Abstract

Background

Patient-centered assessments have attracted increasing attention in the last decade in clinics and research. The purpose of this study was to examine the association between patients’ satisfaction with symptoms and several disease-specific and generic outcome measures in 100 patients with generalized myasthenia gravis (gMG).

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, patients with gMG followed at the Copenhagen Neuromuscular Center from October 2019 to June 2020 participated in one test. The patients completed commonly used MG-specific outcome measures and generic questionnaires for depression (Major Depression Inventory), comorbidities (Charlson Comorbidity Index), fatigue (Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory), overall health state (EQ-5D-3L), and satisfaction with MG treatment. The analyses were anchored in the Patient Acceptable Symptom State (PASS).

Results

N = 190 patients were screened for the study, and 100 patients were included. One-third of the patients reported dissatisfaction (negative PASS status) with the current symptom state. Increasing MG symptoms, fatigue, depression, low MG-related quality of life, and shorter disease duration were associated with negative PASS status. Age, sex, BMI, MG treatment, and comorbidity did not influence PASS status.

Conclusions

This study shows that dissatisfaction with the current symptom level is high in patients with gMG and that dissatisfaction is associated with disease severity, disease length, depression, fatigue, and lower MG-related quality of life. The results emphasize the importance of a patient-centered approach to MG treatment to optimize patient satisfaction. The PASS question was useful in this study to investigate the causes of symptom dissatisfaction in gMG.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a chronic disease causing fluctuating weakness and fatigue in skeletal muscles, often due to antibodies against acetylcholine receptors in the neuromuscular junction [1]. The estimated number of patients in Denmark is around 1000 [2]. Approximately 380 patients with generalized myasthenia gravis (gMG) are followed at the Copenhagen Neuromuscular Center (CNMC), a specialized neuromuscular outpatient clinic at the Copenhagen University Hospital—Rigshospitalet.

Patient-centered assessments have attracted increasing attention in the last years in clinics and research. However, a challenge is to align patient satisfaction with various outcome measures. The threshold for satisfaction varies among patients, and a new approach to exploring this is the “patient acceptable symptom state” (PASS). PASS can be measured by a simple (yes/no) question, in which the patient answers whether they are satisfied with their current symptom state [3]. PASS has been used in two MG studies [4, 5], demonstrating that around 30% of the patients with MG were dissatisfied. However, previous studies were (1) retrospective, (2) did not compare PASS results with commonly used and clinician-reported MG measurements in the same group of patients, and (3) used limited generic outcome measures. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine factors related to PASS status, both MG-related factors, but also generic factors which might influence PASS status, such as fatigue, depression, and comorbidity.

Methods

Patients and procedures

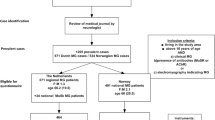

In this cross-sectional study, patients were recruited from CNMC in the period October 2019–June 2020. Patients arriving consecutively for their regular follow-up were invited to participate. We decided a priori to include 100 patients, corresponding to more than a fourth of the total patients with gMG followed in our clinic.

Inclusion criteria for the study were: age ≥ 18 years, a verified diagnosis of gMG, and active medical treatment for MG. Verification of the diagnosis was; a typical clinical history and symptom improvement with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors coupled with either positive acetylcholine receptor, MUSK, or LR4P antibodies and/or significant decrement/increased jitter on electromyography. Exclusion criteria for the study were; competing, severe medical conditions that would interfere with the interpretation of the outcomes, current participation in clinical trials, pregnancy, ocular MG, and if patients were unable to understand Danish or English. For patients meeting the inclusion criteria and accepting to participate, a 1½-hour consultation was arranged. In this consultation, patients completed clinician-reported, MG-specific tests and several MG-specific and generic questionnaires. For patients on pyridostigmine treatment, the test was arranged 1½–2 h after the intake of the drug.

