Abstract

The original cognitive-behavioural (CB) model of bulimia nervosa, which provided the basis for the widely used CB therapy, proposed that specific dysfunctional cognitions and behaviours maintain the disorder. However, amongst treatment completers, only 40–50 % have a full and lasting response. The enhanced CB model (CB-E), upon which the enhanced version of the CB treatment was based, extended the original approach by including four additional maintenance factors. This study evaluated and compared both CB models in a large clinical treatment seeking sample (N = 679), applying both DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria for bulimic-type eating disorders. Application of the DSM-5 criteria reduced the number of cases of DSM-IV bulimic-type eating disorders not otherwise specified to 29.6 %. Structural equation modelling analysis indicated that (a) although both models provided a good fit to the data, the CB-E model accounted for a greater proportion of variance in eating-disordered behaviours than the original one, (b) interpersonal problems, clinical perfectionism and low self-esteem were indirectly associated with dietary restraint through over-evaluation of shape and weight, (c) interpersonal problems and mood intolerance were directly linked to binge eating, whereas restraint only indirectly affected binge eating through mood intolerance, suggesting that factors other than restraint may play a more critical role in the maintenance of binge eating. In terms of strength of the associations, differences across DSM-5 bulimic-type eating disorder diagnostic groups were not observed. The results are discussed with reference to theory and research, including neurobiological findings and recent hypotheses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A considerable treatment literature has been published on bulimia nervosa (BN) [1, 2], which is marked by a chronic and relapse-ridden course, can result into serious medical complications, and is associated with severe comorbid psychopathology and functional impairment [3, 4]. The bulk of this literature has focused on the use of cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), which is widely considered as the treatment of choice for BN [1, 2, 5]. The theory [6] that underpins and guides CBT [7] is primarily concerned with the psychopathological processes that account for the persistence of the disorder. This theory assumes a dysfunctional system for evaluating self-worth [6], whereby self-worth is largely or even exclusively defined in terms of shape and weight and related control [8]. This over-evaluation of shape and weight (OSW) can then lead to dietary restraint, which often includes the adoption of rigid dietary rules about eating and food [6–10]. Due to the psychological and physiological effects of dietary restraint, when these inflexible dietary rules, which are extremely difficult to maintain, are broken, all attempts to control eating are abandoned and a binge occurs [6]. Although several randomised controlled trials have shown that CBT is more effective than a wide range of alternative treatments [1, 2, 5, 11], amongst BN treatment completers, only 40–50 % have a full and lasting response [12–14]. The developers of the original CB theory argued that four additional factors might account for the persistence of dysfunctional cognitions (OSW) and eating-disordered behaviours in some patients that present obstacles for change: (a) interpersonal problems; (b) core low self-esteem; (c) clinical perfectionism; and (d) mood intolerance [12, 13]. Accordingly, they reformulated the original CB theory into an enhanced version by encapsulating these factors that considered being “trans-diagnostic” as well [13]. According to the enhanced CB version (CB-E) [13], the difficulties in establishing and/or maintaining interpersonal relationships may directly precipitate episodes of binge eating, affect all of the other maintenance factors and/or amplify OSW [12, 15]. The pervasive low self-esteem that often persists after recovery [16] is thought to lead to attempts to control shape and weight and similarly contribute to negative affect [13, 17]. Despite adverse consequences, when clinical perfectionism or over-evaluation of striving for and achieving personally demanding standards [18] is present, it might encourage increased striving to achieve unrealistic high standards in the valued domain of shape and weight and foster dietary restraint [13, 18–20]. The final maintenance factor of mood intolerance (i.e. inability to appropriately cope with adverse affective states followed by dysfunctional impulsive behaviours) [13] is believed to directly affect and maintain binge eating [12, 17, 21–24]. The CB-E approach is consistent with research that documented two subtypes of patients with BN and binge eating disorder (BED) based on purely dietary restraint (i.e. approximately 60–70 % of samples) versus dietary-negative affect (i.e. approximately 30–40 % of samples) dimensions [25, 26].

The enhanced CB treatment (CBT-E) approach [7] that derives from the CB-E theory [13] has attracted the interest of clinicians because it is an individual and “modular” form of CBT, in which specific modules may address one or more of the four particular maintaining mechanisms operating in the individual patient’s case [23]. Although recent randomized control trials provided support for its efficacy in any form of eating disorder (ED) [27, 28], this does not necessarily provide evidence for the adequacy of the CB-E theoretical model on which the treatment is based. In fact, there has recently been increased interest on testing some conceptual relationships of the CB-E model in non-clinical adolescent and adult samples [17, 20, 24]. However, it still remains unclear whether the CB-E model adequately represents the conceptual relationships between the four hypothesized maintenance variables, OSW, and disordered behaviours, and how well it accounts for eating-disordered behaviours (i.e. binge eating) amongst bulimic-type ED patients. In fact, the only study with a clinical sample of individuals with DSM-IV—including sub-threshold—anorexia nervosa (AN), and BN investigated only the mutual relationships between each maintenance factor, and their associations with OSW [15]. Moreover, since the CB-E model was developed to expand and improve the original CB model [13], an empirical comparison of the two CB models, in an attempt to evaluate whether the predictive ability of the original model would be improved by the inclusion of the four additional maintenance factors (CB-E model), could potentially have implications for understanding the persistence of bulimic-type EDs and provide indirect support for the utility of the CBT-E [7, 15, 17, 22–24].

