Abstract

Previous papers show discordant patterns of monthly and seasonal differences in the frequency of multiple sclerosis relapses. Attacks are more often reported in spring and summer, but there are many variations, mainly as to summer peaks. This paper, an MSBase collaboration substudy, reports multiple series of relapses from 1980 to 2010, comparing ultradecennal trends of seasonal frequency of attacks in different countries. The MSBase international database was searched for relapses in series recording patient histories from 1980 up to 2010. The number of relapses by month was stratified by decade (1981–1990, 1991–2000, 2001–2010). Positive spring versus summer peaks were compared by odds ratios; different series were compared by weighted odds ratio (Peto OR). Decade comparison of the 1990s versus 2000s shows inversion of spring–summer peak (2000s = March; 1990s = July), significant in the whole group (Peto odds ratio = 1.31, CI = 1.10–1.56, p = 0.003) and in Salerno series (OR = 1.97, CI = 1.14–1.40). The global significance persisted also excluding Salerno series (Peto odds ratio = 1.25, CI = 1.04–1.50, p = 0.002). Multicentric data confirm a summer peak of relapses in the 1991–2000 decade, significantly different from the spring peak of 2001–2010. Seasonal frequency of relapses shows long-term variations, so that other factors such as viral epidemics might have more relevance than ultraviolet exposure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Previous papers show, in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), discordant patterns of monthly and seasonal differences in the frequency of relapses. Peaks of attacks are more often reported in spring, also supported by a meta-analysis [1–3], and in summer, up to 2010 [4–6], but there are many variations, mainly as to summer peaks. Other papers show higher frequency in winter [7], or multiple peaks (summer and winter [8], summer and spring [9]), a negative peak in late summer [10], and also only small [11] or no monthly differences [12, 13].

Latitude and climate can account only partly for the differences: summer peaks seem to be reported mainly in warmer countries [3, 6, 9], and more spring or winter attacks in northern countries [1, 3, 7], but there are warm countries with no peaks in summer [10, 11], or summer peaks (such as in North Dakota) [5]. In the Southern Hemisphere the main peak is not in summer but in autumn [13]. Papers report a positive correlation with temperature [2, 8, 13], and a negative correlation with precipitation [14]; others do not find any correlation [12].

The viral hypothesis is the most investigated factor possibly explaining seasonal differences; however, vitamin D, which is supposed to be one of the factors for latitude differences [15–23], is also taken into consideration for the spring peaks of relapses.

In a polycentric study, global data from the MSBase registry [24, 25], showed different findings: a significant seasonal variation in both hemispheres, with a main peak in June, on about 22,000 relapses, confirmed on about 5,000 first events [24], and different spring peaks (April in northern, October in southern countries) with secondary peaks in autumn, on 14,000 relapses [25].

A retrospective observational study using high-frequency serial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), performed in 1991–1993 on 44 cases [26], shows that the peak of T2 MRI activity was in summer (March–August), strongly correlated with higher temperatures.

Recent data published by one of us [27], stratifying in the long term the seasonal frequency, found significant differences between the last two decades, with a spring peak in the 2000s versus a summer peak in the 1990s. A MSBase collaboration substudy, including only series which recorded relapses in different decades, was proposed to confirm these data.

This paper reports the data of this MSBase collaboration substudy, based on multiple series of relapses reported from 1980 to 2010, so as to compare ultradecennal trends of seasonal frequency of attacks in different countries.

Methods

MSBase is an ongoing, longitudinal, strictly observational registry open to all practicing neurologists worldwide. In collaboration with participating physicians, the MSBase registry establishes a unique international database dedicated to sharing, tracking, and evaluating outcomes data in MS [28].

Currently, seven series from six countries are included in the substudy: Argentina (Buenos Aires), Belgium (Brussels), Canada (Montreal), Italy (Chieti), Italy (Salerno), Spain (Madrid), and Turkey (Trabzon).

To minimize selection bias, only patients with complete data were included. Demographic data are presented in Table 1.

Only attacks with a definite onset were considered; dates conventionally used to indicate relapses of unknown onset were excluded: January 1 for all series, June 1 for Spain, June 15 for Italy, Chieti.

Criteria for diagnosis of relapses were: new symptoms or signs lasting at least 24 h; exclusion of pseudorelapses or paroxystic episodes; minimal interval between two attacks of at least 30 days [29].

Austral hemisphere series (Argentina) was registered, seasonally, from July (first month) to June (last).

The number of relapses by month was calculated and stratified by decade (1981–1990, 1991–2000, 2001–2010). Positive spring (March) versus summer (July) peaks were compared by odds ratios and chi-square tests; different series were not cumulated, but compared by weighted odds ratio (Peto).

Results

The total number of relapses by month is summarized in Table 2. The 1970s and 1980s decades show of course a lower number of relapses, because MSBase registries started in the late 1990s, and previous data are anamnestic. So, only the last two decades were compared.

