Abstract

Background

A pilot study was conducted to evaluate the therapeutic results of intravitreal ganciclovir injection as a loading dose with or without the following oral valganciclovir for the treatment of cytomegalovirus (CMV) anterior uveitis in immunocompetent patients.

Methods

Six consecutive patients in whom active CMV anterior uveitis was detected by polymerase chain reaction assay of the aqueous humor were enrolled between January 2006 and December 2008. These patients received an intravitreal injection of ganciclovir (2 mg/0.05 ml) as a loading dose. Subsequent use of oral valganciclovir (900 mg twice a day) was determined according to the severity of the post-injection aqueous inflammation. Immune status and anterior chamber reaction of individual patients, visual acuity, intraocular pressure (IOP) at study entry, and follow-up intervals were examined.

Results

The mean patient-month follow-up period after intravitreal injection was 14.7 months (range, 12–22 months). Two patients received only the intravitreal ganciclovir injection once and four patients had received the following oral valganciclovir for average 2.3 months (range, 1–4 months). With this treatment strategy, the best-corrected visual acuity of the patients improved or stabilized; the IOP and the inflammation of anterior chamber of the patients were well controlled at all time points and there were no treatment-associated complications by the end of follow-up.

Conclusions

In patients with CMV anterior uveitis, intravitreal ganciclovir injection as a loading dose with or without the following oral valganciclovir can control the inflammation and IOP well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) can cause anterior uveitis in immunocompetent patients and has been identified recently as one of the disease entities in previously recognized idiopathic anterior uveitis [1–6]. The common clinical features of CMV anterior uveitis in immunocompetent patients are chronic, and/or recurrent uveitis with keratic precipitates complicated by elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) and the definite diagnosis can only be made by aqueous fluid analysis with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [1–6].

The previous literature on CMV anterior uveitis primarily consists of case reports and small case series, as this disease is fairly recently recognized [1–4, 6–8]. Therefore, the standard treatment has not yet been established. Ganciclovir or its prodrug valganciclovir is one of the effective drugs for CMV infections, including CMV hepatitis [9], retinitis [10], and encephalitis [11]. In the patients with anterior segment CMV infection, oral valganciclovir [5], intravenous ganciclovir [1], and topical ganciclovir [12] have been suggested to suppress the infection. The results, however, have been variable with some failure cases in each strategy. On the other hand, whether intravenous ganciclovir and oral valganciclovir have the ability of intraocular penetration across the blood-ocular-barrier into the aqueous humor in the eyes with CMV anterior uveitis remains to be elucidated. Here, we conducted a pilot study to evaluate the therapeutic results with a treatment strategy using intravitreal ganciclovir injection as a loading dose with or without the following oral valganciclovir in the patients with CMV anterior uveitis.

Materials and methods

This study was a prospective, interventional, consecutive case series of patients with CMV anterior uveitis, which was diagnosed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) at the Department of Ophthalmology, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou, Taiwan, between January 2006 and December 2008. Six eyes of six patients were included. The off-label use of intravitreal ganciclovir and its potential risks and benefits were discussed extensively with the patients before treatment. Exclusion criteria included history of hypersensitivity to ganciclovir, scleromalacia, and external eye infection at the injection site. The approval of the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and the informed consents of patients were obtained before treatment.

One patient was female and five patients were male. The mean age was 55.5 years (range, 32–72 years, Table 1). At least 100 μl of aqueous humor was obtained and sent for qPCR of herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella zoster virus (VZV), CMV, and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) by the method suggested by Stocher et al. [13]. As for CMV qPCR briefly, the viral DNA was extracted from the specimen using the High Pure Viral Nucleic Acid Kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) as described in the manual. The primers and probes for CMV detection were defined as GenBank accession numbers NC001347 (CMV-L-for 5′-GACACAACACCGTAAAGC-3′, CMV-L-rev 5′-CAGCGTTCGTGTTTCC-3′), which was documented to be highly conserved and specific for CMV [14]. The detection limit was reported as 250 virus-derived DNA copies per milliliter for CMV, with high sensitivity and specificity [13].