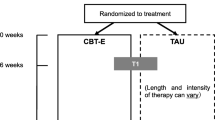

The current study aimed at extending research in this area by testing and comparing the original and CB-E models in a large clinical sample seeking treatment for bulimic-type EDs, which include BN and its variants [bulimic-type ED not otherwise specified (EDNOS), i.e. EDs “clinically significant”, but not meeting full DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for BN, or needing additional study, such as BED] [29]. It was expected that even though both theoretical models (Fig. 1) would provide a good fit to the observed data, the CB-E maintenance model would account for a greater proportion of the variance in dietary restraint and binge eating (i.e. the hallmark behaviour of all bulimic-type EDs) [13, 29]. Evaluating whether the strength of the conceptual relationships of both CB maintenance models is similar or different across diagnostic groups and formally testing the significance of the mediation or indirect effects embedded within the CB models (Fig. 1) in each diagnostic group were additional aims of the study. It is worth of note that prior the completion of the study, the APA Task Force made several changes to ED diagnoses in the DSM-5 [30] in order to reduce the preponderance of the DSM-IV [31] Anorexic and bulimic-type EDNOS category [29, 32] that formed the most common ED among those seeking treatment [33]. Regarding bulimic-type EDNOS, in addition to making BED a formal diagnosis, DSM-5 [30] revised the behavioural criteria (i.e. the threshold for frequency and duration), eliminated the diagnostic subtypes for BN, and changed the EDNOS designation to Other Specified Feeding or ED; Online Resource 1 summarizes the diagnostic criteria for bulimic-type EDs from the fourth to the fifth editions. As a consequence, all cases initially diagnosed as BN and bulimic-type EDNOS using the DSM-IV [31] criteria were re-categorized using the new DSM-5 criteria [30]. All analyses conducted to evaluate our hypothesis (Fig. 1) and potential differences across groups were based on DSM-5 diagnosis of BN, BED, and bulimic-type EDNOSFootnote 1; for simplicity, this last term was used in the current manuscript to refer to bulimic-type diagnoses that fell into the Other Specified Feeding or ED group. Re-categorizing diagnoses also allowed us to evaluate the degree to which the use of DSM-5 criteria [30] decreased the proportion of DSM-IV [31] bulimic-type EDNOS cases. This is also a novel contribution to the current literature given that prior research using the same [34] or a similar [3, 35] procedure focused on community samples rather than on clinical treatment seeking samples.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Participants were drawn from a sample of 893 individuals consecutively referred to, and assessed for treatment of an ED, at five medium-large sized specialized care centres for EDs in Northern, Central, and Southern Italy between February 2011 and June 2013. Though a portion of this data set has already been used to evaluate the role of attachment in DSM-IV EDs [36], there is no overlap between those results and those presented here. In the current study, participants, who met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for BN (n = 275) or bulimic-type EDNOS (n = 404), were included. Exclusion criteria comprised concurrent treatment for eating and weight-related disturbances, severe psychiatric conditions (psychosis) and intellectual disabilities, and insufficient knowledge of Italian. The flowchart of study participants is available in Online Resource 2. DSM-IV [31] ED and lifetime Axis I psychiatric disorder diagnoses were based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I/P) [37]. The ED diagnoses were confirmed by findings from the Eating Disorder Examination-Interview-12.0D (EDE) [38], administered to assess dietary restraint and frequency of binge eating episodes as well (see measures section). At each participating centre, clinicians with experience and training in assessing and treating EDs carried out the diagnostic procedures. Approximately 22 % of the SCID-I/Ps and 20 % of the EDEs conducted were audio-recorded and rated by a blinded clinician to establish inter-rater reliability (κ), which was as follows: between .95 and 1.0 for lifetime and current (i.e. EDs) Axis I disorders; and 1.0 for diagnoses of EDs assessed by the means of EDE. All cases initially diagnosed as BN and bulimic-type EDNOS using the DSM-IV [31] criteria were re-categorized with the new DSM-5 criteria [30] on the basis of information from the interview records [34].Footnote 2

Measures

The baseline routine assessment included the SCID-I/P [37], the EDE 12.0D [38], the SCID–II for assessing Axis II personality disordersFootnote 3 [40], the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI) [41] for assessing depression severity, and measurement of height and weight, from which body mass index (BMI = kg/m2) was calculated. Participants completed also selective scales of standardized instruments (described below) in counterbalanced order in an attempt to offset possible ordering effects. Except for diagnostic items, the EDE 12.0D generates four subscales (i.e. restraint, shape, weight, and eating concern) and provides information regarding the frequency of different forms of overeating, including objective bulimic episodes (OBEs; there is a sense of loss of control over eating and an objectively large amount of food is consumed) over the preceding 28 days [38]. In the current study, the EDE weight concern and shape concern subscales were used to assess OSW, whereas the five items of the EDE restraint subscale provided a measure of dietary restraint,Footnote 4 as recommended [8, 24]. Following scholars’ recommendations [42], the number of OBEs and the Binge Eating Scale [43], that examines behavioural signs, cognitions and feelings during a binge eating episode (i.e. guilt), were used for measuring the frequency and severity of binge eating. Scales of the third version of the Eating Disorder Inventory [44] were used to measure mood intolerance (via the eight items of the emotional dysregulation scale), low self-esteem (via the five items of self-esteem scale), and interpersonal problems (via the interpersonal insecurity scale and the interpersonal alienation scale). Three subscales (i.e. personal standards, concern over mistakes, and doubts about action) of the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale [45] were used to measure clinical perfectionism, as recommended [18]. In our total sample (N = 679), just as in each diagnostic group, the internal reliability estimates of each measure were ≥0.90.

