Abstract

Purpose

It is questionable whether the Maslach Burnout is suitable for studying burnout prevalence in preclinical medical students because many questions are patient-centered and the students have little or no contact with patients. Among factors associated with burnout in medical students, the gender shows conflicting results. The first aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of the risk of burnout in medical students in preclinical and clinical years of training, using the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey, specifically designed and validated to assess the burnout in university students, and secondly, to investigate the association between gender and burnout subscales.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was carried out in a sample of 270 Spanish medical students—176 (65%) in the third year and 94 (35%) in the sixth year of training—using the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey questionnaire.

Results

Internal consistencies (Cronbach’s alpha) for the three subscales on the whole sample were as follows: for exhaustion 0.78, cynicism 0.78, and efficacy 0.71. Moreover, the prevalence of burnout risk was significantly higher in sixth-year students 35 (37.5%) compared with students in third year of training 26 (14.8%) (χ2 test, p < 0.0001). No significant association was found between gender and burnout subscales.

Conclusions

The Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey overcame difficulties encountered when students have little or no contact with patients. Our findings show that the risk of burnout prevalence doubled from the third year to sixth year of training and that gender was not significantly associated with any of the subscales of burnout.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

To date, there is not a general accepted definition of burnout, but the most common definition was offered by Maslach (1993): “a psychological syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment that can occur among individuals who work with other people in some capacity”.

The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) is the most commonly used instrument for measuring burnout. Given the increasing interest in burnout within occupations that are not so clearly people-oriented, a general version of the MBI was developed: the MBI-General Survey (MBI-GS) (Schaufeli et al. 1996). Here, the three components of the burnout construct are conceptualized in slightly broader terms, taking into consideration the job itself rather than personal relationships associated with the job. The MBI-GS has three subscales parallel to those of the MBI: exhaustion, cynicism, and professional effectiveness. Of these subscales, the one that differs from the original MBI is the introduction of cynicism instead of depersonalization. Depersonalization is the quality of burnout that was most exclusively associated with human service work. Cynicism reflects indifference or distant attitude toward work (Schaufeli et al. 1996). From the MBI-GS version (16 items) (Schaufeli et al. 1996) the MBI-GS Spanish version (15 items) arises after removing one particular cynicism item “I just want to do my work and not be bothered”, because it was shown to be ambivalent and thus unsound (Schaufeli et al. 2002a, b; Schutte et al. 2000). From the MBI-GS Spanish version (15 items) the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey emerges, which has been adapted to be used among university students. For example, the item “I feel emotionally drained from my work” was changed to “I feel emotionally drained by my study” (Schaufeli et al. 2002a). All versions of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) meet the requirements of adequate factorial validity and internal consistency to estimate the burnout syndrome (Maslach et al. 1996; Schaufeli et al. 2002a, b; Schutte et al. 2000). All MBI versions can be considered as a screening measure that identifies the people at risk of developing burnout, but they cannot be used to “diagnose” burnout without clinical criteria (Maslach et al. 1996).

Studies on the prevalence of burnout in medical residents and practicing physicians are abundant, and research on medical student burnout is increasing in the last years and most of the studies have focused upon the clinical years, but a few have focused in the preclinical years. Looking into perspective these reports and reviews, the results are like a “ladder” and the preclinical years students are placed in the first step with the lowest prevalence. The reported prevalence showed a wide range from 2 to 76% depending on the definitions and criteria used, samples studied, and cutoff points applied: preclinical students from 2 to 53% (Guthrie et al. 1997, 1998; Dyrbye et al. 2006; Dahlin and Runeson 2007; Santen et al. 2010); clinical students from 10 to 45% (Guthrie et al. 1997; Willcock et al. 2004; Dyrbye et al. 2006; Dahlin and Runeson 2007; Dahlin et al. 2007; Santen et al. 2010); medical residents from 27 to 75% (Martini et al. 2004; Thomas 2004; Prins et al. 2007; IsHak et al. 2009); and practicing physicians from 25 to 60% (Escriba-Agüir et al. 2006; Soler and Yaman 2008; Shanafelt et al. 2009).

The standard tool used to measure burnout was MBI-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) with the exception of four studies conducted in preclinical medical students. Three of them in Europe, Guthrie et al. (1997, 1998) used a modified version of MBI-HSS, and Dahlin et al. (2007) applied the student version of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI) (Halbesleben and Demerouti 2005), and one in the United States by Santen et al. (2010) who used an adapted version of MBI-HSS. Specifically, Santen et al. (2010) reported “the word “classmates” replaced “patient” in the preclinical version of the survey”, and Guthrie et al. (1997, 1998) reported “so that questions about work were replaced by identical questions about the medical course”. In the first year of training, very few students completed the depersonalization and personal accomplishment subscales since many of the questions were not appropriate for preclinical students, as they were not involved in patient care.

