55 years and older (OR 1.41), and those working overtime (OR 1.28) considered themselves more often able to continue working. Construction workers having dangerous work (OR 0.75) were less often able to continue working. With respect to physical job demands, occasionally or frequently using force (OR 0.71 and OR 0.44, respectively) and occasionally or frequently working in awkward postures (OR 0.76 and OR 0.47, respectively) were associated with a lower ability to continue working. Also, low or intermediate job autonomy (OR 0.61 and OR 0.82, respectively), low skill discretion (OR 0.70), and low or intermediate support from the supervisor (OR 0.58 and OR 0.76, respectively) were associated with a lower ability to continue working (Table 2). With respect to health-related factors, construction workers reporting emotional exhaustion (OR 0.62) and those reporting the occurrence of occasional or frequent musculoskeletal symptoms (OR 0.63 and OR 0.40, respectively) were less often able to continue working. The multivariate model explained 20% of variance of the ability to continue working until the age of 65. Addition of the willingness to continue working in the final model did not substantially influence the associations between the independent variables and the ability to continue working until the age of 65 (data not shown).

Regarding the willingness to continue working until the age of 65, several demographic, work-related, and health-related factors were significantly associated with the univariate analyses (Table 2).

Except for age and having a partner, a similar direction was found between the significant independent variables and the willingness to continue working as between these variables and the ability to continue working. However, most psychosocial factors (quantitative job demands, job autonomy, and emotional job demands) were not significant related with the willingness to continue working until the age of 65. In the multivariate model, workers aged 55 years and older (OR 0.56) were less willing to continue working. Furthermore, frequently using force (OR 0.71), intermediate skill discretion (OR 0.79), a low or intermediate social support from the supervisor (OR 0.59 and OR 0.72), and the occurrence of occasional or frequent musculoskeletal symptoms (OR 0.77 and OR 0.69, respectively) were associated with a lower willingness to continue working. Workers with low social support from colleagues (OR 1.37) were more often willing to continue working until the age of 65. The multivariate model explained 4% of the variance of the willingness to continue working until the age of 65. When adding the ability to continue working in the final model, this did not substantially influence the relationship between the independent variables and the willingness to continue working until the age of 65 (data not shown).

Discussion

The main findings of this study were that in a large population of Dutch construction workers, older workers were more often able, but less willing, to continue working in their current profession until the age of 65. In addition, using force, low skill discretion, lack of supervisor social support, and the occurrence of musculoskeletal complains were associated with both a lower ability and willingness to continue working until the age of 65. Moreover, working overtime, dangerous work, lower job autonomy, and emotional exhaustion were associated with the ability to continue working in the current profession until the age of 65, whereas social support from colleagues was associated with the willingness to continue working.

As mentioned in the introduction, literature on determinants of the ability and willingness to continue working in the current profession until the retirement among blue-collar workers is lacking. Therefore, to provide explanations for the findings of the current study, our findings were compared with studies investigating the determinants of early retirement in blue-collar workers.

Several factors were associated with the ability and willingness to continue working. Regarding the work-related factors, in accordance with previous studies (Lund et al. 2001; Szubert and Sobala 2005; van den Berg et al. 2010b), construction workers using force or working in awkward postures were less often able to continue working in the current profession until the age of 65. Frequently using force was also associated with a lower willingness to continue working until the age of 65. Moreover, not in line with the study of Lund et al. (2001), construction workers reporting a lack of skill discretion were less often able and willing to continue working until the age of 65. Furthermore, a lower support from the supervisor was related with both a lower ability and willingness to continue working until the age of 65. Although Lund et al. (2001) did not find that social support predicted an early retirement among blue-collar workers, social support from both colleagues and supervisors was found to postpone early retirement in a qualitative study (van den Berg et al. 2010b). This qualitative study found that more support from the supervisor could be defined as more rewards and appreciation (van den Berg et al. 2010b). Regarding health-related factors, the ability as well as the willingness to continue working were negatively related with poor physical health (i.e., the occurrence of musculoskeletal symptoms), which is in line with studies on the intention to retire (Heponiemi et al. 2008; Von Bonsdorff et al. 2010) and actual early retirement (van den Berg et al. 2010a; van den Berg et al. 2010b). Because of the high physical demands, construction workers have an increased risk to develop musculoskeletal disorders of the back or lower extremities (Boschman et al. 2011; de Zwart et al. 1997). As a consequence, construction workers with musculoskeletal complaints may experience more difficulties in meeting the high physical demands of their job such as lifting and carrying heavy loads or working in awkward postures (Welch et al. 2008, 2009).