Statistical analyses

After re-categorizing all DSM-IV cases using DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, differences in demographic and clinical variables between diagnostic groups were assessed by means of ANOVA or χ 2 test, as appropriate, followed by post hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction if needed [46]. The appropriate measures of effect size for continuous (partial η 2) or categorical variables (Cramer’ s φ) were calculated. Cut-off conventions for partial η 2 are as follows: small (.01–.09), medium (.10–.24), and large (≥.25) [46]. Cut-off conventions for Cramer’ s φ (with df = 2) are as follows: small (.07–.20), medium (.21–.34), and large (≥.35) [46]. There were no missing data. Latent variable structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to examine both hypothesized CB models, depicted in Fig. 1. It involves estimation of (a) a measurement model and (b) a structural model while accounting for measurement error [39]. The measurement model tests the proposed measurement of study constructs by estimating factor loadings between observed/measured variables and underlying latent variables (Online Resource 3), using confirmatory factor analysis. The structural model retains the components of the measurement model and tests the specified structural relationships between latent variables (i.e. the directional paths; Fig. 1); BMI and depression severity (i.e. BDI score) were covariates in each structural model and specified to predict each of the latent variables [39] in an attempt to reduce their effects on the relationships between the latent variables under investigation [17, 48].Footnote 5 SEM analyses were performed in Mplus version 6.12 [49] with a maximum likelihood approach (as pre-analysis of the data did not reveal any evidence for univariate and multivariate non-normality). Criteria for good measurement and structural model fit were as follows: Comparative Fit Index and Tucker–Lewis Index values ≥.95, standardized root-mean-square residual values ≤.08, and root-mean-square error of approximation values ≤.06 [39, 49]. The Chi-square statistic (χ 2) is also reported. To obtain the most parsimonious and accurate representation of the data, we planned to trim non-significant structural paths and to add paths not originally specified (trimmed/revised model) but that impacted the fit of the model to the data based on the modification indices values (MIs > 5.0) provided by Mplus [39, 49]; the trimmed/revised models were re-examined for good fit, and the initial (hypothesized) and trimmed/revised (nested) models were compared using the Chi-square difference test (Δχ 2) [39]. Because the original and CB-E structural models were not nested models (i.e. hierarchically related to one other in the sense that their parameter sets are subsets of one another), it was not possible to use the Δχ 2 to statistically compare model fit, and therefore, we compared the predictive utility of each CB model by examining the percentage of variance accounted for in dietary restraint and binge eating by each model, as recommended [24, 39].

After testing the proposed measurement and structural CB (i.e. enhanced and original) models in the entire diagnostically mixed sample, participants (N = 679) were grouped according to DSM-5 diagnosis, and multi-group SEM analyses were performed to determine whether the factor loadings and structural paths values differed or were similar across diagnostic groups (i.e. to investigate measurement and structural invariance). Measurement and structural invariance is supported if the strength of the factor loadings and the path estimates is equivalent across groups, respectively. To test for invariance, constrained (i.e. measurement or structural parameters were fixed to be equal for the groups) and unconstrained (i.e. parameters were allowed to vary; nested) models were compared using the Δχ 2 [39]; a non-significant Δχ 2 indicates that model parameters are invariant across DSM-5 diagnostic groups. Finally, as testing the significance of the mediation or indirect effects using bootstrap procedure has been recommended [50], Mplus [49] was specified to (a) create 5,000 bootstrap samples from the data set by random sampling with replacement and (b) generate indirect effects and bias-corrected confidence intervals (95 % CIs) around the indirect effects when analysing the (final) structural models (Fig. 2). If the 95 % CI does not include zero, the indirect effect is statistically significant at .05 [50]. The type of mediation (partial or full) for each DSM-5 diagnostic group was determined by whether or not there was a significant direct path in (final) structural models (Fig. 2). If there was not a significant direct path, then full mediation occurred [39, 49, 50].

Final a enhanced and b original cognitive-behavioural model for the total sample (N = 679) with standardised coefficients. Ellipses represent unobserved latent variables. The observed/measured covariates in the model (i.e. body mass index, depression severity) are estimated and depicted in the supplemental material (Online Resource 4). The values in parentheses from left to right are the path coefficients for the structural model for each DSM-5 diagnostic group in the following order: bulimia nervosa (n = 281), binge eating disorder (n = 195), and bulimic-type eating disorder not otherwise specified (n = 203). * p < 0.05

Results

As can been seen in Table 1, the proportion of bulimic-type EDNOS cases identified based on DSM-IV criteria dropped from 59.5 to 29.9 % (related samples Wilcoxon signed rank test, p < 0.001) when DSM-5 criteria were used. Among the initial 404 DSM-IV bulimic-type EDNOS cases, six were reclassified as BN, and 195 as BED. The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics and differences between DSM-5 bulimic-type ED groups are summarized in Table 2.

When the measurement components of the CB-E (Model 1; Table 3) and original CB (Model 2; Table 3) models were specified and tested, the results indicated that each model provided a good fit to the entire sample data, and all loadings were significant. Furthermore, for each CB model the results of multiple-group analyses revealed factor loadings (i.e. measurement) invariance across the diagnostic groups, as the difference in fit between the constrained and unconstrained models was non-significant (Models 3–6; Table 3). Thus, all latent variables were adequately operationalized (by their respective observed/measured variables) and their meaning did not vary [39] by DSM-5 diagnosis. Online Resource 3 provides the standardized factor loadings for each diagnostic group.

When the structural components of the hypothesized CB-E model (Fig. 1a) were specified, the results indicated that the model provided a good fit to the entire sample data (Model 7; Table 3), and all paths were significant apart from that from dietary restraint to binge eating (Fig. 2a). The hypothesized model did not provide a better fit to the data than the trimmed model, in which the non-significant path was deleted (Model 8; Table 3). Thus, the (most parsimonious) trimmed model was retained [39]. However, from the inspection of the MIs, we noted one un-estimated path with a very large MI value (>5.0) in the trimmed model—the path from dietary restraint to mood intolerance. Therefore, this path was added and the model was re-evaluated. The revised model (Model 9; Table 3) provided a significantly better fit than the trimmed model, and consequently was retained [39]. The significant structural coefficients from this final model are presented in Fig. 2a (for full details regarding covariates see Online Resource 4). The model, controlling for BMI and depression severity (i.e. BDI score), accounted for 53.6 % of the variance in OSW, 49.2 % of the variance in dietary restraint, and 40.1 % of the variance in binge eating. Multiple-group analyses did not reveal structural path differences across the three diagnostic groups in the final structural model (Fig. 2a), as the difference in fit between the constrained and unconstrained modelsFootnote 6 was non-significant (Models 10–11; Table 3). The bootstrap procedure showed that all indirect effects embedded within the final structural model (Fig. 2a) were significant in each diagnostic group (Table 4).

