Abstract

Background

Asthma is one of the most common chronic conditions. Knowing the longitudinal trends of prevalence is important in developing health service planning and in assessing the impact of the disease. However, there have been no studies that examined current asthma prevalence trends in Korea through the analysis of nationwide surveys.

Methods

Data were acquired from patients aged 20–59 years who participated in the First Korean National Health and Nutritional Examination Surveys (KNHANES), which was conducted in 1998, and in the second year of the Fourth KNHANES, which was conducted in 2008. To estimate the prevalence of asthma with age and gender standardization, we used data from the Population and Housing Census, which was conducted by Statistics Korea in 2005.

Results

The prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma increased from 1998 to 2008 (1998: 0.7 %, 2008: 2.0 %). The prevalence of asthma medication usage also increased from 1998 to 2008 (1998: 0.3 %, 2008: 0.7 %); however, the prevalence of wheezing decreased between 1998 and 2008 (1998: 13.7 %, 2008: 6.3 %). A similar trend was observed after estimating the prevalence of asthma with age and gender standardization. Allergic rhinitis might be the reason for the increased prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma, while the observed decrease in wheezing may be related to the decrease in smoking or the increase in the use of asthma medication.

Conclusions

The present study showed that the prevalence of both self-reported physician-diagnosed asthma and asthma medication usage increased from 1998 to 2008 in Korea, despite a possible changing pattern of diagnosing asthma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Asthma is one of the most common chronic conditions, affecting approximately 300 million people worldwide [1], and it has a negative effect on both individuals and society. It has been reported that the prevalence of asthma has increased in many countries over the last few decades [1, 2]. However, recent studies have reported a diminishing prevalence of asthma, especially in some developed countries [3–5], although conflicting results have also been reported [6, 7].

Knowing the longitudinal trends of the prevalence of asthma is important in health service planning and in assessing the impact of the disease. Because the observed changes in the prevalence of asthma may be partially due to the changing pattern of diagnostic practice [7], it is necessary to apply a consistent methodology when assessing the prevalence of asthma. However, an accurate diagnosis of asthma is challenging because of the absence of a gold standard diagnostic tool. Although an objective method like a spirometry or an airway hyperresponsivness test can be used in diagnosing asthma and for excluding other diseases like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a questionnaire-based self-report of asthma is the most common method for defining asthma in epidemiology studies. A few recent studies have evaluated changes in the prevalence of adult asthma in a region over the study period and used consistent methodologies. Almost all of these studies have been performed in Europe [8–10], with a few studies conducted in Asian countries [11]. Furthermore, there have been no nationwide studies in Asia evaluating the prevalence of asthma.

The Korean National Health and Nutritional Examination Surveys (KNHANES) was a population-based national study of a representative sample of Korea and the survey included data related to asthma. The aim of this study was to analyze the changes in the prevalence of self-reported asthma and the pattern of related factors in adults between 1998 and 2008 using the KNHANES data.

Patients and Methods

Study Population

The data used in this study were acquired from the First Korean National Health and Nutritional Examination Surveys (KNHANES I) in 1998 and from the second year (2008) of the Fourth Korea National Health and Nutritional Examination Surveys (KNHANES IV). The subjects included in this study were aged 20–59 years and answered the questionnaire included in the Health Examination Survey section. The data obtained from the questionnaire were analyzed. Additionally, we used data from the Population and Housing Census conducted by Statistics Korea in 2005 to estimate the prevalence of asthma after age and gender standardization. Although KNHANES IV was based on data from the Population and Housing Census in 2005, KNHANES I was not. Thus, we corrected the prevalence of asthma between 1998 and 2008 with age and gender standardization using data from the Population and Housing Census conducted by Statistics Korea in 2005. We obtained the data about age and gender distribution from the Population and Housing Census conducted by Statistics Korea in 2005 and adjusted the data on age and gender distribution from the KNHANES I and IV data according to the distribution of age and gender from the Population and Housing Census conducted by Statistics Korea in 2005.

