Abstract

Introduction

Adult malignant optic nerve gliomas are rare and rapidly fatal visual pathway tumours. They represent a clinical entity different from the more common childhood benign optic nerve gliomas, which are frequently associated with neurofibromatosis I.

Case report

A 61-year-old woman presented with rapidly progressing right vision loss, lower altitudinal visual field defect and papilloedema. MRI showed intraorbital and intracranial swelling of the right optic nerve. Resection of the intracranial part of the right optic nerve up to the chiasm revealed anaplastic astrocytoma grade III. Within 1 year, the patient died of leptomeningeal metastasis despite radiotherapy. Clinical and MRI evaluation of the left eye and optic nerve were normal at all times.

Discussion

Unilateral adult malignant glioma of the optic nerve is exceptional. The final diagnosis was only confirmed by optic nerve biopsy. In the literature, only one patient has been reported with a unilateral tumour manifestation; he was lost to follow-up 3 months later. All other cases were bilateral. To date, 44 case reports of adult malignant optic nerve glioma have been published, either malignant astrocytoma or glioblastoma. These tumours can mimic optic neuritis in their initial presentation. The diagnosis is seldom made before craniotomy. On MRI images, malignant glioma cannot be distinguished from optic nerve enlargement due to other causes. Although radiotherapy appears to prolong life expectancy, all presently available treatment options (radiation, surgery, radio-chemotherapy) are of limited value. Most patients go blind and die within 1 or 2 years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Malignant optic nerve glioma in adults is a rare cause of vision loss. It is a rapidly fatal visual pathway tumour that can mimic optic neuritis in its initial presentation. Hoyt defined the condition and reviewed the first ten cases of malignant optic glioma of adulthood in 1973 [12]. Adult malignant optic gliomas represent a clinical entity different from the more common childhood benign optic gliomas, which are frequently associated with neurofibromatosis I [1, 5, 8, 19].

The present case is the first report of purely unilateral affection until the lethal outcome. Usually malignant optic nerve gliomas progress rapidly over the chiasm to the other side and lead to bilateral vision loss or blindness [5].

Case report

A 61-year-old woman was referred because of vision loss in her right eye and lower visual field defect, which she had noticed 3 weeks before. Best corrected visual acuity was 0.3 OD and 1.0 OS. Slit-lamp examination was normal, and the fundus examination revealed a slight papilloedema OD without haemorrhage. Static perimetry showed a visual field defect OD (Fig. 1a) and was unremarkable OS (Fig. 1b). The patient had a history of treated arterial hypertension and of deep vein thrombosis. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was normal. Non-arteriitic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION) was suspected, and the patient was put on clopidogrel.

Two days later, she presented again with strong headaches and further vision loss to 1/35 OD. The visual field defect OD had progressed (Fig. 1c), and visual field OS was still normal. The papilloedema OD was more pronounced with haemorrhages and venous stasis. Doppler examination of the carotids, echocardiography and clinical neurological examination showed no abnormalities. An MRI scan revealed a thickening of the right optic nerve from the globe to the chiasm with a diameter of 6 mm compared to 3.5 mm on the normal left side (Fig. 2a, b). The thickened optic nerve and nerve sheath as well as the surrounding orbital fat showed a massive, homogeneous contrast enhancement (Fig. 2c–e). The diagnosis seemed now consistent with an inflammatory process, and the patient was put on i.v. antibiotics and steroids, with no effect.

MRI images 8 days after initial presentation. a T1-weighted transversal image demonstrating a thickening of the right optic nerve, b T2-weighted transversal image presenting the thickened right optic nerve with an isointense signal compared to the left optic nerve, c–e T1-weighted contrast enhanced transversal images with spectral fat saturation, c showing the optic chiasm, d revealing an enhancement of the right retrobulbar fat and the right optic nerve, e at the same level as a visualizes the homogenous enhancement of the intraorbital part of the right optic nerve

Two months later, the patient presented to our department with headaches and partial oculomotor palsy of her right eye, which was now totally blind. She also had persisting papilloedema with stasis and cotton wool spots OD (Fig. 3). Examination of the left eye was normal. A control MRI scan (Fig. 4a–c) showed a slightly increased enlargement of the right optic nerve. The enhancement of contrast media of the right optic nerve demonstrated a progression towards the chiasm. There were no signs of intracranial metastasis. The diagnosis appeared no longer consistent with AION or optic neuritis, and a malignant tumour was suspected. A biopsy of the intracranial part of the right optic nerve was planned to get a definitive diagnosis. At surgery, the right optic nerve was thickened and elongated with a grayish hyaline appearance. Rapid section histology was suspicious of an astrocytoma; therefore, the right optic nerve was resected from the posterior part of the optic channel up to the chiasm. The chiasm was clinically free of tumour, which was confirmed by serial rapid section histology. The optic canal was closed intracranially using a duraplasty. Histology showed astrocytic proliferation with high cellular tissue and many atypias without areas of necrosis; the diagnosis was anaplastic astrocytoma grade III (confirmed by the German Reference Centre) (Fig. 5).

