Abstract

Randomized studies have reported a positive effect of candesartan, an angiotensin II receptor antagonist, in migraine prevention. The aim of our study was to explore patient subjective efficacy of candesartan in a real-world sample of migraine patients and try to identify predictors of candesartan response. We audited the clinical records of 253 patients who attended the King’s College Hospital, London, from February 2015 to December 2017, looking specifically at their response to candesartan. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used to identify predictors of headache benefit. Odds ratios (OR) with confidence intervals (CI) 95% were calculated. Eighty-one patients (chronic migraine, n = 68) were included in the final analysis. Thirty-eight patients reported a positive response to candesartan, while 43 patients did not have a meaningful therapeutic effect. The median dose of candesartan was 8 mg and the median treatment period was 6 months. In a univariate logistic regression model, the presence of daily headache was associated with reduced odds of headache benefit (OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.16–0.96, p = 0.04). In multivariate logistic regression model, younger age (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.87–0.98, p = 0.006) and longer disease duration (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.01–1.12, p = 0.03) were associated with a good response to candesartan, while the presence of daily headache was associated with reduced odds of headache benefit (OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.04–0.71, p = 0.01). Having failed up to nine preventives in patients did not predict a treatment failure with candesartan as well. Candesartan yields clinical benefits in difficult-to-treat migraine patients, irrespective of previous failed preventives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A range of therapies are currently available for migraine prevention, with most, excepting calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) pathway monoclonal antibodies, having ill-defined mechanisms [1, 2]. Predictors of response to a particular treatment have not been identified for any preventive or sub-type of migraine. Candesartan, an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker, is an effective and well-tolerated, commonly used migraine preventive drug [3]. Randomized placebo-controlled trials (RCTs) [4, 5] have shown candesartan 16 mg is effective, and comparable to propranolol, in reducing the number of headache days in migraine patients. One small case series has demonstrated the efficacy of candesartan for treating migraine patients with comorbid hypertension in real life [6]. In this study, we wished to explore patient subjective efficacy of candesartan in migraine prevention in a cohort of migraine patients, which included those who had failed previous preventives. We also sought to identify response predictors to candesartan. The work has been reported in preliminary form at the 4th Congress of the European Academy of Neurology (June 16–19, Lisbon) [7].

Methods

Study design and study population

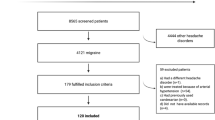

We reviewed the clinical history of migraine patients who attended the Headache Clinic at King’s College Hospital between February 2015 and March 2018 and to whom candesartan had been prescribed as a migraine preventive. Inclusion criteria for patients were initiation of treatment with candesartan under our care, at least an initial consultation note at the start of treatment and a follow-up clinical note, and having an adequate course of candesartan for at least 2 months [8]. Exclusion criteria for patients were having tried candesartan for less than 2 months, a concurrent diagnosis of migraine and other forms of headache, and missing clinical data. Candesartan was started at a dose of 2 mg and, if needed, slowly increased until therapeutic effects develop or adverse events were intolerable.

The primary audit question was whether patients in our referral clinic derived any degree of benefit from taking candesartan. Specifically, during the visit we asked patients whether they have noticed a reduction in the number of headache days, migraine days or in the severity of migraine attacks while having candesartan. A positive response in any of these variables was reported in the patient’s clinical letter as a positive subjective treatment response. All patients met the then standard diagnostic criteria of the International Classification of Headache Disorders [9]. Where possible, the following information was collected from medical records for each patient: age, gender, headache diagnosis, presence of aura, history of medication overuse, presence of cutaneous allodynia, disease duration, headache frequency defined as the number of days per month when some head discomfort was experienced, migraine attack frequency, other headache treatments tried for prevention, presence of comorbid psychiatric diseases and hypertension, doses of candesartan used, duration of treatment, and side effects and patient-reported clinical effect on headache in terms of improvement in migraine attack frequency or severity.

Standard protocol approvals and registrations

The audit was registered with the King’s College Hospital Neurology Department Audit Committee.