A 2 mg/0.05 ml amount of ganciclovir (Cymevene, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel Switzerland) was prepared from a new vial in the surgical room for each patient and placed in a tuberculin syringe using aseptic techniques right before injection. The drug was diluted with balanced salt solution (BSS, Alcon, Fort Worth, Texas, USA). After the eye was sterilized using 5% diluted povidone-iodine, an eyelid speculum was inserted to stabilize the eyelids. The injection of ganciclovir (2 mg/0.05 ml) was performed 3.5 to 4 mm posterior to the limbus, through the inferotemporal quadrant of pars plana with a 30-gauge needle under topical anesthesia. After the injection, visual acuity, IOP, blood pressure, and retinal artery perfusion were checked. The patients were prescribed with topical antibiotics for at least 7 days.

Patients were examined at 1 week and 1 month after the injection and at monthly appointments afterwards. Additional visits were arranged depending on the patient’s condition. Oral valganciclovir (Valcyte, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland) was prescribed as determined according to the severity of post-injection inflammation at the 1-week return visit. The CMV infection was considered controlled if the grading of the inflammation was less than 1+. Therefore, if the inflammation of the aqueous humor was less than 1+, we maintained the follow-up schedule without oral valganciclovir. If the inflammation was equal to or more than 1+, oral valganciclovir was prescribed (900 mg bid) for at least 1 month. The cessation of the oral valganciclovir was determined if the inflammation of the aqueous humor was less than 1+ at the following visit. Grading of the inflammation was performed as described by the SUN working group [15].

The age, sex, refraction, study entry, and interval best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) determined using Snellen E chart were recorded; the study entry and interval IOP determined by Goldmann applanation tonometry and intraocular inflammation activity were monitored. IOP equal to or more than 21 mmHg was considered high. Additional analyses including complete blood count with white blood cell differential count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, routine urinalysis, chest radiography, skin testing for tuberculin, syphilis serology, human leukocyte antigen B27, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serology, and CMV viral antigen in serum were ordered for all patients. The patients were also referred to internal medicine specialists for further evaluation if necessary.

The outcome variables recorded included BCVA, IOP, and aqueous inflammation grading. For comparison between two paired Gaussian groups, paired t-test was applied. All the visual acuity value was transformed from arithmetic scale into geometric scale (logMAR) before computation. All statistical tests were calculated using the SPSS software package for Windows, version 12.0 (SPSS Inc. Apache Software Foundation). A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Each patient was followed for a minimum of 12 months; the mean patient-month follow-up period was 14.7 months (range, 12–22 months). None of the enrolled patients had systemic immunodeficiency or detectable serum CMV antigen, and none had human leukocyte antigen B27 allele. One patient (patient 6) had diabetes. Every patient had a positive CMV aqueous qPCR and negative HSV, VZV, and EBV qPCR results. None of the patients had iris atrophy. Two patients (patients 1 and 3) received trabeculectomy and two patients (patients 4 and 5) had cataract extraction and intraocular lens implantation in other hospitals before CMV uveitis was definitely diagnosed. Two patients (patients 4 and 6) received only the intravitreal ganciclovir injection without the following oral valganciclovir dosage. Four patients had received the following oral valganciclovir for average 2.3 months (range, 1–4 months). Demographics and summary of the patients are listed in Table 1.