KNHANES

KNHANES I was conducted from November 1998 to December 1998 and KNHANES IV was conducted from July 2007 to December 2009. The KNHANES are nationwide surveys conducted by the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The surveys are performed in both urban and rural settings and include the 16 administrative districts. We divided Korea into 219,771 areas in 1998 and 264,198 areas in 2008. A multistage and stratified probability sampling method was used in selected survey units. Among these, a final 200 survey areas were randomly selected by geographic area, place of residence (urban/rural), and residential type (apartment/nonapartment). The sample was weighted to adjust for oversampling, nonresponders, and post-stratification. The surveys comprise a Health Behavior Survey, a Health Interview Survey, a Health Examination Survey, and a Nutritional Survey. Data were obtained by trained interviewers.

Questionnaire for the Asthma Survey

The questionnaire contained questions on physician-diagnosed asthma, wheezing, and the use of asthma medication. We used the following survey questions in this study: “Have you ever been diagnosed with asthma by a doctor?” “Have you had wheezing or whistling in your chest at any time in the last 12 months?” “Are you currently taking any medicine (including inhalers, aerosols or tablets) for asthma?”

Factors Associated with Clinical Characteristics

Demographic information, socioeconomic status, smoking history, allergic rhinitis, and body mass index (BMI) were investigated. Additionally, a survey on allergic rhinitis, a related disease, was conducted. Participants were classified into five BMI groups according to the World Health Organization’s criteria for Asia-Pacific populations [12]: BMI < 18.5, 18.5 ≤ BMI < 23.0, 23.0 ≤ BMI < 25.0, 25.0 ≤ BMI < 30.0, and BMI ≥ 30.0.

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Severance Hospital (IRB number: 4-2011-0207). The need for informed consent was waived by the IRB as this was a retrospective study.

Statistical Analysis

To adjust for unequal probabilities of selection, all estimates were calculated based on sampling weights for sample area, household selection rate, and sample household and response rate of the subjects. The prevalence of self-reported asthma was calculated using the SURVEYFREQ procedure, and other statistical analyses were conducted using SAS ver. 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). A χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze categorical variables. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to assess the factors related to asthma. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

A total of 7,146 subjects in 1998 and 4,980 subjects in 2008 were included in this study. The mean age was 38.3 ± 10.7 years in 1998 and 40.4 ± 10.5 years in 2008. The proportion of women was 52.3 % in 1998 and 56.7 % in 2008. The proportion of current smokers was considerably lower in 2008 (25.7 %) than in 1998 (35.6 %), and was down in all age groups. In 2008, more subjects had a higher level of education than in 1998 (college or higher, 1998: 26.4 %; 2008: 42.5 %). The proportion of subjects who lived in an urban area was higher in 2008 (80.6 %) than in 1998 (70.2 %). The prevalence of allergic rhinitis increased in 2008 compared to that in 1998 (1998: 1.7 %, 2008: 13.6 %).The prevalence of obesity rose between 1998 and 2008 (1998: 2.2 %, 2008: 3.6 %) (Table 1).

Prevalence of Asthma

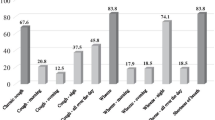

The prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma increased from 1998 to 2008 (1998: 0.7 %, 2008: 2.0 %). This trend was similar in men and women and in all age groups. The prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma was highest in those aged 50–59 years and increased according to age group in 1998 and 2008. The prevalence of asthma medication usage also increased from 1998 to 2008 (1998: 0.3 %, 2008: 0.7 %), and a similar pattern was seen in both men and women. The change in asthma prevalence was greatest in those aged 50–59 years. The prevalence of asthma medication usage was greatest in those aged 50–59 years, which was similar to the prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma. Meanwhile, the prevalence of wheezing decreased between 1998 and 2008 (1998: 13.7 %, 2008: 6.3 %). A similar trend was observed after stratifying by gender and age. Additionally, similar trends were also observed after stratifying by education, smoking, income, and the other factors (data not shown). The prevalence of wheezing was greatest in those aged 50–59 years, followed by the 20–29-year-old age group (Fig. 1).