Among demographic factors associated with burnout in medical students, the gender shows conflicting results: Willcock et al. (2004) reported that male students were significantly more depersonalized than female students, and Santen et al. (2010) found no significant association.

Several factors may contribute to burnout of medical students, including curricular factors, personal life events, and the learning environment (Dyrbye et al. 2006, 2009; Santen et al. 2010), and this leads to important consequences such as unprofessional conduct, increased risk of suicidal ideation, and serious thoughts of dropping out (Dyrbye et al. 2008, 2010a, b). However, there is good news that the burnout in medical students may be reversible, and approximately 26% of them can be recovered within a year (Dyrbye et al. 2008).

Given the difficulties outlined above to measure burnout in preclinical students due to little or no contact with the patient, and the discrepancies in relation to gender, they are the reasons to conduct this cross-sectional study with the following objectives: first, to investigate the prevalence of the risk of burnout, in a sample of medical students in third preclinical year and sixth clinical year of training at the School of Medicine of Seville, using the specifically designed and validated to assess the burnout in university students, and secondly, to investigate the association between gender and burnout subscales. In addition, this study will also be used as a baseline, previous to the implementation of the new curriculum adapted to the European Space of Higher Education, in which the total number of hours, including theory and practice over the 6 years of medical training will be increased from 4,575 to 9,000 h.

Method

Participants

All medical students of third year (last year of preclinical training) and sixth years (final year of clinical training) enrolled in the School of Medicine of Seville were invited to participate in this study on the first day of the course, when all students are present at the conference opening in their respective schedules and classrooms. The lecturer explained them that the reason of the study was a better knowledge of their academic status and asked for the cooperation of students. Participation was voluntary and the answers to the test anonymous. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the University of Seville.

Data collection

Questionnaires were distributed at the end of the lecture among the students who had agreed to participate, in the third or sixth year of training respectively, during the first term of 2008. The lecturer explained, again, the reason of the study. They were not informed about any of the hypotheses of the study. The questionnaires were collected after completion by the students. We collected limited demographic information to ensure the anonymity of the respondents and to encourage participation and honest reporting.

Measurement of burnout

Burnout was assessed in medical students of third and sixth year of training using the modified version of the MBI-GS (Schaufeli et al. 1996), slightly adapted for its use with university students, under the name of Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS). The MBI-SS consists of 15 items that constitute three subscales: exhaustion (EX; 5 items), cynicism (CY; 4 items), and efficacy (EF; 6 items). All items are scored on a 7-point frequency rating scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (every day).

Finally, scores of each dimension of burnout are obtained by performing arithmetic means of individual items making up each dimension of burnout. According to normative data of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (Bresó et al. 2007), based on a sample of Spanish working population, the mean scores and standard deviations (SD) of the three subscales are exhaustion 2.12 (1.23), cynicism 1.50 (1.30), and the efficacy of 4.45 (0.9). The total score for each subscale is categorized “low”, “average”, or “high”, based on the lower, medium, and upper quartile of the score-distribution (Brenninkmeijer and Van Yperen 2003). Thus, the lower and upper quartile of each burnout dimensions are: EX ≤ 1.2 and ≥2.8; CY ≤ 0.6 and ≥2.25; EF ≤ 3.84 and ≥5.16. For our study, we defined burnout as a high score on the exhaustion or cynicism subscales. We did not include scores for the efficacy subscale, because it is the weakest burnout dimension in terms of significant relationships with other variables and plays a minor role in the burnout syndrome (Schaufeli 2003).

Statistical analysis

First, descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were used to analyze the data. Secondly, the internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for exhaustion, cynicism, and efficacy was conducted. It was followed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) to see whether there was any difference between groups on some variable. The comparison of categorical variables such as gender and years of training was performed using the Fisher or chi-square tests. The level of statistical significance was fixed equal or smaller of 0.05. All analysis were done using SPSS version 15.0.

