Abstract

Objectives: This study was undertaken to examine the association between sickness absence in Japanese employees and job demand/control and occupational class as psychosocial work characteristics. Methods: The study was cross-sectional in design with data collected from 20,464 male and 3,617 female employees, whose mean age was 40.9 years (SD ± 9.1 years) and 36.9 years (SD ± 10.8 years), respectively. The participants were asked to write the total number of sick leaves they had taken during the past year, and a comparison was made between the group with more than 6 days of sickness absence and the group with 0–6 days as a reference group. Job demands, job control, and worksite support from supervisors and colleagues were analyzed by the Job Content Questionnaire, and likewise by the Generic Job Stress Questionnaire of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Results: Both low job control and low support at the worksite were associated with a high frequency of sickness absence. But there was no clear relationship between job demands and sickness absence. The lowest sickness absence rate was found in male managers and the highest in male and female laborers. Conclusion: This is the first report of a large-scale survey of Japanese employees to show a high frequency of sickness absence associated with increased work stress and a socioeconomically low occupational class.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sickness absence at the workplaces is importantly related to low productivity and increased costs, and is related to the general health of employees. According to the Whitehall II, a cohort study of British civil servants, ill health was strongly associated especially with a longer spell of sickness absence (Marmot et al. 1995). The study of civil servants demonstrated that there was a clear association between medically certified sickness absence and mortality (Kivimäki et al. 2003), and a Finnish study also demonstrated a similar association (Vahtera et al. 2004a). They proposed that sickness absence could be used as a measure of health differentials in the working population even though sickness absence was influenced by multiple factors, including geographical, organizational, and personal ones (Searle 2003).

In Japan not many studies have been conducted on absence from work from the viewpoint of employee health. One of the reasons for this is that obtaining the complete data of employees’ sick leaves is difficult, because they often take paid holidays within their rights instead of sick leaves even when they are really sick (Ogura et al. 1998). Another reason may be that the rate of absence from work in Japan is relatively low among OECD countries (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 1991). A Japanese study of eight companies of over 1,000 employees each showed that the mean of the frequency of sickness absence of more than 6 consecutive days was 3/100 person years (Muto et al. 1999). This figure was low compared with the mean frequency of sickness absence of more than 7 consecutive days in the Whitehall II study (North et al. 1993); 12/100 person years for males and 30/100 person years for females. Moreover, a comparison study between the Japanese employed at a manufacturing factory and the Whitehall II demonstrated that the incident rate of the first occurrence of more than 7 consecutive day sickness absence in Japan was lower than that in the United Kingdom (Morikawa et al. 2004).

In the meantime, it has been reported that sickness absence was influenced by various personal factors, such as gender, smoking, alcohol consumption, marital status, educational background, physical load, and social class (North et al. 1993; Niedhammer et al. 1998; Smulders and Nijhuis 1999; Voss et al. 2001). Besides, high work stress elucidated by Karasek’s job demand/control model as a psychosocial work characteristic had advanced effects not only on various disorders such as coronary heart disease and psychiatric and musculoskeletal problems but also on sickness absence. Previous studies on the relationship between job demand/control and sickness absence pointed out that low control and low support were the main risk factors of increased sickness absence even after adjustment for age, smoking, alcohol consumption, marital status, education and occupation (Niedhammer et al. 1998) or adjustment for smoking, alcohol consumption, and sedentary status (Vahtera et al. 2000).

On the other hand, although several studies in Japan reported that sickness absence was associated with various factors such as sense of coherence, health promotion programs, and overtime working (Nasermoaddeli et al. 2003; Shimizu et al. 2003, 2004), few Japanese studies can be found on the influence of job demand/control on sickness absence. In addition to this, some indexes related to the health of Japanese employees were different from those in the UK study showing a socioeconomic gradient. While the rates of obesity, smoking, and lack of exercise were the highest in the low employment grade workers in the British study, Japanese data showed that higher grade employees had higher body mass index, and that leisure time physical activity was less even in managers, professionals, and manual workers than in clerks and service workers (Martikainen et al. 2001; Takao et al. 2003).

