Abstract

Ménière’s disease (MD) is characterized by episodic vertigo, fluctuating hearing loss and tinnitus. Vestibular migraine (VM) is a relatively new disorder that is characterized by episodic vertigo or dizziness, coexisting migraine and absence of hearing loss. It is occasionally difficult to distinguish between VM and vestibular MD with headache. Because endolymphatic hydrops (EH) is a characteristic sign of MD, we attempted to evaluate endolymphatic space size in both diseases. Endolymphatic space size in the vestibule and the cochlea was evaluated in seven patients with VM and in seven age- and sex-matched patients with vestibular MD. For visualization of the endolymphatic space, 3T magnetic resonance imaging was taken 4 h after intravenous injection of gadolinium contrast agents using three-dimensional fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and HYbriD of reversed image of positive endolymph signal and native image of positive perilymph signal techniques. In the vestibule of VM patients, EH was not observed, with the exception of two patients with unilateral or bilateral EH. In contrast, in the vestibule of patients with vestibular MD, all patients had significant EH, bilaterally or unilaterally. These results indicate that endolymphatic space size is significantly different between patients with VM and vestibular MD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Vestibular migraine (VM) and Ménière’s disease (MD) are frequent causes of episodic vertigo. Comorbidity is common between VM and MD, and their symptoms overlap [1–9]. More specific diagnostic criteria are needed to differentiate these diseases and to address their coexistence [10]. Endolymphatic hydrops (EH) have been considered as a characteristic sign of MD. According to the criteria of MD defined by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAOHNS) in 1995 (Table 1), certain patients with definite MD diagnosed during their lives require histological confirmation of EH after death [11]. VM is a relatively new disorder that is characterized by episodic vertigo or dizziness, coexisting migraine and shortage of hearing loss [1]. Recently, diagnostic criteria for VM have been proposed in which vestibular complaints are associated with headache by three out of the five criteria proposed by the International Headache Society for the diagnosis of migraine with or without aura. These criteria are quite loose and have been opposed for leading to the inclusion of too many migrainous patients with vertigo [12].

Fluctuating hearing loss, episodic vertigo and tinnitus are characteristic symptoms of MD. However, it has been assumed that there are many patients who have EH with only hearing loss, only vertigo or only tinnitus. In 1972, the American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology (AAOO) defined vestibular MD as the presence of episodic vertigo without hearing loss, and cochlear MD as the presence of fluctuating hearing loss without vertigo (Table 2) [13]. However, in 1995, the AAOHNS excluded the term vestibular MD or cochlear MD considering the possibility of the absence of EH in these atypical types of MD. According to the definition of the AAOHNS, vestibular variants without cochlear symptoms and cochlear variants without disequilibrium are classified as possible MD (Table 1). The diagnostic criteria used to differentiate between MD and VM are unfortunately not helpful because of the loose connection of the complaint with headache and/or aura [14]. Radtke et al. [15] followed a group of people with possible VM for 9 years and showed that the accuracy of the predictive values based on possible VM was about 50 %. Clinicians are left with the task of diagnosing and treating these patients with overlapping symptoms. More specific diagnostic criteria are needed to differentiate these diseases and address their coexistence.

The state of VM and that of vestibular MD are very similar, and it is difficult to distinguish them. Recently, visualization of EH was performed using 3T magnetic resonance imaging (3T MRI) after the administration of gadolinium contrast agents [16–20]. In the present study, we attempted to compare the size of the endolymphatic space in patients with VM with that in patients with vestibular MD.

Methods

Patients

The subjects included in this investigation were seven patients diagnosed with definite VM (mean age, 46 ± 17 years) according to the criteria described by Radtke et al. [15] (Table 3), and seven age- and sex-matched patients with vestibular MD (mean age, 47 ± 16 years). All patients received endolymphatic space size evaluation and pure tone audiometry and exhibited a normal or age-matched hearing level. Patients with vestibular MD were selected to match each VM patient under the condition of the same sex and nearest age. In one patient for whom a matching patient of the same sex with age ± 5 years was not available, a patient who had a 3-year difference and the opposite sex was selected.