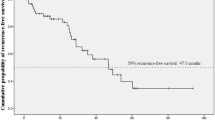

After the mean 14.7 patient-months (total 88 patient-months) follow-up, none of the study eyes had recurrent intraocular inflammation. On study entry, every enrolled patient had a high IOP in the affected eye. The mean study entry pre-injection IOP was 31.9 ± 5.0 mmHg (range, 24.3–38.1 mmHg). The interval postoperative IOP at 1, 3, 6, 9, 12 months were 12.3 ± 5.7, 11.0 ± 3.3, 10.6 ± 2.2, 11.8 ± 2.8, 12.3 ± 3.5, respectively (mean ± SD, mmHg; P = 0.003, <0.001, <0.001, <0.001, =0.001 respectively for 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months compared with study entry). IOP was statistically well controlled after the treatment strategy (Fig. 1); i.e., the IOPs, which had not been controlled by maximum of anti-glaucoma medication and/or surgery before diagnosis, could be medically controlled in every patient after the antiviral treatment strategy (Table 1). The mean study entry preoperative BCVA was 0.60 ± 0.25 (mean ± SD, logMAR units; 6/24, mean Snellen equivalent). The mean postoperative interval BCVA at 1, 3, 6, 9, 12 months were 0.40 ± 0.l5, 0.44 ± 0.15, 0.41 ± 0.14, 0.39 ± 0.13, 0.36 ± 0.12, respectively (mean ± SD, logMAR units; 6/15, 6/17, 6/15, 6/15, 6/14, respectively, mean Snellen equivalent; P = 0.04, 0.16, 0.11, 0.04, 0.03, respectively, for 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months) (Fig. 2). The mean interval BCVA at 3 and 6 months were worse than the study entry BCVA, but no significant difference was found, most likely because of sample size limitations. Twelve months after the treatment, all patients had an improved or stable vision (Fig. 3). There were no complications related to the treatment in the total patient-month interval.

Visual acuity expressed as Snellen for eyes of patients treated after the intravitreal loading injection of ganciclovir with or without the following oral valganciclovir. Values that appear on or above the diagonal line indicate stabilization or improvement in visual acuity after 12 months. It showed that the visual acuity of patients was improved or stable at 12 months

Case reports

Patient 4, a 61-year-old man had been receiving topical prednisolone intermittently since July 2007 for idiopathic anterior uveitis of his right eye. He received cataract extraction and intraocular lens implantation for the right eye in February 2005. At presentation, the BCVA was 6/15 and the IOP was 37.4 mmHg under anti-glaucoma medication. Slit-lamp examination revealed 2+ anterior chamber cells (Fig. 4a) under topical 1% prednisolone acetate every 3 hours. Fundoscopic examination demonstrated glaucomatous optic disc cupping. There were not contributory symptoms or signs in the left eye. Samples of aqueous humor tapping from the right eye were subjected to qPCR, and CMV DNA was detected. We performed intravitreal ganciclovir (2 mg/0.05 ml) injection within one week after tapping. The aqueous reaction became clear in one week (Fig. 4b). The BCVA improved to 6/8 and the IOP was 12.0 mmHg at 12- month follow-up. Oral valganciclovir had never been prescribed for this patient.

Patient 5, a 72-year-old woman had experienced ocular hypertension in her right eye for 20 months. She received an uneventful cataract extraction and intraocular lens implantation 1 year earlier. Anterior uveitis was diagnosed and topical corticosteroids were used off and on. The patient did not experience any eye pain.

The BCVA of her right eye was 6/20. Slit lamp revealed 2+ inflammation (Fig. 5a). High IOP (30 mmHg) was noted. CMV DNA was detected in the aqueous humor by qPCR. The intravitreal ganciclovir (2 mg/0.05 ml) was injected within 1 week after tapping. There was a 1+ level of aqueous inflammation 1 week later. She was treated with 2-month oral valganciclovir (900 mg twice daily); then, the aqueous cells subsided and valganciclovir was discontinued (Fig. 5b). The BCVA at 12 months was 6/15, and the IOP was 11.2 mmHg without using anti-glaucomatous drugs.

Patient 5. Clinical manifestations of cytomegalovirus anterior uveitis examined by slit-lamp biomiscroscopy. a Photograph showing anterior chamber cells (white arrows). b Photograph after intravitreal injection with ganciclovir and followed by 2 months of oral valganciclovir showed subsided anterior chamber inflammation

Discussion

This prospective study demonstrated the effects of intravitreal ganciclovir injection as a loading dose with or without oral valganciclovir as the following dosage to treat patients with CMV anterior uveitis. With this treatment strategy, the BCVA of the patients improved or stabilized; the IOP and the inflammation of anterior chamber of the patients were well controlled and there were no treatment-associated complications by the end of the follow-up. In addition, our results showed the intravitreal loading ganciclovir could decrease the duration of the following oral valganciclovir.