This situation prompted us to examine the association between job demand/control model and sickness absence and also the association between occupational class and sickness absence by using the baseline data from a multi-site prospective study for the Japanese in order to elucidate the relationship between psychosocial work factors and health.

Methods

Nine companies or factories participated in the baseline study. They were a light metal factory, three electrical manufacturing factories, two steel products factories owned by the same company, a heavy-metal products factory, an automobile plant, and a car products factory. The methods of collecting data were slightly different from firm to firm. All the employees were invited to participate at four sites. All the workers undergoing an annual medical checkup were invited at three sites. At another site the participants were restricted to the males aged 35 and over who underwent the checkup. And at the remaining site participating subjects were limited to supervisors and managers. All the information about the baseline study was obtained from the self-administered questionnaires conducted from April 1996 to May 1998; 21,248 males, 3,745 females, and 111 of unknown gender aged from 18 to 72 years replied. The average response rate was 85.2%, ranging from 73 to 100%, with the exception of 47% at a steel products factory. Details are available in previous reports (Takao et al. 2003; Kawakami et al. 2004).

Sickness absence

The participants were requested to write the total number of sick leaves they had taken during the past year, and with 6 days being close to the 90th percentile of the total sick leave of the participants, a comparison was made between the group taking more than 6 days of sickness absence and the group taking 0–6 days as a reference group.

Psychosocial work characteristic

Job demands, job control, and worksite support from supervisors and colleagues analyzed by the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) (Kawakami et al. 1995) and likewise by the Generic Job Stress Questionnaire of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (GJSQ) (Haratani et al. 1993, 1996) were classified as equally as possible into tertiles. In addition, job strain was defined as the ratio of job demands divided by job control.

The GJSQ has been used as frequently as JCQ to evaluate psychosocial work characteristics in Japan (Kawakami and Haratani 1999; Nakata et al. 2004). Out of the 13 scales of job stressors of GJSQ, we selected four scales, i.e. quantitative workload as job demands, job control, support from supervisors, and support from colleagues, which are composed of 11 items, 16 items, 4 items, and 4 items, respectively. Questions were scored on a Likert scale of 1–5 and the possible ranges of the scores were 11–55 in job demands, 16–80 in job control, 4–20 in support from supervisors, and 4–20 in support from colleagues.

Occupational class

We classified occupations into nine categories: eight categories assessed by ILO (International Labour Office Staff 1991), i.e. managers, professionals, technicians, clerks, service workers, skilled workers, machine operators and laborers, and an additional category for the other occupations. As the number of female managers was only five, we included the female managers in the professional group.

Other personal characteristics as confounding factors

The personal factors we adopted as possible covariates were categorized as follows. Smoking habit was divided into non-smoking or current smoking. Alcohol consumption was calculated in terms of ethanol volume consumed per week: none, 175 g and less, 176–350, 351–525, and 526 g and more. Marital status was divided into married, single, divorced, and widowed. Educational level was classified as ‘less than 12 years of education’, ‘12–15 years’, and ‘more than 15 years’. Cohabitation with children was asked about to determine the family status. Health status referred to current diseases and any history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, or other diseases including cardiovascular, digestive, hepatic, renal, musculoskeletal, malignant neoplasms, and psychiatric problems. Anyone having any one of these diseases was classified into the “disease” group.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were undertaken using the SAS program package, and males and females were analyzed separately. The differences of sickness absence in terms of age and occupational classes were determined by χ 2 test. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to estimate the odds ratios of sickness absence according to both psychosocial work characteristics and occupational classes after adjustment for age, smoking, alcohol consumption, marital status, educational level, cohabitation with children, history of disease as confounding factors, and companies as well because of the different constituents of the participants among companies. The subjects in this study were limited to the full-time employees up to 60 years of age. No statistical change in the result was observed even when we filled in the blanks of JCQ and GJSQ with the mean values.