Evaluation of endolymphatic space size

For the evaluation of endolymphatic space size, 3T MRI was used. The details of the method were described previously [16–20]. Briefly, 4 h after the intravenous injection of gadolinium contrast agents, 3T MRI was taken using heavily T2-weighted three-dimensional fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (3D-FLAIR) and HYbriD of reversed image of positive endolymph signal and native image of positive perilymph signal (HYDROPS) techniques. We used intravenous injection of a standard dose (0.2 mL/kg body weight, i.e., 0.1 mmol/kg body weight) of gadodiamide hydrate (Omniscan; GE Healthcare). All scans were performed using a 3T MRI scanner (Magnetom Verio; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a receive-only, 32-channel, phased-array coil [21]. A radiologist who did not know the clinical symptoms classified the degree of EH in the vestibule and cochlea into three grades according to the criteria described previously: none, mild and significant (Table 4) [22].

Statistics

The data were analysed with SPSS 20.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Differences between the groups regarding the grade of EH were assessed using a Fisher’s exact test. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

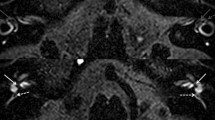

The endolymphatic space size could be evaluated in all 28 ears of the 14 patients included in the study. Figure 1 shows examples of enlarged and normal endolymphatic spaces in the vestibule and cochlea. The results of the evaluation of the endolymphatic space size in patients with vestibular MD and VM are summarized in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. In all patients with vestibular MD, EH in the vestibule was observed bilaterally. In the cochlea, five patients had EH on both sides (Table 5). In contrast, patients with VM did not have EH in the vestibule, with the exception of two patients (Table 6).

MR image of enlarged and normal endolymphatic spaces in the vestibule and in the cochlea (right ears). HYDROPS images of inner ears. The left picture shows significant endolymphatic hydrops (black areas) both in the vestibule and in the cochlea (right ear of patient no. 3 in Table 5). The long arrows indicate vestibular endolymphatic hydrops, and the short arrows indicate cochlear endolymphatic hydrops. The right picture shows a normal endolymphatic space both in the vestibule and in the cochlea (right ear of patient no. 3 in Table 6)

Among the 14 ears of the seven patients with vestibular MD, the number of ears with no, mild and significant hydrops in the vestibule was 0, 3 and 11, respectively. In contrast, among the 14 ears of the seven patients with VM, the number of ears with no, mild and significant hydrops in the vestibule was 11, 1 and 2, respectively. When the three degrees of endolymphatic space size were divided into two groups (no hydrops vs. mild or significant hydrops, and no or mild hydrops vs. significant hydrops), a Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test revealed that the degree and frequency of EH in the vestibule were greater in patients with vestibular MD than they were in patients with VM (P < 0.01).

Among the 14 ears of the seven patients with vestibular MD, the number of ears with no, mild and significant hydrops in the cochlea was 4, 6 and 4, respectively. Among the 14 ears of the seven patients with VM, the number of ears with no, mild and significant hydrops in the cochlea was 5, 9 and 0, respectively. Although there was no significant hydrops in the cochlea of patients with VM patients, a Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test revealed no statistical differences (P > 0.05).