Corneal edema and glaucomatous optic nerve changes have been reported to be the common morbidity of CMV anterior uveitis when the infection has not been controlled well [1, 2, 12, 16–18]. The treatment strategy for CMV anterior uveitis, however, remains unsettled, because CMV anterior uveitis is an entity described only fairly recently. The treatment strategy and therapeutic results of previous studies are summarized in Table 2.

It has been suggested that a loading dosage is necessary for ganciclovir use in the suppression of CMV infection [9, 11, 19, 20]. A loading dose is useful for drugs that are toxic in the long run under high dosage. Such drugs need only a low maintenance dose to have the drug kept at the appropriate therapeutic level, but this also means that without an initial higher dose, it would take a longer time for the drug to reach that level within the body. Such long-term use at sub-therapeutic levels would facilitate the emergence of CMV mutations and resistance [19]. For the CMV central nervous system infection with a blood-organ barrier, which also exists intraocularly, Anduze-Faris et al. suggested a loading followed by maintenance therapy as the effective strategy [11]. In this study, we chose intravitreal ganciclovir (2 mg/0.05 ml), that has been reported to be safe and useful in CMV retinitis in immunocompromised patients [21], as the loading dose. Intravitreal ganciclovir may be more effective than systemic ganciclovir in patients with CMV anterior uveitis, presumably because of the establishment of a higher effective concentration at the site of infection. In the animal model, the vitreal concentration of ganciclovir after intravitreal injection was about 100 times higher than after intravenous injection [22]. In addition, intraocular local drug delivery could also decrease the side-effects of systemic ganciclovir-related bone marrow suppression and is also cost-effective.

Another unanswered question about the CMV anterior uveitis is how long treatment should be continued. In the previous two case series, in which fixed period of induction and maintenance treatments were conducted, high rate of the patients had recurrences within months after cessation of the treatment (Table 2) [1, 2]. Long-term therapy is recommended, especially facing any further relapses [2, 7, 8]. Van Boxtel et al. reported a patient had a recurrence immediately after discontinuation of oral valganciclovir, even after 1 year of treatment [5]. Hu reported that the duration of treatment should be extended if using oral valganciclovir for controlling CMV infection. However, extending the treatment duration increases the risk that the CMV will become resistant, which frequently occurs within 6 months as a result of progressive mutations in the CMV polymerase genes [23]. Besides, the higher cost of valganciclovir and its potential for renal and bone marrow toxicity [6] make it an unsuitable candidate for long-term therapy, especially in the under-developed or developing world. In our study, two patients received intravitreal ganciclovir injection only, and four patients were given the following oral valganciclovir for an average 2.3 months according to the response of the inflammation control after the initial intravitreal injection. With the treatment strategy, all the patients had resolution of the inflammation and no recurrences occurred in the mean 14.7 patient-month follow-up. Compared with previous studies, the duration of taking oral valganciclovir was shorter to prevent recurrences. Chee et al. treated three patients, who could not afford systemic therapy, with intravitreal ganciclovir 2 mg/0.1 ml weekly for 3 months; one patient had a recurrence, but the other two were well controlled. Compared to the use of systemic intravenous ganciclovir as a loading dose followed by oral anti-CMV medication (ganciclovir or valganciclovir) in the same article, the recurrence rate was less (1/3 vs. 8/9, Table 1) [1]. Koizumi et al. used topical 0.5% ganciclovir as a maintenance dose after a 2-week systemic ganciclovir treatment for the patients with CMV endotheliitis [12]. However, using high-performance liquid chromatography, Chee et al. reported that the topical ganciclovir could not reach an effective therapeutic level in the aqueous humor [1]. Thus, we suggest the loading regimen via intravitreal injection as appropriate for CMV uveitis and oral valganciclovir as the following dose based on the response of the inflammation control after the initial intravitreal injection.