In addition, we analyzed the prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma, asthma medication usage, and wheezing with gender and age standardization using data from the 2005 Population and Housing Census. The prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma and asthma medication usage increased (physician-diagnosed asthma, 1998: 0.7 %, 2008: 2.1 %; asthma medication, 1998: 0.3 %, 2008: 0.7 %), whereas the prevalence of wheezing decreased (1998: 13.6 %, 2008: 6.3 %). These trends were also observed when study participants were stratified by gender and age. The prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma and asthma medication usage was higher in women than in men, with the exception of the prevalence of asthma medication usage in those aged 40–59 years. The prevalence of wheezing was higher in men than in women among all age groups (Table 2).

Risk Factor Analysis

The risk factor pattern changed between 1998 and 2008. For physician-diagnosed asthma, there was no factor related with asthma in 1998, while allergic rhinitis and residence in a rural area were associated factors in 2008. Current smoking and allergic rhinitis were associated factors for asthma medication usage in 1998. Allergic rhinitis and residence in a rural area were also factors related with current use of asthma medication, which was similar to the risk factors for physician-diagnosed asthma in 2008. Female gender, allergic rhinitis, current smoking, and obesity were common factors related with wheezing in 1998 and in 2008, although female gender and current smoking had a higher impact on wheezing in 2008 than in 1998. Residence in a rural area and low income were associated with wheezing only in 2008 (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study we showed that the prevalence of self-reported physician-diagnosed asthma and asthma medication usage increased from 1998 to 2008, and that the prevalence of wheezing decreased over those 10 years. These trends were similar after stratifying by gender and age and after correcting with gender and age standardization. The risk factors related to physician-diagnosed asthma, asthma medication usage, and wheezing changed between 1998 and 2008.

The study population consisted of adults 20–59 years of age who participated in KNHANES, although persons younger than 20 or older than 59 years old were invited to participate in KNHANES. We excluded the people younger than 20 because we wanted to focus on an adult population, and the population older than 59 years old were excluded to minimize the risk of misclassification of COPD as asthma.

The prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma was relatively low compared to findings in other studies [11, 13]. These previous results found that the prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma was 3.9 % in 2006 in Japan and ranged from 6.05 % (Italy) to 20.09 % (Sweden) in western Europe in 2002–2003. The data based on NHANES III showed that the prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma was 4.5 % and the prevalence of wheezing was 16.4 %. Additionally, we analyzed the prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma and the prevalence of wheezing based on NHANES III data with age standardization using data from the Population and Housing Census of Korea in 2005. The results were as follows: the prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma was 4.6 % and the prevalence of wheezing was 17.3 %. It has been suggested that the prevalence of asthma could vary according to region, country, and national income [1, 14–16]. Nevertheless, the prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma found in our study was lower than of other developing Asian countries (Korea from our study: 1998: 0.69 %, 2008: 2.05 %; Sri Lanka: 2002–2003: 2.60 %; India: 2002–2003: 3.16 %; Philippines: 2002–2003: 7.21 %). One previous Korean study using both questionnaire and bronchial challenge reported that the prevalence of asthma was 3.4 % in 1999 [17]. This suggests that the low prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma in the present study might be related to underdiagnosis of asthma.

The finding that the prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma and asthma medication usage increased and that the prevalence of wheezing decreased is partially consistent with previous studies. Some studies have reported no increase in the incidence of asthma [18–20], while other studies have reported an increase in asthma during the 1990s, with a possible decrease starting in 2000 [5, 6, 21]. These different results may be due to the use of different age groups and different cohorts in one study in evaluating the trends. Meanwhile, an increase in the prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma and a decrease in the prevalence of respiratory symptoms have also been reported in other studies [8–10, 22], and those studies were conducted using a consistent cohort during the study period, and similar age groups were examined in each study. Therefore, the results of increased prevalence of asthma and decreased prevalence of respiratory symptoms were relatively reliable. Thus, our results were also reliable considering that our study was performed using the same region during the study period and similar age groups as in previous studies.