Discussion

In the present study, we explored the endolymphatic space in patients with MD and VM using 3T MRI. Our results indicate that patients with VM seldom have EH in the vestibulum, whereas patients with MD frequently show EH in the vestibulum. In MD, EH can occur in the cochlea, vestibulum or in both structures, as the initial complaints may also comprise hearing loss, vertigo or both [19]; in contrast, VM may show EH in the cochlea. VM and MD are occasionally difficult to discriminate clinically [1–9, 23–25]. It is more difficult to discriminate between vestibular MD and VM because vestibular MD does not have hearing loss, and the determination of the affected and non-affected sides is difficult. The present study revealed that endolymphatic space size in the vestibule was significantly different between patients with vestibular MD and VM, and that MRI can be used to differentiate between these two conditions. The results of our study suggest that the pathophysiological process in vestibular MD occurs in the inner ear, whereas it arises in the vestibular nerve and/or the central nervous system in VM. The presence of EH in the cochlea may depend on the spontaneous variability of EH in the normal population. Many individuals with asymptomatic hydrops have been reported [19]. EH is frequently observed post-mortem in the temporal bone of individuals without ear diseases, especially in the upper turn of the cochlea [26]. MRI in normal controls also revealed that EH in the cochlea may occur, whereas EH in the vestibule is relatively rare (unpublished data). In this respect, EH in the ear resembles asymptomatic glaucoma, which occurs ten times more frequently than symptomatic glaucoma in the general population [27, 28].

Analysis of temporal bone specimens has shown variability in the presence of EH [29]. Patients with MD who did not have EH on histological examination have also been reported, and Salt et al. [30] questioned whether the presence of post-mortem EH is either essential or specific to MD. Conversely, Nakashima et al. [17] and Fiorino et al. [31] used MRI to demonstrate that EH was present in all living patients with definite Ménière’s disease. Kato et al. [32] reported endolymphatic space images in 36 patients with cochlear MD and 28 patients with vestibular MD using 3T MRI after intratympanic or intravenous injection of gadolinium contrast agents. In both of these patient groups, EH in the vestibule was more common than EH in the cochlea, which supports our findings. The authors concluded that patients with possible MD often have EH, but the distribution of EH is different between vestibular MD and cochlear MD, as reported previously [19].

Although functional tests, such as the caloric test, vestibular-evoked myogenic potential (VEMP) and the vestibule–ocular reflex, have been used to differentiate between VM and MD, none of these vestibular tests was able to distinguish these disorders [33–37]. Brantberg et al. [12] found a poor temporal association with vertigo and headache and, therefore, concluded that vertigo can occur without headache in VM and that the diagnostic criteria should be based on pathophysiology and not symptoms. In the present study, MRI discriminated MD from VM, although there may also be comorbidity. This association is complicated because migraine may damage the inner ear, thus causing EH [38].

Moreover, in the present study, the complaints reported by patients with VM and MD overlapped (Fig. 2). During the development of MD, the complaints vary, and the establishment of a diagnosis according to the criteria of the AAOHNS is difficult [11]. Because cochlear MD has no vertigo, cochlear MD does not overlap with VM. However, the discrimination between VM and vestibular MD is especially difficult because of the similarity of clinical symptoms, in particular because headache frequently accompanies MD [39, 40]. Under this obscure situation, our results revealed that endolymphatic space size in the vestibule of patients with VM was different from that in patients with vestibular MD. MRI can help to elucidate the pathophysiology of VM and MD.

Conclusions

The aim of the present work was to provide an insight into the assessment of diagnostic aspects between VM and MD for medical practitioners. MD is a condition that is difficult to define clinically, and the existing AAOHNS classification is unhelpful. VM is an entity that expresses association of headache with vertigo and balance problems. In gadolinium-contrasted MRI, patients with MD showed EH in the vestibulum more frequently than in the cochlea, whereas EH was rare in patients with VM. Inner ear imaging using gadolinium-contrasted MRI was helpful in differentiating these two clinical conditions.

References

Neuhauser H, Leopold M, von Brevern M, Arnold G, Lempert T (2001) The interrelations of migraine, vertigo, and migrainous vertigo. Neurology 56:436–441

Radtke A, Lempert T, Gresty MA, Brookes GB, Bronstein AM, Neuhauser H (2002) Migraine and Ménière’s disease—is there a link? Neurology 59:1700–1704

Furman JM, Marcus DA, Balaban CD (2013) Vestibular migraine: clinical aspects and pathophysiology. Lancet Neurol 12:706–715

Lempert T, Neuhauser H (2009) Epidemiology of vertigo, migraine and vestibular migraine. J Neurol 256:333–338