It remains unclear why CMV anterior uveitis in immunocompetent patients has recently been recognized as a separate entity, whereas CMV can cause necrotic retinitis in immunocompromised or patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). This is probably because testing of anterior chamber fluid is not routinely performed in the patients with anterior uveitis and some patients with CMV anterior uveitis are diagnosed as Posner-Schlossman syndrome, Fuchs' heterochromic uveitis, or herpetic uveitis [24]. It has not been concluded whether the aqueous CMV virus is a new infection or a relapse from the silent infection. Since the CMV anterior uveitis is mostly seen in immunocompetent patients, our anti-viral treatment strategy may be not permanently curative, but rather temporarily halt progression of the disease. A long-term study is necessary and suggested to demonstrate the rate of relapse of aqueous inflammation when the intraocular concentration of the anti-viral drugs is decreased below the minimal inhibition concentration for the CMV viral particles.

This prospective study was limited by the small number of patients and the lack of a control group. Macular function might be further evaluated by microperimetry or multifocal electroretinogram, which were not available in our hospital. It has not been fully understood whether the CMV anterior uveitis is a disease of episodic or not. The long-term suppression of this disease remains to be elucidated.

In conclusion, loading dosage of ganciclovir may be an important key for anti-CMV treatment. Intravitreal ganciclovir as the loading dosage combined with oral valganciclovir, which was prescribed according to the severity of the post-injection inflammation index, may be a good treatment strategy for CMV anterior uveitis. Further long-term randomized and controlled studies should be performed to prove the effectiveness and safety of this treatment strategy.

References

Chee SP, Bacsal K, Jap A, Se-Thoe SY, Cheng CL, Tan BH (2008) Clinical features of cytomegalovirus anterior uveitis in immunocompetent patients. Am J Ophthalmol 145:834–840. doi:S0002-9394(07)01051-3 [pii] 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.12.015

de Schryver I, Rozenberg F, Cassoux N, Michelson S, Kestelyn P, Lehoang P, Davis JL, Bodaghi B (2006) Diagnosis and treatment of cytomegalovirus iridocyclitis without retinal necrosis. Br J Ophthalmol 90:852–855. doi:bjo.2005.086546 [pii] 10.1136/bjo.2005.086546

Hart WM Jr, Reed CA, Freedman HL, Burde RM (1978) Cytomegalovirus in juvenile iridocyclitis. Am J Ophthalmol 86:329–331

Teoh SB, Thean L, Koay E (2005) Cytomegalovirus in aetiology of Posner-Schlossman syndrome: evidence from quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Eye 19:1338–1340. doi:6701757 [pii] 10.1038/sj.eye.6701757

van Boxtel LA, van der Lelij A, van der Meer J, Los LI (2007) Cytomegalovirus as a cause of anterior uveitis in immunocompetent patients. Ophthalmology 114:1358–1362

Van Gelder RN (2008) Idiopathic no more: clues to the pathogenesis of Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis and glaucomatocyclitic crisis. Am J Ophthalmol 145:769–771. doi:S0002-9394(08)00146-3 [pii] 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.02.010

Mietz H, Aisenbrey S, Ulrich Bartz-Schmidt K, Bamborschke S, Krieglstein GK (2000) Ganciclovir for the treatment of anterior uveitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 238:905–909

Markomichelakis NN, Canakis C, Zafirakis P, Marakis T, Mallias I, Theodossiadis G (2002) Cytomegalovirus as a cause of anterior uveitis with sectoral iris atrophy. Ophthalmology 109:879–882. doi:S0161-6420(02)00961-2 [pii]

Winston DJ, Busuttil RW (2003) Randomized controlled trial of oral ganciclovir versus oral acyclovir after induction with intravenous ganciclovir for long-term prophylaxis of cytomegalovirus disease in cytomegalovirus-seropositive liver transplant recipients. Transplantation 75:229–233

Henderly DE, Freeman WR, Causey DM, Rao NA (1987) Cytomegalovirus retinitis and response to therapy with ganciclovir. Ophthalmology 94:425–434