Results

Valid data of sickness absence were obtained from 20,464 males and 3,617 females, whose mean age was 40.9 years (SD ± 9.1 years) and 36.9 years (SD ± 10.8 years), respectively. Frequencies of sickness absence for four age groups are shown in Table 1. The frequency of sickness absence was the highest for the 31–40 year-old male group and for the 51–60 year-old female group. No significant trend toward increased frequency with advanced age was recognized. The frequencies were higher for females than for males with the exception of the 31–40 year-old group.

The correlation coefficients between the scores of JCQ and GJSQ in terms of psychosocial work characteristics were 0.53 for job control, 0.65 for job demands, 0.56 for support from supervisors, and 0.40 for support from colleagues in males, and 0.40, 0.66, 0.56, and 0.40, respectively, in females. Table 2 shows the odds ratios of sickness absence according to the potential confounding factors. Current smokers, divorced or diseased people showed higher rates of sickness absence, while people who drink less or live with children showed lower rates. Males with a lower level of education showed a higher rate of sickness absence, while in females the highest level of education was related to a higher rate but not statistically significantly so.

Table 3 shows the odds ratios of sickness absence according to psychosocial work characteristics. In males, increased job control and support from supervisors and colleagues were significantly associated with lower sickness absence in both JCQ and GJSQ, with the exception that the association between support from colleagues and sickness absence in GJSQ was not significantly correlated. With increased job strain, sickness absence escalated. Regarding job demands, only the high job demand in GJSQ was significantly associated with decreased sickness absence. No significant change in the trend was noted other than slight attenuation of the associations after adjustment for possible confounders. The associations were similar in females although they lacked statistical power. But the association between support from supervisors and sickness absence in GJSQ was not as clear as that in JCQ, while in contrast the association between job strain and sickness absence in GJSQ was clearer.

There were no significant interactions between job strain and the supervisors’ support or the colleagues’ support in either sex.

In Table 4, the frequency of sickness absence in terms of occupational classes was the highest for laborers of both sexes, and was the lowest for male managers and for female service workers.

Table 5 shows the odds ratios of sickness absence according to the occupational classes with professionals as the reference group. In males, the odds ratio in managers was lower than that in professionals, whereas the odds ratio in laborers was higher than that in professionals. No significant difference was noted in the associations among the occupational classes even after psychosocial work characteristics by JCQ were taken into account. Furthermore, there was no significant change when GJSQ was used instead of JCQ (results not shown). In females, laborers also showed the highest odds ratio, though the difference was not statistically significant.

Discussion

We revealed that even after adjustment for several potential confounding factors, both high level of job strain induced by low job control and low level of support at the worksite were associated with an increased number of employees taking more than 6 days of sick leave in 1 year.

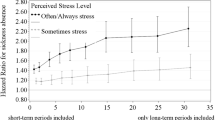

Incidentally, the relationship between short spells of sickness absence and health is controversial. A short spell of sickness absence for which no medical certificate was required did not strongly reflect predictive employees’ health (Vahtera et al. 2005). One-day absences were more frequent at the start and the end of a working week (Vahtera et al. 2001). Furthermore, the possibility of taking fake sick leaves without health problems could not be excluded. Therefore, we compared the group taking more than 6 days of sickness absence, which accounted for about the 90th percentile of the total sick leaves of the participants, with the group taking 0–6 days. In spite of its different categorization of the groups, the result of the present study is consistent with that of previous researches. Decreases in job demands, job control, and worksite support were related to a high rate of more than 7 consecutive days of sickness absence in the Whitehall II study (North et al. 1996). A 1-year follow-up of the Gazal study with 12,555 participants from the national electricity and gas company in France reported that low level of job control for both sexes and low level of worksite support for males were associated with an increased number of cases with more than 7 consecutive days of sickness absence. But, job demands showed no statistically significant relationship with sickness absence (Niedhammer et al. 1998). Additionally, the 6-year cohort study of the same population also demonstrated that low job control for both sexes and low worksite support for males predicted a higher incidence of 8–21 days of sickness absence (Melchior et al. 2003).