Results

Out of 447 undergraduate students enrolled in the School of Medicine of Seville—231 in the third year, and 216 in the sixth year of training—270 (63%) of them agreed to participate. Response rates were 65% (176) among students in the third year, and 35% (94) in the sixth year of training. The age, gender, and ethnicity of all students enrolled in third and sixth course were quite similar to that shown by the responders. Demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. Internal consistencies (Cronbach’s alpha) for the three subscales of Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS) of the whole sample were satisfactory (α > 0.70) (Nunnaly and Bernstein 1994): exhaustion 0.78, cynicism 0.78, and efficacy 0.71.

The mean scores and standard deviations (SD) obtained in the total sample (men and women) for the exhaustion 2.10 (1.0), cynicism 0.95 (1.0), and the efficacy of 4.35 (0.83) were in the range of moderate score-distribution, in the middle quartile between the 25th and 75th percentiles. In the analysis of variance according to gender and year of training in the total sample, significant statistical differences were not found in any subscale.

Table 2 shows that 61 (22.6%) of the total sample were at risk of burnout. Forty-eight (17.8%) had high score in exhaustion, 27 (10%) in cynicism, and 48 (17.8%) in efficacy.

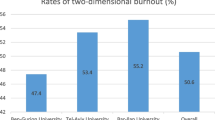

Table 3 shows that, given the training year, sixth-year students showed a significant increase in mean scores, number, and percentage of exhaustion and cynicism, and a significant decrease in mean scores, number, and percentage of efficacy compared to students in their third year of training. Moreover, the prevalence of burnout risk was significantly higher in sixth-year students 35 (37.5%) compared to students in the third year of training 26 (14.8%) (χ2 test, p < 0.0001).

Discussion

Up to now, the prevalence of the risk of burnout was unknown in medical students in Spain. Our results show that almost one in four medical students are at high risk of burnout and that prevalence of burnout risk doubled from third year to sixth year of training. They also show that there was no significant association between gender and burnout subscales.

Comparing our results with other reported in the literature is not an easy task, mainly due to three aspects: instruments and cutoff points used to measure burnout, the criteria used to define the burnout and, ultimately, the difference in curricula between the Schools of Medicine.

The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) is universally accepted as the standard for assessing burnout and has been used in studies of burnout in medical students (Guthrie et al. 1997, 1998; Willcock et al. 2004; Dyrbye et al. 2006, 2009, 2010a, b; Santen et al. 2010). Only Dahlin et al. (2007) have applied the student version of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI).

There is a considerable variability in how researchers have defined the burnout (Prins et al. 2007). Defining burnout as having a high score on both emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and a low score on personal accomplishment on the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) can result in an underestimation of burnout (Brenninkmeijer and Van Yperen 2003; Guthrie et al. 1997, 1998; Santen et al. 2010). Using a less conservative definition of burnout, as high scores on emotional exhaustion or depersonalization but not a low score on the personal accomplishment subscale (Willcock et al. 2004; Dyrbye et al. 2006), can result in an overestimation of burnout rates (Brenninkmeijer and Van Yperen 2003). There is also a third definition halfway between the aforementioned as high scores on exhaustion and disengagement (cynicism), used by Dahlin et al. (2007).

The last aspect is the difference in curricula among Schools of Medicine. There are significant differences in the demography of medical students from United States, Canada, and Australia (i.e, age at matriculation, preliminary bachelor degree) and in the curriculum of the United States and Canadian in clinical training with other Schools of Medicine (Dyrbye et al. 2006; Willcock et al. 2004; Santen et al. 2010). Students in the UK, Sweden, and Spain, in general, begin their medical studies without any preliminary higher education, usually at the age of eighteen or nineteen (Guthrie et al. 1997, 1998; Dahlin et al. 2007). Furthermore, for example, in the School of Medicine of Seville, although clinical practice has been introduced in medical schools, allowing students rotate between each clinical department every few weeks in the sixth year of training, students have actually been relegated to a bystander role and are not allowed to participate directly in providing patient care.

It is questionable whether the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (HSS) is a useful instrument to measure burnout at the early stages of medical training, as so many questions are focused on patients and students have relatively little contact with them (Guthrie et al. 1997). In fact, in MBI-HSS seven out of 22 items are related to patient care, belonging to the subscales of depersonalization and personal accomplishment. Santen et al. (2010) have recently reported “the word “classmates” replaced “patient” in the preclinical version of the survey”. Thus, Guthrie et al. (1998) reported in their article “the scores on the Maslach Burnout Inventory in first year students for the depersonalization and personal accomplishment subscales are not shown since very few students completed these subscales”. We tried to overcome the difficulties outlined above, applying the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS), specifically designed to assess the burnout in students, and in which were eliminated seven questions focused on the patient and therefore the BMI-SS only has 15 items. In addition, this instrument has been validated in samples of university students from different European countries, including Spain. The construct validity of MBI-SS has been identified by previous researchers (Schaufeli et al. 2002a, b; Schaufeli and Salanova 2007), and the criteria they used to validate the construct were the following: the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)/structural equation models (SEM), and the coefficient of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) with values above 0.72, indicating adequate internal consistency. The internal consistencies (Cronbach’s alpha) for the three subscales in our study were above 0.71.