When the structural components of the original CB model (Fig. 1b) were specified, the results indicated that the model provided a good fit to the entire sample data (Model 12; Table 3). However, as shown in Fig. 2b dietary restraint did not predict binge eating, while all other specified paths were statistically significant. The trimmed model, in which the non-significant path was deleted, did not result in decreased model fit (Model 13; Table 3) and thus was retained [39]. This final model, controlling for BMI and depression severity (i.e. BDI score), accounted for 34.6 % of the variance in dietary restraint and 0.4 % of the variance in binge eating (for full details regarding covariates see Online Resource 4). The results of multiple-group analyses did not reveal structural path differences across the three diagnostic groups (Models 14–15; Table 3) in the final structural model (Fig. 2b). The test of the significance of indirect effects was not performed since the lack of the link between restraint and binge eating precludes (Fig. 2b) the existence of mediation [50].Footnote 7

Discussion

The present study aimed at evaluating and comparing in a large sample of individuals with DSM-5 bulimic-type EDs the original and enhanced CB maintenance models upon which the versions of the CBT (original vs. enhanced) are based. We found that the following: (a) interpersonal problems, clinical perfectionism and core low self-esteem were associated with greater OSW, which, in turn, was associated with increased dietary restraint; (b) there was a direct path from interpersonal problems to the other three maintaining factors, as well as from core low self-esteem to mood intolerance; (c) increased clinical perfectionism was associated with increased dietary restraint, whereas increased interpersonal problems and mood intolerance were associated with increased binge eating; (d) dietary restraint only indirectly affected binge eating through mood intolerance; (e) differences across DSM-5 diagnostic groups (i.e. BN, BED, and bulimic-type EDNOS) on the strength of the associations among the CB and CB-E latent variables were not observed (Fig. 2 and Online Resource 4); and (f) although both CB models fitted the data well, the CB-E model fitted the data even better and accounted for a greater proportion of variance in dietary restraint and binge eating than the original model. This last finding supports our hypothesis and suggests that the added hypothesized maintenance variables in the CB model improved its explanatory utility.

The direct path from interpersonal problems to the other three maintaining factors, and the results regarding how each maintenance factor is inter-related with each other, as well as their associations with OSW, all are in accordance with previous findings across individuals with different DSM-IV ED diagnosis, included individuals with threshold and sub-threshold AN [15], and together provide support for the trans-diagnostic nature of the maintenance factors as they pertain to OSW [7, 12, 13, 23]. The finding indicating that clinical perfectionism, interpersonal problems, and core low self-esteem impacted dietary restraint through OSW, highlights the importance of dysfunctional cognitions amongst bulimic-type ED patients and are consistent with CB-E theory and past research [8, 13, 17–20, 48, 51]. Furthermore, the multiple mediating effects of the maintenance factors presented in Table 4 seem to expand on the extant literature indicating that low self-esteem, clinical perfectionism, and mood intolerance are present in bulimic-type ED patients at various levels [15–20, 48, 52], as they contribute to gaining insight into how these factors act in several ways to maintain the OSW and disordered behaviours.

While clinical perfectionism was the only maintaining variable directly linked to dietary restraint, interpersonal problems and mood intolerance were directly linked to binge eating, emphasizing the direct key role that both factors may have in its occurrence [11, 21, 22, 44, 48, 52, 53]. The positive and significant relationships between mood intolerance and binge eating are in accordance with CB-E model, which postulate that binge eating has a regulatory function and occur in an attempt to reduce the negative affective states [13]. However, in the current study, there was no direct relationship between dietary restraint and binge eating. This finding, as well as the evidence that interventions for binge eating that do not focus on reducing OSW and/or dietary restraint (i.e. interpersonal therapy, dialectical-behaviour therapy) decrease binge eating relative to assessment-only control conditions [1, 2, 11, 54, 55], seems incompatible with the theoretical assertion of both CB models, i.e. OSW affects binging indirectly through increasing the likelihood of dietary restraint [6, 13]. Although there is evidence that initial dietary restraint levels predict future onset of binge eating among asymptomatic individuals [24, 56, 57], as in this study, prior research using clinical interviews or ecological momentary assessment failed to support the dietary restraint–binge eating relationship among bulimic-type ED patients [9, 58–60]. Although, the impact of dietary restraint on binge eating deserves further elucidation, the direct paths from interpersonal problems and mood intolerance to binge eating lend some credence to scholars’ suggestion that factors other than restraint may play a more critical role in the maintenance of binge eating among clinical samples [21, 47, 48, 54, 55], and highlight the importance of their inclusion in the CB-E theory, assessment, and target [12, 13, 21, 23, 28]. Moreover, the present study indicated that the dietary restraint–binge eating relationship is fully mediated and explained by mood intolerance. Although this indirect effect was unexpected, it appears consistent with findings from studies indicating that dietary manipulations that transiently deplete tryptophan levels (and consequently 5-HT synthesis in the brain) contribute to dysphoric mood in bulimic-type ED subjects [61, 62], increasing the likelihood that an individual might binge eat to relieve dysphoria [21, 22, 48, 60, 61]. Furthermore, based on the results of neurobiological, molecular-genetic, and brain-imaging studies, Steiger and colleagues [63] postulated that factors affecting 5-HT functional activity may indirectly influence susceptibility to binge eating by heightening affective instability. Abnormal 5-HT status in subjects with bulimic-type EDs may represents the cumulative effects of chronic dietary restraint [64–66], an inherited disposition, the consequence of exposure to intense developmental stressors, and traumatic experiences, and/or their combination [63]. Thus, a better understanding of the underlying serotonergic susceptibilities may explain heterogeneous clinical manifestations within the bulimic-type ED population and help clinicians to select the most appropriate treatment [63]. For instance, people with bulimic-type EDs whose variations in 5-HT status are mainly secondary consequences of dietary attempts may have relatively focal treatment needs (i.e. eating-symptom-focused therapies, such as the original version of CBT). However, different clinical pictures need to be considered. bulimic-type ED patients may benefit from more elaborate forms of interventions, such as the CBT-E [7, 12, 13, 27], in case of more severe 5-HT abnormalities [63], and particularly if they are at least partly linked to affective instability mediated by 5-HT functioning or severe developmental disruptions that can affect both 5-HT functioning and affective instability [63]. Apart from the biological perceptive, cognitive factors may also play a central role in understanding the nature of the association between dietary restraint and binge eating. For instance, according to the abstinence violation effect (AVE) model, the inevitable violation of strict and inflexible dietary rules is thought to activate all-or-none thinking (e.g. perfect restraint vs. complete failure) [67]. This “dichotomous” thinking style, which is common among people who binge eat and addressed within CBT and CBT-E [7, 13], is believed to heighten negative mood and disinhibit attempts to control what one eats [47, 67]. Support for the AVE has been observed among binge-eaters [68, 69]. Furthermore, longitudinal investigations amongst asymptomatic individuals revealed that the emotional distress caused by repeated perceived dietary failures increases mood deflection, which in turn results in increase binge eating [48, 57].