The increase in the prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma and asthma medication usage may have occurred because the proportion of older participants was higher in our study (aging effects) or because the diagnosis and management of asthma increased in the community during the 10-year period (period effects). Aging effects can be excluded as the results were the same after estimating with gender and age standardization. However, period effects cannot be ruled out because accessibility to health care and asthma awareness in the general public have increased, when considering the increased proportion of urban residents and the increase in education level between 1998 and 2008. Since 1980, physicians have been encouraged to diagnose patients with wheezing as having asthma and to manage it [23]. Some repeated cross-sectional studies showed that the increase of reported asthma was faster than the increase in reported symptoms [24–26]. Additional analysis of the rate of use of health care facilities and the trend of diagnosing asthma in the same situations is needed.

The decrease in wheezing may be related to changes in smoking habits. Current smoking was correlated with wheezing in our results, and the proportion of current smokers decreased during the study period, although current smoking showed a greater impact on wheezing in 2008 than in 1998. Previous studies have reported conflicting results in this area. One study in Sweden reported that bronchitic symptoms decreased in parallel with the decrease in current smokers, while shortness of breath and wheezing did not change [9]. In another Swedish study, the prevalence of wheezing decreased along with a decrease in smoking. Better medication could result in decreased severity of asthma, which could be the reason for the decrease in wheezing. This hypothesis was also suggested by Anderson et al. [5], who reported on the prevalence of asthma in the UK.

Allergic rhinitis showed an impact on physician-diagnosed asthma, current asthma medication usage, and wheezing, and its prevalence increased over 10 years. An increase in allergic rhinitis could be the reason for the increase in physician-diagnosed asthma and current asthma medication usage, although rhinitis can be considered a comorbidity of asthma [27, 28]. Future research on the prevalence of allergic sensitization is necessary.

An analysis of the risk factors for asthma showed that rural residence was a risk factor for physician-diagnosed asthma, asthma medication usage, and wheezing only in 2008. Previous data on the relationship between area of residence and asthma are inconsistent. The prevalence of wheezing and asthma are not different across regions in the US [16]. However, these data did not classify the participants according to rural and urban areas. A recent study in Turkey showed that the prevalence of asthma in rural areas was higher than in urban areas, which may be due to increased exposure to biomass smoke and a higher prevalence of childhood respiratory infections [29]. In contrast, there are reports that the farming environment or microbes has a protective effect against allergic disease, a so-called “hygiene hypothesis” [30–35]. The farming environment or microbes might have protected against atopic manifestation in 1998, but might not be protective in urban and rural areas because of changes of environment. However, we could not come to a conclusion about the correlation of rural residence and asthma in 2008 because the environmental factor or the frequency of respiratory infection was not surveyed.

Some reports have shown that obesity is associated with asthma [16, 36]. In our data obesity was associated with wheezing but not with physician-diagnosed asthma or asthma medication usage. This might suggest that there is a relationship between obesity and severe asthma, although the proportion of obese study participants was small. Because obesity is an important health problem and severe asthma is also an important disease status, a more detailed evaluation of the association between obesity and asthma is warranted.

This study has several strengths and limitations. The strengths are that data in our study were obtained from a nationwide study based on a representative sample population in the same area during study periods in which identical questions were used. In addition, we overcame the aging effect by correcting with gender and age standardization using data from the Census. On the other hand, the use of a self-reported questionnaire is a limitation of this study. Without any objective measure, such as a pulmonary function test or an airway hyperresponsivness test, COPD could be misclassified as asthma, although we excluded those older than 59 years old to minimize the proportion of COPD. In addition, we did not survey for other risk factors for asthma, including exposure to biomass smoke, pet ownership, air pollution, and workplace exposure.

In conclusion, the present study showed that the prevalence of self-reported physician-diagnosed asthma and asthma medication usage increased between 1998 and 2008 in Korea despite the possible bias from a changed trend in diagnosing asthma. The prevalence of wheezing decreased during the study period, and this decrease could be related to the decrease in smoking or the increase in asthma medication usage. These observed results may provide a better understanding of the epidemiology of asthma in Korea.