The tests were completed by one of three investigators (LKA, ASJ, or KLR). The three investigators trained together beforehand to conduct the assessments consistently.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Capital Region of Denmark. Informed consent was obtained from all included patients.

Outcome measures

The outcomes were explorative, and the analysis and interpretation of the outcomes were anchored in the patient acceptable symptom state (PASS) question.

The Patient Acceptable Symptom State (PASS) [3] was examined by one dichotomous yes/no question, which reads, “Considering all the ways you are affected by Myasthenia gravis, if you had to stay in your current state for the next months, would you say that you are satisfied with your current disease state”? The questions have previously been used in patients with MG [4, 5].

The Quantitative MG score (QMG) [6] is a 13-item, clinician-derived scale that measures muscle strength and endurance (score range 0–39, higher score indicates more severe MG status).

The MG Composite scale (MGC) [7] is a patient-reported and clinician-derived scale that measures the clinical status of the patients (range 0–56, higher score indicates more severe MG status).

The MG Activities of Daily Living profile (MG-ADL) [8] is an eight-question, clinician-directed but patient-reported questionnaire where higher scores indicate higher disease burden (total score range 0–24). The scale assesses common MG symptoms and dysfunctions. A total score below 3 is regarded as well-treated, and minimal symptom expression corresponds to a score of 0–1 [9].

The MG-specific quality of life (QoL) instrument (MG-QoL15) [10] is a 15-item patient-reported disease-specific QoL questionnaire, consisting of a five-point scale indicating the patient’s agreement with a given statement about MG involvement. Total score ranges from 0 to 60, where higher scores indicate lower MG-related QoL.

The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20) [11] is a patient-reported questionnaire that measures fatigue severity. MFI-20 categorizes fatigue into five domains: general fatigue, physical fatigue, reduced activity, reduced motivation, and mental fatigue. The total score in each domain ranges from 4 to 20, with higher scores indicating higher fatigue levels. MFI-20 has been used in several neurological diseases [12,13,14] and healthy populations but has never been used in patients with MG.

The Major Depression Inventory (MDI) [15, 16] is a patient-reported rating scale, where higher scores indicate more severe depression (range 0–50). The scale is used as a diagnostic tool for depression (score ≥ 20 means clinical depression). MDI has previously been used in patients with MG [17, 18].

The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [19] is an instrument for the long-term mortality prognosis in patients with comorbidities. The point-score ranges from 0 to 37 and is accumulated according to associated diseases and age ranges. A higher score predicts a shorter 10-year survival probability. CCI has previously been used in a study of MG [20].

The EQ-5D-3L [21] is a generic classification system for measuring health-related QoL, compromising the five dimensions; mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and depression/anxiety. The index score is derived from three different questions in each dimension, giving an index ranging from 0 to 1; 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health) [22]. An EQ-VAS scale ranging from 0 to 100 (100 = the best health you can imagine) was also included, indicating the patient’s self-rated overall health status. EQ-5D-3L has previously been used in patients with MG [4].

As we expected that the satisfaction with adverse effects of the MG medical treatment would influence on PASS status, and as no such easy-to-use instrument is developed for patients with MG, we simply asked the patient one question: “How satisfied are you with the current adverse effects of your medical treatment for MG? Satisfaction was scored on a VAS scale ranging from 1 to 10 (1 = not at all satisfied to 10 = very satisfied).

Patient- and disease-related background information was obtained: age, sex, weight, and height (used to calculate body mass index, BMI), occupational status, MG duration, MG treatment, and antibody- and thymectomy status.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were presented by means ± standard deviation (SD) when data were normally distributed and medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) when this was not the case. Normality was determined visually by histograms and boxplots. Categoric variables were presented by numbers (n) and percentages (%).

The difference in distribution was investigated by unpaired t test for continuous data, Mann–Whitney test for non-normal distributed continuous data, and Fisher’s exact test for categorical data. Correlation between tests was estimated by the non-parametric Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients.