One of several changes to ED diagnoses that the APA Task Force made in DSM-5 [30] to decrease the preponderance of the EDNOS category [29, 32] was the recognition of BED as a formal ED. When the DSM-5 criteria were applied to the current sample, the proportion of bulimic-type EDNOS cases identified based on DSM-IV [31] criteria was reduced by 29.6 %; this reduction was due primarily to the reclassification of individuals into the BED diagnostic category. In sharp contrast to other ED diagnoses, the DSM-5 diagnosis of BED [30] does not include a criterion pertaining to body image, probably because of the belief that shape and weight concerns may simply reflect the (over)weight problems of BED patients [70]. However, research indicated that individuals with BED consistently described themselves as fatter than healthy controls matched for BMI, and their shape and weight concerns decrease as binge eating frequency decreases, even when BMI does not change [70]. The notion that body image concerns might be a clinical feature of BED is further supported by emerging research indicating that: (a) BED patients, as compared to normal-weight, overweight, and obese controls, have significantly greater shape and weight concerns, as well as greater eating-related psychopathology and psychological problems, including greater levels of depression and lower core self-esteem [71]; (b) greater body image concerns are predictors of poorer post-treatment outcomes, regardless of the specific type of treatment for BED [72], [70]; (c) BED patients report greater levels of shape and weight concerns than non-eating-disordered psychiatric controls [71]. The current study also provides evidence that shape and weight concerns are relevant in BED as in the other bulimic-type ED diagnostic groups (Table 2), as the differences across DSM-5 diagnostic groups, were minimal and not significant.Footnote 8 Based on the emerging empirical evidence summarized above and because the absence of a feature reflecting a disturbance in body image for the BED diagnosis casts this ED merely as a behavioural overeating construct, scholars have suggested the routine assessment of shape and weight concerns during clinical practice, as well as the incorporation of body image disturbance in the diagnostic scheme for BED in future DSM revisions, either as an individual criterion or as a diagnostic specifier (i.e. a sub-category within a diagnosis that assists with treatment matching and/or prediction of treatment outcome) [70, 71]. Although much research is still needed, a similar change would be consistent with a ‘‘trans-diagnostic’’ view of EDs [13], in which body image disturbance would be a core diagnostic feature of all EDs.

Apart from body image concerns, the preliminary evidence that all diagnostic groups report comparable scores in all measures used to assess the four maintaining factors (incorporated in the CB-E model) supports the suggestion that intrapersonal problems, core low self-esteem, clinical perfectionism, and mood intolerance are related to all bulimic-type EDs without differences at the diagnostic level [13, 15, 17, 36]. On the other hand, differences between BED and the other bulimic-type ED diagnostic groups were also observed (Table 2). Prior research comparing individuals with provisional DSM-IV BED to either DSM-IV BN purging or non-purging subtypes found significant differences in both current (age, BMI, and dietary restraint at the time of the assessment) and age-historical variables (age of onset) [73–75]. The same pattern was observed in this study using DSM-5 criteria, although the magnitude of the differences was less prominent, and the mean of some of the variables measured at the time of the assessment is higher (i.e. dietary restraint), or lower (i.e. BMI) that one might generally expect for the BED group [73]. Nevertheless, the variability of both current and age-historical variables within BED population is well documented [73, 74], and mean values of both dietary restraint and BMI for BED cases are quite close to those observed in other clinical studies [76, 77], [73]. Since the mean age of our BED participants at the time of assessment is consistent with that reported in several Italian studies [76, 78], but lower than that of American studies (ranging from 38 to 48 years) [73], the possibility that Italians with BED are less tolerant of their overweight condition [78, 79] and thus seek treatment more often than their US counterparts should not be ruled out. However, future studies are needed to corroborate this hypothesis.

To our knowledge, this was the first study evaluating the impact of DSM-5 diagnostic criteria in a large treatment seeking sample for bulimic-type EDs, examining and comparing both the original and the enhanced CB models and, at the same time, testing the measurement and structural invariance and the significance of their proposed indirect effects. There are, however, a number of limitations that must be considered. First, despite the sophisticated data analytic procedures used in the present study, the findings need to be interpreted with caution, as, the cross-sectional nature of our data precludes any firm conclusions about the sequence of model variables and does not allow examination of causal relationships and feedback maintenance loops within the model (i.e. if binge eating encourages dietary restraint) [57, 80]. Empirical testing of these feedback loops would need an enhanced experimental and longitudinal design [39, 57, 81]. Second, although the inclusion of semi-structured interviews would reduce social desirability, the use of self-report measures of some constructs of interest does open results up to these known biases; thus, replication with other methods of data collection (e.g. ecological momentary assessment) would be beneficial. Finally, as noted, we just re-categorized bulimic-type EDNOS cases previously diagnosed under DSM-IV criteria. Although the same or a similar procedure had been performed by previous research [3, 34, 35], it should be noted that participants were not interviewed again and we only relied on notes made during the previous clinical interviews [37, 38]. Overall, the results suggest that the four added hypothesized maintenance variables in the CB model improved its explanatory utility amongst bulimic-type ED patients. Assessment and target of the additional maintenance factors proposed by the CB-E theory may result in improved treatment outcomes amongst patients with bulimic-type EDs who, along with the specific dysfunctional cognitions and behaviours, show significant clinical perfectionism, core low self-esteem, interpersonal problems, and mood intolerance.