MRI images 2 months after initial presentation. a–c T1-weighted contrast enhanced transversal images with spectral fat saturation (corresponding to Fig. 2c–e) showing the optic chiasm and the course of the optic nerve. An increasing enhancement of the right optic nerve is depicted. The contrast enhancement of the intraconal fat tissue is unchanged

MRI examination performed 1.5 months after surgery showed unspecific, post-therapeutic changes, but no remains or relapse of tumour. Three-dimensional radiation was subsequently performed with three-field technique. Follow-up examinations of the left eye including visual field exams were at all times completely normal. The patient was otherwise well.

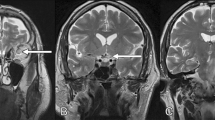

Ten months after initial presentation, the patient was readmitted to hospital because of drowsiness, disorientation and loss of memory. MRI revealed a leptomeningeal dissemination of the tumour with multiple metastases (Fig. 6a). There was a significant decrease of the retroorbital contrast enhancement compared to the previous examinations (Fig. 6b). The optic chiasm and the left optic nerve showed no enhancement (Fig. 6c), thus there was no suspicion of local tumour recurrence in the resected area.

MRI images 10 months after initial presentation (7.5 months after surgery, 3 months after termination of radiotherapy). a T1-weighted contrast enhanced coronal image with spectral fat saturation. A right frontal, left temporal and a subependymal enhancement representing disseminated metastases are visualized. b, c T1-weighted contrast enhanced transversal images with spectral fat saturation (corresponding to Fig. 2c–e and Fig. 4a–c) visualizing the postsurgical situation. The intracranial part of the right optic nerve is resected. The residual optic chiasm shows no pathological enhancement. The enhancement of the right orbital fat is clearly decreased compared to Fig. 2 and Fig. 4

Combined radio-chemotherapy was considered, but the patient’s state deteriorated so quickly that only palliative therapy appeared possible. The patient was delirious and died 12 months after initial presentation in a nursing home. No autopsy was performed.

Discussion

Adult malignant optic gliomas are extremely rare tumours [1, 5, 8, 19]. Until now, 44 cases have been described, not including the present case [1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20, 22, 23, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29]. They are summarised in Table 1.

Of these patients, 51% were male and 49% female; the mean age at diagnosis was 54 years (median 59 years, range 22 to 79 years). At onset, unilateral decreased vision was reported in 70%, bilateral in 30% of the patients. At presentation, 41% of the patients had papilloedema, 30% haemorrhages, 43% visual field defects, 14% optic disc atrophy, 7% ophthalmoplegia and 14% proptosis; 20% of the patients had ocular pain and 39% other neurological deficits, e.g., hemiparesis.

The interval from initial symptoms to total blindness was between 2 weeks and 12 months in the 21 patients with detailed information (mean 3.3 months ± 2.8 months, median 3 months); in eight cases the clinical course, etc., was only described as rapid. In one patient (30 [14]), only bilateral visual field defects and reduced vision were noticed until she was lost to follow-up after surgery.

The anatomic point of origin of this tumour has been a source of controversy in the literature [5, 11]. However, the rapid progression of the disease is the same both for the tumour with chiasmal origin and for that with optic nerve origin [16, 25]. Extension of the tumour to the optic chiasm typically causes contralateral vision loss, temporal hemianopia and bilateral blindness [7]. Therefore, our case is exceptional as the tumour did not locally progress to the chiasm after resection of the tumour of the right optic nerve. Only one other patient out of the 44 cases published has been described with purely unilateral affection and unilateral blindness [7]. However, that patient was not available to follow-up 3 months after the initial diagnosis, so possibly the tumour could have spread to the other side before the death of the patient.

The sites of occurrence of malignant optic glioma except for the chiasma and the optic nerve(s) were found to be the hypothalamus in 50% of patients, the temporal lobe in 22.5% and the basal ganglia in 15%. Other more infrequent sites were the midbrain, parietal cortex, cerebellum and the cervical, thoracic and lumbar subarachnoidal spaces.

Only one case of adult malignant optic nerve glioma developed 8 years after radiotherapy for a recurrent prolactinoma [13]. In all other cases, no radiotherapy or other potentially tumour-promoting events were noted. One report documents the occurrence of a malignant astrocytoma of the optic nerve in an 11-year-old boy who 9 years before had a cerebellar medulloblastoma treated with surgery and radiation. This tumour followed the same aggressive clinical course as that seen in adults [24].