To identify factors associated with PASS status, logistic regression models were applied, using PASS as a dichotomous outcome: positive (yes) /negative (no). In the adjusted analyses, the covariates were age, sex, disease length, MG disease severity (QMG), and depression (MDI), which were selected a priori and determined from available evidence or experiences from the clinic. The QMG was included as this was the only entirely objective measurement of disease symptoms, and depression score was included as depressive symptoms were expected to influence symptom satisfaction. More covariates could be relevant, but the numbers were limited to avoid mass significance in the analyses. The regression models were executed as complete-case analysis and checked for (1) overall Goodness-of-fit, (2) linearity of covariates by adding log-transformed covariates into the model, (3) interaction and (4) test of accumulated residuals by plots and p-values. The convergence criterion was satisfied in all analyses.

For analyses, a p ≤ 0.05 (two-tailed testing) was considered significant. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS enterprise guide 7.1.

Data availability statement

The individual de-identified participant data, the study protocol, and statistical analyses plan will be shared by request from any qualified investigator.

Results

To reach the desired number of 100 patients, we consecutively screened 190 patients for eligibility (by checking their medical records) when they arrived in the clinic for their regular follow-up with a neurologist. Of these, 34 did not meet the inclusion criteria (due to ocular MG (n = 8), currently not on medical treatment for MG (n = 11), or severe comorbidity that could influence the interpretation of test results, e.g., severe COPD or hemiparalysis (n = 15)). Of the remaining 156 invited to participate in the study, one patient was pregnant, one patient had language issues, and 54 patients refused for practical issues, such as lack of time or long transportation.

Of the included patients, 57 were women with a mean age at disease onset of 45.6 ± 19.8 years. Men were generally older at disease onset; 56.7 ± 15.3 years (p < 0.001). The median disease duration was 6 (IQR 3–13) years. In total, 66 patients were on pyridostigmine treatment, of whom 20 patients were treated solely with this drug. Twenty-four patients were in prednisolone treatment (mean dose 15.8 mg/daily) combined with other MG drugs. Table 1 shows some characteristics of the sample.

Thirty-three patients answered “no” to the PASS question, while 67 patients were satisfied. Compared to PASS-positive patients, the dissatisfied patients had shorter disease duration (median 3 vs. 8 years, p = 0.001) and were more often unemployed or on disability (p = 0.033). Also, the PASS-negative patients had higher scores on all outcome measures (p < 0.05), except for comorbidity (p = 0.767) compared to satisfied patients. The MG medical treatment differed between PASS groups (p = 0.028), whereas this was not the case for age, sex, BMI, and antibody- and thymectomy status (Table 2). There were no differences in prednisolone dose between the groups (p = 0.120).

PASS-negative status was associated (p < 0.05) with both clinician-measured outcome (QMG), patient-reported outcomes (MG-ADL, MG-QoL15, MFI-20, MDI), and disease duration. Increasing MG severity, MG-related quality of life scores, fatigue, and depression, as well as short disease duration, increased the odds for negative PASS answers. Age, sex, BMI, MG medical treatment (both overall and prednisolone), MGC scores, and comorbidity were not associated with PASS status in the adjusted analyses (Table 3).

The correlation between MG-ADL and QMG was low (r = 0.50, p < 0.0001) to modest (r = 0.79, p < 0.0001), depending on the inclusion/exclusion of outliers. The distribution of patients with the most prominent distinction between patient-reported and clinician-derived outcomes was equally between PASS-negative and -positive respondents (p = 0.596). Also, a prominent distinction was not associated with a PASS-negative answer (p = 0.208).

Twenty patients had an MDI score ≥ 20, indicating depression. The distribution of depressed patients differed between PASS groups (p = 0.007), with 38% (n = 12) of the PASS-negative patients having clinical depression, vs. 12% (n = 8) in the PASS-positive group. A high MDI score increased the odds for PASS-negative status (odds ratio, OR: 1.10, confidence interval, CI: 1.03–1.17, p = 0.003).