Data analysis

Responders’ and non-responders’ demographic and clinical characteristics were compared using the independent t test or Mann–Whitney test for continuous or discrete variables, and the Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were performed to evaluate potential predictors of headache benefit such as patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics. Given the exploratory nature of the study, multivariate stepwise regression with backward selection of covariates was performed. Multicollinearity was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF). Model fits were screened for the presence of outliers and for lack of fit using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. Odds ratios (OR) were calculated with a confidence interval (CI) of 95%. Analysis was performed using SPSS software.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Results

The clinical history of 253 patients was reviewed. A total of 81 patients (62 females), with a mean age of 45 years (± 16, SD), who had candesartan for at least 2 months were included in the final analysis. One hundred and seventy-two patients were excluded due to missing data or for the contemporary presence of other forms of headache, such as cluster headache, or post-traumatic headache. The main demographic and clinical characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1. Thirteen patients had episodic migraine, while 68 patients had chronic migraine. Forty-six patients reported having daily headache. Seventy-four patients had tried other preventives including beta-blockers, sodium valproate, topiramate, amitriptyline, flunarizine, gabapentin, pizotifen, methysergide, onabotulinum toxin A and single pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation. The median dose of candesartan was 8 mg (interquartile range: 4–16) and the median treatment period was 6 months (interquartile range: 3–8). The maximum dose of candesartan was 24 mg and the longest treatment period was two-and-a-half years. Twenty-five patients (31%) experienced side effects, with dizziness, nausea, lightheadness, fatigue and low blood pressure being the most common.

Headache outcome

Thirty-eight patients (47%) reported a positive response to candesartan, while 43 patients (53%) did not have a significant therapeutic effect. There were no differences in demographic and clinical variables between responders and non-responders, except from a higher incidence of daily headache in non-responders (Table 1).

Modeling predictors of outcome

In univariate logistic regression modeling, the presence of daily headache was associated with reduced odds of headache benefit (OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.16–0.96, p = 0.04). In multivariate logistic regression model, younger age (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.87–0.98, p = 0.006) and longer disease duration (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.01–1.12, p = 0.03) were associated with a good response to candesartan, while the presence of daily headache was associated with reduced odds of headache benefit (OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.04–0.71, p = 0.01). Headache frequency was excluded from the model due to VIF values higher than 10. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test for the final model was consistent with an acceptable fit to the data (p = 0.82).

Discussion

Here, we have provided clinical experience confirming the benefits and tolerability of candesartan in migraine prevention in a cohort of real-world migraine patients. Forty-seven percent of the total patient cohort reported a positive effect of candesartan. Despite the different measures of efficacy, the outcome is comparable to the RCTs [4, 5], and we have observed a positive response using a lower dosage of candesartan. Non-response in a substantial cohort of patients is consistent with outcomes from all current preventives, likely based on dose limitations with side effects and biological variability between patients. Candesartan is not perfect; however, it is easy to use, generally well tolerated, safe and of low cost, such that it is a useful tool in the neurologist’s hands for the preventive treatment of migraine.

An important finding here is that challenging migraine patients, such as patients with chronic migraine, long disease duration and who have failed to respond to other preventives, can benefit from candesartan as migraine prevention. Contrary to our findings, some studies have shown an association between short disease duration and better treatment response to onabotulinumtoxinA [10, 11]. Different mechanisms of action of the two treatments might explain this incongruity.

Given the tertiary clinic base for the sample, many patients had daily headache. Migraine patients with daily headache are one of the most substantial management challenges in headache clinics. The poor treatment response we have found in association with the presence of daily headache supports the complexity of these subgroup of patients. Interestingly, having failed up to nine preventives in patients did not predict a treatment failure with candesartan as well. Prospective studies targeting patients who have failed previous preventives are now emerging for up to four failures [12,13,14], and suggest, as we do here, that previous preventive failure is not invariably a predictor of the response to another preventive.

Our cohort covers a wide age range of adult migraine patients, providing evidence of efficacy and safety also in patients who are over 65 years and who were not studied in previous RCTs [4, 5], even if younger patients were found to be relatively more likely to benefit from candesartan. Likewise, an association between younger age and better response to onabotulinumtoxinA [10] and detoxification treatment [15] has been demonstrated. Further studies investigating predictors of treatment response in migraine patients are warranted. New evidence might help us to better understand the interaction between age and disease duration in predicting treatment response in migraine.

The tolerability and side effects of candesartan were comparable with the existing literature [4, 5], with dizziness and tiredness being the most common side effects reported. It is also worth noting that prolonged treatment with candesartan for up to 2 years was well tolerated.

The main limit of the study is its retrospective design. The use of clinic letters to ascertain patient subjective candesartan response is clearly not as effective as using an established measure of headache treatment efficacy (e.g., 50% reduction of monthly migraine days). Future prospective studies should investigate the treatment response to candesartan using patients’ headache diaries. A longer follow-up of patients would provide information regarding candesartan response and tolerability over a longer period.

In this new era of migraine treatment where different options are available, the good efficacy, tolerability and the low cost make candesartan an attractive option for migraine prevention. Optimized preventive treatments tailored to the individual patient are essential to improve migraine patients’ management. The choice of preventive treatment in migraine is still made by trial, and predictors that can help to identify which patient would respond to a specific prevention are still lacking. Our results encourage neurologists to be cautiously optimistic when dealing with patients who have failed previous preventives and offer a specific, simple option that has not been widely deployed.

