Abstract

Objective

To examine the extent and relative value of presenteeism and absenteeism and work-related factors affecting them among health care professionals.

Methods

Physicians and nurses estimated their hours of absenteeism and presenteeism during the last 4 weeks due to health reasons, and how much their work capacity had been reduced during their presenteeism hours. Socio-economic background, factors related to work and work conditions and possible chronic and acute diseases were solicited.

Results

Presenteeism was more common but indicated lower monetary value than absenteeism. Job satisfaction explained the probability and magnitude of presenteeism, but not absenteeism. Experience of acute disease(s) during the study period of 4 weeks significantly predicted the probability of both presenteeism and absenteeism.

Conclusions

Experience of presenteeism seemed to be common among health care workers, and it had significant economic value, although not as significant as absenteeism had.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Presenteeism has been estimated to cause even more productivity costs than absenteeism, particularly in the case of some diseases such as allergies and arthritis (Burton et al. 1999, 2002, 2004; Goetzel et al. 2004; Schultz and Edington 2007). Having a health problem is a strong determinant of presenteeism, but it is also associated with multiple personal and work-related factors (Aronsson and Gustafsson 2005; Aronsson et al. 2000; Dew et al. 2005; Escorpizo et al. 2007). Occupational groups with high sickness presenteeism have shown high sickness absenteeism and low monthly income, although physicians showed a combination of high income and high presenteeism (Aronsson et al. 2000).

People working in health care services have been shown to have increased risk of being at work when sick (Aronsson et al. 2000; Elstad and Vabø 2008; Forsyth et al. 1999; McKevitt et al. 1997). Different cultural and organisational factors have been the reasons for their decision not to take sick leave. Health care workers regard a substantial core of daily tasks as “must-do tasks” (Elstad and Vabø 2008). Barriers to sick leave among health care workers have included difficulty in replacement, the extent the work needs to be covered by the workers’ own efforts after the absence and attitudes towards their own health (Aronsson et al. 2000; Elstad and Vabø 2008; McKevitt et al. 1997).

Yet, there is no generally accepted best method for measuring presenteeism, and there is a lack of a standard metric for reporting presenteeism across studies (Beaton et al. 2009; Escorpizo et al. 2007; Goetzel et al. 2004; Mattke et al. 2007; Lofland et al. 2004; Schultz et al. 2009). Challenges involved in measuring presenteeism have been found to exceed those in measuring absenteeism, especially in non-manual knowledge-based jobs that do not have easily measurable output (Mattke et al. 2007). The economic consequences of both presenteeism and absenteeism have been measured using the human capital approach, where the value of an hour of absence or decreased work performance has been estimated on the basis of salary from the productivity point of view (Berger et al. 2003; Burton et al. 1999, 2002; Hemp 2004; Kessler et al. 2004; Mattke et al. 2007; Pauly et al. 2008). In some such estimates, presenteeism has accounted for 1.5 times more working time lost than absenteeism, and costs have been higher (Sainsbury report 2007; Stewart et al. 2003; Wynne-Jones et al. 2009). Human capital approach assumes that wages reflect workers’ marginal contribution to employer’s output and perfectly competitive labour market (Mattke et al. 2007), which hardly prevails in most cases. Another method for estimating the value of an hour lost due absenteeism or presenteeism could be a contingent valuation approach, where the opportunity cost of an hour to the worker is solicited (Donaldson 2001). This method produces monetary values for time estimates that are derived from the worker’s point of view. Substitution and finding replacements is difficult, and working pace can be intensive in health care work. Thus, salary-based hourly costs may not properly reflect the value of time assessed by health care workers themselves.

Aim

The aim of this study was to examine the extent and relative value of presenteeism and absenteeism and work-related factors affecting them among health care professionals.

Materials and methods

Altogether, 14 departments from Turku City Hospital, Turku University Hospital and Turunmaa Hospital were chosen for this study. The hospitals’ administrators were consulted, and the departments were chosen so that they represented various expected working paces. Altogether, 272 subjects worked in the selected departments: 212 nurses and 60 physicians. They formed the sample for this study. The Ethical Committee of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland gave its consent for implementation of the study.

An anonymous questionnaire form with a prepaid return envelope addressed to the researchers was distributed among the sample employees. At the beginning of the questionnaire, there was an account of the implementing organisations, the aim of the study, the sampling method, as well as an account of the voluntary nature of the study and the rights of the study subjects in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Additionally, the subjects were informed that only aggregate results would be reported, and no individual or department-specific information would be provided to employers.