Regarding factors that were only associated with the ability to continue working in the current profession until the age of 65, the results showed that a lack of job autonomy was associated with a lower ability to continue working. This was not in agreement with the study of Lund et al. (2001) who found no association between job autonomy and early retirement. Moreover, construction workers reporting emotional exhaustion were less often able to continue working. To date, no study reported about the role of emotional exhaustion and early retirement among blue-collar workers.

In addition to the factors associated with both the ability and willingness to continue working until the age of 65, the willingness to continue working was also influenced by social support from colleagues. Despite the fact that several factors were associated with the willingness to continue working, the combination of these factors explained only 4% of the variance. It is likely that the willingness to continue working is driven by other work-related factors than factors measured in the present study. Previous studies showed that work-related factors such as an appropriate effort–reward balance, more job control, challenging work, appreciation, competencies, and skills were important to prolong working lives of older workers (Proper et al. 2009; Siegrist et al. 2007). In addition to work-related factors, financial aspects (Nilsson et al. 2011; Proper et al. 2009), lifestyle factors (Alavinia and Burdorf 2008), and subjective life expectancy (Van Solinge and Henksens 2010) may influence whether older workers retire or not. These factors could also be relevant for the willingness and ability to continue working in construction workers.

To the current knowledge of the authors, the present study is the first study investigating the associations between several demographic, work-related and health-related factors, and the ability and willingness to continue working until the age of 65 in construction workers. A strength of the study is the unique dataset, which is large and representative for all employees in the Netherlands. Because of the large dataset, a large sample of workers at a specific industry where the issue of sustainable employability is at large (construction industry) could be included for the present study. Some methodological considerations deserve attention as well. The ability and the willingness to continue working were assessed with single-item questions, and one could question the reliability of these items. It remains unclear to what extent the variables in the present study predict whether construction workers will or will not leave the labor market. Nevertheless, a recent Dutch report showed that the questions on the ability and the willingness to continue working were strong predictors of early retirement in older workers (Ybema et al. 2010). Moreover, construction workers may have wrongly interpreted the question on the ability to continue working in their current profession until the age of 65. They may have interpreted “profession” in this question as their current “job”, leading to an underestimation of workers who are able to continue working in younger workers, who are more likely to change jobs than older workers. However, most construction workers, older as well as younger, work for the same employer for many years and do not change jobs often. Therefore, we believe that the possible wrongful interpretation of this question does not have notable consequences for this study. Furthermore, the dataset is large and representative for all employees in the Netherlands, but it is not clear to which degree the results can be generalized to construction workers in other countries. Nevertheless, these results are still of interest as they provide a first overview of factors that could be taken into account when developing interventions among construction workers to support sustainable employability.

Conclusion

In addition to physical job demands, psychosocial job characteristics play a significant role in both the ability and willingness to continue working until the age of 65 in construction workers. Moreover, preventing musculoskeletal complaints may support the ability and willingness to continue working, whereas preventing emotional exhaustion is relevant for the ability to continue working. More research is needed to identify what additional factors associated with the willingness to prolong the working life of construction workers.

References

Alavinia S, Burdorf A (2008) Unemployment and retirement and ill-health: a cross-sectional analysis across European countries. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 82:39–45

Beereboom H, Blomsma G, Corten I, Muchall S (2005) De bouwarbeidsmarkt in de periode 2005–2010 [The labour market of the construction industry in the period 2005–2010]. Economisch Instituut voor de Bouwnijverheid, Amsterdam

Boschman J, van der Molen H, Sluiter J, Frings-Dresen MH (2011) Occupational demands and health effects for bricklayers and construction supervisors: A systematic review. Am J Ind Med 54:55–77

De Zwart B, Broersen J, Frings-Dresen M, Van Dijk F (1997) Musculoskeletal complaints in the Netherlands in relation to age, gender and physically demanding work. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 70:352–360

Eurostat (2008) Europe in figures. Eurostat yearbook 2008. Eurostat European Commission, Luxembourg

Griffiths A (1997) Ageing, health and productivity: a challenge for the new millennium. Work & Stress 11:197–214