References

Migraine CA (2017) N Engl J Med 377(17):1698–1699

Dodick DW (2019) CGRP ligand and receptor monoclonal antibodies for migraine prevention: evidence review and clinical implications. Cephalalgia 39(3):445–458

American Headache Society (2019) The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache 59(1):1–18

Tronvik E, Stovner LJ, Helde G, Sand T, Bovim G (2003) Prophylactic treatment of migraine with an angiotensin II receptor blocker: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 289(1):65–69

Stovner LJ, Linde M, Gravdahl GB, Tronvik E, Aamodt AH, Sand T et al (2014) A comparative study of candesartan versus propranolol for migraine prophylaxis: a randomised, triple-blind, placebo-controlled, double cross-over study. Cephalalgia 34(7):523–532

Owada K (2004) Efficacy of candesartan in the treatment of migraine in hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res 27(6):441–446

Messina R, Lastarria C, Filippi M, Goadsby PJ (2018) Predicting treatment response to candesartan in migraine patients. Eur J Neurol 25(Suppl 2):112

Silberstein SD (2015) Preventive migraine treatment. Continuum 21(4):973–989

Headache Classification Committee of the IHS (2013) The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 33(9):629–808

Eross EJ, Gladstone JP, Lewis S, Rogers R, Dodick DW (2005) Duration of migraine is a predictor for response to botulinum toxin type A. Headache 45(4):308–314

Dominguez C, Pozo-Rosich P, Torres-Ferrus M, Hernandez-Beltran N, Jurado-Cobo C, Gonzalez-Oria C et al (2018) OnabotulinumtoxinA in chronic migraine: predictors of response. A prospective multicentre descriptive study. Eur J Neurol 25(2):411–416

Reuter U, Goadsby PJ, Lanteri-Minet M, Wen S, Hours-Zesiger P, Ferrari MD et al (2018) Efficacy and tolerability of erenumab in patients with episodic migraine in whom two-to-four previous preventive treatments were unsuccessful: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b study. Lancet 392(10161):2280–2287

Ferrari MD, Diener HC, Ning X, Galic M, Cohen JM, Yang R et al (2019) Fremanezumab versus placebo for migraine prevention in patients with documented failure to up to four migraine preventive medication classes (FOCUS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet 394(10203):1030–1040

Mulleners WM, Kim BK, Láinez MJ, Lanteri-Minet M, Aurora SK, Nichols RM et al (2019) A randomized, placebo-controlled study of galcanezumab in patients with treatment-resistant migraine: double-blind results from the CONQUER study. Cephalalgia 39(1S):366

Tribl GG, Schnider P, Wober C, Aull S, Auterith A, Zeiler K et al (2001) Are there predictive factors for long-term outcome after withdrawal in drug-induced chronic daily headache? Cephalalgia 21(6):691–696

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RM: patient enrollment, analysis and interpretation of the data, statistical analysis and drafting/revising the manuscript. CPLP: patient enrollment. MF: interpretation of the data and drafting/revising the manuscript. PJG: patient enrollment, study concept, interpretation of the data and drafting/revising the manuscript. He also acted as study supervisor.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

R. Messina declares, unrelated to this work, compensation for speaking activities from Novartis, Eli Lilly and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries. C. P. Lastarria Pèrez have no conflict of interest related to the publication of this manuscript. M. Filippi declares, unrelated to this work, compensation for consulting services and/or speaking activities from Bayer, Biogen Idec, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme, Takeda, and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries; and receives research support from Biogen Idec, Merck-Serono, Novartis, Roche, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, Italian Ministry of Health, Fondazione Italiana Sclerosi Multipla, and ARiSLA (Fondazione Italiana di Ricerca per la SLA). Prof. Filippi is Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Neurology. P. J. Goadsby reports unrelated to the work, over the last 36 months, grants and personal fees from Amgen and Eli-Lilly and Company, grant from Celgene, and personal fees from Aeon Biopharma, Alder Biopharmaceuticals, Allergan, Autonomic Technologies Inc., Biohaven Pharmaceuticals Inc., Clexio, Electrocore LLC, Epalex, eNeura, Impel Neuropharma, MundiPharma, Novartis, Santara Therapeutics, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Trigemina Inc., WL Gore, and personal fees from MedicoLegal work, Massachusetts Medical Society, Up-to-Date, Oxford University Press, and Wolters Kluwer; and a patent magnetic stimulation for headache assigned to eNeura without fee.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The audit was registered with the King’s College Hospital Neurology Department Audit Committee.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Messina, R., Lastarria Perez, C.P., Filippi, M. et al. Candesartan in migraine prevention: results from a retrospective real-world study. J Neurol 267, 3243–3247 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-09989-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-09989-9