The questionnaire was compiled to reveal health care workers’ opinions and views of their work and stress load, and the consequences of undone or partly completed tasks. The first part of the study questions covered socio-economic background followed by questions related to work and work conditions. The following variables were formed for the analyses: age in years, gender, major work status dichotomised as (0) physician and (1) nurse, working hours per week, work shifts as (0) one, (1) two or (2) three-shift work dichotomised as (0) other than one-shift work, (1) one-shift work, time worked in the current department calculated in months, number of persons working in the same department, as well as the number of colleagues in the department and whether the department dealt with emergency patients. The respondent’s possible chronic and acute diseases during the last 4 weeks were ascertained. These were used in the analyses as dichotomies—having one or more acute or chronic diseases—to control for the effect of health status on absenteeism and presenteeism.

Levels of working pace, pressure of work, job satisfaction, possibility to find substitutes for oneself if absent and the extent to which an employee’s work must be compensated by his or her own effort after the absence were all determined with separate 10-cm-long Visual Analogue Scales with endpoints at (0) Not at all and (100) Extremely (Table 1).

Absenteeism was measured as the number of hours the subject had not been at work during the last 4 weeks due to health reasons, when he/she had been scheduled to be present. Presenteeism was solicited as the number of hours during the last 4 weeks the subject had been at work despite feeling that he/she should not have been at work due to health reasons.

Using the 10-cm-long Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), the subjects gave an average estimate of how much their work capacity had been reduced during their presenteeism hours over the last 4 weeks. The left-hand endpoint was labelled as (0) Not at all, and the right-hand endpoint as (100) Extremely. The millimetre distance from the left-hand endpoint was used as a measure of average work capacity loss during presenteeism.

In the contingent valuation method, the respondents were asked how much they would be willing to contribute in order to get a defined utility. The subjects then considered their own values and economic status and evaluated their willingness. To determine the marginal value of time, the subjects were asked to assess the compensation they would be willing to accept if they were offered the hypothetical opportunity to work a 1-h-longer shift on their very next working day. Additionally, the subjects were asked to assess their willingness to pay for the hypothetical opportunity to have a 1-h-shorter work shift the very next working day. The marginal value of one h was analysed by using both willingness-to-accept and willingness-to-pay values as well as their arithmetic mean value. In the final analyses, the monetary value of an absenteeism hour was that obtained by using willingness-to-accept method. The monetary value of a presenteeism hour was determined as the hour value obtained using the willingness-to-accept method multiplied by the perceived average level of reduced work capacity during the last 4 weeks. The monetary values of both absenteeism and presenteeism for the preceding 4 weeks were computed.

Altogether, 171 subjects—137 were nurses (64.6%) and 32 physicians (53.3%)—returned acceptably filled-in questionnaires. Owing to the anonymous data collection, it was not possible to make comparisons between the respondents and non-respondents.

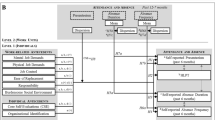

The chi-square test was used for statistical evaluation of proportions, and Student’s t-test was used for means. Logistic regression models were used to analyse the effect of each background variable on the probability of any presenteeism or absenteeism, while having the effects of other background variables simultaneously controlled. Linear regression models were fitted to study the effects of background variables on the magnitudes of presenteeism or absenteeism. The frequency distributions of both presenteeism and absenteeism were skewed to the right; thus, their close-to-normally distributed logarithmic transformations were used for the analyses. Both fixed and stepwise regression model methods were used.

Results

Altogether 37.4% had experienced presenteesim, i.e. they reported that during the preceding 4 weeks, they had gone to work despite the feeling that they should have taken sick leave. Their mean time at work when sick was 16.0 h. Their estimated average loss of working capacity during those hours was 45.4%. During the last 4 weeks, 23.4% of the subjects had been absent due to health reasons; the mean length of absence among them was 20.6 h.

The average overall monetary value of presenteeism for the 4-week period was 273.75 euros per person. Among those who had experienced presenteeism, the average value was 589.26 euros. The overall monetary value of absence due to health reasons was 373.87 euros per person, 196.52 euros among those who had not experienced presenteeism and 629.07 euros among those who had experienced presenteeism (P < 0.01).

Respondents who had been absent more hours due to health reasons had also experienced more hours of presenteeism (r = 0.248, P < 0.05) and had felt greater loss of working capacity while at work (r = 0.421, P < 0.01).