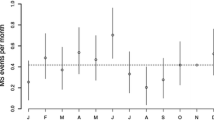

Relapse numbers for 1990 (1991–2000) and 2000 (2001–2010) decades are tabulated in Tables 3 and 4; The same data are shown graphically in Fig. 1. The number of relapses in 1990 has its peak (mode) in July (Fig. 1a); in 2000 the peak is in March (Fig. 1b).

However, the single series show many variations and cannot be simply cumulated, so we calculated and compared spring versus summer peaks, series by series and decade by decade. Statistical comparison between the two last decades is shown in Figs. 2 and 3. Decade comparison of the 1990s versus the 2000s shows inversion of spring–summer peak (March in 2000s, July or August in 1990s), which is significant in the whole group (Peto odds ratio = 1.31, CI = 1.10–1.56, p = 0.003) and in Salerno series (OR 1.97, CI 1.14–1.40) (Fig. 2).

The cumulative significance was confirmed (Peto odds ratio = 1.25, CI = 1.04–1.50, p = 0.002) also in a sensitivity analysis excluding Salerno series, which is the only one showing significant results even alone (Fig. 3).

Discussion

There are no previous multicentric studies comparing different decades; the only paper, to our knowledge, addressing this issue is a single-center study by Iuliano [27].

In the present study we widened the population and geographical areas under study.

Our multiple series confirm the high variability shown in the literature (see “Background”) and can reasonably explain this variability.

Previous papers [1–14] do not seem to show definitive trends for spring or summer peaks, also when classified for year of publication, except, possibly, for some papers published after 2004 and showing multiple and hardly statistically assessable peaks, mainly in spring and summer [8, 10, 11].

There are, however, papers confirming a spring peak published in the 2000s [2, 25], and a summer peak published in the 1990s [4, 5]; in addition, a recently published paper based on MRI serial data collected in 1991–1993 also shows a significant summer peak of MRI activity [26].

There are limitations: as the number of patients and of recorded attacks is, in all series, increasing with time, reliable comparison among different decades was possible only for the last two. It is hardly possible that further addition of patients could allow more comparisons, because recalling old events is increasingly difficult with time.

Another limitation is the impossibility of obtaining old data about climate, epidemics, and environmental variables to study possible correlations, which is even more difficult as they would need to be aggregated as mean decade data.

Anyway, variables such as epidemics or local environment factors may be changing over time; other environmental factors, such as UV exposure or climate, are certainly more stable along the course of a year.

Conclusions

Comparison of series from multiple geographical areas confirms a spring peak of relapses in the 2000–2009 decade, contrary to the 1990–1999 one, where a summer peak is evident. Independently from the year period of peaks, seasonal frequency of relapses might vary in the long term, due to other factors such as viral epidemics or other environmental variables, whose effect could be more evident than climate, ultraviolet exposure, and correlated factors.

References

Jin YP, de Pedro-Cuesta J, Soderstrom M, Link H (1999) Incidence of optic neuritis in Stockholm, Sweden, 1990–1995: II. Time and space patterns. Arch Neurol 56(8):975–980

Salvi F, Bartolomei I, Smolensky MH, Lorusso A, Barbarossa E, Malagoni AM, Zamboni P, Manfredini R (2010) A seasonal periodicity in relapses of multiple sclerosis? A single-center, population-based, preliminary study conducted in Bologna, Italy. BMC Neurol 1(10):105

Jin Y, de Pedro-Cuesta J, Soderstrom M, Stawiarz L, Link H (2000) Seasonal patterns in optic neuritis and multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci 181(1–2):56–64

Bamford CR, Sibley WA, Thies C (1983) Seasonal variation of multiple sclerosis exacerbations in Arizona. Neurology 33(6):697–701

Goodkin DE, Hertsgaard D (1989) Seasonal variation of multiple sclerosis exacerbations in North Dakota. Arch Neurol 46(9):1015–1018

Abella-Corral J, Prieto JM, Dapena-Bolaño D, Iglesias-Gómez S, Noya-García M, Lema M (2005) Seasonal variations in the outbreaks in patients with multiple sclerosis. Rev Neurol 40(7):394–396

Bisgård C (1990) Seasonal variation in disseminated sclerosis. Ugeskr Laeger 152(16):1160–1161

Ogawa G, Mochizuki H, Kanzaki M, Kaida K, Motoyoshi K, Kamakura K (2004) Seasonal variation of multiple sclerosis exacerbations in Japan. Neurol Sci 24(6):417–419

Iuliano G, Napoletano R, Esposito A (2005) Seasonal differences in the frequency of relapse in multiple sclerosis. (article in italian, abstract in english) Riv. It. Neurobiologia II(4):209–212

Tremlett H, van der Mei IA, Pittas F, Blizzard L, Paley G, Mesaros D, Woodbaker R, Nunez M, Dwyer T, Taylor BV, Ponsonby AL (2008) Monthly ambient sunlight, infections and relapse rates in multiple sclerosis. Neuroepidemiology 31(4):271–279 (published online first: 30 October 2008)

Koziol JA, Feng AC (2004) Seasonal variations in exacerbations and MRI parameters in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neuroepidemiology 23(5):217–223