The median score of satisfaction with current adverse effects of MG medical treatment was 8 (IQR 5–9). N = 41 patients reported a score below the sample median of 8. Of the PASS-negative patients, 64% (n = 21) had low satisfaction (< 8) with adverse effects, whereas this was only 30% (n = 20) of the PASS-positive patients (p = 0.002).

Discussion

In this study, we used PASS to probe into the underlying cause of dissatisfaction by simultaneously assessing a wide range of MG-specific and -generic outcomes in a cohort of 100 patients with gMG. The results demonstrate that one-third of the included patients were dissatisfied with their current symptom state. Our findings show that dissatisfaction is associated with disease severity, short disease duration, depression, fatigue, and low MG-related quality of life.

High MG-ADL scores were associated with higher odds for dissatisfaction than the clinician-derived QMG, which underscores the relevance of subjective, patient-reported scores in assessing MG symptoms. No previous studies have compared PASS status with these MG measurements in the same group of patients.

The PASS-negative patients had higher self-reported physical- and general fatigue scores than the PASS-positive patients, and fatigue was strongly associated with PASS-negative status. Increasing general fatigue had almost similar odds for PASS-negative status as physical fatigue, emphasizing that in addition to physical fatigue as a core symptom in MG, general fatigue plays a vital role in the well-being and rehabilitation of patients with gMG.

One-fifth of the included patients had an MDI score indicating clinical depression, aligning with previous studies on depression in MG [23,24,25,26]. In non-MG studies that included patients with rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis, the prevalence of depression was found to be even higher (≥ 30%) [27, 28]. High MDI scores were a significant factor for PASS-negative status.

Comorbidity was not associated with PASS-negative status, which likely relates to the low occurrence of non-age-related comorbidities in the cohort. In comorbid patients, the most frequent diseases were diabetes type 2 and hypertension, with a prevalence corresponding to the general Danish population [29, 30]. As in the background population, there was a higher incidence of comorbidities with increasing age.

More PASS-negative patients reported low satisfaction with adverse treatment effects than PASS-positive patients. Prednisolone is known to cause undesirable adverse effects when used long-term and/or at high doses, which could explain the dissatisfaction. An American register study [31] reported that 42% of patients received corticosteroids and 55–58% in a Canadian study [4]. These ratios are significantly higher than the 24% observed in our cohort, and we speculate if dissatisfaction with adverse effects is higher in other parts of the world. However, we found that MG treatment was not associated with PASS-negative status. Also, despite the frequent use of corticosteroids in the Canadian cohort [4], the proportion of PASS-negative patients was similar to our findings. However, the results might be biased by differences in the cohorts, as we exclusively enrolled patients with gMG.

Disease duration in the PASS-negative patients was more than halved compared to PASS-positive patients. A possible explanation might be that newly diagnosed patients still have not reached stabilization on optimal treatment (i.e., without unacceptable side effects) or are psychologically troubled by contracting a new, chronic disease that changes ADL and social functions.

In one retrospective validation cohort [4], PASS answers determined cut-off scores for MG-ADL, MGC, and MG-QoL15. Applying these cut-off scores to our population led to a proportion of 49–70% PASS-negative patients, which is different from the actual 33%. Although our cohort resembled previous cohorts [4] regarding age, sex, disease duration, and the number of PASS-negative patients, the cut-off points for MG measurements are not aligned. This might be explained by cultural differences or, more importantly, due to differences in study design, as our study is cross-sectional, while previous ones were retrospective studies.

We chose a wording of the PASS questions inspired by Mendoza et al. [4]. The Danish version of this PASS question has never been validated in Danish MG patients. However, as PASS is an approach to evaluating patient satisfaction individually, not a questionnaire, the wording differs between studies. Therefore, we believe that a validation of the Danish version is not needed.