References

Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S, Beasley R (2004) The global burden of asthma: executive summary of the GINA Dissemination Committee report. Allergy 59(5):469–478

Eder W, Ege MJ, von Mutius E (2006) The asthma epidemic. N Engl J Med 355(21):2226–2235

Pearce N, Ait-Khaled N, Beasley R, Mallol J, Keil U, Mitchell E, Robertson C (2007) Worldwide trends in the prevalence of asthma symptoms: phase III of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC). Thorax 62(9):758–766

von Hertzen L, Haahtela T (2005) Signs of reversing trends in prevalence of asthma. Allergy 60(3):283–292

Anderson HR, Gupta R, Strachan DP, Limb ES (2007) 50 years of asthma: UK trends from 1955 to 2004. Thorax 62(1):85–90

Toelle BG, Ng K, Belousova E, Salome CM, Peat JK, Marks GB (2004) Prevalence of asthma and allergy in schoolchildren in Belmont, Australia: three cross sectional surveys over 20 years. BMJ 328(7436):386–387

Magnus P, Jaakkola JJ (1997) Secular trend in the occurrence of asthma among children and young adults: critical appraisal of repeated cross sectional surveys. BMJ 314(7097):1795–1799

Bjerg A, Ekerljung L, Middelveld R, Dahlen SE, Forsberg B, Franklin K, Larsson K, Lotvall J, Olafsdottir IS, Toren K, Lundback B, Janson C (2011) Increased prevalence of symptoms of rhinitis but not of asthma between 1990 and 2008 in Swedish adults: comparisons of the ECRHS and GA(2)LEN surveys. PLoS ONE 6(2):e16082

Ekerljung L, Andersson A, Sundblad BM, Ronmark E, Larsson K, Ahlstedt S, Dahlen SE, Lundback B (2010) Has the increase in the prevalence of asthma and respiratory symptoms reached a plateau in Stockholm, Sweden? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 14(6):764–771

Schaper C, Glaser S, Obst A, Schmidt CO, Volzke H, Felix SB, Ewert R, Koch B (2010) Symptoms and diagnosis of asthma in a general population; longitudinal results from the SHIP database. J Asthma 47(8):860–864

Fukutomi Y, Taniguchi M, Watanabe J, Nakamura H, Komase Y, Ohta K, Akasawa A, Nakagawa T, Miyamoto T, Akiyama K (2011) Time trend in the prevalence of adult asthma in Japan: findings from population-based surveys in Fujieda City in 1985, 1999, and 2006. Allergol Int 60(4):443–448

WHO/IASO/IOTF (2000) The Asia-Pacific perspective: redefining obesity and its treatment. Health Communications Australia, Melbourne

To T, Stanojevic S, Moores G, Gershon AS, Bateman ED, Cruz AA, Boulet LP (2012) Global asthma prevalence in adults: findings from the cross-sectional world health survey. BMC Public Health 12:204

Beasley R, Keil U, von Mutius E, Pearce N, Ait-Khaled N, Anabwani G, Anderson HR, Asher MI, Bjorkstein B, Burr ML, Clayton TO, Crane J, Ellwood P, Lai CKW, Mallol J, Martinez FD, Mitchell EA, Montefort S, Robertson CF, Shah JR, Sibbald B, Stewart AW, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, Williams HC, Childhood ISAA (1998) Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. Lancet 351(9111):1225–1232

Sembajwe G, Cifuentes M, Tak SW, Kriebel D, Gore R, Punnett L (2010) National income, self-reported wheezing and asthma diagnosis from the World Health Survey. Eur Respir J 35(2):279–286

Arif AA, Delclos GL, Lee ES, Tortolero SR, Whitehead LW (2003) Prevalence and risk factors of asthma and wheezing among US adults: an analysis of the NHANES III data. Eur Respir J 21(5):827–833

Sang-hoon Kim JY, Son Sung-Wook, Change Yoon-Suk, Jung Jae-Won, Kim Woon-Keun, Cho Sang-Heon, Min Kyung-Up, Kim You-Young (2001) Prevalence of adult asthma based on questionnaires and methacholine bronchial provocation test in Seoul. J Asthma Allergy Clin Immunol 21:618–627