Perhaps it could be argued that this instrument does not reflect the environment in which medical students are immersed, which is quite different from other university degrees. That is true, but when really the medical student is incorporated into that scenario is in years of clinical training when engaging in the direct care of patients. And of course, if they spend many hours daily in this task, then, the appropriate instrument would be the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS). But unfortunately, in our School of Medicine, this does not happen not even in the sixth year of training and that is why we have used also in these students the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS).

Given the above-mentioned, a relative comparison can be made with other reports. Our result showed an increasing prevalence of burnout and its subscales as students advance through training in medical school, and they are consistent with previous studies (Willcock et al. 2004; Dyrbye et al. 2006; Santen et al. 2010). However, Guthrie et al. (1997) and Dahlin and Runeson (2007) did not found significant rises. Moreover, our results support the hypothesis that burnout can occur during preclinical years of medical school (Dyrbye et al. 2006; Santen et al. 2010), with important implications such as age and years of training more appropriate to start screening and prevention.

In our study, gender was not significantly associated with burnout subscales, and previous studies show different results. Willcock et al. (2004) found that in the fourth year, male students were significantly more depersonalized than female students; however, in the last term of internship year, this association disappeared. Santen et al. (2010) found no significant relationship with burnout, and other researchers do not report information about this topic in their articles (Guthrie et al. 1997; Dahlin and Runeson 2007; Dyrbye et al. 2006). Regarding our negative result, one possible explanation may be that the majority of participants were women (70%), which adequately reflects trends at the medical schools over the last decades. Perhaps this recent trend has alleviated some of the pressures previously experienced by women to equal, and even outperform, their male counterparts in order to prove their worth in what were once male-dominated fields. In Table 4, we have tried to summarize the results of the articles referred to in the discussion, which shows the “high” scores on each dimension and the burnout rate among students.

However, our study has some limitations. First, this study is cross-sectional and therefore cannot determine causal relationships. Second, response rate in the sixth year of training was low and this could introduce bias into the results. A possible explanation could be that the interest of these students is lower as they progress through years of training, perhaps because education is too theoretical and they are already very close to finishing the medical career, or they are more committed to perform other tasks at the same time, as is the preparation of a state exam, called MIR (Medico Interno Residente), which is very demanding and required to access specialist training. In addition, burnout students may be less motivated to fill out a survey or that they would be more likely to participate because the topic is relevant to them. Third, since this study was based on a single institution, the results might not be representative of all students of Spain.

Our study has several important strengths. First, this is the first study to our knowledge about the risk of burnout in medical students conducted in Spain. Furthermore, our results provide some data to suggest the use of Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey to study the risk of burnout in preclinical years of training.

In conclusion, the prevalence of burnout risk doubled from the third year to sixth year of training supporting the hypothesis that burnout may appear during preclinical years of medical school with important implications such as age and years of training more appropriate to start screening and prevention. Gender was not significantly associated with any of burnout subscales at least in our cross-sectional study. Finally, the main reason for using the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS) has been the feature of our student population. Specifically, the MBI-SS allows overcome difficulties encountered when students have little or no contact with patients. However, further studies are needed to confirm these findings.

References

Brenninkmeijer V, Van Yperen N (2003) How to conduct research on burnout: advantages and disadvantages of a unidimensional approach in burnout research. Occup Environ Med 60:16–20

Bresó E, Salanova M, Schaufeli WB, Nogareda C (2007) Síndrome de estar quemado por el trabajo “Burnout” (III): instrumento de medición. Nota Técnica de Prevención, 732, 21ª Serie. Instituto Nacional de Seguridad e Higiene en el trabajo

Dahlin ME, Runeson B (2007) Burnout and psychiatric morbidity among medical students entering clinical training: a three year prospective questionnaire and interview-based study. BMC Med Educ 7:6–14

Dahlin M, Joneborg N, Runeson B (2007) Performance-based selfesteem and burnout in a cross-sectional study of medical students. Med Teach 29:43–48