In addition, neither JCQ nor GJSQ questionnaire altered the result much. The correlations of psychosocial work factors between JCQ and GJSQ ranged from moderate to slightly high. However, we have found no study on sickness absence by GJSQ so far, and so we think GJSQ can also be used to elucidate the relationship between work characteristics and sickness absence.

Regarding sickness absence among different occupational classes, we found the lowest rate of sickness absence in male managers and the highest in both male and female laborers. The result shows some similarity with some European studies in that sickness absence increased with lower occupational classes (North et al. 1993; Niedhammer et al. 1998; Westerlund et al. 2004), but the occupational gradient of sickness absence of this study was small compared with that of European studies. This trend in this study did not change much after adjusting for confounding factors including health status, though we admit that for the cross-sectional study we cannot exclude the healthy worker effect, namely that people in the higher occupational classes are healthier to begin with. Besides, the difference in sickness absence rates among various occupational classes diminished after adjustment for job demands/control and support at the worksite, but with a statistically significant difference remaining in males. Therefore, we think that the socioeconomic gradient with regard to sickness absence also exists in Japan though it may not be as marked as in European countries.

In two Gazal cohort studies for the French (Niedhammer et al. 1998; Melchior et al. 2003) and a cohort study for the Belgians (Moreau et al. 2004) the relationship between psychosocial work characteristics and sickness absence did not change after adjustment for personal characteristics including occupational classes. Similarly, our study recognized no meaningful change in the relationship between psychosocial work characteristics and sickness absence even when occupational classes were taken into account.

This relationship, however, diminished after adjusting for employment grade instead of occupational classes in the Whitehall II study (North et al. 1996). This may be because the target subjects in the Whitehall II study were all civil servants—namely typical white-collar workers—whose employment grades markedly reflected the socioeconomic status linked up with hierarchy, income and educational background and other factors. On the other hand, the subjects of our study and the Gazal study were composed of blue and white-collar employees. Therefore, it might be possible that occupational classes did not sufficiently reflect confounding factors, e.g. physical load at work.

The present study demonstrated that the association between psychosocial work characteristics and sickness absence in females was weaker than that in males. Other psychosocial factors such as work–family interaction seemed to have a great influence on health and sickness absence in females. In fact, it was reported that in young dual-income Japanese 83% of working females did more than half of the household chores while 71% of working males entrusted other family members with housework (Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare 2004).

There are some limitations in this study that should be noted. First, since all information was obtained by self-administered questionnaires, several factors may have contributed to misclassification, e.g. difficulty with remembering the exact total days of sickness absence. Second, we failed to assess the characteristics of nonresponders, thereby not completely avoiding selection bias. The response rate of one company was low at 47%. However, whether or not the company’s data were reviewed did not affect the statistical result. In addition to this, differences among the companies did not affect the results. Third, for the cross-sectional design we did not investigate circumstantial changes in each company that might influence sickness absence, e.g. downsizing or expansion of the organization (Vahtera et al. 2004b; Westerlund et al. 2004). Additionally, all the companies were involved in manufacturing and had relatively big capital.

We studied the influence of job demand/control model as psychosocial work characteristics on sickness absence for the first time in Japan with the data from a large number of respondents working for multiple Japanese institutions. Both low job control and low support at the worksite were associated with a high frequency of more than 6 days of accumulated sick leaves during the previous year. Assessment of job demand/control by JCQ or GJSQ did not change the result much. Besides, we found the lowest sickness absence rate in male managers and the highest in laborers. Therefore, job control, support at the worksite and occupational status are also important psychosocial factors of occupational health in Japan that should be considered to promote workers’ and workplace health. The future direction of our study will be to elucidate the relationship between job demand/control and sick leaves including both short and long leaves by using the accurate attendance records preserved at Japanese workplaces, as compared with the corresponding European data.