Ekerljung L, Ronmark E, Larsson K, Sundblad BM, Bjerg A, Ahlstedt S, Dahlen SE, Lundback B (2008) No further increase of incidence of asthma: incidence, remission and relapse of adult asthma in Sweden. Respir Med 102(12):1730–1736

Lundback B, Ronmark E, Jonsson E, Larsson K, Sandstrom T (2001) Incidence of physician-diagnosed asthma in adults—a real incidence or a result of increased awareness? Report from the obstructive lung disease in northern Sweden studies. Respir Med 95(8):685–692

Toren K, Hermansson BA (1999) Incidence rate of adult-onset asthma in relation to age, sex, atopy and smoking: a Swedish population-based study of 15 813 adults. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 3(3):192–197

Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, Lai CK, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, Williams H; ISAAC Phase Three Study Group (2006) Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC phases one and three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet 368(9537):733–743

Chinn S, Jarvis D, Burney P, Luczynska C, Ackermann-Liebrich U, Anto JM, Cerveri I, de Marco R, Gislason T, Heinrich J, Janson C, Kunzli N, Leynaert B, Neukirch F, Schouten J, Sunyer J, Svanes C, Vermeire P, Wjst M (2004) Increase in diagnosed asthma but not in symptoms in the European Community Respiratory Health Survey. Thorax 59(8):646–651

Speight AN, Lee DA, Hey EN (1983) Underdiagnosis and undertreatment of asthma in childhood. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 286(6373):1253–1256

Burney PG, Chinn S, Rona RJ (1990) Has the prevalence of asthma increased in children? Evidence from the national study of health and growth 1973–86. BMJ 300(6735):1306–1310

Ninan TK, Russell G (1992) Respiratory symptoms and atopy in Aberdeen schoolchildren: evidence from two surveys 25 years apart. BMJ 304(6831):873–875

Brogger J, Bakke P, Eide GE, Johansen B, Andersen A, Gulsvik A (2003) Long-term changes in adult asthma prevalence. Eur Respir J 21(3):468–472

Bousquet J, Vignola AM, Demoly P (2003) Links between rhinitis and asthma. Allergy 58(8):691–706

Lundback B (1998) Epidemiology of rhinitis and asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 28(Suppl 2):3–10

Ekici A, Ekici M, Kocyigit P, Karlidag A (2012) Prevalence of self-reported asthma in urban and rural areas of Turkey. J Asthma 49(5):522–526

Riedler J, Eder W, Oberfeld G, Schreuer M (2000) Austrian children living on a farm have less hay fever, asthma and allergic sensitization. Clin Exp Allergy 30(2):194–200

Downs SH, Marks GB, Mitakakis TZ, Leuppi JD, Car NG, Peat JK (2001) Having lived on a farm and protection against allergic diseases in Australia. Clin Exp Allergy 31(4):570–575

Leynaert B, Neukirch C, Jarvis D, Chinn S, Burney P, Neukirch F (2001) Does living on a farm during childhood protect against asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopy in adulthood? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164(10 Pt 1):1829–1834

Von Ehrenstein OS, Von Mutius E, Illi S, Baumann L, Bohm O, von Kries R (2000) Reduced risk of hay fever and asthma among children of farmers. Clin Exp Allergy 30(2):187–193

Riedler J, Braun-Fahrlander C, Eder W, Schreuer M, Waser M, Maisch S, Carr D, Schierl R, Nowak D, von Mutius E (2001) Exposure to farming in early life and development of asthma and allergy: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet 358(9288):1129–1133

Brooks C, Pearce N, Douwes J (2013) The hygiene hypothesis in allergy and asthma: an update. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 13(1):70–77

Shaheen SO, Sterne JAC, Montgomery SM, Azima H (1999) Birth weight, body mass index and asthma in young adults. Thorax 54(5):396–402

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S.Y., Jung, J.Y., Park, M.S. et al. Increased Prevalence of Self-Reported Asthma Among Korean Adults: An Analysis of KNHANES I and IV Data. Lung 191, 281–288 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-013-9453-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-013-9453-9