Heponiemi T, Kouvonen A, Vänskä J, Halila H, Sinervo T, Kivimäki M, Elovainio M (2008) Health, psychosocial factors and retirement intentions among Finnish physicians. Occup Med 58:406–412

Hildebrandt V (2001) Prevention of musculoskeletal disorders (Thesis). VU University, Amsterdam

Hildebrandt V, Bongers P, Van Dijk F, Kemper H, Dul J (2001) Dutch Musculoskeletal Questionnaire: description and basic qualities. Ergonomics 44:1038–1055

Karasek R (1985) Job content questionnaire and user’s guide. University of Massachusetts, Lowell

Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman I, Bongers P, Amick B (1998) The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol 3:322–355

Koppes L, De Vroome E, Mol M, Janssen B, Van den Bossche S (2011) Nationale enquête arbeidsomstandigheden 2010: Methodologie en globale resultaten [The Netherlands working conditions survey 2010: Methodology and overall results]. TNO, Hoofddorp

Kristensen T, Borg V (2000) Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ). Nationale Institute of Occupational Health, Copenhagen

Lund T, Iversen L, Poulsen K (2001) Work environment factors, health, lifestyle and marital status as predictors of job change and early retirement in physically heavy occupations. Am J Ind Med 40:161–169

Nilsson K, Hydbom A, Rylander L (2011) Factors influencing the decision to extend working life or to retire. Scand J Work Environ Health 37:473–480

Proper K, Deeg D, Van der Beek A (2009) Challenges at work and financial rewards to stimulate longer workforce participation. Hum Resour Health. doi:10.1186/1478-4491-7-70

Romans F (2007) The transition of women and men from work to retirement. Eurostat Communities, Luxembourg

Schaufeli W, Van Dierendonck D (2000) Handleiding van de Utrechts Burnout Schaal (UBOS) [Manual of the Utrecht Burout Scale (UBOS)]. Swets & Zeitlinger, Lisse

Siegrist J, Wahrendorf M, von dem Knesebeck O, Jürges H, Börsch-Supan A (2007) Quality of work, well-being, and intended early retirement of older employees: baseline results from the SHARE Study. Eur J Public Health 17:62–68

Sijpersma R (2003) De oudere werknemer in de bouw [The older worker in the construction industry]. Economisch Instituut voor de Bouwnijverheid, Amsterdam

Szubert Z, Sobala W (2005) Current determinants of early retirement among blue collar workers in Poland. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 18:177–184

United Nations (2007) World economic and social survey 2007: development in an ageing world. United Nations. Department of economic and social affairs, New York

Van den Berg T, Schuring M, Avendano M, Mackenbach J, Burdorf A (2010a) The impact of ill health on exit from paid employment in Europe among older workers. Occup Environ Med 67:845–852

Van den Berg T, Elders L, Burdorf L (2010b) Influence of health and work on early retirement. J Occup Environ Med 52:576–583

Van den Bossche S, Koppes L, Granzier J, De Vroome E, Smulders P (2008) Nationale enquête arbeidsomstandigheden 2007: Methodologie en globale resultaten [The Netherlands working conditions survey 2007: Methodology and overall results]. TNO, Hoofddorp

Van Nimwegen N, Beets G (2006) Social situation observatory. Demography monitor 2005. Demographic trends, socioeconomic impacts and policy implications in the European Union. Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute, The Hague

Van Solinge H, Henksens K (2010) Living longer, working longer? The impact of subjective life expectancy on retirement intentions and behaviour. Eur J Public Health 20:47–51

Von Bonsdorff M, Huuhtanen P, Tuomi K, Seitsamo J (2010) Predictors of employees’ early retirement intentions: an 11-year longitudinal study. Occup Med (Lond) 60:94–100

Welch L, Haile E, Boden L, Hunting K (2008) Age, work limitations and physical functioning among construction roofers. Work 31:377–385

Welch L, Haile E, Boden L, Hunting K (2009) Musculoskeletal disorders among construction roofers–physical function and disability. Scand J Work Environ Health 35:56–63

Ybema J, Geuskens G, Oude Hengel K (2010) Oudere werknemers en langer doorwerken [Older employees and prolonging working life]. TNO, Hoofddorp

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oude Hengel, K.M., Blatter, B.M., Geuskens, G.A. et al. Factors associated with the ability and willingness to continue working until the age of 65 in construction workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 85, 783–790 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-011-0719-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-011-0719-3