Notes

It is should be noted that, although both CB models posit that binge eating may encourage in some individuals compensatory behaviours aimed at counteracting the effects of binge eating on weight [6, 13] for details, in the current manuscript we focused on binge eating and did not incorporate compensatory behaviours neither in the form of purging nor in the form of non-purging for three main reasons: (1) the scheme distinguishing purging and non-purging BN subtypes has been eliminated from DSM-5 (Online Resource 1); (2) the DSM-5 BN and BED diagnoses are distinguished by the presence versus absence of recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviours (Online Resource 1); and (3) the necessary prerequisite of the advanced statistical procedure (see “Statistical Analyses”) used for evaluating if the strength of the conceptual relationships of both CB maintenance models (Fig. 1) is similar or different across DSM-5 BN, BED, and bulimic-type EDNOS (that includes also sub-threshold BED cases) is that the model under investigation should contain the same number of latent variables, each of which includes the same number of measured/observed variables for all groups of interest [39].

Data were analysed first by research clinicians and subsequently by the principal investigator (AD) of the project (κ = 1.0).

Approximately 20 % of the SCID-II conducted were audio-recorded and rated by a blinded clinician to establish inter-rater reliability (κ = .99).

The concept of restraint has been operationalized in various ways, frequently distinguishing the components of dietary restriction (concrete efforts to achieve a desired weight by effecting a negative energy balance between caloric intake and expenditure) versus dietary restraint (the intent to diet and attempts to follow dietary rules or control intake, regardless as to whether or not such attempts are successful) [47]. The subscale used here, coherently with the underpinnings of both CB models [6, 13], assesses dietary restraint, and it should not be considered as a valid measure of actual caloric consumption [47].

In our SEM analyses, we did not control for any other socio-demographic and clinical characteristics (i.e. age, age of onset, presence/absence of comorbidity) though evaluated and reported in this manuscript, since preliminary analyses indicated that they were unrelated to scales/subscales used to specify our latent variables.

The results did not change when both CB models were tested separately in each DSM-5 bulimic-type ED diagnostic group. For fit of the measurement and structural (original and enhanced) CB models, see Online Resource 5.

The significant group differences associated with body image concerns persisted even after adjusting for significant group differences in BMI, age, and depression levels; these are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Hay P (2013) A systematic review of evidence for psychological treatments in eating disorders: 2005–2012. Int J Eat Disord 46:462–469

Wilson TG, Grilo CM, Vitousek KM (2007) Psychological treatment of eating disorders. Am Psychol 62:199–216

Stice E, Marti C, Rohde P (2013) Prevalence, incidence, impairment and course of the proposed DSM-5 eating disorder diagnoses in an 8-year prospective community study of young women. J Abnorm Psychol 22:445–457

Keel PK (2010) Epidemiology and course of eating disorders. In: Agras WS (ed) The Oxford handbook of eating disorders, 1st edn. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 25–34

Wilson GT, Shafran R (2005) Eating disorders guidelines from NICE. Lancet 365:79–81

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Cooper PJ (1986) The clinical features and maintenance of bulimia nervosa. In: Brownell KD, Foreyt JD (eds) Handbook of eating disorders: physiology, psychology and treatment of obesity, anorexia and bulimia, 1st edn. Basic Books, New York, pp 389–404

Fairburn CG (2008) Cognitive behaviour therapy and eating disorders. Guildford Press, New York

Blechert J, Ansorge U, Beckmann S, Tuschen-Caffier B (2011) The undue influence of shape and weight on self-evaluation in anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and restrained eaters: a combined ERP and behavioral study. Psychol Med 41:185–194

Lampard AM, Byrne SM, McLean N, Fursland A (2011) An evaluation of the enhanced cognitive-behavioural model of bulimia nervosa. Behav Res Ther 49:529–535

Williamson DA, White MA, York-Crowe E, Stewart TM (2004) Cognitive-behavioural theories of eating disorders. Behav Modif 28:711–718

Agras WS, Walsh T, Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, Kraemer HC (2000) A multicenter comparison of cognitive-behavioural therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57:459–466

Cooper Z, Fairburn CG (2011) The evolution of “Enhanced” cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: learning from treatment nonresponse. Cognit Behav Pract 18:394–402

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R (2003) Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a transdiagnostic theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther 41:509–528

Steinhausen H, Weber S (2009) The outcome of bulimia nervosa: findings from one-quarter century of research. Am J Psychiatry 166:1331–1341

Tasca GA, Presniak MD, Demidenko N, Balfour L, Krysanski V, Trinneer A, Bissada H (2011) Testing a maintenance model for eating disorders in a sample seeking treatment at a tertiary care center: a structural equation modeling approach. Compr Psychiatry 52:678–687

Daley KA, Jimerson DC, Heatherton TF, Metzger ED, Wolfe BE (2008) State self esteem ratings in women with bulimia nervosa and bulimia nervosa in remission. Int J Eat Disord 41:159–163

Dakanalis A, Timko CA, Riva G, Madeddu F, Clerici M, Zanetti MA (2014) A comprehensive examination of the transdiagnostic cognitive behavioral model of eating disorders in males. Eat Behav 15(1):63–67

Shafran R, Cooper Z, Fairburn CG (2002) Clinical perfectionism: a cognitive-behavioural analysis. Behav Res Ther 40:773–791