Neuhauser H, Radtke A, von Brevern M, Feldmann M, Lezius F, Ziese T, Lempert T (2006) Migrainous vertigo—prevalence and impact on quality of life. Neurology 67:1028–1033

Huppert D, Strupp M, Brandt T (2010) Long-term course of Menière’s disease revisited. Acta Otolaryngol 130:644–651

Strupp M, Brandt T (2013) Peripheral vestibular disorders. Curr Opin Neurol 26:81–89

Strupp M, Versino M, Brandt T (2010) Vestibular migraine. Handb Clin Neurol 97:755–771

Brandt T, Strupp M, Dieterich M (2014) Five keys for diagnosing most vertigo, dizziness, and imbalance syndromes: an expert opinion. J Neurol 261:229–231

Neff BA, Staab JP, Eggers SD, Carlson ML, Schmitt WR, Van Abel KM, Worthington DK, Beatty CW, Driscoll CL, Shepard NT (2012) Auditory and vestibular symptoms and chronic subjective dizziness in patients with Ménière’s disease, vestibular migraine, and Ménière’s disease with concomitant vestibular migraine. Otol Neurotol 33:1235–1244

Monsell EM, Balkany TA, Gates GA, Goldenberg RA, Meyerhoff WL, House JW (1995) Committee on hearing and equilibrium guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of therapy in Menière’s disease. American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Foundation, Inc. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 113:181–185

Brantberg K, Trees N, Baloh RW (2005) Migraine-associated vertigo. Acta Otolaryngol 125:276–279

Alford BR (1972) Report of subcommittee on equilibrium and its measurement. Meniere’s disease: criteria for diagnosis and evaluation of therapy for reporting. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 76:1462–1464

Kahmke R, Kaylie D (2012) What are the diagnostic criteria for migraine-associated vertigo? Laryngoscope 122:1885–1886

Radtke A, Neuhauser H, von Brevern M, Hottenrott T, Lempert T (2011) Vestibular migraine, validity of clinical diagnostic criteria. Cephalalgia 31:906–913

Nakashima T, Naganawa S, Sugiura M, Teranishi M, Sone M, Hayashi H, Nakata S, Katayama N, Ishida IM (2007) Visualization of endolymphatic hydrops in patients with Meniere’s disease. Laryngoscope 117:415–420

Nakashima T, Naganawa S, Teranishi M, Tagaya M, Nakata S, Sone M, Otake H, Kato K, Iwata T, Nishio N (2010) Endolymphatic hydrops revealed by intravenous gadolinium injection in patients with Ménière’s disease. Acta Otolaryngol 130:338–343

Naganawa S, Yamazaki M, Kawai H, Bokura K, Sone M, Nakashima T (2010) Visualization of endolymphatic hydrops in Ménière’s disease with single-dose intravenous gadolinium-based contrast media using heavily T-2-weighted 3D-FLAIR. Magn Reson Med Sci 9:237–242

Pyykko I, Nakashima T, Yoshida T, Zou J, Naganawa S (2013) Ménière’s disease: a reappraisal supported by a variable latency of symptoms and the MRI visualisation of endolymphatic hydrops. BMJ Open 3:e001555. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001555

Jerin C, Berman A, Krause E, Ertl-Wagner B, Guerkov R (2014) Ocular vestibular evoked myogenic potential frequency tuning in certain Menière’s disease. Hear Res 310:54–59

Naganawa S, Yamazaki M, Kawai H, Bokura K, Sone M, Nakashima T (2012) Imaging of Ménière’s disease after intravenous administration of single-dose gadodiamide: utility of subtraction images with different inversion time. Magn Reson Med Sci 11:213–219

Nakashima T, Naganawa S, Pyykko I, Gibson WPR, Sone M, Nakata S, Teranishi M (2009) Grading of endolymphatic hydrops using magnetic resonance imaging. Acta Otolaryngol 129:5–8

Best C, Eckhardt-Henn A, Tschan R, Dieterich M (2009) Psychiatric morbidity and comorbidity in different vestibular vertigo syndromes. J Neurol 256:58–65