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Huntington JL, Lawson KL, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD (2006) Personal life events and medical student burnout: a multicenter study. Acad Med 81:374–384

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Massie FS, Power DV, Eacker A, Harper W, Durning S, Moutier C, Szydlo DW, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD (2008) Burnout and suicidal ideation among US medical students. Ann Intern Med 149:334–341

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Harper W, Massie FS Jr, Power DV, Eacker A, Szydlo DW, Novotny PJ, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD (2009) The learning environment and medical student burnout: a multicentre study. Med Educ 43:274–282

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Power DV, Durning S, Moutier C, Massie FS Jr, Harper W, Eacker A, Szydlo DW, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD (2010a) Burnout and serious thoughts of dropping out of medical school: a multi-institutional study. Acad Med 85:94–102

Dyrbye LN, Massie FS Jr, Eacker A, Harper W, Power D, Durning SJ, Thomas MR, Moutier C, Satele D, Sloan J, Shanafelt TD (2010b) Relationship between burnout and professional conduct and attitudes among US medical students. JAMA 304:1173–1180

Escriba-Agüir V, Martin-Baena D, Perez-Hoyos S (2006) Psychosocial work environment and burnout among emergency medical and nursing staff. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 80:127–133

Guthrie E, Black D, Shaw C, Hamilton J, Creed F, Tomenson B (1997) Psychological stress in medical students: a comparison of two very different courses. Stress Med 13:179–184

Guthrie E, Black D, Bagalkote H, Shaw C, Campbell M, Creed F (1998) Psychological stress and burnout in medical students: a five year prospective longitudinal study. J R Soc Med 91:237–243

Halbesleben JRB, Demerouti E (2005) The construct validity of an alternative measure of burnout: investigating the English translation of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory. Work Stress 19:208–220

IsHak WW, Lederer S, Mandili C, Nikravesh R, Seligman L, Vasa M, Ogunyemi D, Bernstein CA (2009) Burnout during residency training: a literature review. JGME 1:236–242

Martini S, Arfken C, Churchill A, Balon R (2004) Burnout comparison among residents in different medical specialties. Acad Psychiatr 28:240–242

Maslach C (1993) Burnout: a multidimensional perspective. In: Schaufeli WB, Maslach C, Marek T (eds) Professional burnout: recent developments in theory and research. Taylor and Francis, New York, pp 20–21

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP (1996) Maslach burnout inventory, 3rd edn. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto

Nunnaly JC, Bernstein IH (1994) Psychometric theory, 3rd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Prins JT, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, Tubben BJ, Van der Heijden FM, Van de Wiel HB, Hoekstra-Weebers JE (2007) Burnout in medical residents: a review. Med Educ 41:788–800

Santen SA, Holt DB, Kemp JD, Hemphill RR (2010) Burnout in medical students: examining the prevalence and associated factors. South Med J 103:758–763

Schaufeli WB (2003) Past performance and future perspectives of burnout research. SAJIP 29:1–15

Schaufeli WB, Salanova M (2007) Efficacy or inefficacy, that’s the question: burnout and work engagement, and their relationships with efficacy beliefs. Anxiety Stress Coping 20:177–196

Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Maslach C, Jackson SE (1996) The Maslach Burnout Inventory: General Survey (MBI-GS). In: Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP (eds) The Maslach burnout inventory—test manual, 3rd edn. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, pp 19–26

Schaufeli WB, Martínez I, Marqués-Pinto A, Salanova M, Bakker A (2002a) Burnout and engagement in university students: a cross-national study. J Cross Cult Psychol 33:464–481

Schaufeli WB, Salanova M, González-Romá V, Bakker A (2002b) The measurement of burnout and engagement: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J Happiness Stud 3:71–92

Schutte N, Toppinen S, Kalimo R, Schaufeli WB (2000) The factorial validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS) across occupational groups and nations. J Occup Organ Psychol 73:53–66

Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ et al (2009) Burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons. Ann Surg 250:463–471

Soler JK, Yaman H, Esteva M et al. (European General Practice Research Network Burnout Study Group) (2008) Burnout in European family doctors: the EGPRN study. Fam Pract 25: 245–265

Thomas NK (2004) Residents’ burnout. JAMA 292:2880–2889

Willcock SM, Daly MD, Tennant CC, Allard BJ (2004) Burnout and psychiatric morbidity in new medical graduates. MJA 181:357–360

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Galán, F., Sanmartín, A., Polo, J. et al. Burnout risk in medical students in Spain using the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 84, 453–459 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-011-0623-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-011-0623-x