Lampard AM, Tasca GA, Balfour L, Bissada H (2013) An evaluation of the transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioural model of eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev 21:99–107

Hoiles KJ, Egan SJ, Kane RT (2012) The validity of the transdiagnostic cognitive behavioural model of eating disorders in predicting dietary restraint. Eat Behav 13:123–126

Goldschmidt AB, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Lavender JM, Peterson CB, Crow SJ, Cao L, Mitchell JE (2014) Ecological momentary assessment of stressful events and negative affect in bulimia nervosa. J Consult Clin Psychol 82:30–39

Hilbert A, Tuschen-Caffier B (2007) Maintenance of binge eating through negative mood: a naturalistic comparison of binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 40:521–530

Fursland A, Byrne S, Watson H, La Puma M, Allen K, Byrne S (2012) Enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy: a single treatment for all eating disorders. J Couns Dev 90:319–329

Allen KL, Byrne SM, McLean NJ (2012) The dual-pathway and cognitive-behavioural models of binge eating: prospective evaluation and comparison. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 21:51–62

Stice E, Fairburn CG (2003) Dietary and dietary-depressive subtypes of bulimia nervosa show differential symptom presentation, social impairment, comorbidity, and course of illness. J Consult Clin Psychol 71:1090–1094

Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT (2001) Subtyping binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 69:1066–1072

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, O’Connor ME, Bohn K, Hawker DM, Wales JA, Palmer RL (2009) Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioural therapy for patients with eating disorders: a two-site trial with 60-week follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 166:311–319

Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB, Crosby RD, Smith TL, Klein MH, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ (2013) A randomized controlled comparison of integrative cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT) and enhanced cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT-E) for bulimia nervosa. Psychol Med 44(3):543–553

Mond JM (2013) Classification of bulimic-type eating disorders: from DSM-IV to DSM-5. J Eat Disord. doi:10.1186/2050-2974-1-33

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington

Walsh BT (2009) Report of the DSM-5 eating disorders work group. American Psychiatric Association DSM-5, Washington

Fairburn C, Bohn K (2005) Eating disorder NOS (EDNOS): an example of the troublesome “not otherwise specified” (NOS) category in DSM-IV. Behav Res Ther 43:691–701

Machado PPP, Goncalves S, Hoek HW (2013) DSM-5 reduces the proportion of EDNOS cases: evidence from community samples. Int J Eat Disord 46:60–65

Keel PK, Brown TA, Holm-Denoma J, Bodell LP (2011) Comparison of DSM–IV versus proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for eating disorders: reduction of eating disorder not otherwise specified and validity. Int J Eat Disord 44:553–560

Dakanalis A, Timko CA, Zanetti MA, Rinaldi L, Prunas A, Carrà G, Riva G, Clerici M (2014) Attachment insecurities, maladaptive perfectionism, and eating disorder symptoms: a latent mediated and moderated structural equation modeling analysis across diagnostic groups. Psychiatry Res 215:176–184

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW (1996) Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0). New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department, NewYork

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z (1993) The eating disorder examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT (eds) Binge eating: nature, assessment, and treatment, 1st edn. Guilford Press, New York, pp 317–360

Byrne B (2011) Structural equation modeling with Mplus basic concepts. Application and Programming, Routledge

First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Benjamin LS (1997) Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). American Psychiatric Press Inc, Washington

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK (1996) Beck depression inventory second edition manual. The Psychological Corporation Harcourt Brace & Company, Texas

Celio AA, Wilfley DE, Crow SJ, Mitchell J, Walsh BT (2004) A comparison of the binge eating scale, questionnaire for eating and weight patterns-revised, and eating disorder examination questionnaire with instructions with the eating disorder examination in the assessment of binge eating disorder and its symptoms. Int J Eat Disord 36:434–444

Gormally J, Black S, Daston S, Rardin D (1982) The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict Behav 7:47–55

Garner DM (2004) Eating disorder inventory-3 professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Odessa

Frost RO, Marten P, Lahart C, Rosenblate R (1990) The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognit Ther Res 14:449–468

Reid HM (2014) Introduction to statistics: fundamental concepts and procedures of data analysis. Sage Publications, London

Stice E, Presnell K (2010) Dieting and the eating disorders. In: Agras WS (ed) The Oxford handbook of eating disorders, 1st edn. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 148–179

Stice E (2002) Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology. A meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 128:825–848

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998) Mplus User’s Guide, 6th edn. Muthén and Muthén, Los Angeles

MacKinnon DP (2011) Integrating mediators and moderators in research design. Res Soc Work Pract 21:675–681

Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Joiner T, Peterson CB, Bardone-Cone A, Klein M, Crow SJ, Mitchell JE, Le Grange D, Steiger H, Kolden G, Johnson F, Vrshek S (2005) Personality subtyping and bulimia nervosa: psychopathological and genetic correlates. Psychol Med 35:649–657

Harrison A, Sullivan S, Tchanturia K, Treasure J (2010) Emotional functioning in eating disorders: attentional bias, emotion recognition and emotion regulation. Psychol Med 40:1887–1897

Hopwood CJ, Clarke AN, Perez M (2007) Pathoplasticity of bulimic features and interpersonal problems. Int J Eat Disord 40:652–658

Burton E, Stice E (2006) Evaluation of a healthy-weight treatment program for bulimia nervosa: a preliminary randomized trial. Behav Res Ther 44:1727–1738

Masson PC, von Ranson KM, Wallace LM, Safer DL (2013) A randomized wait-list controlled pilot study of dialectical behaviour therapy guided self-help for binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther 51(11):723–728

Stice E, Marti C, Durant S (2011) Risk factors for onset of eating disorders: evidence of multiple risk pathways from an 8-year prospective study. Behav Res Ther 49:622–627