All work-related background factors had close-to-normal distribution. The more work pressure the respondents felt, the more hours they had worked when sick (r = 0.252, P < 0.01). In addition, the less job satisfaction they felt, the more the workers had worked when sick (r = −0.426, P < 0.01). Those who had experienced presenteeism during the last 4 weeks had shorter working experience and more often chronic and acute disease(s) (Table 1). In univariate analyses, only experience of acute disease(s) during the study period was significantly (P < 0.001) related to absenteeism. The effects of all other studied background variables were minor and statistically non-significant.

When the effects of the other studied background variables were simultaneously controlled, the probability of having experienced any presenteeism was significantly affected by a lower level of job satisfaction and occurrence of acute disease(s) (Table 2). Among those who had experienced presenteeism, a larger measure of presenteeism was significantly associated with a higher number of colleagues in the same department, a lower level of job satisfaction, having one-shift work and chronic disease(s). However, having experienced acute disease(s) during the last 4 weeks had an insignificant effect on the extent of experienced presenteeism (Table 3).

Absenteeism was also highly significantly more common among those who had experienced acute disease(s) and less common among one-shift workers than others (Table 2). However, the magnitude of absenteeism among those who had any was not significantly associated with any of the studied background variables (Table 3). Having experienced presenteeism was not significantly associated with the experience of any absenteeism or the magnitude of it.

Discussion

The Hospital District of Southwest Finland provides health care services for approximately 460,000 people residing in the area. The City of Turku Hospital, Turku University Hospital and Turunmaa Hospital are administrative units with altogether approximately 600 physicians and 1,700 nurses on their payrolls. The sampling was based on choosing departments from these hospitals that represented various working paces, as estimated by hospital administrators. All the physicians and nurses in these departments were included in the sample. However, one should be cautious when generalising the findings of this study directly to other settings, as working conditions vary.

It was assumed that the sample of workers was not biased and distorted, but represented the whole variety of physicians and nurses with varying lengths of working experience and varying working conditions. This was confirmed by the descriptive statistics of the sample (Table 1). However, owing to the relatively small final sample size collected from selected hospitals, and rather low response rate particularly among physicians, larger and probably more representative studies are needed to confirm the present findings. The selected departments included employees with very different working paces and pressures as well as those whose work was easy or very difficult to compensate. All these work-related background variables had close-to-normal distribution. The questionnaires were returned anonymously, and it was not possible to make analyses on the department level. Anonymity was seen necessary because some questions dealt with opinions of working conditions and experienced pressure at work. If the workers had been asked to indentify themselves somehow, the participation rate might have decreased and the reliability of the answers might have endangered. Our goal was to study how the employees themselves considered e.g. their work load and pace and how these are related to the perceived amount and level of presenteeism, which is also a highly subjective measure.

The time frame used influences the occurrence and magnitude of presenteeism. The longer the time frame, the more we can expect to have subjects who had experienced presenteeism; in earlier studies 26.3% when using ‘the last 7 days’ (Boles et al. 2004) and up to 88% when using ‘ever’ time frames (McKevitt et al. 1997). However, as the time frame stretches, the role of recall bias increases also. We expected that with the 4-week time frame chosen for this study, we should be able to have enough subjects with health-related presenteeism, while the subjects should still be able to quite reliably recall their working experiences. Prolonging the time frame up to 1 year would undoubtedly have increased the difficulty of remembering the hours of presenteeism and particularly the level of working capacity. Presenteeism has been shown to have significant predictive value for future absenteeism, also when adjusted for previous sick leaves, health status, demographics, lifestyle and work-related factors (Bergström et al. 2009a). However, the time frame of 4 weeks was too short to show if experience of presenteeism was associated with increased absenteesim.

Among health care workers, the relative value of absenteeism seemed to be higher than that of presenteeism, which is contradictory to earlier estimates of the roles of absenteeism and presenteeism for selected health conditions (Burton et al. 1999, 2002; Goetzel et al. 2004; Schultz et al. 2009; Stewart et al. 2003). Cost estimates for presenteeism have been suggested to be based on the so-called human capital approach, either salary conversion or productivity loss estimates on the business or firm level (Berger et al. 2003; Mattke et al. 2007; Schultz et al. 2009). However, level of income may not adequately represent the marginal value of time to the subjects. There are several reasons why an average hourly salary level does not reflect the value the workers themselves place on their time. Those with plenty of work and hectic working pace may value an extra hour of leisure time far higher than those with less busy schedule. Also, subjects in higher income levels are not as much in need for additional incomes as those with less income. Our method of valuing both absenteeism and presenteeism was based on the opportunity cost of an extra hour. The marginal value each subject was willing to accept as compensation for an extra working hour depends on both the value of his/her leisure time and the value of extra earnings. According to economic theory, subjects who value leisure time higher would demand higher compensation in order to be willing to give up leisure time. At the same time, those who are more in need of higher earnings would be more willing to forsake more leisure time for additional earnings. Using salary levels to indicate the value of hours present or absent from work would describe the values from the productivity point of view. However, using opportunity costs to the workers better represents the values the workers themselves set for their time.