Fonseca AC, Costa J, Cordeiro C, Geraldes R, de Sá J (2009) Influence of climatic factors in the incidence of multiple sclerosis relapses in a Portuguese population. Eur J Neurol 16:537–539. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02528.x (Published online first: Jan 27)

Saaroni H, Sigal A, Lejbkowicz I, Miller A (2010) Mediterranean weather conditions and exacerbations of multiple sclerosis. Neuroepidemiology 35(2):142–151 Epub 2010 Jun 23

O’Reilly MA, O’Reilly PM (1991) Temporal influences on relapses of multiple sclerosis. Eur Neurol 31(6):391–395

Mealy MA, Newsome S, Greenberg BM, Wingerchuk D, Calabresi P, Levy M (2011) Low serum vitamin D levels and recurrent inflammatory spinal cord disease. Arch Neurol Nov 14. [Epub ahead of print]

Simpson S Jr, Taylor B, Blizzard L, Ponsonby AL, Pittas F, Tremlett H, Dwyer T, Gies P, van der Mei I (2010) Higher 25-hydroxyvitamin D is associated with lower relapse risk in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 68(2):193–203

Van der Mei IA, Ponsonby AL, Dwyer T, Blizzard L, Taylor BV, Kilpatrick T, Butzkueven H, McMichael AJ (2007) Vitamin D levels in people with multiple sclerosis and community controls in Tasmania, Australia. J Neurol 254(5):581–590 (published online first: 11 April 2007)

Davis GE Jr, Lowell WE (2006) Solar cycles and their relationship to human disease and adaptability. Med Hypotheses 67(3):447–461 (published online first: 15 May 2006)

Freedman DM, Dosemeci M, Alavanja MC (2000) Mortality from multiple sclerosis and exposure to residential and occupational solar radiation: a case-control study based on death certificates. Occup Environ Med 57(6):418–421

McMichael AJ, Hall AJ (1997) Does immunosuppressive ultraviolet radiation explain the latitude gradient for multiple sclerosis? Epidemiology 8(6):642–645

Hutter CD, Laing P (1996) Multiple sclerosis: sunlight, diet, immunology and aetiology. Med Hypotheses 46(2):67–74

Hutter C (1993) On the causes of multiple sclerosis. Med Hypotheses 41(2):93–96

Lauer K (1994) The risk of multiple sclerosis in the USA in relation to sociogeographic features: a factor-analytic study. J Clin Epidemiol 47(1):43–48

Gray OM, Jolley D, Zwanikken C, Trojano M, Grand-Maison F, Duquette P et al (2009) Temporal variation of onset of relapses in multiple sclerosis: results from the Northern and Southern Hemispheres in the Msbase registry (abstract). Neurology 72(suppl 3):8–27

O. Gray, D. Jolley, K. Gibson, M. Trojano, C. Zwanikken, F. Grand’Maison, P. Duquette, G. Izquierdo, P. et al (2009) Onset of relapses in multiple sclerosis: the effect of seasonal change in both the northern and southern hemisphere (abstract). Multiple Sclerosis 15 (suppl 2): p532, s158

Meier DS, Balashov KE, Healy B, Weiner HL, Guttmann CRG (2010) Seasonal prevalence of MS disease activity. Neurology 75:799–806

Iuliano G (2011) Multiple sclerosis: long time modifications of seasonal differences in the frequency of clinical attacks. Neurol Sci 33(5):999–1003. doi:10.1007/s10072-011-0873-0

Butzkueven H, Boz C, Chapman J et al (2010) MSBase, an international platform dedicated to linking multiple sclerosis researchers—observational plan, 6th edition. The MSBase Foundation Ltd, Parkville

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Edan C et al (2005) Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald criteria”. Ann Neurol 58(6):840–846

Conflicts of interest

Gerardo Iuliano has had travel/accommodation/meeting expenses funded by Bayer Schering, Sanofi Aventis, Merck Serono, Novartis, and Biogen Idec, Cavit Boz, Edgardo Cristiano, and Pierre Duquette declare no conflicts of interest. Alessandra Lugaresi has received honoraria or grants from Bayer Schering, Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, Sanofi Aventis, Novartis, and Teva. Dr. Oreja-Guevara has participated in clinical trials and other research projects promoted by Biogen Idec, GSK, Merck-Serono, Teva, and Novartis. Vincent Van Pesch has received compensation for serving on an advisory board for Biogen Idec (2010–11), travel/accommodations/meeting expenses funded by Bayer Schering, Sanofi Aventis, Merck Serono, Novartis, and Biogen Idec, and honoraria for speaking engagement funded by Biogen Idec (2011).

Ethical standard

All human studies must state that they have been approved by the appropriate ethics committee and have therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Iuliano, G., Boz, C., Cristiano, E. et al. Historical changes of seasonal differences in the frequency of multiple sclerosis clinical attacks: a multicenter study. J Neurol 260, 1258–1262 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-012-6785-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-012-6785-y