Dakanalis A, Timko CA, Carrà G, Clerici M, Zanetti MA, Riva G, Caccialanza R (2014) Testing the original and the extended dual-pathway model of lack of control over eating in adolescent girls. A two-year longitudinal study. Appetite 82:180–193

Fairburn CG, Stice E, Cooper Z, Doll HA, Norman PA, O’Connor ME (2003) Understanding persistence in bulimia nervosa: a 5-year naturalistic study. J Consult Clin Psychol 71:103–109

Lowe MR, Thomas J, Safer DL, Butryn ML (2007) The relationship of weight suppression and dietary restraint to binge eating in bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 40:640–644

Waters A, Hill A, Waller G (2001) Bulimics’ responses to food cravings: is binge eating a product of hunger or emotional state? Behav Res Ther 39:877–886

Bruce KR, Steiger H, Young SN, Ng Ying Kin NMK, Israel M, Le´vesque M (2009) Impact of acute tryptophan depletion on mood and eating related urges in bulimic and nonbulimic women. J Psychiatry Neurosci 34:376–382

Kaye WH, Gendall KA, Fernstrom MH, Fernstrom JD, Mc-Conaha CW, Weltzin TE (2000) Effects of acute tryptophan depletion on mood in bulimia nervosa. Biol Psychiatry 47:151–157

Steiger H, Bruce KR, Groleau P (2011) Neural circuits, neurotransmitters, and behavior serotonin and temperament in bulimic syndromes. In: Adan RAH, Kaye WH (eds) Behavioral neurobiology of eating disorders, 1st edn. Springer, Berlin, pp 126–138

Anderson M, Parry-Billings M, Newsholme EA, Fairburn CG, Cowen PJ (1990) Dieting reduces plasma tryptophan and alters brain 5-HT function in women. Psychol Med 20:785–791

Ehrlich S, Franke L, Scherag S, Burghardt R, Schott R, Schneider N, Brockhaus S, Hein J, Uebelhack R, Lehmkuhl U (2010) The 5-HTTLPR polymorphism, platelet serotonin transporteractivity and platelet serotonin content in underweight and weight-recovered females with anorexia nervosa. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 260:483–490

Steiger H, Gauvin L, Engelberg MJ, Ying NMK, Israel M, Wonderlich SA, Richardson J (2005) Mood- and restraint-based antecedents to binge episodes in bulimia nervosa: possible influences of the serotonin system. Psychol Med 35:1553–1562

Marlatt GA, Gordon JR (1985) Relapse prevention: maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. Guilford Press, New York

Johnson WG, Schlundt DG, Barclay DR, Carr-Nangle RE, Engler LB (1995) A naturalistic functional analysis of binge eating. Behav Ther 26:101–118

Stein RI, Kenardy J, Wiseman CV, Dounchis JZ, Arnow BA, Wilfley DE (2007) What’s driving the binge in binge eating disorder?: a prospective examination of precursors and consequences. Int J Eat Disord 40(3):195–203

Hilbert A, Hartmann AS (2013) Body Image disturbance. In: Alexander J, Goldschmidt AB, Le Grange D (eds) A clinician’s guide to binge eating disorder, 1st edn. Routledge, New York, pp 78–90

Hrabosky JI (2011) Body image and binge-eating disorder. In: Cash TF, Smolak L (eds) Body image: a handbook of science, practice, and prevention, 2nd edn. Guilford Press, New York, pp 296–304

Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Crosby RD (2012) Predictors and moderators of response to cognitive behavioural therapy and medication for the treatment of binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 80:897–906

Mitchell JE, Devlin MJ, de Zwaan M, Crow SJ, Peterson CB (2008) Binge-eating disorder: clinical foundations and treatment. Guilford Press, New York

Munsch S, Dubi K (2005) Binge eating disorder: specific and common features. A comprehensive overview. In: Munsch S, Beglinger C (eds) Obesity and binge eating disorder, 1st edn. Karger, Basel, pp 197–216

van Hoeken D, Veling W, Sinke S, Mitchell JE, Hoek HW (2009) The validity and utility of subtyping bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 42:595–602

Santonastaso P, Ferraro S, Favaro A (1999) Differences between binge eating disorder and nonpurging bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 25:215–218

Ekeroth K, Clinton D, Norring C, Birgegård A (2013) Clinical characteristics and distinctiveness of DSM-5 eating disorder diagnoses: findings from a large naturalistic clinical database. J Eat Disord. doi:10.1186/2050-2974-1-31

Clerici M, Dakanalis A (2014) Binge eating and binge eating disorder in Italy: overview. In: Fairburn CG (ed) Overcoming binge eating-second edition: the proven program to learn why you binge and how you can stop, 2nd edn. Raffaelo Cortina Editore, Milan, pp 1–5

Dakanalis A, Zanetti MA, Clerici M, Madeddu F, Riva G, Caccialanza R (2013) Italian version of the Dutch eating behavior questionnaire. Psychometric properties and measurement invariance across sex, BMI-status and age. Appetite 71:187–195

Dakanalis A, Carrà G, Clerici M, Riva G (2014) Efforts to make clearer the relationship between body dissatisfaction and binge eating. Eat Weight Disord. doi:10.1007/s40519-014-0152-1

Dakanalis A, Carrà G, Calogero R, Fida R, Clerici M, Zanetti MA, Riva G (2014) The developmental effects of media-ideal internalization and self-objectification processes on adolescents’ negative body-feelings, dietary restraint, and binge eating. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. doi:10.1007/s00787-014-0649-1

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the psychiatric staff of all Italian specialized care centres (Online Resource 2) for their help in the acquisition of data. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

All participants provided written informed consent. The study was performed in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008, and the study protocol was approved by the ethics review board of each local institution and of the co-ordinating body of the project (University of Pavia).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dakanalis, A., Carrà, G., Calogero, R. et al. Testing the cognitive-behavioural maintenance models across DSM-5 bulimic-type eating disorder diagnostic groups: a multi-centre study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 265, 663–676 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-014-0560-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-014-0560-2