One reason for the contradictory findings may also be the differences in legal, economic and social constraints and workplace cultures. All these factors change over time and vary between countries as well as workplaces. Health care workers may have different working traditions than some other professional groups, which may affect their attitudes towards absenteeism (Aronsson et al. 2000; McKevitt et al. 1997), and health care work has certain limitations for working when the worker expects the possibility to expose patients or co-workers to the danger of infection. Such working condition determinants may affect health care workers’ willingness to be absent or remain at work when feeling sick.

Although workers who had experienced presenteeism had felt a slightly higher working pace, more pressure at work, more difficulty in finding substitutes, and their work could not be compensated as easily as among those who had not experienced presenteeism, these work-related factors did not significantly influence the probability or the magnitude of either absenteeism or presenteeism. Our findings do not give employers any direct suggestion on how to modify working conditions in order to decrease the level of perceived presenteeism or hours of absenteeism. Also in a study by Hansen and Andersen (2008), work-related factors had more impact on presenteeism and absenteeism than did personal circumstances or attitudes, but the explanatory effect of these factors was relatively low. These findings are contradictory to some previous studies, suggesting that different work-related factors have been correlated to presenteeism (Aronsson et al. 2000; Aronsson and Gustafsson 2005; Böckerman and Laukkanen 2009; Caverley et al. 2007; McKevitt et al. 1997) and that presenteeism might be more sensitive than absenteeism to efforts to improve workplace health (Caverley et al. 2007) and working-time arrangements (Böckerman and Laukkanen 2009).

Presenteeism has been expected to be an independent risk factor of future poor health (Bergström et al. 2009b), and persistent presenteeism may lead to serious health issues in the long term (Kivimäki et al. 2005). Presenteeism and absenteeism are often inter-related (Schultz and Edington 2007), and attempts to successfully reduce absence may sometimes happen only at the expense of a rise in presenteeism (Koopmanschap et al. 2005). Different health problems have been associated with absenteeism than with presenteeism (Boles et al. 2004), but self-reported health problems have been highly similar (Caverley et al. 2007). In our study, chronic diseases included several conditions that may not have direct influence on the ability to work in any given 4-week period. Diseases like diabetes and elevated blood pressure may have been diagnosed even a long time ago, but have been kept under control with medication. Our present data size allowed dichotomised analyses of chronic diseases, but was too small for reasonable analyses of separate diagnostic groups. The duration of acute diseases is relatively short, which explains the finding that the presence of an acute disease increased the probability of experiencing presenteeism, but did not influence its magnitude.

Conclusion

Experience of presenteeism seemed to be common among health care workers, and it had significant economic value, although not as significant as absenteeism had.

References

Aronsson G, Gustafsson K (2005) Sickness presenteeism: prevalence, attendance-pressure factors, and an outline of a model for research. J Occup Environ Med 47:958–966

Aronsson G, Gustafsson K, Dallner M (2000) Sick but yet at work. An empirical study of sickness presenteeism. J Epidemiol Community Health 54:502–509

Beaton D, Bombardier C, Escorpizo R, Zhang W, Lacaille D, Boonen A, Osborne RH, Anis AH, Vibeke Strand C, Tugwell PS (2009) Measuring worker productivity: framework and measures. J Rheumatol 36:2100–2109

Berger ML, Howell R, Nicholson S, Sharda C (2003) Investing in healthy human capital. J Occup Environ Med 45:1213–1225

Bergström G, Bodin L, Hagberg J, Aronsson G, Josephson M (2009a) Sickness preseneteeism today, sickness absenteeism tomorrow? A prospective study on sickness presenteeism and future sickness absenteeism. J Occup Environ Med 51:629–638

Bergström G, Bodin L, Hagberg J, Lindh T, Aronsson G, Josephson M (2009b) Does sickness presenteeism have an impact on future general health? Int Arch Occup Environ Health 82:1179–1190