Astrocytomas in general are histologically classified according to the WHO system into four grades. Malignant optic glioma of adulthood is classified histologically as either an anaplastic astrocytoma (WHO grade III, 68% of patients) or a glioblastoma multiforme (WHO grade IV, 29%) [2, 21]. In one case (29 [25]), it was stated to be astrocytoma grade II. The clinical course, however, was more like that of a glioblastoma. As a result, malignant optic glioma represent an unusual presentation of a common tumour of the central nervous system [16].

Mean survival times were 8.3 months (SD 5.6) for the 21 anaplastic astrocytomas and 8.1 months (SD 5.4) for the 9 glioblastomas with full data, respectively. The survival curves of these tumours calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method with statistical evaluation by the log-rank test show that there is no statistically significant difference between the survival of the two neoplasms (P>0.15). Overall mean survival time was 8.6 months (SD 6.1 months, median 8 months, range 1–24 months).

In spite of the introduction of modern imaging techniques, difficulty still remains in making an early diagnosis. An initial diagnosis of optic neuritis is frequently made because of the fairly acute vision loss, disk swelling, retrobulbar pain and the brief visual improvement after intravenous steroids. The differential diagnosis also includes anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Physical signs that raise suspicion for an intraorbital mass are usually absent in the initial stage of the disease [7]. One author stated these lesions to be hypo- to isointense relative to the normal optic nerve on T1-weighted images (as in this patient) and hyperintense on T2-weighted images (not the case in our patient) [7]. He thought that this could be used to distinguish these tumours from other diseases. But most authors agree that on MRI images, enlargement of the optic nerve because of malignant glioma cannot be distinguished from enlargement because of other causes [1, 16]. So in fact the diagnosis of malignant optic glioma is hardly ever made before an exploratory craniotomy, as in our patient, or even autopsy, because it is such a rare tumour [27].

But even if diagnosis of malignant optic glioma could be made early, the question arises concerning how this tumour should be treated. Hoyt stated in 1973 that no known treatment has any effect [12]. Since then, medicine has made a lot of progress, but still all presently available treatment options (surgery, radiation, radio-chemotherapy) are not satisfactory. Of the eight non-treated patients with full data, mean survival was 5.9 months (SD 2.7 months, median 5 months, range 3–9 months); the patients treated with radiotherapy survived a mean of 9.7 months (SD 5.7 months, median 8.5 months, range 3–24 months). This tendency towards longer survival times for the treated patients did not reach statistical significance when calculating survival curves with the Kaplan-Meier method and evaluating them by the log-rank test (P=0.06). Comparison of radiotherapy with (five patients) and without (eight patients with full data) additional chemotherapy found mean survival times of 12.2 and 8.8 months, respectively (SD 8.4 and 4.3 months, median 8 and 9 months, range 5–24 months and 3–20 months, respectively). This was not statistically significant (P>0.15). Additional chemotherapy therefore fails to demonstrate a statistical improvement, but there are not enough cases in the literature to reach a definite decision. Survival rates are not clearly different for surgery and biopsy (P>0.15), and in most cases the tumour spreads quickly to the other side.

Statistical analysis on survival times of patients on the basis of retrospective data is certainly difficult as therapeutic details are not standardised for the different patients. But on the other hand, prospective studies of this disease do not seem possible because of the infrequency of adult malignant gliomas. Radiotherapy may have an advantage in prolonging survival, even though it is not yet statistically significant. This is in accordance with Dario et al., who even found statistical evidence in their subset of patients [5]. It is possible that an attempt at total tumour resection may be at least beneficial for preserving vision of the other eye if only one eye is primarily affected, as in our patient. In patients with bilateral involvement, biopsy should be preferred.

The present case of a 61-year-old woman with unilateral adult malignant glioma of the optic nerve is exceptional. Clinical and MRI evaluation of the fellow eye and optic nerve was normal at all times. This is the first report of documented unilateral malignant optic nerve glioma until the lethal outcome after 12 months. The case is otherwise comparable to the other cases concerning histology, initial clinical presentation and survival time following radiotherapy. Final diagnosis was only possible after biopsy.

Malignant optic nerve glioma certainly is a rare cause of vision loss in the adult population. Most patients go blind and die within 1 year because of tumour spread. Neoplastic disease should be considered if other features do not seem to fit in the diagnosis of optic neuritis or anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (headaches, enlargement of the optic nerve on MRI) or if the clinical course differs (oculomotor palsy, total vision loss) from what is expected.