Radtke A, von Brevern M, Neuhauser H, Hottenrott T, Lempert T (2012) Vestibular migraine: long-term follow-up of clinical symptoms and vestibulo-cochlear findings. Neurology 79:1607–1614

Lempert T, Olesen J, Furman J, Waterston J, Seemungal B, Carey J, Bisdorff A, Versino M, Evers S, Newman-Toker D (2012) Vestibular migraine: diagnostic criteria. J Vestib Res 22:167–172

Foster CA, Breeze RE (2013) Endolymphatic hydrops in Ménière’s disease: cause, consequence, or epiphenomenon? Otol Neurotol 34:1210–1214

Iwase A, Suzuki Y, Araie M, Yamamoto T, Abe H, Shirato S, Kuwayama Y, Mishima HK, Shimizu H, Tomita G, Inoue Y, Kitazawa Y, Tajimi Study Group, Japan Glaucoma Society (2004) The prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma in Japanese: the Tajimi study. Ophthalmology 111:1641–1648

Yamamoto T, Iwase A, Araie M, Suzuki Y, Abe H, Shirato S, Kuwayama Y, Mishima HK, Shimizu H, Tomita G, Inoue Y, Kitazawa Y, Tajimi Study Group, Japan Glaucoma Society (2005) The Tajimi study report 2: prevalence of primary angle closure and secondary glaucoma in a Japanese population. Ophthalmology 112:1661–1669

Merchant SN, Adams JC, Nadol JB (2005) Pathophysiology of Ménière’s syndrome: are symptoms caused by endolymphatic hydrops? Otol Neurotol 26:74–81

Salt AN, Plontke SK (2010) Endolymphatic hydrops: pathophysiology and experimental models. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 43:971–977

Fiorino F, Pizzini FB, Beltramello A, Mattellini B, Barbieri F (2011) Reliability of magnetic resonance imaging performed after intratympanic administration of gadolinium in the identification of endolymphatic hydrops in patients with Ménière’s disease. Otol Neurotol 32:472–477

Kato M, Sugiura M, Shimono M, Yoshida T, Otake H, Kato K, Teranishi M, Sone M, Yamazaki M, Naganawa S, Nakashima T (2013) Endolymphatic hydrops revealed by magnetic resonance imaging in patients with atypical Meniere’s disease. Acta Otolaryngol 133:123–129

Sharon JD, Hullar TE (2014) Motion sensitivity and caloric responsiveness in vestibular migraine and Meniere’s disease. Laryngoscope 124:969–973

Shin JE, Kim C-H, Park HJ (2013) Vestibular abnormality in patients with Meniere’s disease and migrainous vertigo. Acta Otolaryngol 133:154–158

Celebisoy N, Gokcay F, Sirin H, Bicak N (2008) Migrainous vertigo: clinical, oculographic and posturographic findings. Cephalalgia 28:72–77

Baier B, Stieber N, Dieterich M (2009) Vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials in vestibular migraine. J Neurol 256:1447–1454

Geraldine Zuniga M, Janky KL, Schubert MC, Carey JP (2012) Can vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials help differentiate Ménière disease from vestibular migraine? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 146:788–796

Lee H, Lopez I, Ishiyama A, Baloh RW (2000) Can migraine damage the inner ear? Arch Neurol 57:1631–1634

Eklund S (1999) Headache in Meniere’s disease. Auris Nasus Larynx 26:427–433

Murdin L, Davies RA, Bronstein AM (2009) Vertigo as a migraine trigger. Neurology 73:638–642

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan (Kiban B-25293263, Kiban C-25462634 and Yong Scientists B 25861548).

Conflicts of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard

All human studies have been approved by the appropriate ethics committee and have therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at Nagoya University Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nakada, T., Yoshida, T., Suga, K. et al. Endolymphatic space size in patients with vestibular migraine and Ménière’s disease. J Neurol 261, 2079–2084 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-014-7458-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-014-7458-9