The study design allowed us to combine PASS and MG measurements in one sample, which reduced the risk of selection bias. However, a total of 54 patients refused the study invitation for practical reasons. If lack of willingness relied on dissatisfaction with MG symptoms, this could lead to a selection of too many satisfied patients. However, none of the 54 patients expressed dissatisfaction as a reason for refusing, and we do not believe that these patients were more dissatisfied than the included patients. Still, it is not possible to estimate the impact of this potential selection bias.

We believe our findings represent the Danish MG population, as Danish MG patients are treated according to national guidelines and allocated at hospitals based on residence and not by disease severity or socioeconomic status. We used a combination of patient-reported and clinician-derived measurements, both MG-specific and generic, which allowed us to examine the PASS status from a broader perspective. The PASS question could be a valuable tool for assessing patient perspectives in follow-up and clinical trials based on this study. However, further evaluations of to what extent the PASS question applies to other MG populations are needed, primarily when treatment algorithms differ.

Conclusion

One-third of the included patients with gMG reported dissatisfaction with their current symptom state. These patients reported severe MG symptoms, low disease duration and MG-related quality of life, and high levels of fatigue and depression but resembled the remaining patients regarding demographics and disease status. The results suggest that a broader perspective on the disease, than strictly focusing on objective symptoms and treatment, is vital in the clinic to understand the underlying causes of dissatisfaction. For this, the PASS question could be a relevant and easy-to-use tool. A particular focus on newly diagnosed patients is crucial, as these patients seem more often dissatisfied.

References

Gilhus NE (2016) Myasthenia Gravis. N Engl J Med 375(26):2570–2581

Hansen JS, Danielsen DH, Somnier FE, Frøslev T, Jakobsen J, Johnsen SP et al (2016) Mortality in myasthenia gravis: A nationwide population-based follow-up study in Denmark. Muscle Nerve 53(1):73–77

Wijeysundera DN, Johnson SR (2016) How much better is good enough?: Patient-reported outcomes, minimal clinically important differences, and patient acceptable symptom states in perioperative research. Anesthesiology 125(1):7–10

Mendoza M, Tran C, Bril V, Katzberg HD, Barnett C (2020) Patient-acceptable symptom states in myasthenia gravis. Neurology. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000010574

Menon D, Barnett C, Bril V (2020) Comparison of the single simple question and the patient acceptable symptom state in myasthenia gravis. Eur J Neurol 27(11):2286–2291

Tindall RS, Rollins JA, Phillips JT, Greenlee RG, Wells L, Belendiuk G (1987) Preliminary results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of cyclosporine in myasthenia gravis. N Engl J Med 316(12):719–724

Burns TM, Conaway MR, Cutter GR, Sanders DB (2008) Muscle study. Group construction of an efficient evaluative instrument for myasthenia gravis: the MG composite. Muscle Nerve 38(6):1553–1562

Wolfe GI, Herbelin L, Nations SP, Foster B, Bryan WW, Barohn RJ (1999) Myasthenia gravis activities of daily living profile. Neurology 52(7):1487–1489

Vissing J, Jacob S, Fujita KP, O’Brien F, Howard JF (2020) REGAIN study group “Minimal symptom expression” in patients with acetylcholine receptor antibody-positive refractory generalized myasthenia gravis treated with eculizumab. J Neurol 267(7):1991

Burns TM, Conaway MR, Cutter GR, Sanders DB (2008) Muscle study. Group Less is more, or almost as much: a 15-item quality-of-life instrument for myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 38(2):957–963

Smets EM, Garssen B, Bonke B, De Haes JC (1995) The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res 39(3):315–325

Mikula P, Nagyova I, Krokavcova M, Vitkova M, Rosenberger J, Szilasiova J et al (2015) The mediating effect of coping on the association between fatigue and quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis. Psychol Health Med 20(6):653–661

Visser MM, Goodin P, Parsons MW, Lillicrap T, Spratt NJ, Levi CR et al (2019) Modafinil treatment modulates functional connectivity in stroke survivors with severe fatigue. Sci Rep 9(1):9660