Böckerman P, Laukkanen E (2009) What makes you work when you are sick? Evidence from a survey of workers. Eur J Public Health 1–4

Boles M, Pelletier B, Lynch W (2004) The relationship between health risks and work productivity. J Occup Environ Med 46:737–745

Burton WN, Conti DJ, Chen C-Y, Schultz AB, Edington DW (1999) The role of health risk factors and disease on worker productivity. J Occup Environ Med 41:863–877

Burton WN, Conti DJ, Chen C-Y, Schultz AB, Edington DW (2002) The economic burden of lost productivity due to migraine headache: a specific worksite analysis. J Occup Environ Med 44:523–529

Burton WN, Pransky G, Conti DJ, Chen C-Y, Edington DW (2004) The association of medical conditions and presenteeism. J Occup Environ Med 46:S38–S45

Caverley N, Cunningham JB, MacGregor JN (2007) Sickness presenteeism, sickness absenteeism, and health following restructuring in a public service organization. J Manag Stud 44:304–319

Dew K, Keefe V, Small K (2005) ‘Choosing’ to work when sick: workplace presenteeism. Soc Sci Med 60:2273–2282

Donaldson C (2001) Eliciting patients’ values by use of ‘willingness to pay’: letting the theory drive the method. Health Expect 4:180–188

Elstad JI, Vabø M (2008) Job stress, sickness absence and sickness presenteeism in Nordic elderly care. Scand J Public Health 36:467–474

Escorpizo R, Bombardier C, Boonen A, Hazes JMW, Lacaille D, Strand V, Beaton D (2007) Worker productivity measures in arthritis. J Rheumatol 34:1372–1380

Forsyth M, Calnan M, Wall B (1999) Doctors as patients: postal survey examining consultants and general practitioners adherence to guidelines. Br Med J 319:605–608

Goetzel RZ, Long SR, Ozminkowski RJ, Hawkins K, Wang S, Lynch W (2004) Health, absence, disability, and presenteeism cost estimates of certain physical and mental health conditions affecting US employers. J Occup Environ Med 46(4):398–412

Hansen CD, Andersen JH (2008) Going ill to work–What personal circumstances, attitudes and work-related factors are associated with sickness presenteeism? Soc Sci Med 67:956–964

Hemp P (2004) Presenteeism: at work—but out of it. Harv Bus Rew October:49–58

Kessler RC, Ames M, Hymel PA et al (2004) Using the World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) to evaluate the indirect workplace costs of illness. J Occup Environ Med 46:S23–S37

Kivimäki M, Head J, Ferrie JE, Hemingway H, Shipley MJ, Vahtera J, Marmot MG (2005) Working while ill as a risk factor for serious coronary events: the Whitehall II study. Am J Public Health 95:98–102

Koopmanschap M, Burdorf A, Jacob K, Meerding WJ, Brouwer W, Severens H (2005) Measuring productivity changes in economic evaluation. Setting the research agenda. Pharmacoeconomics 23(1):47–54

Lofland J, Pizzi L, Frick KD (2004) A review of health-related workplace productivity loss instruments. Pharmacoeconomics 22(3):165–184

Mattke S, Balakrishnan A, Bergamo G, Newberry SJ (2007) A review of methods to measure health-ralated productivity loss. Am J Manag Care 13:211–217

McKevitt C, Morgan M, Dundas R, Holland WW (1997) Sickness absence and ‘working through’ illness: a comparison of two professional groups. J Public Health Med 19(3):295–300

Pauly MV, Nicholson S, Polsky D, Berger ML, Sharda C (2008) Valuing reductions in on-the-job illness: ‘Presenteeism’ from managerial and economic perspectives Health Econ 17:469–485

Schultz AB, Edington DW (2007) Employee health and presenteeism: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil 17:547–579

Schultz AB, Chen C-Y, Edington DW (2009) The cost and impact of health conditions on presenteeism to employers. Pharmacoeconomics 27:365–378

Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Morganstein D (2003) Lost productive work time cost from health conditions in the United States: results from the American productivity audit. J Occup Environ Med 45:1234–1246

The Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health (2007) Mental health at work: developing the business case. Report No.: policy paper 8

Wynne-Jones G, Buck R, Varnava A, Phillips C, Main CJ (2009) Impacts on work absence and performance: what really matters? Occup Med 59:556–562

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the research funds of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rantanen, I., Tuominen, R. Relative magnitude of presenteeism and absenteeism and work-related factors affecting them among health care professionals. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 84, 225–230 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-010-0604-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-010-0604-5