Reference

Haratani T, Kawakami N, Araki S (1993) Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of NIOSH genetic job stress questionnaire. Jpn J Ind Health 35(Suppl):S214 (in Japanese)

Haratani T, Kawakami N, Araki S, Hurrell JJ Jr, Sauter SL, Swanson NG (1996) Psychometric properties and stability of the Japanese version of the NIOSH job stress questionnaire. In: Twenty-fifth international congress on occupational health. Book of Abstracts, Part 2, 393 pp

International Labour Office Staff (1991) International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-88). International Labour Office Staff, Geneva

Kawakami N, Haratani T (1999) Epidemiology of job stress and health in Japan: review of current evidence and future direction. Ind Health 37:174–186

Kawakami N, Kobayashi F, Araki S, Haratani T, Furui H (1995) Assessment of job stress dimensions based on the job demands-control model of employees of telecommunication and electric power companies in Japan: reliability and validity of the Japanese version of job content questionnaire. Int J Behav Med 2:358–375

Kawakami N, Haratani T, Kobayashi F, Ishizaki M, Hayashi T, Fujita O, Aizawa Y, Miyazaki S, Hiro H, Masumoto T, Hashimoto S, Araki S (2004) Occupational class and exposure to job stressors among employed men and women in Japan. J Epidemiol 14:204–211

Kivimäki M, Head J, Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Vahtera J, Marmot MG (2003) Sickness absence as a global measure of health: evidence from mortality in the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. BMJ 327:364–368

Marmot M, Feeney A, Shipley M, North F, Syme SL (1995) Sickness absence as a measure of health status and functioning: from the UK Whitehall II study. J Epidemiol Community Health 49:124–130

Martikainen P, Ishizaki M, Marmot MG, Nakagawa H, Kagamimori S (2001) Socioeconomic differences in behavioural and biological risk factors: a comparison of a Japanese and an English cohort of employed men. Int J Epidemiol 30:833–838

Melchior M, Niedhammer I, Berkman LF, Goldberg M (2003) Do psychosocial work factors and social relations exert independent effects on sickness absence? A six year prospective study of the GAZEL cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health 57:285–293

Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare (2004) White paper on the labor economy total contents. Gyosei Corporation, Tokyo (in Japanese)

Moreau M, Valente F, Mak R, Pelfrene E, de Smet P, De Backer G, Kornitzer M (2004) Occupational stress and incidence of sick leave in the Belgian workforce: the Belstress study. J Epidemiol Community Health 58:507–516

Morikawa Y, Martikainen P, Head J, Marmot M, Ishizaki M, Nakagawa H (2004) A comparison of socio-economic differences in long-term sickness absence in a Japanese cohort and a British cohort of employed men. Eur J Public Health 14:413–416

Muto T, Sumiyoshi Y, Sawada S, Momotani H, Itoh I, Fukuda H, Taira M, Kawagoe S, Watanabe G, Minowa H, Takeda S (1999) Sickness absence due to mental disorders in Japanese workforce. Ind Health 37:243–252

Nakata A, Haratani T, Yakahashi M, Kawakami N, Arito H, Kobayashi F, Araki S (2004) Job stress, social support, and prevalence of insomnia in a population of Japanese daytime workers. Soc Sci Med 59:1719–1730

Nasermoaddeli A, Sekine M, Hamanishi S, Kagamimori S (2003) Associations of sense of coherence with sickness absence and reported symptoms of illness in Japanese civil servants. J Occup Health 45:231–233

Niedhammer I, Bugel I, Goldberg M, Leclerc A, Guéguen A (1998) Psychosocial factors at work and sickness absence in the Gazel cohort: a prospective study. Occup Environ Med 55:735–741