Anduze-Faris BM, Fillet AM, Gozlan J, Lancar R, Boukli N, Gasnault J, Caumes E, Livartowsky J, Matheron S, Leport C, Salmon D, Costagliola D, Katlama C (2000) Induction and maintenance therapy of cytomegalovirus central nervous system infection in HIV-infected patients. AIDS (London, England) 14:517–524

Koizumi N, Suzuki T, Uno T, Chihara H, Shiraishi A, Hara Y, Inatomi T, Sotozono C, Kawasaki S, Yamasaki K, Mochida C, Ohashi Y, Kinoshita S (2008) Cytomegalovirus as an etiologic factor in corneal endotheliitis. Ophthalmology 115:292–297. doi:S0161-6420(07)00571-4 [pii] 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.04.053 e293

Stocher M, Leb V, Bozic M, Kessler HH, Halwachs-Baumann G, Landt O, Stekel H, Berg J (2003) Parallel detection of five human herpes virus DNAs by a set of real-time polymerase chain reactions in a single run. J Clin Virol 26:85–93

Gault E, Michel Y, Dehee A, Belabani C, Nicolas JC, Garbarg-Chenon A (2001) Quantification of human cytomegalovirus DNA by real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol 39:772–775

Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT (2005) Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol 140:509–516

Kim EC, Margolis TP (2006) Hypertensive iridocyclitis. Br J Ophthalmol 90:812–813. doi:90/7/812 [pii] 10.1136/bjo.2006.091876

Koizumi N, Yamasaki K, Kawasaki S, Sotozono C, Inatomi T, Mochida C, Kinoshita S (2006) Cytomegalovirus in aqueous humor from an eye with corneal endotheliitis. Am J Ophthalmol 141:564–565. doi:S0002-9394(05)01030-5 [pii] 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.09.021

Yamauchi Y, Suzuki J, Sakai J, Sakamoto S, Iwasaki T, Usui M (2007) A case of hypertensive keratouveitis with endotheliitis associated with cytomegalovirus. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 15:399–401. doi:783645110 [pii] 10.1080/09273940701486795

Boivin G, Gilbert C, Gaudreau A, Greenfield I, Sudlow R, Roberts NA (2001) Rate of emergence of cytomegalovirus (CMV) mutations in leukocytes of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome who are receiving valganciclovir as induction and maintenance therapy for CMV retinitis. J Infect Dis 184:1598–1602

De Clercq E (2004) Antiviral drugs in current clinical use. J Clin Virol 30:115–133

Young S, Morlet N, Besen G, Wiley CA, Jones P, Gold J, Li Y, Freeman WR, Coroneo MT (1998) High-dose (2000-microgram) intravitreous ganciclovir in the treatment of cytomegalovirus retinitis. Ophthalmology 105:1404–1410

Janoria KG, Boddu SH, Wang Z, Paturi DK, Samanta S, Pal D, Mitra AK (2009) Vitreal pharmacokinetics of biotinylated ganciclovir: role of sodium-dependent multivitamin transporter expressed on retina. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 25:39–49. doi:10.1089/jop.2008.0040

Hu H, Jabs DA, Forman MS, Martin BK, Dunn JP, Weinberg DV, Davis JL (2002) Comparison of cytomegalovirus (CMV) UL97 gene sequences in the blood and vitreous of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and CMV retinitis. J Infect Dis 185:861–867

Chee SP, Jap A (2008) Presumed Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis and Posner-Schlossman syndrome: comparison of cytomegalovirus-positive and negative eyes. Am J Ophthalmol 146:883–889. doi:S0002-9394(08)00698-3 [pii] 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.09.001 e881

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

None of the authors has any financial interest in this study.

The authors have full control of all primary data and agree to allow Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology to review the data if requested.

Drs. Hwang and Lin contributed equally as co-first authors to this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hwang, YS., Lin, KK., Lee, JS. et al. Intravitreal loading injection of ganciclovir with or without adjunctive oral valganciclovir for cytomegalovirus anterior uveitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 248, 263–269 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-009-1195-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-009-1195-2