References

Albers GW, Hoyt WF, Forno LS, Shratter LA (1988) Treatment response in malignant optic glioma of adulthood. Neurology 38:1071–1074

Apple DJ, Rabb MF (1991) Ocular pathology: Clinical applications and self-assessment. Mosby, New York

Barbaro NM, Rosenblum ML, Maitland CG, Hoyt WF, Davis RL (1982) Malignant optic glioma presenting radiologically as a “cystic” suprasellar mass: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 11:787–789

Condon JR, Rose FC (1967) Optic nerve glioma. Br J Ophthalmol 51:703–706

Dario A, Iadini A, Cerati M, Marra A (1999) Malignant optic glioma of adulthood. Case report and review of the literature. Acta Neurol Scand 100:350–353

Evens PA, Brihaye M, Buisseret T, Storme G, Solheid C, Brihaye J (1987) Gliome malin du chiasma chez l’adulte. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol 224:59–60

Friedman DP, Hollander MD (1998) Neuroradiology case of the day. Malignant optic glioma of adulthood. Radiographics 18:1046–1048

Gayre GS, Scott IU, Feuer W, Saunders TG, Siatkowski RM (2001) Long-term visual outcome in patients with anterior visual pathway gliomas. J Neuroophthalmol 21:1–7

Gibberd FB, Miller TN, Morgan AD (1973) Glioblastoma of the optic chiasm. Br J Ophthalmol 57:788–791

Hamilton AM, Garner A, Tripathi RC, Sanders MD (1973) Malignant optic nerve glioma. Report of a case with electron microscope study. Br J Ophthalmol 57:253–264

Harper CG, Stewart-Wynne EG (1978) Malignant optic gliomas in adults. Arch Neurol 35:731–735

Hoyt WF, Meshel LG, Lessell S, Schatz NJ, Suckling RD (1973) Malignant optic glioma of adulthood. Brain 96:121–132

Hufnagel TJ, Kim JH, Lesser R, et al (1988) Malignant glioma of the optic chiasm 8 years after radiotherapy for prolactinoma. Arch Ophthalmol 106:1701–1705

Jamshidi S, Korengold M, Kobrine AI (1984) Computed tomography of an optic chiasm glioma in an elderly patient. Surg Neurol 21:83–87

Manor RS, Israeli J, Sandbank U (1976) Malignant optic glioma in a 70-year-old patient. Arch Ophthalmol 94:1142–1144

Millar WS, Tartaglino LM, Sergott RC, Friedman DP, Flanders AE (1995) MR of malignant optic glioma of adulthood. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 16:1673–1676

Murphy M, Timms C, McKelvie P, Dowling A, Trost N (2003) Malignant optic nerve glioma: metastases to the spinal neuraxis. Case illustration. J Neurosurg 98:110

Pallini R, Lauretti L, La Marca F (1996) Glioblastoma of the optic chiasm. J Neurosurg 84:898–899

Parsa CF, Hoyt CS, Lesser RL, et al (2001) Spontaneous regression of optic gliomas: 13 cases documented by serial neuroimaging. Arch Ophthalmol 119:516–529

Pick A (1901) On the study of true tumours of the optic nerve. Brain 24:502–508

Rao NA, Spencer WH (1991) Optic nerve. In: Spencer WH (ed.) Ophthalmic pathology: An atlas and textbook. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 513–622

Rudd A, Rees JE, Kennedy P, Weller RO, Blackwood W (1985) Malignant optic nerve gliomas in adults. J Clin Neuroophthalmol 5:238–243

Saebo J (1949) Primary tumour of the optic nerve. Br J Ophthalmol 33:701–708

Safneck JR, Napier LB, Halliday WC (1992) Malignant astrocytoma of the optic nerve in a child. Can J Neurol Sci 19:498–503

Shapiro SK, Shapiro I, Wirtschafter JD, Mastri AR (1982) Malignant optic glioma in an adult: initial CT abnormality limited to the posterior orbit, leptomeningeal seeding of the tumor. Minn Med 65:155–159

Spoor TC, Kennerdell JS, Martinez AJ, Zorub D (1980) Malignant gliomas of the optic nerve pathways. Am J Ophthalmol 89:284–292

Taphoorn MJ, Vries-Knoppert WA, Ponssen H, Wolbers JG (1989) Malignant optic glioma in adults. Case report. J Neurosurg 70:277–279

Valdueza JM, Cristante L, Freitag J, Hagel C, Herrmann HD (1995) Malignant chiasmal glioma: a rare cause of rapid visual loss. Neurosurg Rev 18:273–275

Woiciechowsky C, Vogel S, Meyer R, Lehmann R. (1995) Magnetic resonance imaging of a glioblastoma of the optic chiasm. Case report. J Neurosurg 83:923–925

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank C. Sing for the English revision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper was presented in part at the 101st Meeting of the German Ophthalmological Society (DOG).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wabbels, B., Demmler, A., Seitz, J. et al. Unilateral adult malignant optic nerve glioma. Graefe's Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 242, 741–748 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-004-0905-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-004-0905-z