North F, Syme SL, Feeney A, Head J, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG (1993) Explaining socioeconomic differences in sickness absence: the Whitehall II study. BMJ 306:361–366

North FM, Syme SL, Feeney A, Shipley M, Marmot M (1996) Psychosocial work environment and sickness absence among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Am J Public Health 86:332–340

Ogura K et al (1998) Surveillance study on sick leave system. Investigation research report no. 105. The Japan Institute of Labour, Tokyo (in Japanese)

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (1991) Absence from work reported in labour force surveys. The OECD Employment Outlook, OECD, France, chapt. 6, pp 177–197

Searle SJ (2003) Sickness absence. In: Waldron HA, Edling C (eds) Occupational health practice, chapt. 8, 4th edn. Arnold, London, pp 112–125

Shimizu T, Nagashima S, Mizoue T, Higashi T, Nagata S (2003) A psychosocial-approached health promotion program at a Japanese worksite. J UOEH 25:23–34

Shimizu T, Horie S, Nagata S, Marui E (2004) Relationship between self-reported low productivity and overtime working. Occup Med 54:52–54

Smulders PGM, Nijhuis FJN (1999) The job demands-job control model and absence behaviour: results of a 3-year longitudinal study. Work Stress 13:115–131

Takao S, Kawakami N, Ohtsu T, the Japan Work Stress, Health Cohort Study Group (2003) Occupational class and physical activity among Japanese employees. Soc Sci Med 57:2281–2289

Vahtera J, Kivimäki M, Pentti J, Theorell T (2000) Effect of change in the psychosocial work environment on sickness absence: a seven year follow up of initially healthy employees. J Epidemiol Community Health 54:484–493

Vahtera J, Kivimäki M, Pentti J (2001) The role of extended weekends in sickness absenteeism. Occup Environ Med 58:818–822

Vahtera J, Pentti J, Kivimäki M (2004a) Sickness absence as a predictor of mortality among male and female employees. J Epidemiol Community Health 58:321–326

Vahtera J, Kivimäki M, Pentti J, Linna A, Virtanen M, Virtanen P, Ferrie JE (2004b) Organisational downsizing, sickness absence, and mortality: 10-town prospective cohort study. BMJ 328:555–558

Vahtera J, Pentti J, Kivimäki M (2005) Sickness absence as a predictor of mortality among male and female employees. J Epidemiol Community Health 58:321–326

Voss M, Floderus B, Diderichsen F (2001) Physical, psychosocial, and organizational factors relative to sickness absence: a study based on Sweden Post. Occup Environ Med 58:178–184

Westerlund H, Ferrie J, Hagberg J, Jeding K, Oxenstiema G, Theorell T (2004) Workplace expansion, long-term sickness absence, and hospital admission. Lancet 363:1193–1197

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

The Japan Work Stress and Health Cohort Study Group

T. Haratani (National Institute of Industrial Health, Kawasaki, Japan)

F. Kobayashi (Aichi Medical University, Nagakute, Japan)

T. Hayashi (Hitachi Information & Telecommunication Systems, Ltd., Shinkawasaki Health Care Center, Kawasaki, Japan)

O. Fujita (Kariya General Hospital, Eastern Division, Kariya, Japan)

Y. Aizawa (Kitasato University School of Medicine, Sagamihara, Japan)

S. Miyazaki (Meiji University Law School, Tokyo, Japan)

H. Hiro (Adecco Health Support Center, Tokyo, Japan)

T. Masumoto (Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation, Kashima, Japan)

S. Hashimoto (Fujita Health University School of Medicine, Toyoake, Japan)

S. Araki (National Institute of Industrial Health, Kawasaki, Japan)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ishizaki, M., Kawakami, N., Honda, R. et al. Psychosocial work characteristics and sickness absence in Japanese employees. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 79, 640–646 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-006-0095-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-006-0095-6