Lexell J, Jonasson SB, Brogardh C (2018) Psychometric properties of three fatigue rating scales in individuals with late effects of polio. Ann Rehabil Med 42(5):702–712

Bech P, Rasmussen NA, Olsen LR, Noerholm V, Abildgaard W (2001) The sensitivity and specificity of the major depression inventory, using the present state examination as the index of diagnostic validity. J Affect Disord 66(2–3):159–164

Olsen LR, Jensen DV, Noerholm V, Martiny K, Bech P (2003) The internal and external validity of the major depression inventory in measuring severity of depressive states. Psychol Med 33(2):351–356

Rahbek MA, Mikkelsen EE, Overgaard K, Vinge L, Andersen H, Dalgas U (2017) Exercise in myasthenia gravis: A feasibility study of aerobic and resistance training. Muscle Nerve 56(4):700–709

Paul RH, Cohen RA, Goldstein JM, Gilchrist JM (2000) Fatigue and its impact on patients with myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 23(9):1402–1406

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40(5):373–383

Mouri H, Jo T, Matsui H, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H (2020) Effect of sugammadex on postoperative myasthenic crisis in myasthenia gravis patients: propensity score analysis of a japanese nationwide database. Anesth Analg 130(2):367–373

EQ-5D [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 28]. Available from: https://euroqol.org/

Wittrup-Jensen KU, Lauridsen J, Gudex C, Pedersen KM (2009) Generation of a danish TTO value set for EQ-5D health states. Scand J Public Health 37(5):459–466

Gavrilov YV, Alekseeva TM, Kreis OA, Valko PO, Weber KP, Valko Y (2020) Depression in myasthenia gravis: a heterogeneous and intriguing entity. J Neurol 267(6):1802–1811

Alekseeva TM, Gavrilov YV, Kreis OA, Valko PO, Weber KP, Valko Y (2018) Fatigue in patients with myasthenia gravis. J Neurol 265(10):2312–2321

Hoffmann S, Ramm J, Grittner U, Kohler S, Siedler J, Meisel A (2016) Fatigue in myasthenia gravis: risk factors and impact on quality of life. Brain Behav 6(10):e00538

Kittiwatanapaisan W, Gauthier DK, Williams AM, Oh SJ (2003) Fatigue in myasthenia gravis patients. J Neurosci Nurs J Am Assoc Neurosci Nurs 35(2):87–93

Matcham F, Rayner L, Steer S, Hotopf M (2013) The prevalence of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Oxf Engl 52(12):2136–2148

Boeschoten RE, Braamse AMJ, Beekman ATF, Cuijpers P, van Oppen P, Dekker J et al (2017) Prevalence of depression and anxiety in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci 372:331–341

Carstensen B, Rønn PF, Jørgensen ME (2020) Prevalence, incidence and mortality of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in Denmark 1996–2016. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-001071

Ibsen H, Jørgensen T, Jensen GB, Jacobsen IA (2009) Hypertension–prevalence and treatment. Ugeskr Laeger 171(24):1998–2000

Cutter G, Xin H, Aban I, Burns TM, Allman PH, Farzaneh-Far R et al (2019) Cross-sectional analysis of the myasthenia gravis patient registry: disability and treatment. Muscle Nerve 60(6):707–715

Funding

N/A.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LKA and AJ have full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: Vissing. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: All authors. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: Andersen. Obtained funding: Vissing. Administrative, technical, or material support: Andersen, Jakobsson. Supervision: Vissing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Vissing received an unrestricted grant from Argenx to cover salary and patient transport expenses. The company had no influence on study design or in the writing of the manuscript. Andersen, Jakobsson, and Revsbech report no disclosures.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Capital Region of Denmark.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all included patients.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andersen, L.K., Jakobsson, A.S., Revsbech, K.L. et al. Causes of symptom dissatisfaction in patients with generalized myasthenia gravis. J Neurol 269, 3086–3093 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10902-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-021-10902-1